Table of Contents

CHAPTER 5

Women Change the World

In the previous chapter, we saw how women’s work in the home is not recognised as work. We also read how doing household work and taking care of family members is a full time job and there are no specific hours at which it begins or ends. In this chapter, we will look at work outside the home, and understand how some occupations are seen to be more suitable for men than for women. We will also learn about how women struggle for equality. Getting an education was, and still is, one way in which new opportunities were created for women. This chapter will also briefly trace the different types of efforts made by the women’s movement to challenge discrimination in more recent years.

Who does what work?

Draw images of the following –

A farmer

A factory worker

A nurse

A scientist

A pilot

A teacher

See what images your class drew by filling in the table below. Add up the number of male and female images separately for each occupation.

| Category | Male image | Female image |

| Teacher | ||

| Farmer | ||

| Factory worker | ||

| Nurse | ||

| Scientist | ||

| Pilot |

Are there more images of men than women?

In what kinds of jobs were there more images of men than women?

Have all the nurses been drawn as females? Why?

Are there fewer images of female farmers? If so, why?

How does your class exercise compare with Rosie Ma’am’s class exercise?

83.6 per cent of working women in India are engaged in agricultural work. Their work includes planting, weeding, harvesting and threshing. Yet, when we think of a farmer we only think of a man.

Source: NSS 61st Round (2004-05)

Rosie Ma’am’s class has 30 children. She did the same exercise in her class and here is the result.

| Category | Male image | Female image |

| Teacher | 5 | 25 |

| Farmer | 30 | 0 |

| Factory worker | 25 | 5 |

| Nurse | 0 | 30 |

| Scientist | 25 | 5 |

| Pilot | 27 | 3 |

Fewer opportunities and rigid expectations

A lot of the children in Rosie Ma’am’s class drew women as nurses and men as army officers. The reason they did this is because they feel that outside the home too, women are good at only certain jobs. For example, many people believe that women make better nurses because they are more patient and gentle. This is linked to women’s roles within the family. Similarly, it is believed that science requires a technical mind and girls and women are not capable of dealing with technical things.

Because so many people believe in these stereotypes, many girls do not get the same support that boys do to study and train to become doctors and engineers. In most families, once girls finish school, they are encouraged by their families to see marriage as their main aim in life.

Breaking stereotypes

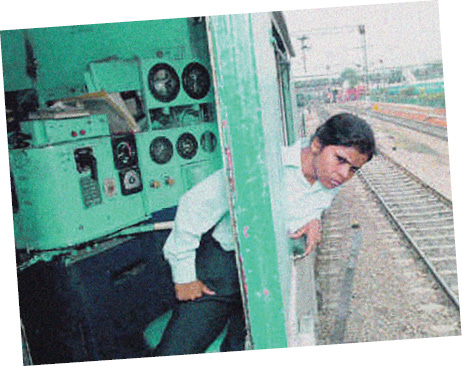

Engine drivers are men. But 27-year-old Laxmi Lakra, from a poor tribal family in Jharkhand has begun to change things. She is the first woman engine driver for Northern Railways.

Laxmi’s parents are not literate but they struggled and overcame many hardships to make sure their children got an education. Laxmi studied in a government school. Even in school, Laxmi helped with the housework and did odd jobs. She studied hard and did well and then went on to get a diploma in electronics. She then took the railway board exam and passed it on her first attempt.

Laxmi says, “I love challenges and the moment somebody says it is not for girls, I make sure I go ahead and do it.” Laxmi has had to do this several times in her life – when she wanted to take electronics; when she rode motorcycles at the polytechnic; and when she decided to become an engine driver.

Her philosophy is simple – “As long as I am having fun without harming anyone, as long as I am doing well and helping my parents, why should I not lead a lifestyle of my choice?”

(Adapted from Driving Her Train by Neeta Lal, Women’s Features Service)

It is important to understand that we live in a society in which all children face pressures from the world around them. Sometimes, these come in the form of demands from adults. At other times, they can just be because of unfair teasing by our own friends. Boys are pressurised to think about getting a job that will pay a good salary. They are also teased and bullied if they do not behave like other boys. You may remember that in your Class VI book you read about how boys at an early age are encouraged not to cry in front of others.

Read the story below and answer the questions –

If you were Xavier, what subject would you choose and why?

In your experience, what are some of the other pressures that boys experience?

Ramabai (1858–1922), shown above with her daughter, championed the cause of women’s education. She never went to school but learnt to read and write from her parents. She was given the title ‘Pandita’ because she could read and write Sanskrit, a remarkable achievement as women then were not allowed such knowledge. She went on to set up a Mission in Khedgaon near Pune in 1898, where widows and poor women were encouraged not only to become literate but to be independent. They were taught a variety of skills from carpentry to running a printing press, skills that are not usually taught to girls even today. The printing press can be seen in the picture on the top left corner. Ramabai’s Mission is still active today.

Learning for change

Going to school is an extremely important part of your life. As more and more children enter school every year, we begin to think that it is normal for all children to go to school. Today, it is difficult for us to imagine that school and learning could be seen as “out of bounds” or not appropriate for some children. But in the past, the skill of reading and writing was known to only a few. Most children learnt the work their families or elders did. For girls, the situation was worse. In communities that taught sons to read and write, daughters were not allowed to learn the alphabet. Even in families where skills like pottery, weaving and craft were taught, the contribution of daughters and women was only seen as supportive. For example, in the pottery trade, women collected the mud and prepared the earth for the pots. But since they did not operate the wheel, they were not seen as potters.

In the nineteenth century, many new ideas about education and learning emerged. Schools became more common and communities that had never learnt reading and writing started sending their children to school. But there was a lot of opposition to educating girls even then. Yet many women and men made efforts to open schools for girls. Women struggled to learn to read and write.

Let us read about the experience of Rashsundari Devi (1800–1890), who was born in West Bengal, some 200 years ago. At the age of 60, she wrote her autobiography in Bangla. Her book titled Amar Jiban is the first known autobiography written by an Indian woman. Rashsundari Devi was a housewife from a rich landlord’s family. At that time, it was believed that if a woman learnt to read and write, she would bring bad luck to her husband and become a widow! Despite this, she taught herself how to read and write in secret, well after her marriage.

Learning to read and write led some women to question the situation of women in society. They wrote stories, letters and autobiographies describing their own experiences of inequality. In their writings, they also imagined new ways of thinking and living for both

men and women.

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain and her dreams about ‘Ladyland’

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880–1932) was born into a rich family who owned a lot of land. Though she knew how to read and write Urdu, she was stopped from learning Bangla and English. In those days, English was seen as a language that would expose girls to new ideas, which people thought were not correct for them. Therefore, it was mostly boys who were taught English. Rokeya learnt to read and write Bangla and English with the support of her elder brother and an elder sister. She went on to become a writer. She wrote a remarkable story titled Sultana’s Dream in 1905 to practise her English skills when she was merely 25 years old. This story imagined a woman called Sultana who reaches a place called Ladyland. Ladyland is a place where women had the freedom to study, work, and create inventions like controlling rain from the clouds and flying air cars. In this Ladyland, the men had been sent into seclusion – their aggressive guns and other weapons of war defeated by the brain-power of women. As Sultana travels in Ladyland with Sister Sarah, she awakes to realise that she was only dreaming.

As you can see, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain was dreaming of women flying planes and cars even before girls were being allowed to go to school! This was the way in which education and learning had changed Rokeya’s own life. Rokeya did not stop at getting education just for herself. Her education gave her the power not only to dream and write, but also to do more – to help other girls go to school and to build their own dreams. In 1910, she started a school for girls in Kolkata, and to this day, the school is still functioning.

“I would start working at dawn, and I would still be at it until well beyond midnight. I had no rest in between. I was only fourteen years old at the time. I came to nurture a great longing: I would learn to read and I would read a religious manuscript. I was unlucky, in those days women were not educated. Later, I began to resent my own thoughts. What is wrong with me? Women do not read, how will I do it? Then I had a dream: I was reading the manuscript of Chaitanya Bhagabat (the life of a saint)… Later in the day, as I sat cooking in the kitchen, I heard my husband say to my eldest son: “Bepin, I have left my Chaitanya Bhagabat here. When I ask for it, bring it in.” He left the book there and went away. When the book had been taken inside, I secretly took out a page and hid it carefully. It was a job hiding it, for nobody must find it in my hands. My eldest son was practising his alphabets at that time. I hid one of them as well. At times, I went over that, trying to match letters from that page with the letters that I remembered. I also tried to match the words with those that I would hear in the course of my days. With tremendous care and effort, and over a long period of time, I learnt how to read…”

Unlike Rashsundari Devi and Rokeya Hossain, who were not allowed to learn to read and write, large numbers of girls attend school in India today. Despite this, there continue to be many girls who leave school for reasons of poverty, inadequate schooling facilities and discrimination. Providing equal schooling facilities to children from all communities and class backgrounds, and particularly girls, continues to be a challenge in India.

After learning the alphabet, Rashsundari Devi was able to read the Chaitanya Bhagabat. Through her own writing she also gave the world an opportunity to read about women’s lives in those days. Rashsundari Devi wrote about her everyday life experiences in details. There were days when she did not have a moment’s rest, no time even to sit down and eat!

Schooling and education today

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) www.in.undp.org

Today, both boys and girls attend school in large numbers. Yet, as we will see, there still remain differences between the education of boys and girls. India has a census every 10 years, which counts the whole population of the country. It also gathers detailed information about the people living in

India – their age, schooling, what work they do, and so on. We use this information to measure many things, like the number of literate people, and the ratio of men and women. According to the 1961 census, about 40 per cent of all boys and men

(7 years old and above) were literate (that is, they could at least write their names) compared to just 15 per cent of all girls and women. In the most recent census of 2011, these figures have grown to 82 per cent for boys and men, and 65 per cent for girls and women. This means that the proportion of both men and women who are now able to read and have at least some amount of schooling has increased. But, as you can also see, the percentage of the male group is still higher than the female group. The gap has not gone away.

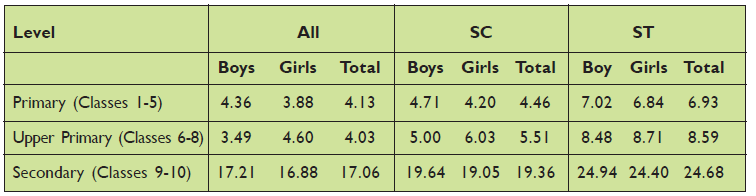

Here is a table that shows the percentage of girls and boys who leave schools from different social groups including Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST).

Average Annual Drop-out Rate in School Education (2014–15)

(in percentage)

Source: Educational Statistics at a Glance, MHRD, 2018

You have probably noticed in the above table that SC and ST girls leave school at a rate that is higher than the category ‘All Girls’. This means that girls who are from Dalit (SC) and Adivasi (ST) backgrounds are less likely to remain in school. The 2011 census also found that Muslim girls are less likely, than SC and ST girls, to complete primary school. While a Muslim girl is likely to stay in school for around three years, girls from other communities spend around four years in school.

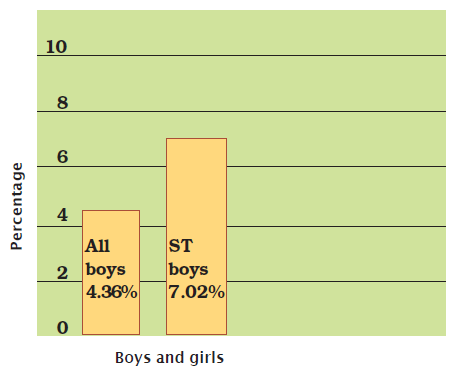

Average Annual Drop-out Rate in School Education (2014–15)

What percentage of children leave school at the upper primary level?

At which level of education do you see the highest percentage of children leaving?

Why do you think that the percentage of Adivasi girls and boys leaving school is higher than that of any other group?

There are several reasons why children from Dalit, Adivasi and Muslim communities leave school. In many parts of the country, especially in rural and poor areas, there may not even be proper schools nor teachers who teach on a regular basis. If a school is not close to people’s homes, and there is no transport like buses or vans, parents may not be willing to send their girls to school. Many families are too poor and unable to bear the cost of educating all their children. Boys may get preference in this situation. Many children also leave school because they are discriminated against by their teacher and classmates, just like Omprakash Valmiki was.

Find out about the ‘Beti Bachao Beti Padhao’ campaign launched in 2014.

From the given table, convert the figures of primary class children who leave school into a bar diagram. Two percentages have already been converted for you in the bar diagram on the left.

Women’s movement

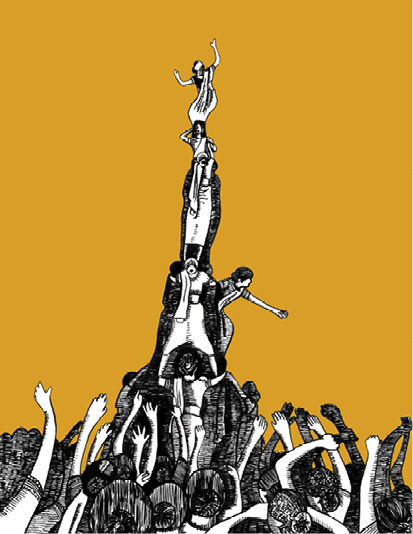

Women and girls now have the right to study and go to school. There are other spheres – like legal reform, violence and health – where the situation of women and girls has improved. These changes have not happened automatically. Women individually, and collectively have struggled to bring about these changes. This struggle is known as the Women’s Movement. Individual women and women’s organisations from different parts of the country are part of the movement. Many men support the women’s movement as well. The diversity, passion and efforts of those involved makes it a very vibrant movement. Different strategies have been used to spread awareness, fight discrimination and seek justice. Here are some glimpses of this struggle.

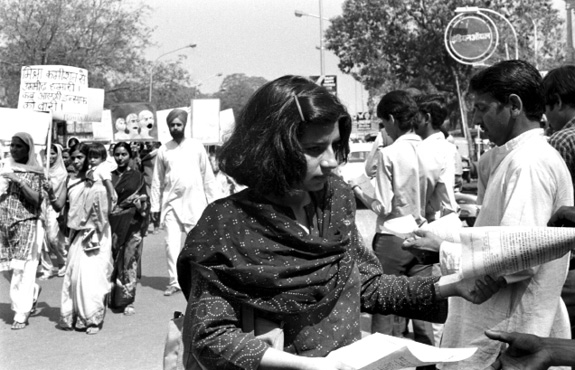

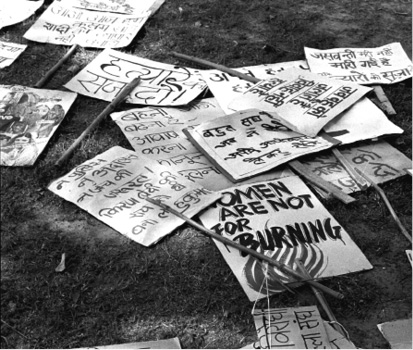

Campaigning

Campaigns to fight discrimination and violence against women are an important part of the women’s movement. Campaigns have also led to new laws being passed. A law was made in 2006 to give women who face physical and mental violence within their homes, also called domestic violence, some legal protection.

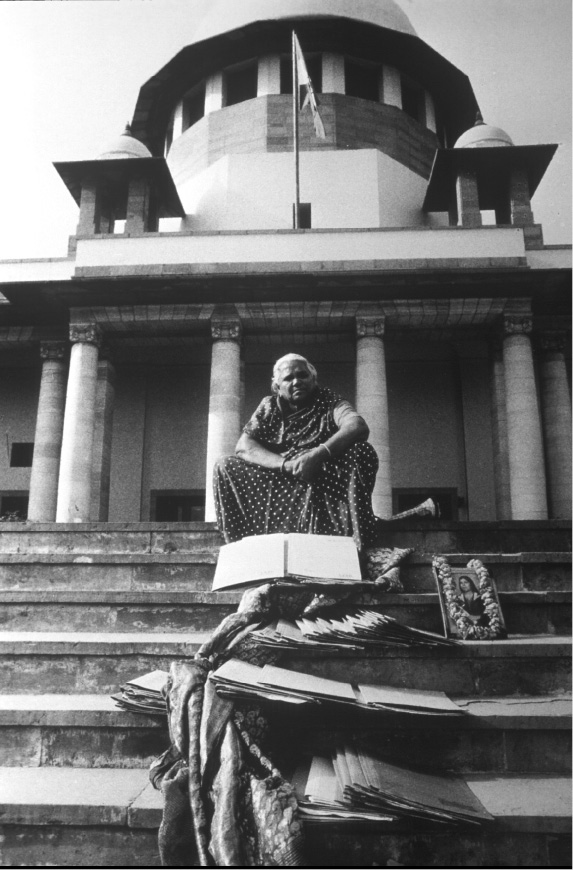

Satyarani, an active member of the women’s movement, sitting on the steps of the Supreme Court surrounded by legal files gathered during the course of a long legal battle to seek justice for her daughter who was murdered for dowry.

Similarly, efforts made by the women’s movement led the Supreme Court to formulate guidelines in 1997 to protect women against sexual harassment at the workplace and within educational institutions.

In the 1980s, for example, women’s groups across the country spoke out against ‘dowry deaths’ — cases of young brides being murdered by their in-laws or husbands, greedy for more dowry. Women’s groups spoke out against the failure to bring these cases to justice. They did so by coming on to the streets, approaching the courts, and by sharing information. Eventually, this became a public issue in the newspapers and society, and the dowry laws were changed to punish families who seek dowry.

Raising Awareness

An important part of the women’s movements’ work is to raise public awareness on women’s rights issues. Their message has been spread through street plays, songs and public meetings.

Protesting

The women’s movement raises its voice when violations against women take place or for example, when a law or policy acts against their interests. Public rallies and demonstrations are a very powerful way of drawing attention to injustices.

Showing Solidarity

The women’s movement is also about showing solidarity with other women and causes.

Below: On 8 March, International Women’s Day, women all over the world come together to celebrate and renew their struggles.

Above: Women are holding up candles to demonstrate the solidarity between the people of India and Pakistan. Every year, on 14 August, several thousand people gather at Wagah on the border of India and Pakistan and hold a cultural programme.

EXERCISES

1. How do you think stereotypes, about what women can or cannot do, affect women’s right to equality?

2. List one reason why learning the alphabet was so important to women like Rashsundari Devi, Ramabai and Rokeya.

3. “Poor girls drop out of school because they are not interested in getting an education.” Re-read the last paragraph on page 62 and explain why this statement is not true.

4. Can you describe two methods of struggle that the women’s movement used to raise issues? If you had to organise a struggle against stereotypes, about what women can or cannot do, what method would you employ from the ones that you have read about? Why would you choose this particular method?

Glossary

Stereotype: When we believe that people belonging to particular groups based on religion, wealth, language are bound to have certain fixed characteristics or can only do a certain type of work, we create a stereotype. For example, in this chapter, we saw how boys and girls are made to take certain subjects not because he or she has an aptitude for it, but because they are either boys or girls. Stereotypes prevent us from looking at people as unique individuals.

Discrimination: When we do not treat people equally or with respect we are indulging in discrimination. It happens when people or organisations act on their prejudices. Discrimination usually takes place when we treat some one differently or make a distinction.

Violation: When someone forcefully breaks the law or a rule or openly shows disrespect, we can say that he or she has committed a violation.

Sexual harassment: This refers to physical or verbal behaviour that is of a sexual nature and against the wishes of a woman.