Table of Contents

UNIT THREE

Gender

Teacher’s note

Gender is a term that you may often have heard. It is a term, however, that is not easily understood. It tends to remain distant from our lives and restricted to discussions during training programmes. In fact, it is something that all of us experience in our lives on a daily basis. It determines, for example, who we are and what we will become, where we can go and where not, the life choices available to us and those we eventually make. Our understanding of gender is often based on the family and society that we live in. This leads us to think that the roles we see men and women around us play are fixed and natural. In fact, these roles differ across communities around the world. By gender, then, we mean the many social values and stereotypes our cultures attach to the biological distinction ‘male’ and ‘female’. It is a term that helps us to understand many of the inequalities and power relations between men and women in society.

The following two chapters explore the concept of gender without actually using the term. Instead, through different pedagogic tools like case studies, stories, classroom activities, data analysis and photographs, students are encouraged to question and think about their own lives and the society around them. Gender is often mistakenly thought to be something that concerns women or girls alone. Thus, care has been taken in these chapters to draw boys into the discussion as well.

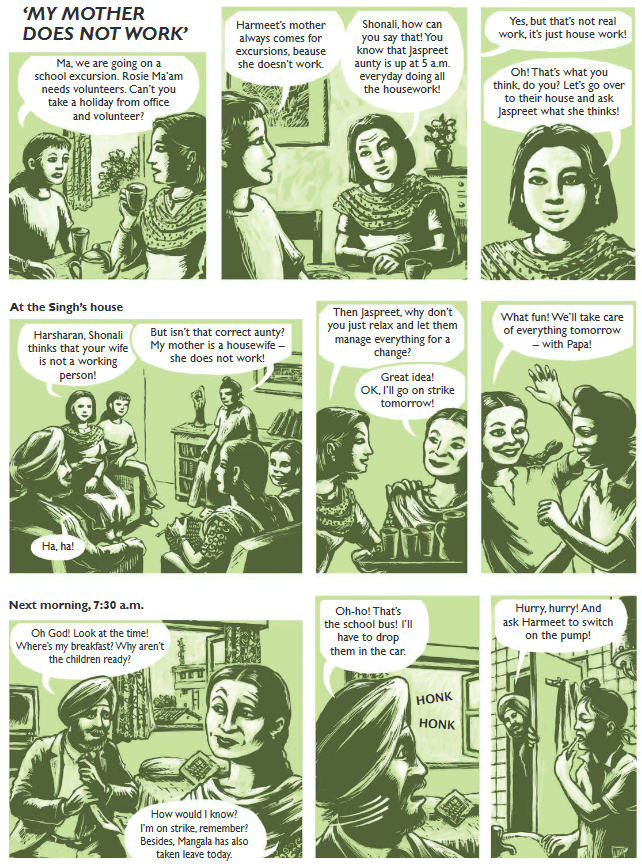

Chapter 4 uses two case studies, situated in different places and points in time to show how girls and boys are brought up or socialised differently. This enables them to understand that the process of socialisation is not uniform; instead it is socially determined and changes continuously over time. The chapter also addresses the fact that societies assign different values to the roles men and women play and the work they do, which becomes a basis for inequality and discrimination. Through a storyboard, students discuss the issue of housework. Done primarily by women, housework is often not considered ‘work’ and, therefore made invisible and devalued.

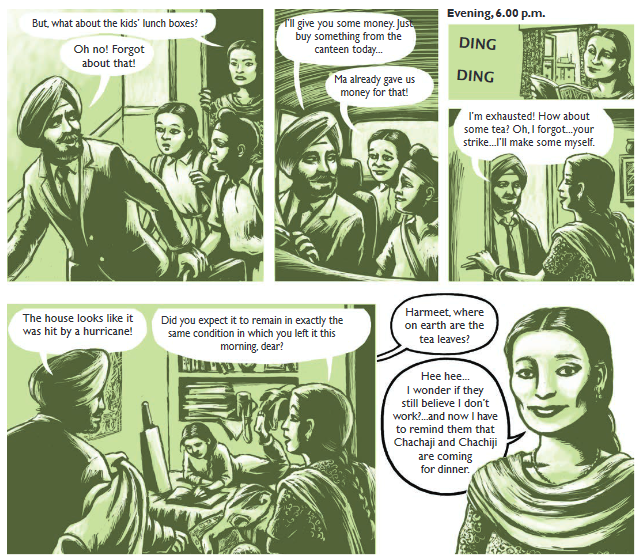

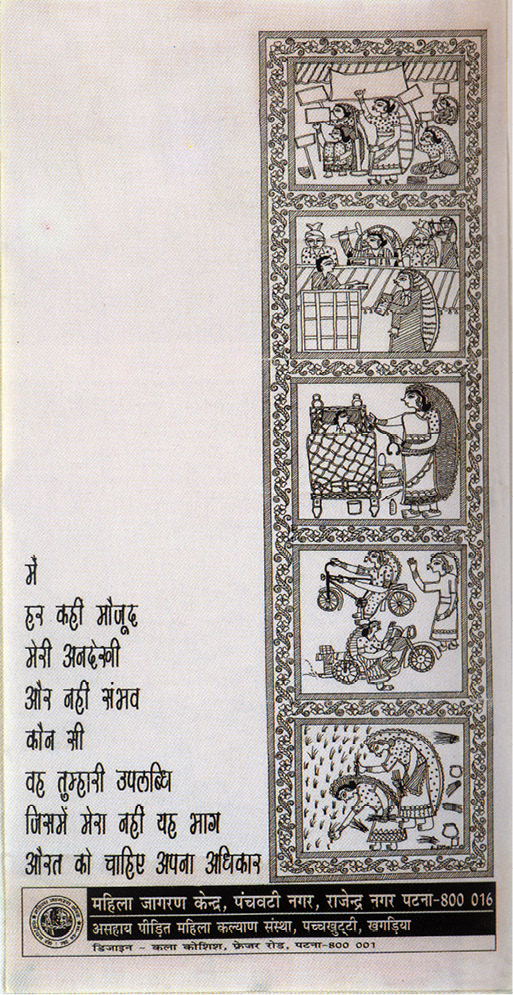

Chapter 5 further develops ideas around gender inequalities in the world of work and describes women’s struggles for equality. Through a classroom activity, students begin questioning existing stereotypes regarding work and career choices. The chapter also points out that opportunities like education are not equally available to boys and girls. By reading about the lives of two Indian women, from the ninteenth and twentieth centuries, students see how women struggled to change their lives by learning to read and write. Change on a large scale usually takes place through collective struggles. The chapter concludes with a photo-essay that gives examples of different strategies the women’s movement has used to fight for change.

CHAPTER 4

Growing up as Boys and Girls

Being a boy or a girl is an important part of one’s identity. The society we grow up in teaches us what kind of behaviour is acceptable for girls and boys, what boys and girls can or cannot do. We often grow up thinking that these things are exactly the same everywhere. But do all societies look at boys and girls in the same way? We will try and answer this question in this chapter. We will also look at how the different roles assigned to boys and girls prepare them for their future roles as men and women. We will learn that most societies value men and women differently. The roles women play and the work they do are usually valued less than the roles men play and the work they do. This chapter will also examine how inequalities between men and women emerge in the area of work.

Growing up in Samoa in the 1920s

The Samoan Islands are part of a large group of small islands in the southern part of the Pacific Ocean. In the 1920s, according to research reports on Samoan society, children did not go to school. They learnt many things, such as how to take care of children or do household work from older children and from adults. Fishing was a very important activity on the islands. Young people, therefore, learnt to undertake long fishing expeditions. But they learnt these things at different points in their childhood.

A Class VII Samoan child in his school uniform.

In what ways do the experiences of Samoan children and teenagers differ from your own experiences of growing up? Is there anything in this experience that you wish was part of your growing up?

As soon as babies could walk, their mothers or other adults no longer looked after them. Older children, often as young as five years old, took over this responsibility. Both boys and girls looked after their younger siblings. But, by the time a boy was about nine years old, he joined the older boys in learning outdoor jobs like fishing and planting coconuts. Girls had to continue looking after small children or do errands for adults till they were teenagers. But, once they became teenagers they had much more freedom. After the age of fourteen or so, girls also went on fishing trips, worked in the plantations, learnt how to weave baskets. Cooking was done in special cooking-houses, where boys were supposed to do most of the work while girls helped with the preparations.

Why do girls like to go to school together in groups?

Growing up male in Madhya Pradesh in the 1960s

The following is adapted from an account of experiences of being in a small town in Madhya Pradesh in the 1960s.

From Class VI onwards, boys and girls went to separate schools. The girls’ school was designed very differently from the boys’ school. They had a central courtyard where they played in total seclusion and safety from the outside world. The boys’ school had no such courtyard and our playground was just a big space attached to the school. Every evening, once school was over, the boys watched as hundreds of school girls crowded the narrow streets. As these girls walked on the streets, they looked so purposeful. This was unlike the boys who used the streets as a place to stand around idling, to play, to try out tricks with their bicycles. For the girls, the street was simply a place to get straight home. The girls always went in groups, perhaps because they also carried fears of being teased or attacked.

Make a drawing of a street or a park in your neighbourhood. Show the different kinds of activities young boys and girls may be engaged in. You could do this individually or in groups.

Are there as many girls as boys in your drawing? Most probably you would have drawn fewer girls. Can you think of reasons why there are fewer women and girls in your neighbourhood streets, parks and markets in the late evenings or at night?

Are girls and boys doing different activities? Can you think of reasons why this might be so? What would happen if you replaced the girls with the boys and vice-versa?

After reading the two examples above, we realise that there are many different ways of growing up. Often we think that there is only one way in which children grow up. This is because we are most familiar with our own experiences. If we talk to elders in our family, we will see that their childhoods were probably very different from ours.

We also realise that societies make clear distinctions between boys and girls. This begins from a very young age. We are for example, given different toys to play with. Boys are usually given cars to play with and girls dolls. Both toys can be a lot of fun to play with. Why are girls then given dolls and boys cars? Toys become a way of telling children that they will have different futures when they become men and women. If we think about it, this difference is created in the smallest and most everyday things. How girls must dress, what games boys should play, how girls need to talk softly or boys need to be tough. All these are ways of telling children that they have specific roles to play when they grow up to be men and women. Later in life this affects the subjects we can study or the careers we can choose.

In most societies, including our own, the roles men and women play or the work they do, are not valued equally. Men and women do not have the same status. Let us look at how this difference exists in the work done by men and women.

Valuing housework

Harmeet’s family did not think that the work Jaspreet did within the house was real work. This feeling is not unique to their families. Across the world, the main responsibility for housework and care-giving tasks, like looking after the family, especially children, the elderly and sick members, lies with women. Yet, as we have seen, the work that women do within the home is not recognised as work. It is also assumed that this is something that comes naturally to women. It, therefore, does not have to be paid for. And society devalues this work.

Lives of domestic workers

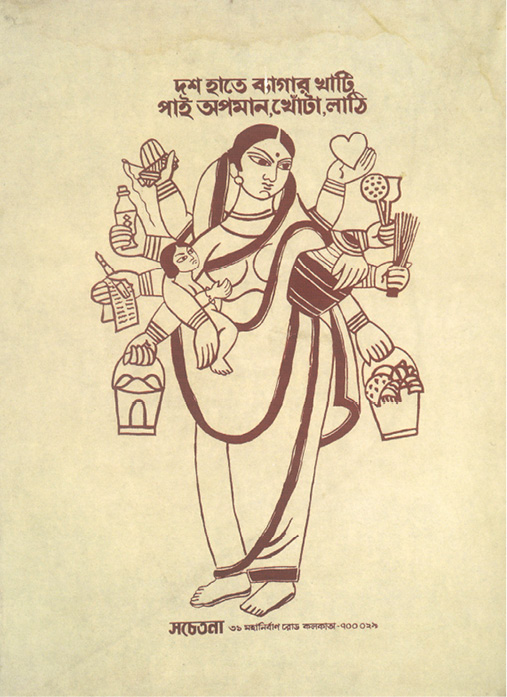

Melani with her daughter.

In the story above, Harmeet’s mother was not the only one who did the housework. A lot of the work was done by Mangala, their domestic helper. Many homes, particularly in towns and cities, employ domestic workers. They do a lot of work – sweeping and cleaning, washing clothes and dishes, cooking, looking after young children or the elderly. Most domestic workers are women. Sometimes, even young boys or girls are employed to do this work. Wages are low, as domestic work does not have much value. A domestic worker’s day can begin as early as five in the morning and end as late as twelve at night! Despite the hard work they do, their employers often do not show them much respect. This is what Melani, a domestic worker had to say about her experience of working in Delhi – “My first job was with a rich family that lived in a three-storeyed house. The memsahib was very strange as she would shout to get any work done. My work was in the kitchen. There were two other girls who did the cleaning. Our day would begin at 5 o’clock. For breakfast we would get a cup of tea and two dry rotis. We could never get a third roti. In the evening, when I cooked the food, the two other girls would beg me to give them an extra roti. I would secretly give it to them and make an extra one for myself. We were so hungry after working through the day! We could not wear chappals in the house. In the winter, our feet would swell up with the cold. I used to feel scared of the memsahib but also felt angry and humiliated. Did we not work all day? Did we not deserve to be treated with some respect?”

Were Harmeet and Shonali correct in saying that Harmeet’s mother did not work?

What do you think would happen if your mother or those involved in doing the work at home went on a strike for a day?

Why do you think that men and boys generally do not do housework? Do you think they should?

In fact, what we commonly term as housework actually involves many different tasks. A number of these tasks require heavy physical work. In both rural and urban areas women and girls have to fetch water. In rural areas women and girls carry heavy headloads of firewood. Tasks like washing clothes, cleaning, sweeping and picking up loads require bending, lifting and carrying. Many chores, like cooking, involve standing for long hours in front of hot stoves. The work women do is strenuous and physically demanding — words that we normally associate with men.

Another aspect of housework and care-giving that we do not recognise is that it is very time consuming. In fact, if we add up the housework and the work, women do outside the home, we find that women spend much more time working than men and have much less time for leisure.

Below is some data from a special study done by the Central Statistical Organization of India (1998-1999). See if you can fill in the blanks.

What are the total number of work hours spent by women in Haryana and Tamil Nadu each week?

How does this compare with the total number of work hours spent by men?

Many women like Shonali’s mother in the story and the women in Tamil Nadu and Haryana who were surveyed work both inside and outside the home. This is often referred to as the double burden of women’s work.

Women’s work and equality

As we have seen the low value attached to women’s household and care-giving work is not an individual or family matter. It is part of a larger system of inequality between men and women. It, therefore, has to be dealt with through actions not just at the level of the individual or the family but also by the government. As we now know, equality is an important principle of our Constitution. The Constitution says that being male or female should not become a reason for discrimination. In reality, inequality between the sexes exists. The government is, therefore, committed to understanding the reasons for this and taking positive steps to remedy the situation. For example, it recognises that burden of child-care and housework falls on women and girls. This naturally has an impact on whether girls can attend school. It determines whether women can work outside the house and what kind of jobs and careers they can have. The government has set up anganwadis or child-care centres in several villages in the country. The government has passed laws that make it mandatory for organisations that have more than 30 women employees to provide crèche facilities. The provision of crèches helps many women to take up employment outside the home. It also makes it possible for more girls to attend schools.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) www.in.undp.org

This poster was created by a women’s group in Bengal. Can you write an interesting slogan for the poster?

EXERCISES

1. Are the statements given alongside true or false. Support your answer with the use of an example –

2. Housework is invisible and unpaid work.

Housework is physically demanding.

Housework is time consuming.

Write in your own words what is meant by the terms ‘invisible’, ‘physically demanding’, and ‘time consuming’? Give one example of each based on the household tasks undertaken by women in your home.

3. Make a list of toys and games that boys typically play and another for girls. If there is a difference between the two lists, can you think of some reasons why this is so? Does this have any relationship to the roles children have to play as adults?

4. If you have someone working as a domestic help in your house or locality talk to her and find out a little bit more about her life – Who are her family members? Where is her home? How many hours does she work? How much does she get paid? Write a small story based on these details.

a. All societies do not think similarly about the roles that boys and girls play.

b. Our society does not make distinctions between boys and girls when they are growing up.

c. Women who stay at home do not work.

d. The work that women do is less valued than that of men.

Glossary

Identity: Identity is a sense of self-awareness of who one is. Typically, a person can have several identities. For example, a person can be a girl, a sister and a musician.

Double-burden: Literally means a double load. This term is commonly used to describe the women’s work situation. It has emerged from a recognition that women typically labour both inside the home (housework) and outside.

Care-giving: Care-giving refers to a range of tasks related to looking after and nurturing. Besides physical tasks, they also involve a strong emotional aspect.

De-valued: When someone is not given due recognition for a task or job they have done, they can feel de-valued. For example, if a boy has put in a lot of effort into making a special birthday gift for his friend and this friend does not say anything about this, then the boy may feel de-valued.