Table of Contents

Chapter 7

Congruence of Triangles

7.1 Introduction

You are now ready to learn a very important geometrical idea, Congruence. In particular, you will study a lot about congruence of triangles.

To understand what congruence is, we turn to some activities.

Do This

Take two stamps (Fig 7.1) of same denomination. Place one stamp over the other. What do you observe?

One stamp covers the other completely and exactly. This means that the two stamps are of the same shape and same size. Such objects are said to be congruent. The two stamps used by you are congruent to one another. Congruent objects are exact copies of one another.

Can you, now, say if the following objects are congruent or not?

1. Shaving blades of the same company [Fig 7.2 (i)].

2. Sheets of the same letter-pad [Fig 7.2 (ii)]. 3. Biscuits in the same packet [Fig 7.2 (iii)].

4. Toys made of the same mould. [Fig 7.2(iv)]

(i)

The relation of two objects being congruent is called congruence. For the present, we will deal with plane figures only, although congruence is a general idea applicable to three-dimensional shapes also. We will try to learn a precise meaning of the congruence of plane figures already known.

7.2 Congruence of Plane Figures

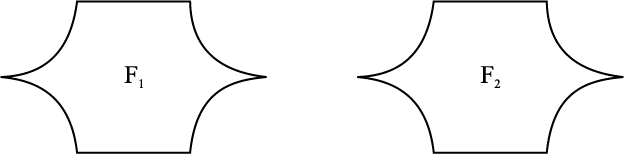

Look at the two figures given here (Fig 7.3). Are they congruent?

(i) (ii)

Fig 7.3

You can use the method of superposition. Take a trace-copy of one of them and place it over the other. If the figures cover each other completely, they are congruent. Alternatively, you may cut out one of them and place it over the other. Beware! You are not allowed to bend, twist or stretch the figure that is cut out (or traced out).

In Fig 7.3, if figure F1 is congruent to figure F2 , we write F1 ≅ F2.

7.3 Congruence Among Line Segments

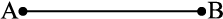

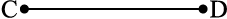

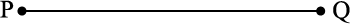

When are two line segments congruent? Observe the two pairs of line segments given here (Fig 7.4).

(ii)

Fig 7.4

Use the ‘trace-copy’ superposition method for the pair of line segments in [Fig 7.4(i)]. Copy  and place it on

and place it on  . You find that

. You find that  covers

covers  , with C on A and D on B. Hence, the line segments are congruent. We write

, with C on A and D on B. Hence, the line segments are congruent. We write  .

.

Repeat this activity for the pair of line segments in [Fig 7.4(ii)]. What do you find? They are not congruent. How do you know it? It is because the line segments do not coincide when placed one over other.

You should have by now noticed that the pair of line segments in [Fig 7.4(i)] matched with each other because they had same length; and this was not the case in [Fig 7.4(ii)].

If two line segments have the same (i.e., equal) length, they are congruent. Also, if two line segments are congruent, they have the same length.

In view of the above fact, when two line segments are congruent, we sometimes just say that the line segments are equal; and we also write AB = CD. (What we actually mean is  ≅

≅  ).

).

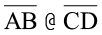

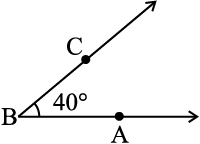

7.4 Congruence of Angles

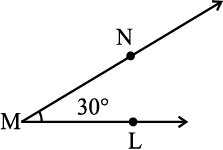

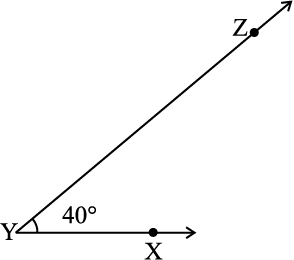

Look at the four angles given here (Fig 7.5).

(iv)

Fig 7.5

Make a trace-copy of ∠PQR. Try to superpose it on ∠ABC. For this, first place

Q on B and  along

along  . Where does

. Where does  fall? It falls on

fall? It falls on .

.

Thus, ∠PQR matches exactly with ∠ABC.

That is, ∠ABC and ∠PQR are congruent.

(Note that the measurement of these two congruent angles are same).

We write ∠ABC ≅ ∠PQR (i)

or m∠ABC = m ∠PQR (In this case, measure is 40°).

Now, you take a trace-copy of ∠LMN. Try to superpose it on ∠ABC. Place M on B and  along

along  . Does

. Does  fall on

fall on  ? No, in this case it does not happen. You find that ∠ABC and ∠LMN do not cover each other exactly. So, they are not congruent.

? No, in this case it does not happen. You find that ∠ABC and ∠LMN do not cover each other exactly. So, they are not congruent.

(Note that, in this case, the measures of ∠ABC and ∠LMN are not equal).

What about angles ∠XYZ and ∠ABC? The rays and

and  , respectively appear [in Fig 7.5 (iv)] to be longer than

, respectively appear [in Fig 7.5 (iv)] to be longer than  and

and  . You may, hence, think that ∠ABC is ‘smaller’ than ∠XYZ. But remember that the rays in the figure only indicate the direction and not any length. On superposition, you will find that these two angles are also congruent.

. You may, hence, think that ∠ABC is ‘smaller’ than ∠XYZ. But remember that the rays in the figure only indicate the direction and not any length. On superposition, you will find that these two angles are also congruent.

We write ∠ABC ≅ ∠XYZ (ii)

or m∠ABC = m∠XYZ

In view of (i) and (ii), we may even write

∠ABC ≅ ∠PQR ≅ ∠XYZ

If two angles have the same measure, they are congruent. Also, if two angles are congruent, their measures are same.

As in the case of line segments, congruency of angles entirely depends on the equality of their measures. So, to say that two angles are congruent, we sometimes just say that the angles are equal; and we write

∠ABC = ∠PQR (to mean ∠ABC ≅ ∠PQR).

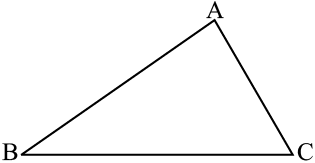

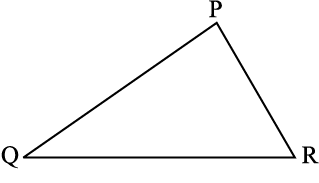

7.5 Congruence of Triangles

We saw that two line segments are congruent where one of them, is just a copy of the other. Similarly, two angles are congruent if one of them is a copy of the other. We extend this idea to triangles.

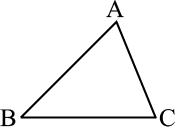

Two triangles are congruent if they are copies of each other and when superposed, they cover each other exactly.

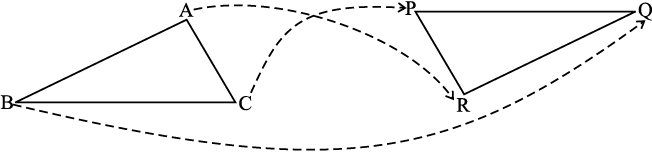

(ii)

Fig 7.6

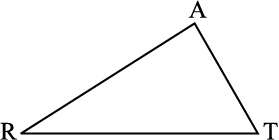

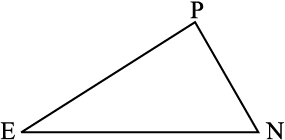

∆ABC and ∆PQR have the same size and shape. They are congruent. So, we would express this as

∆ABC ≅ ∆PQR

This means that, when you place ∆PQR on ∆ABC, P falls on A, Q falls on B and R falls on C, also  falls along

falls along  ,

,  falls along

falls along  and

and  falls along

falls along  . If, under a given correspondence, two triangles are congruent, then their corresponding parts (i.e., angles and sides) that match one another are equal. Thus, in these two congruent triangles, we have:

. If, under a given correspondence, two triangles are congruent, then their corresponding parts (i.e., angles and sides) that match one another are equal. Thus, in these two congruent triangles, we have:

Corresponding vertices : A and P, B and Q, C and R.

Corresponding sides :  and

and  ,

,  and

and  ,

,  and

and  .

.

Corresponding angles : ∠A and ∠P, ∠B and ∠Q, ∠C and ∠R.

If you place ∆PQR on ∆ABC such that P falls on B, then, should the other vertices also correspond suitably? It need not happen! Take trace, copies of the triangles and try to find out.

This shows that while talking about congruence of triangles, not only the measures of angles and lengths of sides matter, but also the matching of vertices. In the above case, the correspondence is

A ↔ P, B ↔ Q, C ↔ R

We may write this as ABC ↔ PQR

Example 1 ∆ABC and ∆PQR are congruent under the correspondence:

ABC ↔ RQP

Write the parts of ∆ABC that correspond to

(i) (ii) ∠Q (iii)

Solution For better understanding of the correspondence, let us use a diagram (Fig 7.7).

The correspondence is ABC ↔ RQP. This means

A ↔ R ; B ↔ Q; and C ↔ P.

So, (i)  ↔

↔  (ii) ∠Q ↔ ∠B and (iii)

(ii) ∠Q ↔ ∠B and (iii)  ↔

↔

Think, Discuss and write

When two triangles, say ABC and PQR are given, there are, in all, six possible matchings or correspondences. Two of them are

(i) ABC ↔ PQR and (ii) ABC ↔ QRP.

Find the other four correspondences by using two cutouts of triangles. Will all these correspondences lead to congruence? Think about it.

Exercise 7.1

1. Complete the following statements:

(a) Two line segments are congruent if ___________.

(b) Among two congruent angles, one has a measure of 70°; the measure of the other angle is ___________.

(c) When we write ∠A = ∠B, we actually mean ___________.

2. Give any two real-life examples for congruent shapes.

3. If ∆ABC ≅ ∆FED under the correspondence ABC ↔ FED, write all the corresponding congruent parts of the triangles.

4. If ∆DEF ≅ ∆BCA, write the part(s) of ∆BCA that correspond to

(i) ∠E (ii)  (iii) ∠F (iv)

(iii) ∠F (iv)

7.6 Criteria for Congruence of Triangles

We make use of triangular structures and patterns frequently in day-to-day life. So, it is rewarding to find out when two triangular shapes will be congruent. If you have two triangles drawn in your notebook and want to verify if they are congruent, you cannot everytime cut out one of them and use method of superposition. Instead, if we can judge congruency in terms of approrpriate measures, it would be quite useful. Let us try to do this.

A Game

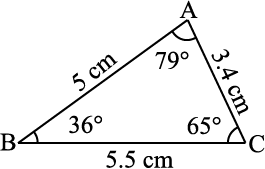

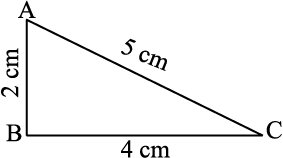

Appu and Tippu play a game. Appu has drawn a triangle ABC (Fig 7.8) and has noted the length of each of its sides and measure of each of its angles. Tippu has not seen it. Appu challenges Tippu if he can draw a copy of his ∆ABC based on bits of information that Appu would give. Tippu attempts to draw a triangle congruent to ∆ABC, using the information provided by Appu.

The game starts. Carefully observe their conversation and their games.

Fig 7.8

Triangle drawn by Appu

SSS Game

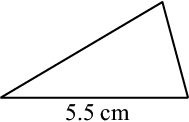

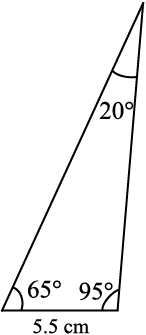

Appu : One side of ∆ABC is 5.5 cm.

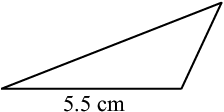

Tippu : With this information, I can draw any number of triangles (Fig 7.9) but they need not be copies of ∆ABC. The triangle I draw may be obtuse-angled or right-angled or acute-angled. For example, here are a few.

So, giving only one side-length will not help me to produce a copy of ∆ABC.

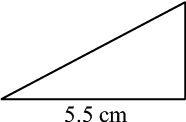

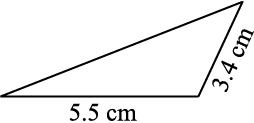

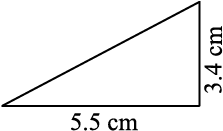

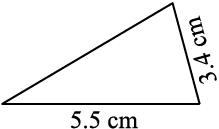

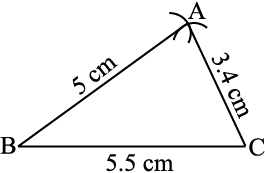

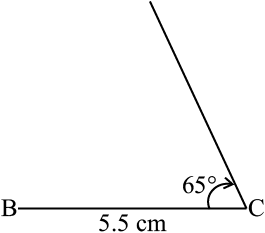

Appu : Okay. I will give you the length of one more side. Take two sides of ∆ABC to be of lengths 5.5 cm and 3.4 cm.

Tippu : Even this will not be sufficient for the purpose. I can draw several triangles

(Fig 7.10) with the given information which may not be copies of ∆ABC. Here are a few to support my argument:

Fig 7.10

One cannot draw an exact copy of your triangle, if only the lengths of two sides are given.

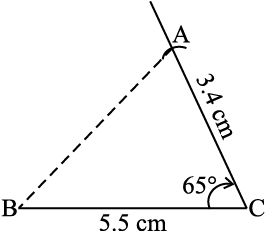

Appu : Alright. Let me give the lengths of all the three sides. In ∆ABC, I have AB = 5cm, BC = 5.5 cm and AC = 3.4 cm.

Tippu : I think it should be possible. Let me try now.

First I draw a rough figure so that I can remember the lengths easily.

Fig 7.11

I draw with length 5.5 cm.

With B as centre, I draw an arc of radius 5 cm. The point A has to be somewhere on this arc. With C as centre, I draw an arc of radius 3.4 cm. The point A has to be on this arc also.

So, A lies on both the arcs drawn. This means A is the point of intersection of the arcs.

I know now the positions of points A, B and C. Aha! I can join them and get ∆ABC (Fig 7.11).

Appu : Excellent. So, to draw a copy of a given ∆ABC (i.e., to draw a triangle congruent to ∆ABC), we need the lengths of three sides. Shall we call this condition as side-side-side criterion?

Tippu : Why not we call it SSS criterion, to be short?

SSS Congruence criterion:

If under a given correspondence, the three sides of one triangle are equal to the three corresponding sides of another triangle, then the triangles are congruent.

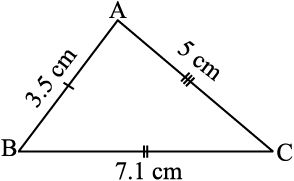

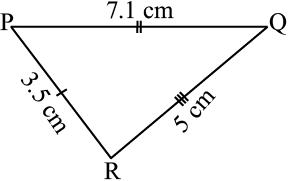

Example 2 In triangles ABC and PQR, AB = 3.5 cm, BC = 7.1 cm, AC = 5 cm, PQ = 7.1 cm, QR = 5 cm and PR = 3.5 cm. Examine whether the two triangles are congruent or not. If yes, write the congruence relation in symbolic form.

Solution Here, AB = PR (= 3.5 cm),

BC = PQ ( = 7.1 cm)

and AC = QR (= 5 cm)

This shows that the three sides of one triangle are equal to the three sides of the other triangle. So, by SSS congruence rule, the two triangles are congruent. From the above three equality relations, it can be easily seen that A ↔ R, B ↔ P and C ↔ Q.

So, we have ∆ABC ≅ ∆RPQ

Fig 7.12

Important note: The order of the letters in the names of congruent triangles displays the corresponding relationships. Thus, when you write ∆ABC ≅ ∆RPQ, you would know that A lies on R, B on P, C on Q,  along

along  ,

,  along

along  and

and  along

along  .

.

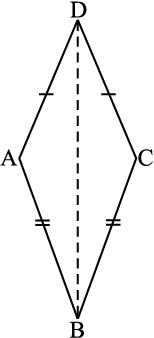

Example 3 In Fig 7.13, AD = CD and AB = CB.

(ii) Is ∆ABD ≅ ∆CBD? Why or why not?

(iii) Does BD bisect ∠ABC? Give reasons.

![]() Fig 7.13

Fig 7.13

Solution

(i) In ∆ABD and ∆CBD, the three pairs of equal parts are as given below:

AB = CB (Given)

AD = CD (Given)

and BD = BD (Common in both)

(ii) From (i) above, ∆ABD ≅ ∆CBD (By SSS congruence rule)

(iii) ∠ABD = ∠CBD (Corresponding parts of congruent triangles)

So, BD bisects ∠ABC.

Try These

(iii)

(iv)

Fig 7.14

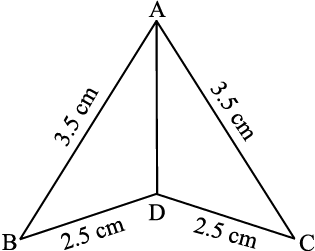

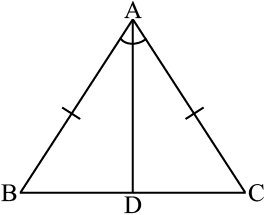

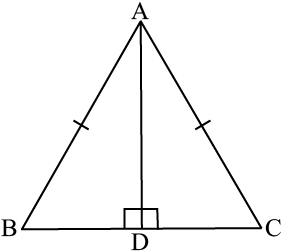

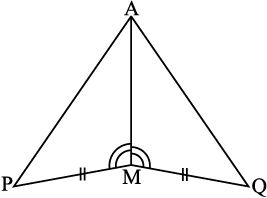

2. In Fig 7.15, AB = AC and D is the mid-point of  .

.

(i) State the three pairs of equal parts in ∆ADB and ∆ADC.

(ii) Is ∆ADB ≅ ∆ADC? Give reasons.

(iii) Is ∠B = ∠C? Why?

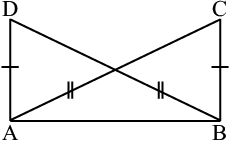

3. In Fig 7.16, AC = BD and AD = BC. Which

of the following statements is meaningfully written?

(i) ∆ABC ≅ ∆ABD (ii) ∆ABC ≅ ∆BAD.

Fig 7.15

Fig 7.16

Think, Discuss and Write

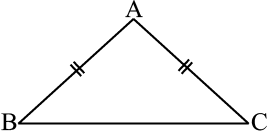

ABC is an isosceles triangle with AB = AC (Fig 7.17).

Take a trace-copy of ∆ABC and also name it as ∆ABC.

(i) State the three pairs of equal parts in ∆ABC and ∆ACB.

(ii) Is ∆ABC ≅ ∆ACB? Why or why not?

(iii) Is ∠B = ∠C ? Why or why not?

Appu and Tippu now turn to playing the game with a slight modification.

Fig 7.17

SAS Game

Appu : Let me now change the rules of the triangle-copying game.

Tippu : Right, go ahead.

Appu : You have already found that giving the length of only one side is useless.

Tippu : Of course, yes.

Appu : In that case, let me tell that in ∆ABC, one side is 5.5 cm and one angle is 65°.

Tippu : This again is not sufficient for the job. I can find many triangles satisfying your information, but are not copies of ∆ABC. For example, I have given here some of them

(Fig 7.18):

Fig 7.18

Appu : So, what shall we do?

Tippu : More information is needed.

Appu : Then, let me modify my earlier statement. In ∆ABC, the length of two sides are 5.5 cm and 3.4 cm, and the angle between these two sides is 65°.

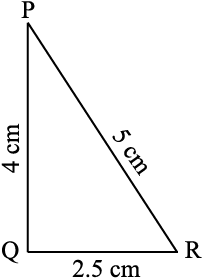

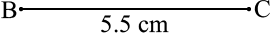

Tippu : This information should help me. Let me try. I draw first  of length 5.5. cm

of length 5.5. cm

[Fig 7.19 (i)]. Now I make 65° at C [Fig 7.19 (ii)].

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

Fig 7.19

Yes, I got it, A must be 3.4 cm away from C along this angular line through C.

I draw an arc of 3.4 cm with C as centre. It cuts the 65° line at A.

Now, I join AB and get ∆ABC [Fig 7.19(iii)].

Appu : You have used side-angle-side, where the angle is ‘included’ between the sides!

Tippu : Yes. How shall we name this criterion?

Appu : It is SAS criterion. Do you follow it?

Tippu : Yes, of course.

SAS Congruence criterion:

If under a correspondence, two sides and the angle included between them of a triangle are equal to two corresponding sides and the angle included between them of another triangle, then the triangles are congruent.

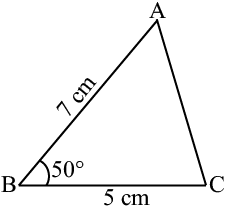

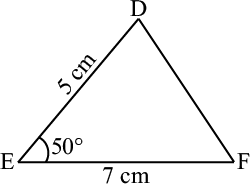

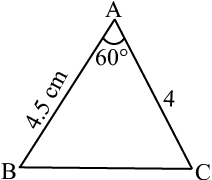

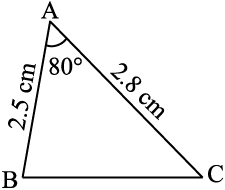

Example 4 Given below are measurements of some parts of two triangles. Examine whether the two triangles are congruent or not, by using SAS congruence rule. If the triangles are congruent, write them in symbolic form.

∆ABC ∆DEF

(a) AB = 7 cm, BC = 5 cm, ∠B = 50° DE = 5 cm, EF = 7 cm, ∠E = 50°

(b) AB = 4.5 cm, AC = 4 cm, ∠A = 60° DE = 4 cm, FD = 4.5 cm, ∠D = 55°

(c) BC = 6 cm, AC = 4 cm, ∠B = 35° DF = 4 cm, EF = 6 cm, ∠E = 35°

(It will be always helpful to draw a rough figure, mark the measurements and then probe the question).

Solution

(a) Here, AB = EF ( = 7 cm), BC = DE ( = 5 cm) and

included ∠B = included ∠E ( = 50°). Also, A ↔ F B ↔ E and C ↔ D.

Therefore, ∆ABC ≅ ∆FED (By SAS congruence rule) (Fig 7.20)

(b) Here, AB = FD and AC = DE (Fig 7.21).

But included ∠A ≠ included ∠D. So, we cannot say that the triangles are congruent.

(c) Here, BC = EF, AC = DF and ∠B = ∠E.

But ∠B is not the included angle between the sides AC and BC.

Similarly, ∠E is not the included angle between the sides EF and DF.

So, SAS congruence rule cannot be applied and we cannot conclude that the two triangles are congruent.

Fig 7.22

Example 5 In Fig 7.23, AB = AC and AD is the bisector of ∠BAC.

(i) State three pairs of equal parts in triangles ADB and ADC.

(ii) Is ∆ADB ≅ ∆ADC? Give reasons.

(iii) Is ∠B = ∠C? Give reasons.

Solution

(i) The three pairs of equal parts are as follows:

AB = AC (Given)

∠BAD = ∠CAD (AD bisects ∠BAC) and AD = AD (common)

(ii) Yes, ∆ADB ≅ ∆ADC (By SAS congruence rule)

(iii) ∠B = ∠C (Corresponding parts of congruent triangles)

Try These

1. Which angle is included between the sides  and

and  of ∆DEF?

of ∆DEF?

2. By applying SAS congruence rule, you want to establish that ∆PQR ≅ ∆FED. It is given that PQ = FE and RP = DF. What additional information is needed to establish the congruence?

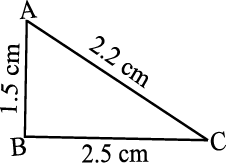

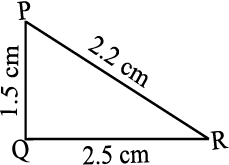

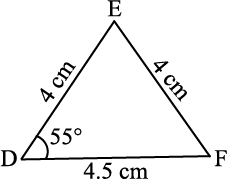

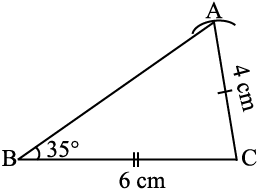

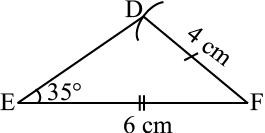

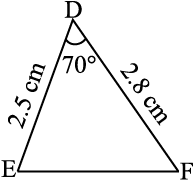

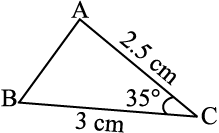

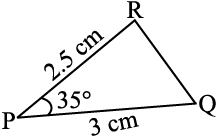

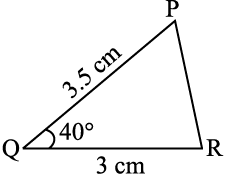

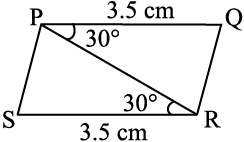

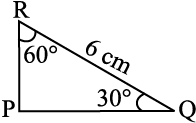

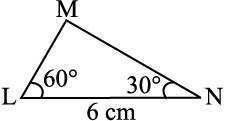

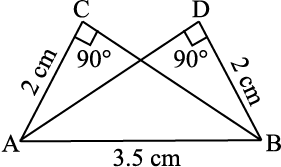

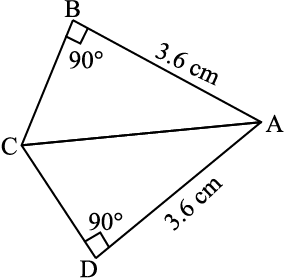

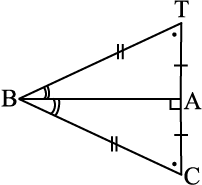

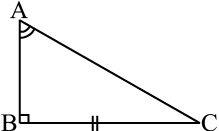

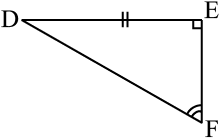

3. In Fig 7.24, measures of some parts of the triangles are indicated. By applying SAS congruence rule, state the pairs of congruent triangles, if any, in each case. In case of congruent triangles, write them in symbolic form.

(iv)

Fig 7.24

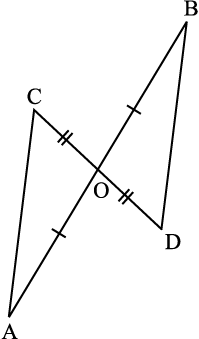

4. In Fig 7.25,  and

and  bisect each other at O.

bisect each other at O.

(i) State the three pairs of equal parts in two triangles AOC and BOD.

(ii) Which of the following statements are true?

(a) ∆AOC ≅ ∆DOB

(b) ∆AOC ≅ ∆BOD

Fig 7.25

ASA Game

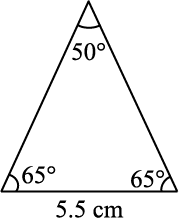

Can you draw Appu’s triangle, if you know

(i) only one of its angles? (ii) only two of its angles?

(iii) two angles and any one side?

(iv) two angles and the side included between them?

Attempts to solve the above questions lead us to the following criterion:

ASA Congruence criterion:

If under a correspondence, two angles and the included side of a triangle are equal to two corresponding angles and the included side of another triangle, then the triangles are congruent.

Example 6 By applying ASA congruence rule, it is to be established that ∆ABC ≅ ∆QRP and it is given that BC = RP. What additional information is needed to establish the congruence?

Solution For ASA congruence rule, we need the two angles between which the two sides BC and RP are included. So, the additional information is as follows:

∠B = ∠R

and ∠C = ∠P

Fig 7.26

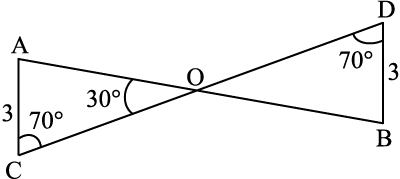

Example 7 In Fig 7.26, can you use ASA congruence

rule and conclude that ∆AOC ≅ ∆BOD?

Solution In the two triangles AOC and BOD, ∠C = ∠D (each 70° )

Also, ∠AOC = ∠BOD = 30° (vertically opposite angles)

So, ∠A of ∆AOC = 180° – (70° + 30°) = 80°

(using angle sum property of a triangle)

Similarly, ∠B of ∆BOD = 180° – (70° + 30°) = 80°

Thus, we have ∠A = ∠B, AC = BD and ∠C = ∠D

Now, side AC is between ∠A and ∠C and side BD is between ∠B and ∠D.

So, by ASA congruence rule, ∆AOC ≅ ∆BOD.

Remark

Given two angles of a triangle, you can always find the third angle of the triangle. So, whenever, two angles and one side of one triangle are equal to the corresponding two angles and one side of another triangle, you may convert it into ‘two angles and the included side’ form of congruence and then apply the ASA congruence rule.

Try These

2. You want to establish ∆DEF ≅ ∆MNP, using the ASA congruence rule. You are given that ∠D = ∠M and ∠F = ∠P. What information is needed to establish the congruence? (Draw a rough figure and then try!)

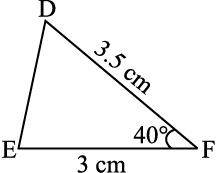

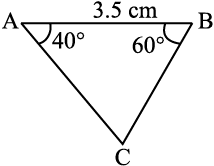

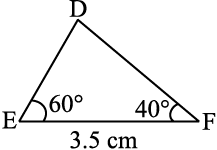

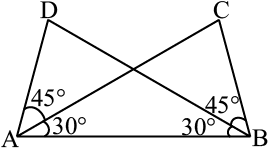

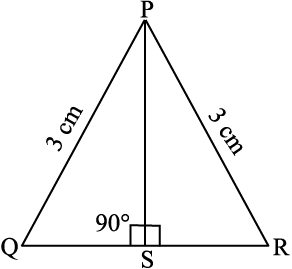

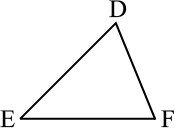

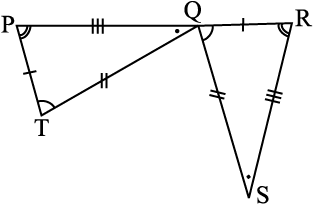

3. In Fig 7.27, measures of some parts are indicated. By applying ASA congruence rule, state which pairs of triangles are congruent. In case of congruence, write the result in symoblic form.

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

Fig 7.27

4. Given below are measurements of some parts of two triangles. Examine whether the two triangles are congruent or not, by ASA congruence rule. In case of congruence, write it in symbolic form.

∆DEF ∆PQR

(i) ∠D = 60º, ∠F = 80º, DF = 5 cm ∠Q = 60º, ∠R = 80º, QR = 5 cm

(ii) ∠D = 60º, ∠F = 80º, DF = 6 cm ∠Q = 60º, ∠R = 80º, QP = 6 cm

(iii) ∠E = 80º, ∠F = 30º, EF = 5 cm ∠P = 80º, PQ = 5 cm, ∠R = 30º

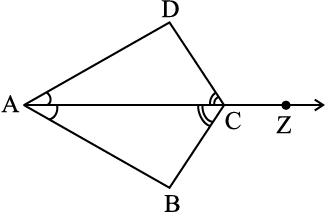

5. In Fig 7.28, ray AZ bisects ∠DAB as well as ∠DCB.

(i) State the three pairs of equal parts in triangles BAC and DAC.

(ii) Is ∆BAC ≅ ∆DAC? Give reasons.

(iii) Is AB = AD? Justify your answer.

(iv) Is CD = CB? Give reasons.

Fig 7.28

7.7 Congruence Among Right-angled Triangles

Congruence in the case of two right triangles deserves special attention. In such triangles, obviously, the right angles are equal. So, the congruence criterion becomes easy.

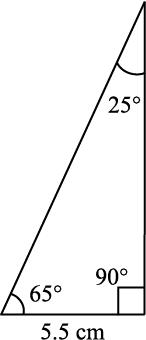

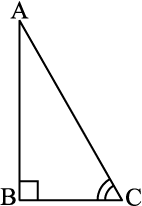

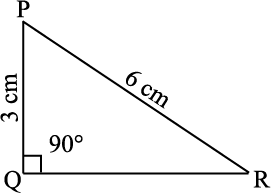

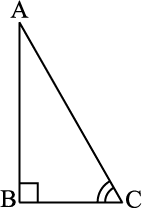

Can you draw ∆ABC (shown in Fig 7.29) with ∠B = 90°, if

(i) only BC is known? (ii) only ∠C is known?

(iii) ∠A and ∠C are known? (iv) AB and BC are known?

(v) AC and one of AB or BC are known?

Fig 7.29

Try these with rough sketches. You will find that (iv) and (v) help you to draw the triangle. But case (iv) is simply the SAS condition. Case (v) is something new. This leads to the following criterion:

RHS Congruence criterion:

If under a correspondence, the hypotenuse and one side of a right-angled triangle are respectively equal to the hypotenuse and one side of another right-angled triangle, then the triangles are congruent.

Why do we call this ‘RHS’ congruence? Think about it.

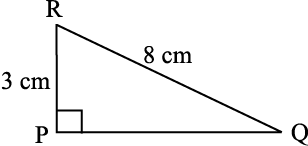

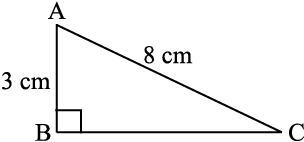

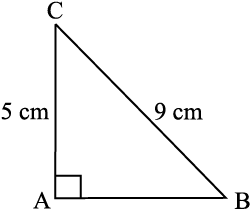

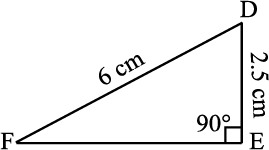

Example 8 Given below are measurements of some parts of two triangles. Examine whether the two triangles are congruent or not, using RHS congruence rule. In case of congruent triangles, write the result in symbolic form:

∆ABC ∆PQR

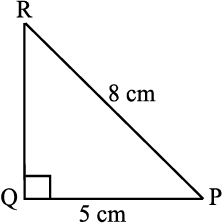

(i) ∠B = 90°, AC = 8 cm, AB = 3 cm ∠P = 90°, PR = 3 cm, QR = 8 cm

(ii) ∠A = 90°, AC = 5 cm, BC = 9 cm ∠Q = 90°, PR = 8 cm, PQ = 5 cm

Solution

(i) Here, ∠B = ∠P = 90º,

hypotenuse, AC = hypotenuse, RQ (= 8 cm) and

side AB = side RP ( = 3 cm)

So, ∆ABC ≅ ∆RPQ (By RHS Congruence rule). [Fig 7.30(i)]

(ii)

Fig 7.30

(ii) Here, ∠A = ∠Q(= 90°) and

side AC = side PQ ( = 5 cm).

But hypotenuse BC ≠ hypotenuse PR [Fig 7.30(ii)]

So, the triangles are not congruent.

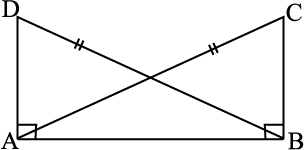

Example 9 In Fig 7.31, DA ⊥ AB, CB ⊥ AB and AC = BD.

State the three pairs of equal parts in ∆ABC and ∆DAB.

Which of the following statements is meaningful?

(i) ∆ABC ≅ ∆BAD (ii) ∆ABC ≅ ∆ABD

Fig 7.31

Solution The three pairs of equal parts are:

∠ABC = ∠BAD (= 90°)

AB = BA (Common side)

From the above, ∆ABC ≅ ∆BAD (By RHS congruence rule).

So, statement (i) is true

Statement (ii) is not meaningful, in the sense that the correspondence among the vertices is not satisfied.

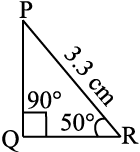

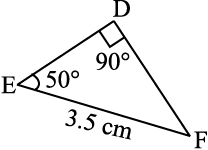

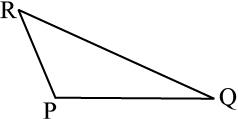

Try These

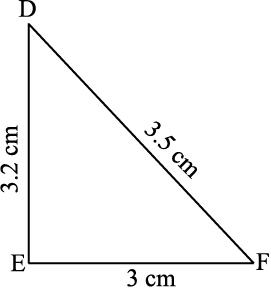

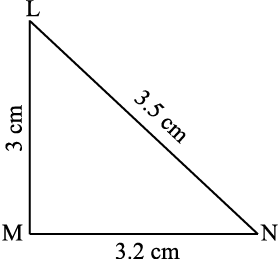

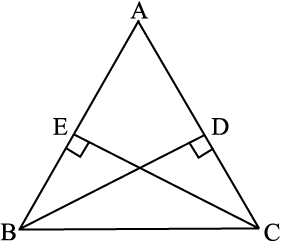

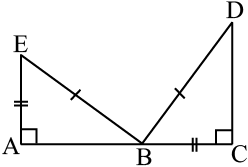

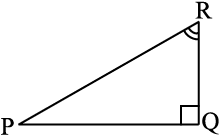

1. In Fig 7.32, measures of some parts of triangles are given.By applying RHS congruence rule, state which pairs of triangles are congruent. In case of congruent triangles, write the result in symbolic form.

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

Fig 7.32

Fig 7.33

Fig 7.34

2. It is to be established by RHS congruence rule that ∆ABC ≅ ∆RPQ. What additional information is needed, if it is given that

∠B = ∠P = 90º and AB = RP?

3. In Fig 7.33, BD and CE are altitudes of ∆ABC such that BD = CE.

(i) State the three pairs of equal parts in ∆CBD and ∆BCE.

(ii) Is ∆CBD ≅ ∆BCE? Why or why not?

(iii) Is ∠DCB = ∠EBC? Why or why not?

4. ABC is an isosceles triangle with AB = AC and AD is one of its altitudes (Fig 7.34).

(i) State the three pairs of equal parts in ∆ADB and ∆ADC.

(ii) Is ∆ADB ≅ ∆ADC? Why or why not?

(iii) Is ∠B = ∠C? Why or why not?

(iv) Is BD = CD? Why or why not?

We now turn to examples and problems based on the criteria seen so far.

Exercise 7.2

(a) Given: AC = DF

AB = DE

BC = EF

So, ∆ABC ≅ ∆DEF

(b) Given: ZX = RP

RQ = ZY

∠PRQ = ∠XZY

So, ∆PQR ≅ ∆XYZ

(c) Given: ∠MLN = ∠FGH

∠NML = ∠GFH

ML = FG

So, ∆LMN ≅ ∆GFH

(d) Given: EB = DB

AE = BC

∠A = ∠C = 90°

So, ∆ABE ≅ ∆CDB

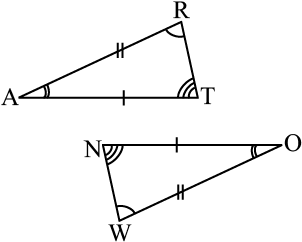

2. You want to show that ∆ART ≅ ∆PEN,

(a) If you have to use SSS criterion, then you need to show

(i) AR = (ii) RT = (iii) AT =

(i) RT = and (ii) PN =

(c) If it is given that AT = PN and you are to use ASA criterion, you need to have

(i) ? (ii) ?

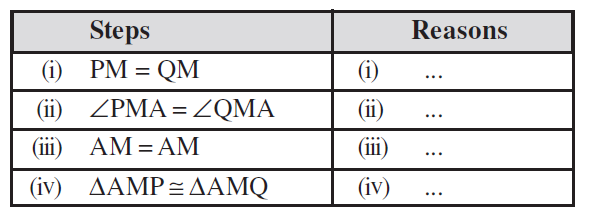

In the following proof, supply the missing reasons.

4. In ∆ABC, ∠A = 30° , ∠B = 40° and ∠C = 110°

In ∆PQR, ∠P = 30° , ∠Q = 40° and ∠R = 110°

A student says that ∆ABC ≅ ∆PQR by AAA congruence criterion. Is he justified? Why or why not?

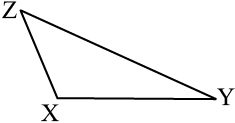

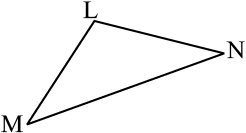

5. In the figure, the two triangles are congruent. The corresponding parts are marked. We can write ∆RAT ≅ ?

6. Complete the congruence statement:

∆BCA ≅ ? ∆QRS ≅ ?

7. In a squared sheet, draw two triangles of equal areas such that

(i) the triangles are congruent.

(ii) the triangles are not congruent.

What can you say about their perimeters?

8. Draw a rough sketch of two triangles such

but still the triangles are not congruent.

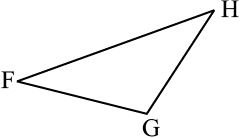

9. If ∆ABC and ∆PQR are to be congruent,

name one additional pair of corresponding

parts. What criterion did you use?

10. Explain, why

∆ABC ≅ ∆FED.

Enrichment activity

We saw that superposition is a useful method to test congruence of plane figures. We discussed conditions for congruence of line segments, angles and triangles. You can now try to extend this idea to other plane figures as well.

1. Consider cut-outs of different sizes of squares. Use the method of superposition to find out the condition for congruence of squares. How does the idea of ‘corresponding parts’ under congruence apply? Are there corresponding sides? Are there corresponding diagonals?

2. What happens if you take circles? What is the condition for congruence of two circles? Again, you can use the method of superposition. Investigate.

3. Try to extend this idea to other plane figures like regular hexagons, etc.

4. Take two congruent copies of a triangle. By paper folding, investigate if they have equal altitudes. Do they have equal medians? What can you say about their perimeters and areas?

What have we Discussed?

1. Congruent objects are exact copies of one another.

2. The method of superposition examines the congruence of plane figures.

3. Two plane figures, say, F1 and F2 are congruent if the trace-copy of F1 fits exactly on that of F2. We write this as F1 ≅ F2.

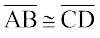

4. Two line segments, say,  and

and  , are congruent if they have equal lengths. We write this as

, are congruent if they have equal lengths. We write this as  . However, it is common to write it as

. However, it is common to write it as  =

=  .

.

5. Two angles, say, ∠ABC and ∠PQR, are congruent if their measures are equal. We write this as ∠ABC ≅ ∠PQR or as m∠ABC = m∠PQR. However, in practice, it is common to write it as ∠ABC = ∠PQR.

6. SSS Congruence of two triangles:

Under a given correspondence, two triangles are congruent if the three sides of the one are equal to the three corresponding sides of the other.

7. SAS Congruence of two triangles:

8. ASA Congruence of two triangles:

Under a given correspondence, two triangles are congruent if two angles and the side included between them in one of the triangles are equal to the corresponding angles and the side included between them of the other triangle.

9. RHS Congruence of two right-angled triangles:

Under a given correspondence, two right-angled triangles are congruent if the hypotenuse and a leg of one of the triangles are equal to the hypotenuse and the corresponding leg of the other triangle.

10. There is no such thing as AAA Congruence of two triangles:

Two triangles with equal corresponding angles need not be congruent. In such a correspondence, one of them can be an enlarged copy of the other. (They would be congruent only if they are exact copies of one another).