Table of Contents

Chapter 2

Polynomials

2.1 Introduction

You have studied algebraic expressions, their addition, subtraction, multiplication and division in earlier classes. You also have studied how to factorise some algebraic expressions. You may recall the algebraic identities :

(x + y)2 = x2 + 2xy + y2

(x – y)2 = x2 – 2xy + y2

and x2 – y2 = (x + y) (x – y)

and their use in factorisation. In this chapter, we shall start our study with a particular type of algebraic expression, called polynomial, and the terminology related to it. We shall also study the Remainder Theorem and Factor Theorem and their use in the factorisation of polynomials. In addition to the above, we shall study some more algebraic identities and their use in factorisation and in evaluating some given expressions.

2.2 Polynomials in One Variable

Let us begin by recalling that a variable is denoted by a symbol that can take any real value. We use the letters x, y, z, etc. to denote variables. Notice that 2x, 3x, – x, – x are algebraic expressions. All these expressions are of the form (a constant) × x. Now suppose we want to write an expression which is (a constant) × (a variable) and we do not know what the constant is. In such cases, we write the constant as a, b, c, etc. So the expression will be ax, say.

x are algebraic expressions. All these expressions are of the form (a constant) × x. Now suppose we want to write an expression which is (a constant) × (a variable) and we do not know what the constant is. In such cases, we write the constant as a, b, c, etc. So the expression will be ax, say.

However, there is a difference between a letter denoting a constant and a letter denoting a variable. The values of the constants remain the same throughout a particular situation, that is, the values of the constants do not change in a given problem, but the value of a variable can keep changing.

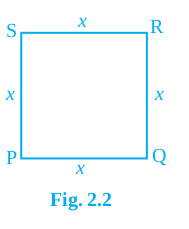

Now, consider a square of side 3 units (see Fig. 2.1). What is its perimeter? You know that the perimeter of a square is the sum of the lengths of its four sides. Here, each side is 3 units. So, its perimeter is 4 × 3, i.e., 12 units. What will be the perimeter if each side of the square is 10 units? The perimeter is 4 × 10, i.e., 40 units. In case the length of each side is x units (see Fig. 2.2), the perimeter is given by 4x units. So, as the length of the side varies, the perimeter varies.

Now, consider a square of side 3 units (see Fig. 2.1). What is its perimeter? You know that the perimeter of a square is the sum of the lengths of its four sides. Here, each side is 3 units. So, its perimeter is 4 × 3, i.e., 12 units. What will be the perimeter if each side of the square is 10 units? The perimeter is 4 × 10, i.e., 40 units. In case the length of each side is x units (see Fig. 2.2), the perimeter is given by 4x units. So, as the length of the side varies, the perimeter varies.

Can you find the area of the square PQRS? It is x × x = x2 square units. x2 is an algebraic expression. You are also familiar with other algebraic expressions like

Can you find the area of the square PQRS? It is x × x = x2 square units. x2 is an algebraic expression. You are also familiar with other algebraic expressions like

2x, x2 + 2x, x3 – x2 + 4x + 7. Note that, all the algebraic expressions we have considered so far have only whole numbers as the exponents of the variable. Expressions of this form are called polynomials in one variable. In the examples above, the variable is x. For instance, x3 – x2 + 4x + 7 is a polynomial in x. Similarly, 3y2 + 5y is a polynomial in the variable y and t2 + 4 is a polynomial in the variable t.

In the polynomial x2 + 2x, the expressions x2 and 2x are called the terms of the polynomial. Similarly, the polynomial 3y2 + 5y + 7 has three terms, namely, 3y2, 5y and 7. Can you write the terms of the polynomial –x3 + 4x2 + 7x – 2 ? This polynomial has 4 terms, namely, –x3, 4x2, 7x and –2.

Each term of a polynomial has a coefficient. So, in –x3 + 4x2 + 7x – 2, the coefficient of x3 is –1, the coefficient of x2 is 4, the coefficient of x is 7 and –2 is the coefficient of x0 (Remember, x0 = 1). Do you know the coefficient of x in x2 – x + 7? It is –1.

2 is also a polynomial. In fact, 2, –5, 7, etc. are examples of constant polynomials. The constant polynomial 0 is called the zero polynomial. This plays a very important role in the collection of all polynomials, as you will see in the higher classes.

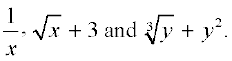

Now, consider algebraic expressions such as x +  Do you know that you can write x +

Do you know that you can write x +  = x + x–1? Here, the exponent of the second term, i.e., x–1 is –1, which is not a whole number. So, this algebraic expression is not a polynomial.

= x + x–1? Here, the exponent of the second term, i.e., x–1 is –1, which is not a whole number. So, this algebraic expression is not a polynomial.

Again,  can be written as

can be written as  . Here the exponent of x is

. Here the exponent of x is  , which is not a whole number. So, is

, which is not a whole number. So, is  a polynomial? No, it is not. What about

a polynomial? No, it is not. What about + y2? It is also not a polynomial (Why?).

+ y2? It is also not a polynomial (Why?).

If the variable in a polynomial is x, we may denote the polynomial by p(x), or q(x), or r(x), etc. So, for example, we may write :

p(x) = 2x2 + 5x – 3

q(x) = x3 –1

r(y) = y3 + y + 1

s(u) = 2 – u – u2 + 6u5

A polynomial can have any (finite) number of terms. For instance, x150 + x149 + ...

+ x2 + x + 1 is a polynomial with 151 terms.

Consider the polynomials 2x, 2, 5x3, –5x2, y and u4. Do you see that each of these polynomials has only one term? Polynomials having only one term are called monomials (‘mono’ means ‘one’).

Now observe each of the following polynomials:

p(x) = x + 1, q(x) = x2 – x, r(y) = y9 + 1, t(u) = u15 – u2

How many terms are there in each of these? Each of these polynomials has only two terms. Polynomials having only two terms are called binomials (‘bi’ means ‘two’).

Similarly, polynomials having only three terms are called trinomials (‘tri’ means ‘three’). Some examples of trinomials are

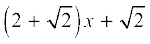

p(x) = x + x2 + π, q(x) = + x – x2,

+ x – x2,

r(u) = u + u2 – 2, t(y) = y4 + y + 5.

Now, look at the polynomial p(x) = 3x7 – 4x6 + x + 9. What is the term with the highest power of x ? It is 3x7. The exponent of x in this term is 7. Similarly, in the polynomial q(y) = 5y6 – 4y2 – 6, the term with the highest power of y is 5y6 and the exponent of y in this term is 6. We call the highest power of the variable in a polynomial as the degree of the polynomial. So, the degree of the polynomial 3x7 – 4x6 + x + 9 is 7 and the degree of the polynomial 5y6 – 4y2 – 6 is 6. The degree of a non-zero constant polynomial is zero.

Example 1 : Find the degree of each of the polynomials given below:

(i) x5 – x4 + 3 (ii) 2 – y2 – y3 + 2y8 (iii) 2

Solution : (i) The highest power of the variable is 5. So, the degree of the polynomial is 5.

(ii) The highest power of the variable is 8. So, the degree of the polynomial is 8.

(iii) The only term here is 2 which can be written as 2x0. So the exponent of x is 0. Therefore, the degree of the polynomial is 0.

Now observe the polynomials p(x) = 4x + 5, q(y) = 2y, r(t) = t +  and s(u) = 3 – u. Do you see anything common among all of them? The degree of each of these polynomials is one. A polynomial of degree one is called a linear polynomial. Some more linear polynomials in one variable are 2x – 1,

and s(u) = 3 – u. Do you see anything common among all of them? The degree of each of these polynomials is one. A polynomial of degree one is called a linear polynomial. Some more linear polynomials in one variable are 2x – 1,  y + 1, 2 – u. Now, try and find a linear polynomial in x with 3 terms? You would not be able to find it because a linear polynomial in x can have at most two terms. So, any linear polynomial in x will be of the form ax + b, where a and b are constants and a ≠ 0 (why?). Similarly,

y + 1, 2 – u. Now, try and find a linear polynomial in x with 3 terms? You would not be able to find it because a linear polynomial in x can have at most two terms. So, any linear polynomial in x will be of the form ax + b, where a and b are constants and a ≠ 0 (why?). Similarly,

ay + b is a linear polynomial in y.

Now consider the polynomials :

2x2 + 5, 5x2 + 3x + π, x2 and x2 +  x

x

Do you agree that they are all of degree two? A polynomial of degree two is called a quadratic polynomial. Some examples of a quadratic polynomial are 5 – y2, 4y + 5y2 and 6 – y – y2. Can you write a quadratic polynomial in one variable with four different terms? You will find that a quadratic polynomial in one variable will have at most 3 terms. If you list a few more quadratic polynomials, you will find that any quadratic polynomial in x is of the form ax2 + bx + c, where a ≠ 0 and a, b, c are constants. Similarly, quadratic polynomial in y will be of the form ay2 + by + c, provided a ≠ 0 and a, b, c are constants.

We call a polynomial of degree three a cubic polynomial. Some examples of a cubic polynomial in x are 4x3, 2x3 + 1, 5x3 + x2, 6x3 – x, 6 – x3, 2x3 + 4x2 + 6x + 7. How many terms do you think a cubic polynomial in one variable can have? It can have at most 4 terms. These may be written in the form ax3 + bx2 + cx + d, where a ≠ 0 and a, b, c and d are constants.

Now, that you have seen what a polynomial of degree 1, degree 2, or degree 3 looks like, can you write down a polynomial in one variable of degree n for any natural number n? A polynomial in one variable x of degree n is an expression of the form

anxn + an–1xn–1 + . . . + a1x + a0

where a0, a1, a2, . . ., an are constants and an ≠ 0.

In particular, if a0 = a1 = a2 = a3 = . . . = an = 0 (all the constants are zero), we get the zero polynomial, which is denoted by 0. What is the degree of the zero polynomial? The degree of the zero polynomial is not defined.

So far we have dealt with polynomials in one variable only. We can also have polynomials in more than one variable. For example, x2 + y2 + xyz (where variables are x, y and z) is a polynomial in three variables. Similarly p2 + q10 + r (where the variables are p, q and r), u3 + v2 (where the variables are u and v) are polynomials in three and two variables, respectively. You will be studying such polynomials in detail later.

Exercise 2.1

1. Which of the following expressions are polynomials in one variable and which are not? State reasons for your answer.

(i) 4x2 – 3x + 7 (ii) y2 +  (iii)

(iii)  (iv) y +

(iv) y +

(v) x10 + y3 + t50

2. Write the coefficients of x2 in each of the following:

(i) 2 + x2 + x (ii) 2 – x2 + x3 (iii)  (iv)

(iv)

3. Give one example each of a binomial of degree 35, and of a monomial of degree 100.

4. Write the degree of each of the following polynomials:

(i) 5x3 + 4x2 + 7x (ii) 4 – y2

(iii) 5t –  (iv) 3

(iv) 3

5. Classify the following as linear, quadratic and cubic polynomials:

(i) x2 + x (ii) x – x3 (iii) y + y2 + 4 (iv) 1 + x

(v) 3t (vi) r2 (vii) 7x3

2.3 Zeroes of a Polynomial

Consider the polynomial p(x) = 5x3 – 2x2 + 3x – 2.

If we replace x by 1 everywhere in p(x), we get

p(1) = 5 × (1)3 – 2 × (1)2 + 3 × (1) – 2

= 5 – 2 + 3 –2

= 4

So, we say that the value of p(x) at x = 1 is 4.

Similarly, p(0) = 5(0)3 – 2(0)2 + 3(0) –2

= –2

Can you find p(–1)?

Example 2 : Find the value of each of the following polynomials at the indicated value of variables:

(i) p(x) = 5x2 – 3x + 7 at x = 1.

(ii) q(y) = 3y3 – 4y +  at y = 2.

at y = 2.

(iii) p(t) = 4t4 + 5t3 – t2 + 6 at t = a.

Solution : (i) p(x) = 5x2 – 3x + 7

The value of the polynomial p(x) at x = 1 is given by

p(1) = 5(1)2 – 3(1) + 7

= 5 – 3 + 7 = 9

(ii) q(y) = 3y3 – 4y +

The value of the polynomial q(y) at y = 2 is given by

q(2) = 3(2)3 – 4(2) +  = 24 – 8 +

= 24 – 8 +  = 16 +

= 16 +

(iii) p(t) = 4t4 + 5t3 – t2 + 6

The value of the polynomial p(t) at t = a is given by

p(a) = 4a4 + 5a3 – a2 + 6

Now, consider the polynomial p(x) = x – 1.

What is p(1)? Note that : p(1) = 1 – 1 = 0.

As p(1) = 0, we say that 1 is a zero of the polynomial p(x).

Similarly, you can check that 2 is a zero of q(x), where q(x) = x – 2.

In general, we say that a zero of a polynomial p(x) is a number c such that p(c) = 0.

You must have observed that the zero of the polynomial x – 1 is obtained by equating it to 0, i.e., x – 1 = 0, which gives x = 1. We say p(x) = 0 is a polynomial equation and 1 is the root of the polynomial equation p(x) = 0. So we say 1 is the zero of the polynomial x – 1, or a root of the polynomial equation x – 1 = 0.

Now, consider the constant polynomial 5. Can you tell what its zero is? It has no zero because replacing x by any number in 5x0 still gives us 5. In fact, a non-zero constant polynomial has no zero. What about the zeroes of the zero polynomial? By convention, every real number is a zero of the zero polynomial.

Example 3 : Check whether –2 and 2 are zeroes of the polynomial x + 2.

Solution : Let p(x) = x + 2.

Then p(2) = 2 + 2 = 4, p(–2) = –2 + 2 = 0

Therefore, –2 is a zero of the polynomial x + 2, but 2 is not.

Example 4 : Find a zero of the polynomial p(x) = 2x + 1.

Solution : Finding a zero of p(x), is the same as solving the equation

p(x) = 0

Now, 2x + 1 = 0 gives us x =

So,  is a zero of the polynomial 2x + 1.

is a zero of the polynomial 2x + 1.

Now, if p(x) = ax + b, a ≠ 0, is a linear polynomial, how can we find a zero of p(x)? Example 4 may have given you some idea. Finding a zero of the polynomial p(x), amounts to solving the polynomial equation p(x) = 0.

Now, p(x) = 0 means ax + b = 0, a ≠ 0

So, ax = –b

i.e., x =  .

.

So, x =  is the only zero of p(x), i.e., a linear polynomial has one and only one zero.

is the only zero of p(x), i.e., a linear polynomial has one and only one zero.

Now we can say that 1 is the zero of x – 1, and –2 is the zero of x + 2.

Example 5 : Verify whether 2 and 0 are zeroes of the polynomial x2 – 2x.

Solution : Let p(x) = x2 – 2x

Then p(2) = 22 – 4 = 4 – 4 = 0

and p(0) = 0 – 0 = 0

Hence, 2 and 0 are both zeroes of the polynomial x2 – 2x.

Let us now list our observations:

(i) A zero of a polynomial need not be 0.

(ii) 0 may be a zero of a polynomial.

(iii) Every linear polynomial has one and only one zero.

(iv) A polynomial can have more than one zero.

Exercise 2.2

1. Find the value of the polynomial 5x – 4x2 + 3 at

(i) x = 0 (ii) x = –1 (iii) x = 2

2. Find p(0), p(1) and p(2) for each of the following polynomials:

(i) p(y) = y2 – y + 1 (ii) p(t) = 2 + t + 2t2 – t3

(iii) p(x) = x3 (iv) p(x) = (x – 1) (x + 1)

3. Verify whether the following are zeroes of the polynomial, indicated against them.

(i) p(x) = 3x + 1, x =  (ii) p(x) = 5x – π, x =

(ii) p(x) = 5x – π, x =

(iii) p(x) = x2 – 1, x = 1, –1 (iv) p(x) = (x + 1) (x – 2), x = – 1, 2

(v) p(x) = x2, x = 0 (vi) p(x) = lx + m, x =

(vii) p(x) = 3x2 – 1, x =  (viii) p(x) = 2x + 1, x =

(viii) p(x) = 2x + 1, x =

4. Find the zero of the polynomial in each of the following cases:

(i) p(x) = x + 5 (ii) p(x) = x – 5 (iii) p(x) = 2x + 5

(iv) p(x) = 3x – 2 (v) p(x) = 3x (vi) p(x) = ax, a ≠ 0

(vii) p(x) = cx + d, c ≠ 0, c, d are real numbers.

2.4 Remainder Theorem

Let us consider two numbers 15 and 6. You know that when we divide 15 by 6, we get the quotient 2 and remainder 3. Do you remember how this fact is expressed? We write 15 as

15 = (6 × 2) + 3

We observe that the remainder 3 is less than the divisor 6. Similarly, if we divide 12 by 6, we get

12 = (6 × 2) + 0

What is the remainder here? Here the remainder is 0, and we say that 6 is a factor of 12 or 12 is a multiple of 6.

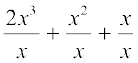

Now, the question is: can we divide one polynomial by another? To start with, let us try and do this when the divisor is a monomial. So, let us divide the polynomial

2x3 + x2 + x by the monomial x.

We have (2x3 + x2 + x) ÷ x =

= 2x2 + x + 1

In fact, you may have noticed that x is common to each term of 2x3 + x2 + x. So we can write 2x3 + x2 + x as x(2x2 + x + 1).

We say that x and 2x2 + x + 1 are factors of 2x3 + x2 + x, and 2x3 + x2 + x is a multiple of x as well as a multiple of 2x2 + x + 1.

Consider another pair of polynomials 3x2 + x + 1 and x.

Here, (3x2 + x + 1) ÷ x = (3x2 ÷ x) + (x ÷ x) + (1 ÷ x).

We see that we cannot divide 1 by x to get a polynomial term. So in this case we stop here, and note that 1 is the remainder. Therefore, we have

3x2 + x + 1 = {x × (3x + 1)} + 1

In this case, 3x + 1 is the quotient and 1 is the remainder. Do you think that x is a factor of 3x2 + x + 1? Since the remainder is not zero, it is not a factor.

Now let us consider an example to see how we can divide a polynomial by any non-zero polynomial.

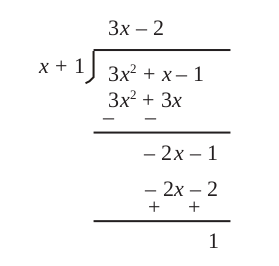

Example 6 : Divide p(x) by g(x), where p(x) = x + 3x2 – 1 and g(x) = 1 + x.

Solution : We carry out the process of division by means of the following steps:

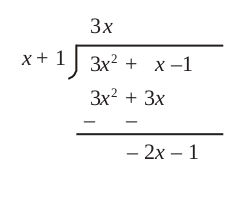

Step 1 : We write the dividend x + 3x2 – 1 and the divisor 1 + x in the standard form, i.e., after arranging the terms in the descending order of their degrees. So, the dividend is 3x2 + x –1 and divisor is x + 1.

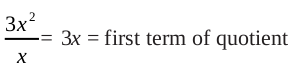

Step 2 : We divide the first term of the dividend by the first term of the divisor, i.e., we divide 3x2 by x, and get 3x. This gives us the first term of the quotient.

Step 3 : We multiply the divisor by the first term of the quotient, and subtract this product from the dividend, i.e., we multiply x + 1 by 3x and subtract the product 3x2 + 3x from the dividend 3x2 + x – 1. This gives us the remainder as –2x – 1.

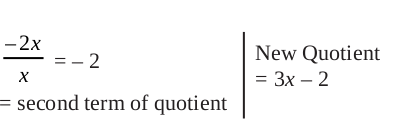

Step 4 : We treat the remainder –2x – 1 as the new dividend. The divisor remains the same. We repeat Step 2 to get the next term of the quotient, i.e., we divide the first term – 2x of the (new) dividend by the first term x of the divisor and obtain – 2. Thus, – 2 is the second term in the quotient.

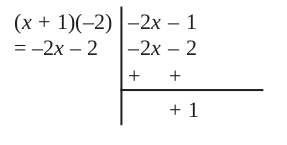

Step 5 : We multiply the divisor by the second term of the quotient and subtract the product from the dividend. That is, we multiply x + 1 by – 2 and subtract the product – 2x – 2 from the dividend – 2x – 1. This gives us 1 as the remainder.

This process continues till the remainder is 0 or the degree of the new dividend is less than the degree of the divisor. At this stage, this new dividend becomes the remainder and the sum of the quotients gives us the whole quotient.

Step 6 : Thus, the quotient in full is 3x – 2 and the remainder is 1.

Let us look at what we have done in the process above as a whole:

Notice that 3x2 + x – 1 = (x + 1) (3x – 2) + 1

i.e., Dividend = (Divisor × Quotient) + Remainder

In general, if p(x) and g(x) are two polynomials such that degree of p(x) ≥ degree of g(x) and g(x) ≠ 0, then we can find polynomials q(x) and r(x) such that:

p(x) = g(x)q(x) + r(x),

where r(x) = 0 or degree of r(x) < degree of g(x). Here we say that p(x) divided by g(x), gives q(x) as quotient and r(x) as remainder.

In the example above, the divisor was a linear polynomial. In such a situation, let us see if there is any link between the remainder and certain values of the dividend.

In p(x) = 3x2 + x – 1, if we replace x by –1, we have

p(–1) = 3(–1)2 + (–1) –1 = 1

So, the remainder obtained on dividing p(x) = 3x2 + x – 1 by x + 1 is the same as the value of the polynomial p(x) at the zero of the polynomial x + 1, i.e., –1.

Let us consider some more examples.

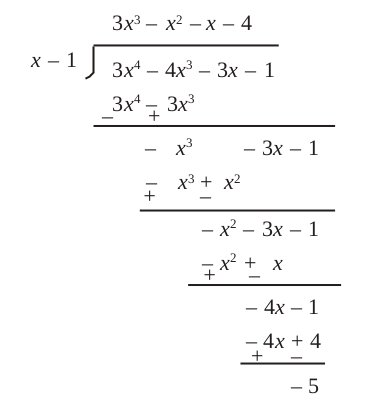

Example 7 : Divide the polynomial 3x4 – 4x3 – 3x –1 by x – 1.

Solution : By long division, we have:

Here, the remainder is – 5. Now, the zero of x – 1 is 1. So, putting x = 1 in p(x), we see that

p(1) = 3(1)4 – 4(1)3 – 3(1) – 1

= 3 – 4 – 3 – 1

= – 5, which is the remainder.

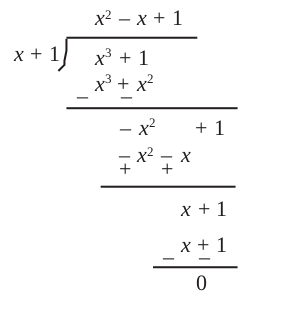

Example 8 : Find the remainder obtained on dividing p(x) = x3 + 1 by x + 1.

Solution : By long division,

So, we find that the remainder is 0.

Here p(x) = x3 + 1, and the root of x + 1 = 0 is x = –1. We see that

p(–1) = (–1)3 + 1

= –1 + 1

= 0,

which is equal to the remainder obtained by actual division.

Is it not a simple way to find the remainder obtained on dividing a polynomial by a linear polynomial? We shall now generalise this fact in the form of the following theorem. We shall also show you why the theorem is true, by giving you a proof of the theorem.

Remainder Theorem : Let p(x) be any polynomial of degree greater than or equal to one and let a be any real number. If p(x) is divided by the linear polynomial x – a, then the remainder is p(a).

Proof : Let p(x) be any polynomial with degree greater than or equal to 1. Suppose that when p(x) is divided by x – a, the quotient is q(x) and the remainder is r(x), i.e.,

p(x) = (x – a) q(x) + r(x)

Since the degree of x – a is 1 and the degree of r(x) is less than the degree of x – a, the degree of r(x) = 0. This means that r(x) is a constant, say r.

So, for every value of x, r(x) = r.

Therefore, p(x) = (x – a) q(x) + r

In particular, if x = a, this equation gives us

p(a) = (a – a) q(a) + r

= r,

which proves the theorem.

Let us use this result in another example.

Example 9 : Find the remainder when x4 + x3 – 2x2 + x + 1 is divided by x – 1.

Solution : Here, p(x) = x4 + x3 – 2x2 + x + 1, and the zero of x – 1 is 1.

So, p(1) = (1)4 + (1)3 – 2(1)2 + 1 + 1

= 2

So, by the Remainder Theorem, 2 is the remainder when x4 + x3 – 2x2 + x + 1 is divided by x – 1.

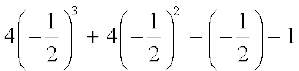

Example 10 : Check whether the polynomial q(t) = 4t3 + 4t2 – t – 1 is a multiple of

2t + 1.

Solution : As you know, q(t) will be a multiple of 2t + 1 only, if 2t + 1 divides q(t) leaving remainder zero. Now, taking 2t + 1 = 0, we have t =  .

.

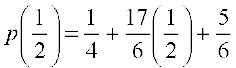

Also, q  =

=  =

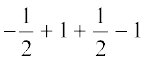

=  = 0

= 0

So the remainder obtained on dividing q(t) by 2t + 1 is 0.

So, 2t + 1 is a factor of the given polynomial q(t), that is q(t) is a multiple of

2t + 1.

Exercise 2.3

1. Find the remainder when x3 + 3x2 + 3x + 1 is divided by

(i) x + 1 (ii) x –  (iii) x (iv) x + π (v) 5 + 2x

(iii) x (iv) x + π (v) 5 + 2x

2. Find the remainder when x3 – ax2 + 6x – a is divided by x – a.

3. Check whether 7 + 3x is a factor of 3x3 + 7x.

2.5 Factorisation of Polynomials

Let us now look at the situation of Example 10 above more closely. It tells us that since the remainder,  = 0, (2t + 1) is a factor of q(t), i.e., q(t) = (2t + 1) g(t)

= 0, (2t + 1) is a factor of q(t), i.e., q(t) = (2t + 1) g(t)

for some polynomial g(t). This is a particular case of the following theorem.

Factor Theorem : If p(x) is a polynomial of degree n > 1 and a is any real number, then (i) x – a is a factor of p(x), if p(a) = 0, and (ii) p(a) = 0, if x – a is a factor of p(x).

Proof: By the Remainder Theorem, p(x)=(x – a) q(x) + p(a).

(i) If p(a) = 0, then p(x) = (x – a) q(x), which shows that x – a is a factor of p(x).

(ii) Since x – a is a factor of p(x), p(x) = (x – a) g(x) for same polynomial g(x). In this case, p(a) = (a – a) g(a) = 0.

Example 11 : Examine whether x + 2 is a factor of x3 + 3x2 + 5x + 6 and of 2x + 4.

Solution : The zero of x + 2 is –2. Let p(x) = x3 + 3x2 + 5x + 6 and s(x) = 2x + 4

Then, p(–2) = (–2)3 + 3(–2)2 + 5(–2) + 6

= –8 + 12 – 10 + 6

= 0

So, by the Factor Theorem, x + 2 is a factor of x3 + 3x2 + 5x + 6.

Again, s(–2) = 2(–2) + 4 = 0

So, x + 2 is a factor of 2x + 4. In fact, you can check this without applying the Factor Theorem, since 2x + 4 = 2(x + 2).

Example 12 : Find the value of k, if x – 1 is a factor of 4x3 + 3x2 – 4x + k.

Solution : As x – 1 is a factor of p(x) = 4x3 + 3x2 – 4x + k, p(1) = 0

Now, p(1) = 4(1)3 + 3(1)2 – 4(1) + k

So, 4 + 3 – 4 + k = 0

i.e., k = –3

We will now use the Factor Theorem to factorise some polynomials of degree 2 and 3. You are already familiar with the factorisation of a quadratic polynomial like

x2 + lx + m. You had factorised it by splitting the middle term lx as ax + bx so that

ab = m. Then x2 + lx + m = (x + a) (x + b). We shall now try to factorise quadratic polynomials of the type ax2 + bx + c, where a ≠ 0 and a, b, c are constants.

Factorisation of the polynomial ax2 + bx + c by splitting the middle term is as follows:

Let its factors be (px + q) and (rx + s). Then

ax2 + bx + c = (px + q) (rx + s) = pr x2 + (ps + qr) x + qs

Comparing the coefficients of x2, we get a = pr.

Similarly, comparing the coefficients of x, we get b = ps + qr.

And, on comparing the constant terms, we get c = qs.

This shows us that b is the sum of two numbers ps and qr, whose product is

(ps)(qr) = (pr)(qs) = ac.

Therefore, to factorise ax2 + bx + c, we have to write b as the sum of two numbers whose product is ac. This will be clear from Example 13.

Example 13 : Factorise 6x2 + 17x + 5 by splitting the middle term, and by using the Factor Theorem.

Solution 1 : (By splitting method) : If we can find two numbers p and q such that

p + q = 17 and pq = 6 × 5 = 30, then we can get the factors.

So, let us look for the pairs of factors of 30. Some are 1 and 30, 2 and 15, 3 and 10, 5 and 6. Of these pairs, 2 and 15 will give us p + q = 17.

So, 6x2 + 17x + 5 = 6x2 + (2 + 15)x + 5

= 6x2 + 2x + 15x + 5

= 2x(3x + 1) + 5(3x + 1)

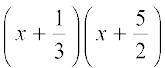

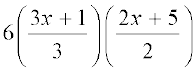

= (3x + 1) (2x + 5)

Solution 2 : (Using the Factor Theorem)

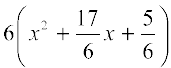

6x2 + 17x + 5 =  = 6 p(x), say. If a and b are the zeroes of p(x), then 6x2 + 17x + 5 = 6(x – a) (x – b). So, ab =

= 6 p(x), say. If a and b are the zeroes of p(x), then 6x2 + 17x + 5 = 6(x – a) (x – b). So, ab =  Let us look at some possibilities for a and b. They could be

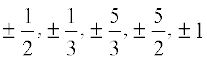

Let us look at some possibilities for a and b. They could be  . Now,

. Now,  ≠ 0. But

≠ 0. But

= 0. So,

= 0. So,  is a factor of p(x). Similarly, by trial, you can find that

is a factor of p(x). Similarly, by trial, you can find that  is a factor of p(x).

is a factor of p(x).

Therefore, 6x2 + 17x + 5 = 6

=

= (3x + 1) (2x + 5)

For the example above, the use of the splitting method appears more efficient. However, let us consider another example.

Example 14 : Factorise y2 – 5y + 6 by using the Factor Theorem.

Solution : Let p(y) = y2 – 5y + 6. Now, if p(y) = (y – a) (y – b), you know that the constant term will be ab. So, ab = 6. So, to look for the factors of p(y), we look at the factors of 6.

The factors of 6 are 1, 2 and 3.

Now, p(2) = 22 – (5 × 2) + 6 = 0

So, y – 2 is a factor of p(y).

Also, p(3) = 32 – (5 × 3) + 6 = 0

So, y – 3 is also a factor of y2 – 5y + 6.

Therefore, y2 – 5y + 6 = (y – 2)(y – 3)

Note that y2 – 5y + 6 can also be factorised by splitting the middle term –5y.

Now, let us consider factorising cubic polynomials. Here, the splitting method will not be appropriate to start with. We need to find at least one factor first, as you will see in the following example.

Example 15 : Factorise x3 – 23x2 + 142x – 120.

Solution : Let p(x) = x3 – 23x2 + 142x – 120

We shall now look for all the factors of –120. Some of these are ±1, ±2, ±3,

±4, ±5, ±6, ±8, ±10, ±12, ±15, ±20, ±24, ±30, ±60.

By trial, we find that p(1) = 0. So x – 1 is a factor of p(x).

Now we see that x3 – 23x2 + 142x – 120 = x3 – x2 – 22x2 + 22x + 120x – 120

= x2(x –1) – 22x(x – 1) + 120(x – 1) (Why?)

= (x – 1) (x2 – 22x + 120) [Taking (x – 1) common]

We could have also got this by dividing p(x) by x – 1.

Now x2 – 22x + 120 can be factorised either by splitting the middle term or by using the Factor theorem. By splitting the middle term, we have:

x2 – 22x + 120 = x2 – 12x – 10x + 120

= x(x – 12) – 10(x – 12)

= (x – 12) (x – 10)

So, x3 – 23x2 – 142x – 120 = (x – 1)(x – 10)(x – 12)

Exercise 2.4

1. Determine which of the following polynomials has (x + 1) a factor :

(i) x3 + x2 + x + 1 (ii) x4 + x3 + x2 + x + 1

(iii) x4 + 3x3 + 3x2 + x + 1 (iv) x3 – x2 –

2. Use the Factor Theorem to determine whether g(x) is a factor of p(x) in each of the following cases:

(i) p(x) = 2x3 + x2 – 2x – 1, g(x) = x + 1

(ii) p(x) = x3 + 3x2 + 3x + 1, g(x) = x + 2

(iii) p(x) = x3 – 4x2 + x + 6, g(x) = x – 3

3. Find the value of k, if x – 1 is a factor of p(x) in each of the following cases:

(i) p(x) = x2 + x + k (ii) p(x) = 2x2 + kx +

(iii) p(x) = kx2 –  x + 1 (iv) p(x) = kx2 – 3x + k

x + 1 (iv) p(x) = kx2 – 3x + k

4. Factorise :

(i) 12x2 – 7x + 1 (ii) 2x2 + 7x + 3

(iii) 6x2 + 5x – 6 (iv) 3x2 – x – 4

5. Factorise :

(i) x3 – 2x2 – x + 2 (ii) x3 – 3x2 – 9x – 5

(iii) x3 + 13x2 + 32x + 20 (iv) 2y3 + y2 – 2y – 1

2.6 Algebraic Identities

From your earlier classes, you may recall that an algebraic identity is an algebraic equation that is true for all values of the variables occurring in it. You have studied the following algebraic identities in earlier classes:

Identity I : (x + y)2 = x2 + 2xy + y2

Identity II : (x – y)2 = x2 – 2xy + y2

Identity III : x2 – y2 = (x + y) (x – y)

Identity IV : (x + a) (x + b) = x2 + (a + b)x + ab

You must have also used some of these algebraic identities to factorise the algebraic expressions. You can also see their utility in computations.

Example 16 : Find the following products using appropriate identities:

(i) (x + 3) (x + 3) (ii) (x – 3) (x + 5)

Solution : (i) Here we can use Identity I : (x + y)2 = x2 + 2xy + y2. Putting y = 3 in it, we get

(x + 3) (x + 3) = (x + 3)2 = x2 + 2(x)(3) + (3)2

= x2 + 6x + 9

(ii) Using Identity IV above, i.e., (x + a) (x + b) = x2 + (a + b)x + ab, we have

(x – 3) (x + 5) = x2 + (–3 + 5)x + (–3)(5)

= x2 + 2x – 15

Example 17 : Evaluate 105 × 106 without multiplying directly.

Solution : 105 × 106 = (100 + 5) × (100 + 6)

= (100)2 + (5 + 6) (100) + (5 × 6), using Identity IV

= 10000 + 1100 + 30

= 11130

You have seen some uses of the identities listed above in finding the product of some given expressions. These identities are useful in factorisation of algebraic expressions also, as you can see in the following examples.

Example 18 : Factorise:

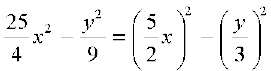

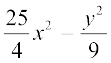

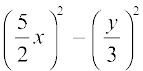

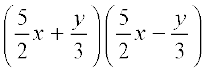

(i) 49a2 + 70ab + 25b2 (ii)

Solution : (i) Here you can see that

49a2 = (7a)2, 25b2 = (5b)2, 70ab = 2(7a) (5b)

Comparing the given expression with x2 + 2xy + y2, we observe that x = 7a and y = 5b.

Using Identity I, we get

49a2 + 70ab + 25b2 = (7a + 5b)2 = (7a + 5b) (7a + 5b)

(ii) We have

Now comparing it with Identity III, we get

=

=

=

So far, all our identities involved products of binomials. Let us now extend the Identity I to a trinomial x + y + z. We shall compute (x + y + z)2 by using Identity I.

Let x + y = t. Then,

(x + y + z)2 = (t + z)2

= t2 + 2tz + t2 (Using Identity I)

= (x + y)2 + 2(x + y)z + z2 (Substituting the value of t)

= x2 + 2xy + y2 + 2xz + 2yz + z2 (Using Identity I)

= x2 + y2 + z2 + 2xy + 2yz + 2zx (Rearranging the terms)

So, we get the following identity:

Identity V : (x + y + z)2 = x2 + y2 + z2 + 2xy + 2yz + 2zx

Remark : We call the right hand side expression the expanded form of the left hand side expression. Note that the expansion of (x + y + z)2 consists of three square terms and three product terms.

Example 19 : Write (3a + 4b + 5c)2 in expanded form.

Solution : Comparing the given expression with (x + y + z)2, we find that

x = 3a, y = 4b and z = 5c.

Therefore, using Identity V, we have

(3a + 4b + 5c)2 = (3a)2 + (4b)2 + (5c)2 + 2(3a)(4b) + 2(4b)(5c) + 2(5c)(3a)

= 9a2 + 16b2 + 25c2 + 24ab + 40bc + 30ac

Example 20 : Expand (4a – 2b – 3c)2.

Solution : Using Identity V, we have

(4a – 2b – 3c)2 = [4a + (–2b) + (–3c)]2

= (4a)2 + (–2b)2 + (–3c)2 + 2(4a)(–2b) + 2(–2b)(–3c) + 2(–3c)(4a)

= 16a2 + 4b2 + 9c2 – 16ab + 12bc – 24ac

Example 21 : Factorise 4x2 + y2 + z2 – 4xy – 2yz + 4xz.

Solution : We have 4x2 + y2 + z2 – 4xy – 2yz + 4xz = (2x)2 + (–y)2 + (z)2 + 2(2x)(–y)

+ 2(–y)(z) + 2(2x)(z)

= [2x + (–y) + z]2 (Using Identity V)

= (2x – y + z)2 = (2x – y + z)(2x – y + z)

So far, we have dealt with identities involving second degree terms. Now let us extend Identity I to compute (x + y)3. We have:

(x + y)3 = (x + y) (x + y)2

= (x + y)(x2 + 2xy + y2)

= x(x2 + 2xy + y2) + y(x2 + 2xy + y2)

= x3 + 2x2y + xy2 + x2y + 2xy2 + y3

= x3 + 3x2y + 3xy2 + y3

= x3 + y3 + 3xy(x + y)

So, we get the following identity:

Identity VI : (x + y)3 = x3 + y3 + 3xy (x + y)

Also, by replacing y by –y in the Identity VI, we get

Identity VII : (x – y)3 = x3 – y3 – 3xy(x – y)

= x3 – 3x2y + 3xy2 – y3

Example 22 : Write the following cubes in the expanded form:

(i) (3a + 4b)3 (ii) (5p – 3q)3

Solution : (i) Comparing the given expression with (x + y)3, we find that

x = 3a and y = 4b.

So, using Identity VI, we have:

(3a + 4b)3 = (3a)3 + (4b)3 + 3(3a)(4b)(3a + 4b)

= 27a3 + 64b3 + 108a2b + 144ab2

(ii) Comparing the given expression with (x – y)3, we find that

x = 5p, y = 3q.

So, using Identity VII, we have:

(5p – 3q)3 = (5p)3 – (3q)3 – 3(5p)(3q)(5p – 3q)

= 125p3 – 27q3 – 225p2q + 135pq2

Example 23 : Evaluate each of the following using suitable identities:

(i) (104)3 (ii) (999)3

Solution : (i) We have

(104)3 = (100 + 4)3

= (100)3 + (4)3 + 3(100)(4)(100 + 4)

(Using Identity VI)

= 1000000 + 64 + 124800

= 1124864

(ii) We have

(999)3 = (1000 – 1)3

= (1000)3 – (1)3 – 3(1000)(1)(1000 – 1)

(Using Identity VII)

= 1000000000 – 1 – 2997000

= 997002999

Example 24 : Factorise 8x3 + 27y3 + 36x2y + 54xy2

Solution : The given expression can be written as

(2x)3 + (3y)3 + 3(4x2)(3y) + 3(2x)(9y2)

= (2x)3 + (3y)3 + 3(2x)2(3y) + 3(2x)(3y)2

= (2x + 3y)3 (Using Identity VI)

= (2x + 3y)(2x + 3y)(2x + 3y)

Now consider (x + y + z)(x2 + y2 + z2 – xy – yz – zx)

On expanding, we get the product as

x(x2 + y2 + z2 – xy – yz – zx) + y(x2 + y2 + z2 – xy – yz – zx)

+ z(x2 + y2 + z2 – xy – yz – zx) = x3 + xy2 + xz2 – x2y – xyz – zx2 + x2y

+ y3 + yz2 – xy2 – y2z – xyz + x2z + y2z + z3 – xyz – yz2 – xz2

= x3 + y3 + z3 – 3xyz (On simplification)

So, we obtain the following identity:

Identity VIII : x3 + y3 + z3 – 3xyz = (x + y + z)(x2 + y2 + z2 – xy – yz – zx)

Example 25 : Factorise : 8x3 + y3 + 27z3 – 18xyz

Solution : Here, we have

8x3 + y3 + 27z3 – 18xyz

= (2x)3 + y3 + (3z)3 – 3(2x)(y)(3z)

= (2x + y + 3z)[(2x)2 + y2 + (3z)2 – (2x)(y) – (y)(3z) – (2x)(3z)]

= (2x + y + 3z) (4x2 + y2 + 9z2 – 2xy – 3yz – 6xz)

Exercise 2.5

1. Use suitable identities to find the following products:

(i) (x + 4) (x + 10) (ii) (x + 8) (x – 10) (iii) (3x + 4) (3x – 5)

(iv) (y2 +  ) (y2 –

) (y2 –  ) (v) (3 – 2x) (3 + 2x)

) (v) (3 – 2x) (3 + 2x)

2. Evaluate the following products without multiplying directly:

(i) 103 × 107 (ii) 95 × 96 (iii) 104 × 96

3. Factorise the following using appropriate identities:

(i) 9x2 + 6xy + y2 (ii) 4y2 – 4y + 1 (iii) x2 –

4. Expand each of the following, using suitable identities:

(i) (x + 2y + 4z)2 (ii) (2x – y + z)2 (iii) (–2x + 3y + 2z)2

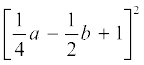

(iv) (3a – 7b – c)2 (v) (–2x + 5y – 3z)2 (vi)

5. Factorise:

(i) 4x2 + 9y2 + 16z2 + 12xy – 24yz – 16xz

(ii) 2x2 + y2 + 8z2 –  xy +

xy +  yz – 8xz

yz – 8xz

6. Write the following cubes in expanded form:

(i) (2x + 1)3 (ii) (2a – 3b)3 (iii)  (iv)

(iv)

7. Evaluate the following using suitable identities:

(i) (99)3 (ii) (102)3 (iii) (998)3

8. Factorise each of the following:

(i) 8a3 + b3 + 12a2b + 6ab2 (ii) 8a3 – b3 – 12a2b + 6ab2

(iii) 27 – 125a3 – 135a + 225a2 (iv) 64a3 – 27b3 – 144a2b + 108ab2

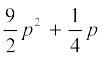

(v) 27p3 –  –

–

9. Verify : (i) x3 + y3 = (x + y) (x2 – xy + y2) (ii) x3 – y3 = (x – y) (x2 + xy + y2)

10. Factorise each of the following:

(i) 27y3 + 125z3 (ii) 64m3 – 343n3

[Hint : See Question 9.]

11. Factorise : 27x3 + y3 + z3 – 9xyz

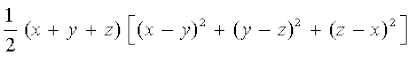

12. Verify that x3 + y3 + z3 – 3xyz =

13. If x + y + z = 0, show that x3 + y3 + z3 = 3xyz.

14. Without actually calculating the cubes, find the value of each of the following:

(i) (–12)3 + (7)3 + (5)3

(ii) (28)3 + (–15)3 + (–13)3

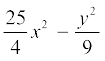

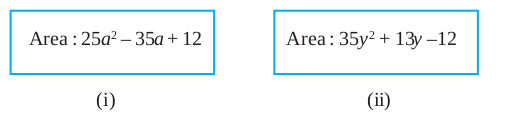

15. Give possible expressions for the length and breadth of each of the following rectangles, in which their areas are given:

16. What are the possible expressions for the dimensions of the cuboids whose volumes are given below?

2.7 Summary

In this chapter, you have studied the following points:

1. A polynomial p(x) in one variable x is an algebraic expression in x of the form

p(x) = anxn + an–1xn – 1 + . . . + a2x2 + a1x + a0,

where a0, a1, a2, . . ., an are constants and an ≠ 0.

a0, a1, a2, . . ., an are respectively the coefficients of x0, x, x2, . . ., xn, and n is called the degree of the polynomial. Each of anxn, an–1 xn–1, ..., a0, with an ≠ 0, is called a term of the polynomial p(x).

2. A polynomial of one term is called a monomial.

3. A polynomial of two terms is called a binomial.

4. A polynomial of three terms is called a trinomial.

5. A polynomial of degree one is called a linear polynomial.

6. A polynomial of degree two is called a quadratic polynomial.

7. A polynomial of degree three is called a cubic polynomial.

8. A real number ‘a’ is a zero of a polynomial p(x) if p(a) = 0. In this case, a is also called a root of the equation p(x) = 0.

9. Every linear polynomial in one variable has a unique zero, a non-zero constant polynomial has no zero, and every real number is a zero of the zero polynomial.

10. Remainder Theorem : If p(x) is any polynomial of degree greater than or equal to 1 and p(x) is divided by the linear polynomial x – a, then the remainder is p(a).

11. Factor Theorem : x – a is a factor of the polynomial p(x), if p(a) = 0. Also, if x – a is a factor of p(x), then p(a) = 0.

12. (x + y + z)2 = x2 + y2 + z2 + 2xy + 2yz + 2zx

13. (x + y)3 = x3 + y3 + 3xy(x + y)

14. (x – y)3 = x3 – y3 – 3xy(x – y)

15. x3 + y3 + z3 – 3xyz = (x + y + z) (x2 + y2 + z2 – xy – yz – zx)