Table of Contents

5

RULERS AND BUILDINGS

Figure 1 shows the first balcony of the Qutb Minar.

Qutbuddin Aybak had this constructed around 1199. Notice the pattern created under the balcony by the small arches and geometrical designs. Can you see two bands of inscriptions under the balcony? These are in Arabic. Notice that the surface of the minar is curved and angular. Placing an inscription on such a surface required great precision. Only the most skilled craftsperson could perform this task. Remember that very few buildings were made of stone or brick 800 years ago. What would have been the impact of a building like the Qutb Minar on observers in the thirteenth century?

Between the eighth and the eighteenth centuries kings and their officers built two kinds of structures:

Fig. 1

The Qutb Minar is five storeys high. The band of inscriptions you see are under its first balcony.

The first floor was constructed by Qutbuddin Aybak and the rest by Iltutmish around 1229. Over the years it was damaged by lightning and earthquakes and repaired by Alauddin Khalji, Muhammad Tughluq, Firuz Shah Tughluq and Ibrahim Lodi.

the first were forts, palaces, garden residences and tombs – safe, protected and grandiose places of rest in this world and the next; the second were structures meant for public activity including temples, mosques, tanks, wells, caravanserais and bazaars. Kings were expected to care for their subjects, and by making structures for their use and comfort, rulers hoped to win their praise. Construction activity was also carried out by others, including merchants. They built temples, mosques and wells. However, domestic architecture – large mansions (havelis) of merchants – has survived only from the eighteenth century.

Labour for the Agra Fort

Built by Akbar, the Agra Fort required 2,000 stone-cutters, 2,000 cement and lime-makers and 8,000 labourers.

Engineering Skills and Construction

Monuments provide an insight into the technologies used for construction. Take something like a roof for example. We can make this by placing wooden beams or a slab of stone across four walls. But the task becomes difficult if we want to make a large room with an elaborate superstructure. This requires more sophisticated skills.

Raniji ki baori or the ‘Queen’s Stepwell’, located in Bundi in Rajasthan is the largest among the fifty step wells that were built to meet the need for water. Known for its architectural beauty, the baori was constructed in 1699 C.E. by Rani Nathavat Ji, the queen of Raja Anirudh Singh of Bundi.

Between the seventh and tenth centuries architects started adding more rooms, doors and windows to buildings. Roofs, doors and windows were still made by placing a horizontal beam across two vertical columns, a style of architecture called “trabeate” or “corbelled”. Between the eighth and thirteenth centuries the trabeate style was used in the construction of temples, mosques, tombs and in buildings attached to large stepped-wells (baolis).

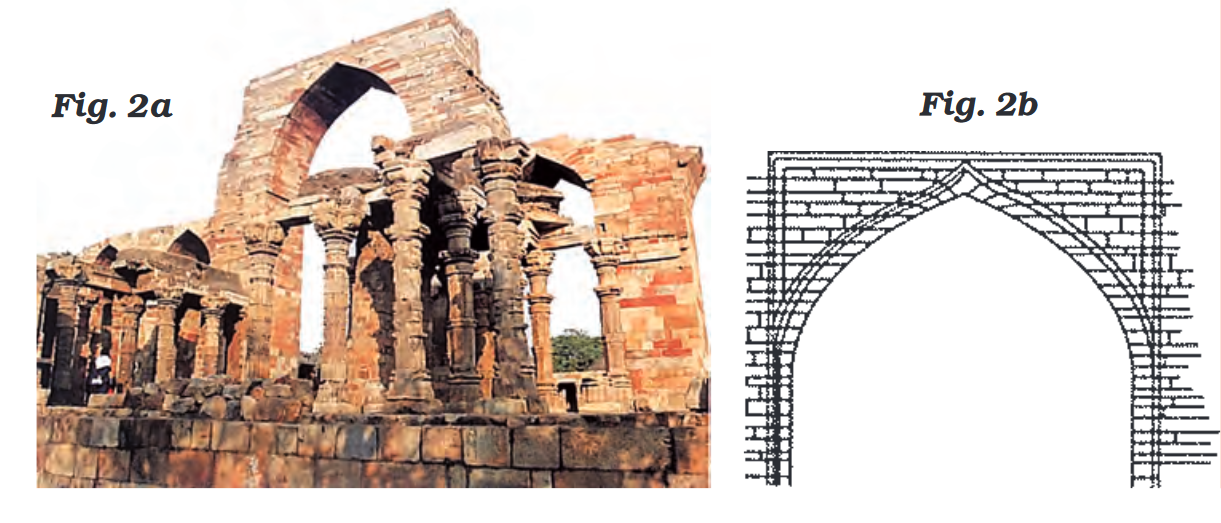

Fig. 2a

Screen in the Quwwat al-Islam mosque, Delhi (late twelfth century).

Fig. 2b

Corbelled technique used in the construction of the screen.

Temple Construction in the Early Eleventh Century

The Kandariya Mahadeva temple dedicated to Shiva was constructed in 999 by the king Dhangadevaof the Chandela dynasty. Fig. 3b is the plan of the temple. An ornamented gateway led to an entrance, and the main hall (mahamandapa) where dances were performed. The image of the chief deity was kept in the main shrine (garbhagriha). This was the place for ritual worship where only the king, his immediate family and priests gathered. The Khajuraho complex contained royal temples where commoners were not allowed entry. The temples were decorated with elaborately carved sculptures.

Fig. 4

The Rajarajeshvara temple at Thanjavur had the tallest shikhara amongst temples of its time. Constructing it was not easy because there were no cranes in those days and the 90 tonne stone for the top of the shikhara was too heavy to lift manually. So the architects built an inclined path to the top of the temple, placed the boulder on rollers and rolled it all the way to the top. The path started more than 4 km away so that it would not be too steep. This was dismantled after the temple was constructed. But the residents of the area remembered the experience of the construction of the temple for a long time. Even now a village near the temple is called Charupallam, the “Village of the Incline”.

What differences do you notice between the shikharas of the two temples? Can you make out that the shikhara of the Rajarajeshvara temple is twice as high as that of the Kandariya Mahadeva?

Two technological and stylistic developments are noticeable from the twelfth century.

(1) The weight of the superstructure above the doors and windows was sometimes carried by arches. This architectural form was called “arcuate”.

Fig. 5a

A “true” arch. The “keystone” at the centre of the arch transferred the weight of the superstructure to the base of the arch.

Fig. 5b

True arch; detail from the Alai Darwaza (early fourteenth century). Quwwat al-Islam mosque, Delhi.

Compare Figures 2a and 2b with Figures 5a and 5b.

(2) Limestone cement was increasingly used in construction. This was very high-quality cement, which, when mixed with stone chips hardened into concrete. This made construction of large structures easier and faster. Take a look at the construction site in Figure 6.

Fig. 6

A painting from the Akbar Nama (dated 1590-1595), showing the construction of the water-gate at the Agra Fort.

Describe what the labourers are doing, the tools shown, and the means of carrying stones.

Building Temples, Mosques and Tanks

Temples and mosques were beautifully constructed because they were places of worship. They were also meant to demonstrate the power, wealth and devotion of the patron. Take the example of the Rajarajeshvara temple. An inscription mentions that it was built by King Rajarajadeva for the worship of his god, Rajarajeshvaram. Notice how the names of the ruler and the god are very similar. The king took the god’s name because it was auspicious and he wanted to appear like a god. Through the rituals of worship in the temple one god (Rajarajadeva) honoured another (Rajarajeshvaram).

The largest temples were all constructed by kings. The other, lesser deities in the temple were gods and goddesses of the allies and subordinates of the ruler. The temple was a miniature model of the world ruled by the king and his allies. As they worshipped their deities together in the royal temples, it seemed as if they brought the just rule of the gods on earth.

Muslim Sultans and Padshahs did not claim to be incarnations of god but Persian court chronicles described the Sultan as the “Shadow of God”. An inscription in the Quwwat al-Islam mosque explained that God chose Alauddin as a king because he had the qualities of Moses and Solomon, the great lawgivers of the past. The greatest lawgiver and architect was God Himself. He created the world out of chaos and introduced order and symmetry.

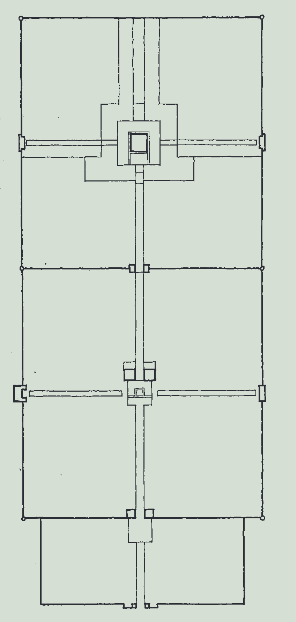

Fig. 7

Plan of the Jami Masjid built by Shah Jahan in his new capital at Shahjahanabad, 1650-1656.

As each new dynasty came to power, kings wanted to emphasise their moral right to be rulers. Constructing places of worship provided rulers with the chance to proclaim their close relationship with God, especially important in an age of rapid political change. Rulers also offered patronage to the learned and pious, and tried to transform their capitals and cities into great cultural centres that brought fame to their rule and their realm.

It was widely believed that the rule of a just king would be an age of plenty when the heavens would not withhold rain. At the same time, making precious water available by constructing tanks and reservoirs was highly praised. Sultan Iltutmish won universal respect for constructing a large reservoir just outside Dehli-i-Kuhna. It was called the Hauz-i-Sultani or the “King’s Reservoir”. Can you find it on Map 1 in Chapter 3? Rulers often constructed tanks and reservoirs – big and small – for use by ordinary people. Sometimes these tanks and reservoirs were part of a temple, mosque (note the small tank in the Jami Masjid in Fig. 7) or a gurdwara (a place of worship and congregation for Sikhs, Fig. 8).

Fig. 8

Harmandar Sahib (Golden Temple) with the holy sarovar (tank) in Amritsar.

Why were Temples Destroyed?

Because kings built temples to demonstrate their devotion to God and their power and wealth, it is not surprising that when they attacked one another’s kingdoms they often targeted these buildings. In the early ninth century when the Pandyan king Shrimara Shrivallabha invaded Sri Lanka and defeated the king, Sena I (831-851), the Buddhist monk and chronicler Dhammakitti noted: “he removed all the valuables ... The statue of the Buddha made entirely of gold in the Jewel Palace ... and the golden images in the various monasteries – all these he seized.” The blow to the pride of the Sinhalese ruler had to be avenged and the next Sinhalese ruler, Sena II, ordered his general to invade Madurai, the capital of the Pandyas. The Buddhist chronicler noted that the expedition made a special effort to find and restore the gold statue of the Buddha.

Fig. 9

Mughal chahar baghs

(a) The chahar bagh in Humayun’s tomb, Delhi, 1562-1571.

(b) Terraced chahar bagh at Shalimar gardens, Kashmir, 1620 and 1634.

(c) The chahar bagh adapted as a river-front garden at Lal Mahal Bari, 1637.

Similarly in the early eleventh century, when the Chola king Rajendra I built a Shiva temple in his capital he filled it with prized statues seized from defeated rulers. An incomplete list included: a Sun-pedestal from the Chalukyas, a Ganesha statue and several statues of Durga; a Nandi statue from the eastern Chalukyas; an image of Bhairava (a form of Shiva) and Bhairavi from the Kalingas of Orissa; and a Kali statue from the Palas of Bengal.

Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni was a contemporary of Rajendra I. During his campaigns in the subcontinent he also attacked the temples of defeated kings and looted their wealth and idols. Sultan Mahmud was not a very important ruler at that time. But by destroying temples – especially the one at Somnath – he tried to win credit as a great hero of Islam. In the political culture of the Middle Ages most rulers displayed their political might and military success by attacking and looting the places of worship of defeated rulers.

In what ways do you think the policies of Rajendra I and Mahmud of Ghazni were a product of their times? How were the actions of the two rulers different?

Gardens, Tombs and Forts

Under the Mughals, architecture became more complex. Babur, Humayun, Akbar, Jahangir, and especially Shah Jahan were personally interested in literature, art and architecture. In his autobiography, Babur described his interest in planning and laying out formal gardens, placed within rectangular walled enclosures and divided into four quarters by artificial channels.

Fig. 10

A 1590 painting of Babur supervising workers laying out a chahar bagh in Kabul. Note how the intersecting channels on the path create the characteristic chahar bagh design.

These gardens were called chahar bagh, four gardens, because of their symmetrical division into quarters. Beginning with Akbar, some of the most beautiful chahar baghs were constructed by Jahangir and Shah Jahan in Kashmir, Agra and Delhi (see Fig. 9).

There were several important architectural innovations during Akbar’s reign. For inspiration, Akbar’s architects turned to the tombs of his Central Asian ancestor, Timur. The central towering dome and the tall gateway (pishtaq) became important aspects of Mughal architecture, first visible in Humayun’s tomb. The tomb was placed in the centre of a huge formal chahar bagh and built in the tradition known as “eight paradises” or hasht bihisht – a central hall surrounded by eight rooms. The building was constructed with red sandstone, edged with white marble.

Fig.11

Tomb of Humayun, constructed between 1562 and 1571.

Can you see the water channels?

Fig. 12

The throne balcony in the diwan-i am in Delhi, completed in 1648.

It was during Shah Jahan’s reign that the different elements of Mughal architecture were fused together in a grand harmonious synthesis. His reign witnessed a huge amount of construction activity especially in Agra and Delhi. The ceremonial halls of public and private audience (diwan-i khas o am) were carefully planned. Placed within a large courtyard, these courts were also described as chihil sutun or forty-pillared halls.

Shah Jahan’s audience halls were specially constructed to resemble a mosque. The pedestal on which his throne was placed was frequently described as the qibla, the direction faced by Muslims at prayer, since everybody faced that direction when court was in session. The idea of the king as a representative of God on earth was suggested by these architectural features.

The connection between royal justice and the imperial court was emphasised by Shah Jahan in his newly constructed court in the Red Fort at Delhi. Behind the emperor’s throne were a series of pietra dura inlays that depicted the legendary Greek god Orpheus playing the lute. It was believed that Orpheus’s music could calm ferocious beasts until they coexisted together peaceably. The construction of Shah Jahan’s audience hall aimed to communicate that the king’s justice would treat the high and the low as equals creating a world where all could live together in harmony.

Pietra dura

Coloured, hard stones placed in depressions carved into marble or sandstone creating beautiful, ornate patterns.

In the early years of his reign, Shah Jahan’s capital was at Agra, a city where the nobility had constructed their homes on the banks of the river Yamuna. These were set in the midst of formal gardens constructed in the chahar bagh format. The chahar bagh garden also had a variation that historians describe as the “river-front garden”. In this the dwelling was not located in the middle of the chahar bagh but at its edge, close to the bank of the river.

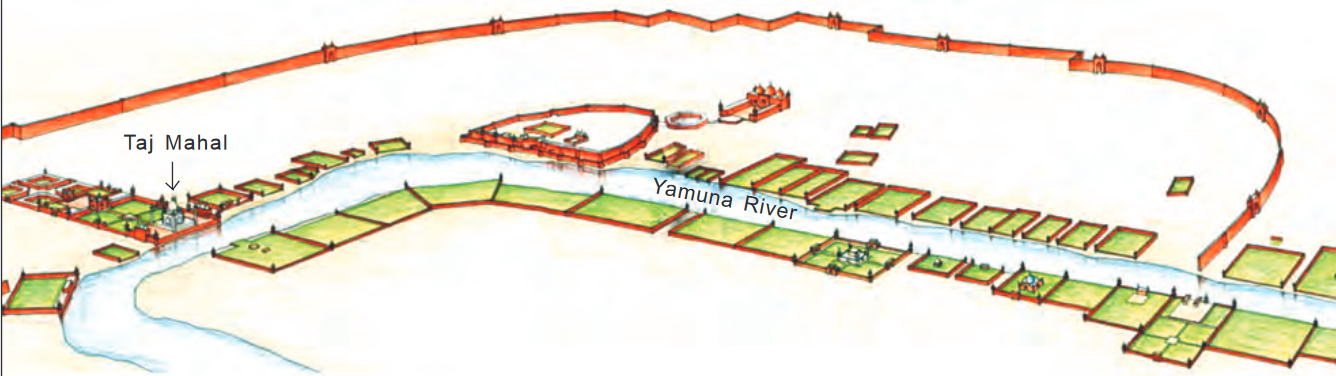

Shah Jahan adapted the river-front garden in the layout of the Taj Mahal, the grandest architectural accomplishment of his reign. Here the white marble mausoleum was placed on a terrace by the edge of the river and the garden was to its south.

Fig. 13

The Taj Mahal at Agra, completed in 1643.

Fig. 14

A reconstruction from a map of the river-front garden city of Agra. Note how the garden palaces of the nobles are placed on both banks of the Yamuna. The Taj Mahal is on the left.

Compare the layout of Agra with Shahjahanabad in Delhi in Figure15.

Fig. 15

1850 map of Shahjahanabad. Where is the emperor’s residence?

The city appears to be very crowded, but did you notice the many large gardens as well?

Can you find the main street and the jami masjid?

Shah Jahan develop this architectural form as a means to control the access that nobles had to the river. In the new city of Shahjahanabad that he constructed in Delhi, the imperial palace commanded the river-front. Only specially favoured nobles – like his eldest son Dara Shukoh – were given access to the river. All others had to construct their homes in the city away from the River Yamuna.

Region and Empire

As construction activity increased between the eighth and eighteenth centuries there was also a considerable sharing of ideas across regions: the traditions of one region were adopted by another. In Vijayanagara, for example, the elephant stables of the rulers were strongly influenced by the style of architecture found in the adjoining Sultanates of Bijapur and Golconda (see Chapter 6). In Vrindavan, near Mathura, temples were constructed in architectural styles that were very similar to the Mughal palaces in Fatehpur Sikri.

Fig. 16

Interior of temple of Govind Deva in Vrindavan, 1590.

The temple was constructed out of red sandstone. Notice the two (out of four) intersecting arches that made the high-ceiling roof. This style of architecture is from north-east Iran (Khurasan) and was used in Fatehpur Sikri.

The creation of large empires that brought different regions under their rule helped in this cross-fertilisation of artistic forms and architectural styles. Mughal rulers were particularly skilled in adapting regional architectural styles in the construction of their own buildings. In Bengal, for example, the local rulers had developed a roof that was designed to resemble a thatched hut. The Mughals liked this “Bangla dome” (see Figures 11 and 12 in Chapter 9) so much that they used it in their architecture. The impact of other regions was also evident. In Akbar’s capital at Fatehpur Sikri many of the buildings show the influence of the architectural styles of Gujarat and Malwa.

Fig. 17

Decorated pillars and struts holding the extension of the roof in Jodh Bai palace in Fatehpur Sikri. These follow architectural traditions of the Gujarat region.

Even though the authority of the Mughal rulers waned in the eighteenth century, the architectural styles developed under their patronage were constantly used and adapted by other rulers whenever they tried to establish their own kingdoms.

ELSEWHERE

Churches that touched the skies

From the twelfth century onwards, attempts began in France to build churches that were taller and lighter than earlier buildings. This architectural style, known as Gothic, was distinguished by high pointed arches, the use of stained glass, often painted with scenes drawn from the Bible, and flying buttresses. Tall spires and bell towers which were visible from a distance were added to the church.

One of the best-known examples of this architectural style is the church of Notre Dame in Paris, which was constructed through several decades in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Look at the illustration and try and identify the bell towers.

Imagine

Imagine

You are an artisan standing on a tiny wooden platform held together by bamboo and rope fifty metres above the ground. You have to place an inscription under the first balcony of the Qutb Minar. How would you do this?

KEYWORDS

Go through the chapter and make your own list of six keywords.

For each of these, write a sentence indicating why you chose the word.

Let’s recall

1. How is the “trabeate” principle of architecture different from the “arcuate”?

2. What is a shikhara?

3. What is pietra-dura?

4. What are the elements of a Mughal chahar bagh garden?

Let’s understand

5. How did a temple communicate the importance of a king?

6. An inscription in Shah Jahan’s diwan-i khas in Delhi stated: “If there is Paradise on Earth, it is here, it is here, it is here.” How was this image created?

7. How did the Mughal court suggest that everyone – the rich and the poor, the powerful and the weak – received justice equally from the emperor?

8. What role did the Yamuna play in the layout of the new Mughal city at Shahjahanabad?

Let’s discuss

9. The rich and powerful construct large houses today. In what ways were the constructions of kings and their courtiers different in the past?

10. Look at Figure 4. How could that building be constructed faster today?

Let’s do

11. Find out whether there is a statue of or a memorial to a great person in your village or town. Why was it placed there? What purpose does it serve?

12. Visit and describe any park or garden in your neighbourhood. In what ways is it similar to or different from the gardens of the Mughals?