Table of Contents

6

Towns, traders and craftspersons

What would a traveller visiting a medieval town expect to find? This would depend on what kind of a town it was – a temple town, an administrative centre, a commercial town or a port town to name just some possibilities. In fact, many towns combined several functions – they were administrative centres, temple towns, as well as centres of commercial activities and craft production.

Map 1

Some important centres of trade and artisanal production in central and south India.

Administrative Centres

You read about the Chola dynasty in Chapter 2. Let’s travel in our imagination to Thanjavur, the capital of the Cholas, as it was a thousand years ago.

The perennial river Kaveri flows near this beautiful town. One hears the bells of the Rajarajeshvara temple built by King Rajaraja Chola. The towns people are all praise for its architect Kunjaramallan Rajaraja Perunthachchan who has proudly carved his name on the temple wall. Inside is a massive Shiva linga.

Besides the temple, there are palaces with mandapas or pavilions. Kings hold court in these mandapas, issuing orders to their subordinates. There are also barracks for the army.

Why do you think people regarded Thanjavur as a great town?

The town is bustling with markets selling grain, spices, cloth and jewellery. Water supply for the town comes from wells and tanks. The Saliya weavers of Thanjavur and the nearby town of Uraiyur are busy producing cloth for flags to be used in the temple festival, fine cottons for the king and nobility and coarse cotton for the masses. Some distance away at Svamimalai, the sthapatis or sculptors are making exquisite bronze idols and tall, ornamental bell metal lamps.

Temple Towns and Pilgrimage Centres

Thanjavur is also an example of a temple town. Temple towns represent a very important pattern of urbanisation, the process by which cities develop. Temples were often central to the economy and society. Rulers built temples to demonstrate their devotion to various deities. They also endowed temples with grants of land and money to carry out elaborate rituals, feed pilgrims and priests and celebrate festivals. Pilgrims who flocked to the temples also made donations.

Bronze, bell metal and the “lost wax” technique

Bronze is an alloy containing copper and tin. Bell metal contains a greater proportion of tin than other kinds of bronze. This produces a bell-like sound.

Chola bronze statues (see Chapter 2) were made using the “lost wax” technique.

First, an image was made of wax. This was covered with clay and allowed to dry. Next it was heated, and a tiny hole was made in the clay cover. The molten wax was drained out through this hole. Then molten metal was poured into the clay mould through the hole. Once the metal cooled and solidified, the clay cover was carefully removed, and the image was cleaned and polished.

What do you think were the advantages of using this technique?

Fig. 1

A bronze statue of Krishna subduing the serpent demon Kaliya.

Temple authorities used their wealth to finance trade and banking. Gradually a large number of priests, workers, artisans, traders, etc. settled near the temple to cater to its needs and those of the pilgrims. Thus grew temple towns. Towns emerged around temples such as those of Bhillasvamin (Bhilsa or Vidisha in Madhya Pradesh), and Somnath in Gujarat. Other important temple towns included Kanchipuram and Madurai in Tamil Nadu, and Tirupati in Andhra Pradesh.

Pilgrimage centres also slowly developed into townships. Vrindavan (Uttar Pradesh) and Tiruvannamalai (Tamil Nadu) are examples of two such towns. Ajmer (Rajasthan) was the capital of the Chauhan kings in the twelfth century and later became the suba headquarters under the Mughals. It provides an excellent example of religious coexistence. Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti, the celebrated Sufi saint (see also Chapter 8) who settled there in the twelfth century, attracted devotees from all creeds. Near Ajmer is a lake, Pushkar, which has attracted pilgrims from ancient times.

Make a list of towns in your district and try to classify these as administrative centres or as temple/pilgrim centres.

A Network of Small Towns

From the eighth century onwards the subcontinent was dotted with several small towns. These probably emerged from large villages. They usually had a mandapika (or mandi of later times) to which nearby villagers brought their produce to sell. They also had market streets called hatta (haat of later times) lined with shops. Besides, there were streets for different kinds of artisans such as potters, oil pressers, sugar makers, toddy makers, smiths, stonemasons, etc. While some traders lived in the town, others travelled from town to town. Many came from far and near to these towns to buy local articles and sell products of distant places like horses, salt, camphor, saffron, betel nut and spices like pepper.

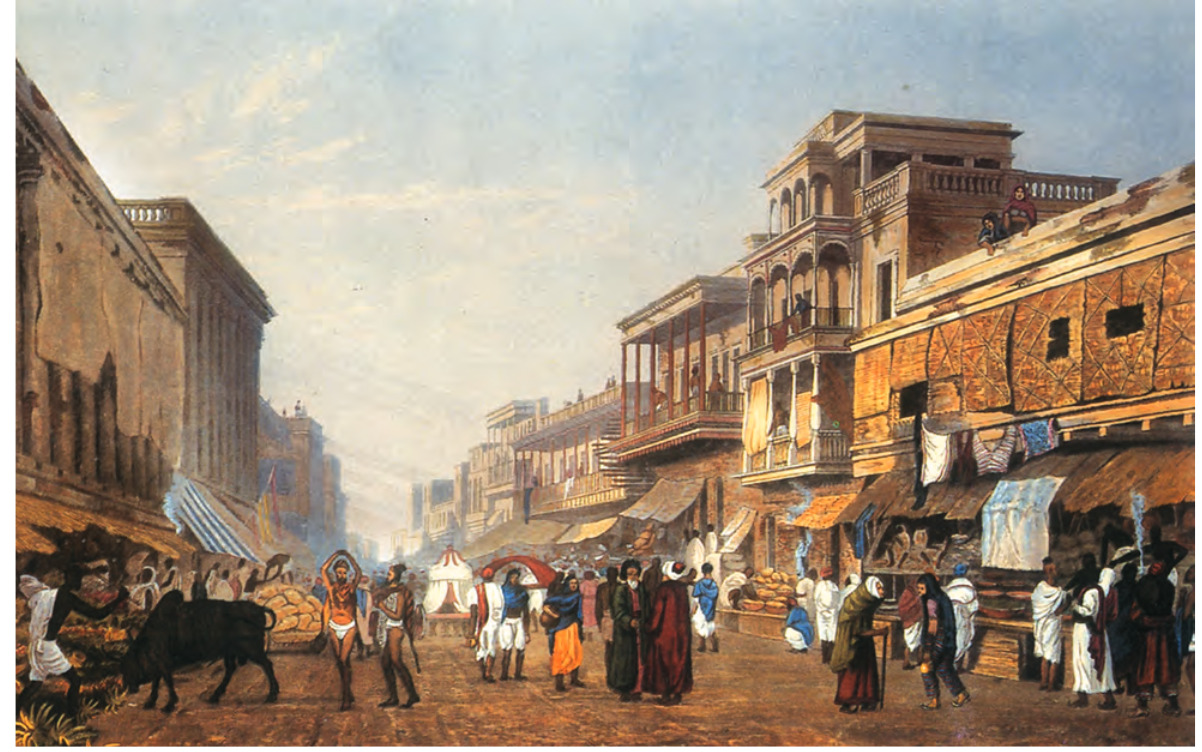

Fig. 2

A city market.

Usually a samanta or, in later times, a zamindar built a fortified palace in or near these towns. They levied taxes on traders, artisans and articles of trade and sometimes “donated” the “right” to collect these taxes to local temples, which had been built by themselves or by rich merchants. These “rights” were recorded in inscriptions that have survived to this day.

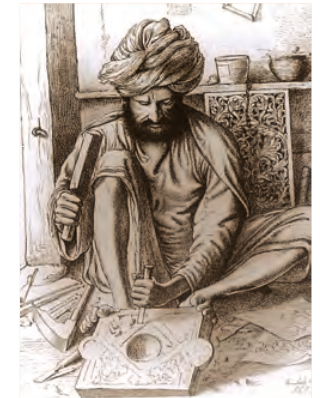

Fig. 3

A wood carver.

Taxes on markets

The following is a summary from a tenth-century inscription from Rajasthan, which lists the dues that were to be collected by temple authorities:

There were taxes in kind on:

Sugar and jaggery, dyes, thread, and cotton,

On coconuts, salt, areca nuts, butter, sesame oil,

On cloth.

Besides, there were taxes on traders, on those who sold metal goods, on distillers, on oil, on cattle fodder, and on loads of grain.

Some of these taxes were collected in kind, while others were collected in cash.

Find out more about present-day taxes on markets: who collects these, how are they collected and what are they used for.

Traders Big and Small

There were many kinds of traders. These included the Banjaras (see also Chapter 7). Several traders, especially horse traders, formed associations, with headmen who negotiated on their behalf with warriors who bought horses.

Since traders had to pass through many kingdoms and forests, they usually travelled in caravans and formed guilds to protect their interests. There were several such guilds in south India from the eighth century onwards – the most famous being the Manigramam and Nanadesi. These guilds traded extensively both within the peninsula and with Southeast Asia and China.

There were also communities like the Chettiars and the Marwari Oswal who went on to become the principal trading groups of the country. Gujarati traders, including the communities of Hindu Baniyas and Muslim Bohras, traded extensively with the ports of the Red Sea, Persian Gulf, East Africa, Southeast Asia and China. They sold textiles and spices in these ports and, in exchange, brought gold and ivory from Africa; and spices, tin, Chinese blue pottery and silver from Southeast Asia and China.

As you can see, during this period there was a great circulation of people and goods. What impact do you think this would have had on the lives of people in towns and villages?

Make a list of artisans living in towns.

The towns on the west coast were home to Arab, Persian, Chinese, Jewish and Syrian Christian traders. Indian spices and cloth sold in the Red Sea ports were purchased by Italian traders and eventually reached European markets, fetching very high profits. Spices grown in tropical climates (pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, dried ginger, etc.) became an important part of European cooking, and cotton cloth was very attractive. This eventually drew European traders to India. We will shortly read about how this changed the face of trading and towns.

Kabul

Crafts in Towns

The craftspersons of Bidar were so famed for their inlay work in copper and silver that it came to be called Bidri. The Panchalas or Vishwakarma community, consisting of goldsmiths, bronzesmiths, blacksmiths, masons and carpenters, were essential to the building of temples. They also played an important role in the construction of palaces, big buildings, tanks and reservoirs. Similarly, weavers such as the Saliyar or Kaikkolars emerged as prosperous communities, making donations to temples. Some aspects of cloth making like cotton cleaning, spinning and dyeing became specialised and independent crafts.

Fig. 4

A shawl border.

Fig. 5

A seventeenth-century candlestand; brass with black overlay.

The changing fortunes of towns

A Closer Look: Hampi, Masulipatnam and Surat

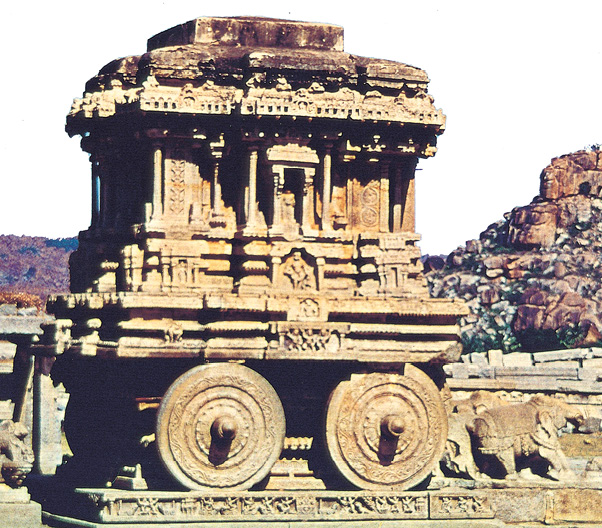

The Architectural Splendour of Hampi

Hampi is located in the Krishna-Tungabhadra basin, which formed the nucleus of the Vijayanagara Empire, founded in 1336. The magnificent ruins at Hampi reveal a well-fortified city. No mortar or cementing agent was used in the construction of these walls and the technique followed was to wedge them together by interlocking.

Fig. 6

A view of the watch-tower through a broken wall of the enclosure of Hampi.

A fortified city

This is how a Portuguese traveller, Domingo Paes, described Hampi in the sixteenth century:

… at the entrance of the gate where those pass who come from Goa, this king has made within it a very strong city fortified with walls and towers; these walls are not like those of other cities, but are made of very strong masonry such as would be found in few other parts, and inside very beautiful rows of buildings made after their manner with flat roofs.

Why do you think the city was fortified?

The architecture of Hampi was distinctive. The buildings in the royal complex had splendid arches, domes and pillared halls with niches for holding sculptures. They also had well-planned orchards and pleasure gardens with sculptural motifs such as the lotus and corbels. In its heyday in the fifteenth-sixteenth centuries, Hampi bustled with commercial and cultural activities. Muslim merchants, Chettis and agents of European traders such as the Portuguese, thronged the markets of Hampi.

During their rule, the Vijaynagara rulers took keen interest in building tanks and canals. The Anantraj Sagar Tank was built with a 1.37 km. long earthern dam across the Maldevi river. Krishnadeva Raya built a huge stone embankment between two hills to create a massive lake near Vijayanagara, from which water was carried through aqueducts and channels to irrigate fields and gardens.

Temples were the hub of cultural activities and devadasis (temple dancers) performed before the deity, royalty and masses in the many-pillared halls in the Virupaksha (a form of Shiva) temple. The Mahanavami festival, known today as Navaratri in the south, was one of the most important festivals celebrated at Hampi. Archaeologists have found the Mahanavami platform where the king received guests and accepted tribute from subordinate chiefs. From here he also watched dance and music performances as well as wrestling bouts.

Fig. 7

Stone chariot, Vitthala temple, Hampi.

Hampi fell into ruin following the defeat of Vijayanagara in 1565 by the Deccani Sultans – the rulers of Golconda, Bijapur, Ahmadnagar, Berar and Bidar.

A Gateway to the West: Surat

Surat in Gujarat was the emporium of western trade during the Mughal period along with Cambay (present-day Khambat) and somewhat later, Ahmedabad. Surat was the gateway for trade with West Asia via the Gulf of Ormuz. Surat has also been called the gate to Mecca because many pilgrim ships set sail from here.

The city was cosmopolitan and people of all castes and creeds lived there. In the seventeenth century the Portuguese, Dutch and English had their factories and warehouses at Surat. According to the English chronicler Ovington who wrote an account of the port in 1689, on average a hundred ships of different countries could be found anchored at the port at any given time.

Emporium

A place where goods from diverse production centres are bought and sold.

There were also several retail and wholesale shops selling cotton textiles. The textiles of Surat were famous for their gold lace borders (zari) and had a market in West Asia, Africa and Europe. The state built numerous rest-houses to take care of the needs of people from all over the world who came to the city. There were magnificent buildings and innumerable pleasure parks. The Kathiawad seths or mahajans (moneychangers) had huge banking houses at Surat. It is noteworthy that the Surat hundis were honoured in the far-off markets of Cairo in Egypt, Basra in Iraq and Antwerp in Belgium.

However, Surat began to decline towards the end of the seventeenth century. This was because of many factors: the loss of markets and productivity because of the decline of the Mughal Empire, control of the sea routes by the Portuguese and competition from Bombay (present-day Mumbai) where the English East India Company shifted its headquarters in 1668. Today, Surat is a bustling commercial centre.

Fishing in Troubled Waters: Masulipatnam

The town of Masulipatnam or Machlipatnam (literally, fish port town) lay on the delta of the Krishna river. In the seventeenth century it was a centre of intense activity.

A poor fisher town

This is a description of Masulipatnam by William Methwold, a Factorof the English East India Company, in 1620:

This is the chief port of Golconda, where the Right Worshipfull East India Company have their Agent. It is a small town but populous, unwalled, ill built and worse situated; within all the springs are brackish. It was first a poor fisher town … afterwards, the convenience of the road (a place where ships can anchor) made it a residence for merchants and so continues since our and the Dutch nation frequented this coast.

Why did the English and the Dutch decide to establish settlements in Masulipatnam?

Factor

Official in-charge of trading activities of the European Trading Companies.

The Qutb Shahi rulers of Golconda imposed royal monopolies on the sale of textiles, spices and other items to prevent the trade passing completely into the hands of the various East India Companies. Fierce competition among various trading groups – the Golconda nobles, Persian merchants, Telugu Komati Chettis, and European traders – made the city populous and prosperous. As the Mughals began to extend their power to Golconda their representative, the governor Mir Jumla who was also a merchant, began to play off the Dutch and the English against each other. In 1686-1687 Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb annexed Golconda.

This caused the European Companies to look for alternatives. It was a part of the new policy of the English East India Company that it was not enough if a port had connections with the production centres of the hinterland. The new Company trade centres, it was felt, should combine political, administrative and commercial roles. As the Company traders moved to Bombay, Calcutta (present-day Kolkata) and Madras (present-day Chennai), Masulipatnam lost both its merchants and prosperity and declined in the course of the eighteenth century, being today nothing more than a dilapidated little town.

New Towns and Traders

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, European countries were searching for spices and textiles, which had become popular both in Europe and West Asia. The English, Dutch and French formed East India Companies in order to expand their commercial activities in the east. Initially great Indian traders like Mulla Abdul Ghafur and Virji Vora who owned a large number of ships competed with them. However, the European Companies used their naval power to gain control of the sea trade and forced Indian traders to work as their agents. Ultimately, the English emerged as the most successful commercial and political power in the subcontinent.

The spurt in demand for goods like textiles led to a great expansion of the crafts of spinning, weaving, bleaching, dyeing, etc. with more and more people taking them up. Indian textile designs became increasingly refined. However, this period also saw the decline of the independence of craftspersons. They now began to work on a system of advances which meant that they had to weave cloth which was already promised to European agents. Weavers no longer had the liberty of selling their own cloth or weaving their own patterns. They had to reproduce the designs supplied to them by the Company agents.

The eighteenth century saw the rise of Bombay, Calcutta and Madras, which are nodal cities today. Crafts and commerce underwent major changes as merchants and artisans (such as weavers) were moved into the Black Towns established by the European companies within these new cities. The “blacks” or native traders and craftspersons were confined here while the “white” rulers occupied the superior residencies of Fort St. George in Madras or Fort St. William in Calcutta. The story of crafts and commerce in the eighteenth century will be taken up next year.

Fig. 8

A Bombay street, early nineteenth century.

ELSEWHERE

Vasco da Gama and Christopher Columbus

In the fifteenth century European sailors undertook unprecedented explorations of sea routes. They were driven by the desire to find ways of reaching the Indian subcontinent and obtaining spices.

Vasco da Gama, a Portuguese sailor, sailed down the African Coast, went round the Cape of Good Hope and crossed over to the Indian Ocean . His first journey took more than a year; he reached Calicut in 1498, and returned to Lisbon, the capital of Portugal, the following year. He lost two of his four ships, and of the 170 men at the start of the journey, only 54 survived. In spite of the obvious hazards, the routes that were opened up proved to be extremely profitable – and he was followed by English, Dutch and French sailors.

Fig. 9

Vasco da Gama.

The search for sea routes to India had another, unexpected fallout. On the assumption that the earth was round, Christopher Columbus, an Italian, decided to sail westwards across the Atlantic Ocean to find a route to India. He landed in the West Indies (which got their name because of this confusion) in 1492. He was followed by sailors and conquerors from Spain and Portugal, who occupied large parts of Central and South America, often destroying earlier settlements in the area.

Imagine

Imagine

You are planning a journey from Surat to West Asia in the seventeenth century. What are the arrangements you will make?

Let’s recall

1. Fill in the blanks:

(a) The Rajarajeshvara temple was built in ———.

(b) Ajmer is associated with the Sufi saint ————.

(c) Hampi was the capital of the ———— Empire.

(d) The Dutch established a settlement at ———— in Andhra Pradesh.

2. State whether true or false:

(a) We know the name of the architect of the Rajarajeshvara temple from an inscription.

(b) Merchants preferred to travel individually rather than in caravans.

(c) Kabul was a major centre for trade in elephants.

(d) Surat was an important trading port on the Bay of Bengal.

3. How was water supplied to the city of Thanjavur?

4. Who lived in the “Black Towns” in cities such as Madras?

Let’s understand

5. Why do you think towns grew around temples?

6. How important were craftspersons for the building and maintenance of temples?

7. Why did people from distant lands visit Surat?

8. In what ways was craft production in cities like Calcutta different from that in cities like Thanjavur?

Let’s discuss

9. Compare any one of the cities described in this chapter with a town or a village with which you are familiar. Do you notice any similarities or differences?

10. What were the problems encountered by merchants? Do you think some of these problems persist today?

Let’s do

11. Find out more about the architecture of either Thanjavur or Hampi, and prepare a scrap book illustrating temples and other buildings from these cities.

12. Find out about any present-day pilgrimage centre. Why do you think people go there? What do they do there? Are there any shops in the area? If so, what is bought and sold there?