Table of Contents

Chapter 6

Lines and Angles

6.1 Introduction

In Chapter 5, you have studied that a minimum of two points are required to draw a line. You have also studied some axioms and, with the help of these axioms, you proved some other statements. In this chapter, you will study the properties of the angles formed when two lines intersect each other, and also the properties of the angles formed when a line intersects two or more parallel lines at distinct points. Further you will use these properties to prove some statements using deductive reasoning (see Appendix 1). You have already verified these statements through some activities in the earlier classes.

In your daily life, you see different types of angles formed between the edges of plane surfaces. For making a similar kind of model using the plane surfaces, you need to have a thorough knowledge of angles. For instance, suppose you want to make a model of a hut to keep in the school exhibition using bamboo sticks. Imagine how you would make it? You would keep some of the sticks parallel to each other, and some sticks would be kept slanted. Whenever an architect has to draw a plan for a multistoried building, she has to draw intersecting lines and parallel lines at different angles. Without the knowledge of the properties of these lines and angles, do you think she can draw the layout of the building?

In science, you study the properties of light by drawing the ray diagrams.

For example, to study the refraction property of light when it enters from one medium to the other medium, you use the properties of intersecting lines and parallel lines. When two or more forces act on a body, you draw the diagram in which forces are represented by directed line segments to study the net effect of the forces on the body. At that time, you need to know the relation between the angles when the rays (or line segments) are parallel to or intersect each other. To find the height of a tower or to find the distance of a ship from the light house, one needs to know the angle formed between the horizontal and the line of sight. Plenty of other examples can be given where lines and angles are used. In the subsequent chapters of geometry, you will be using these properties of lines and angles to deduce more and more useful properties.

Let us first revise the terms and definitions related to lines and angles learnt in earlier classes.

6.2 Basic Terms and Definitions

Recall that a part (or portion) of a line with two end points is called a line-segment and a part of a line with one end point is called a ray. Note that the line segment AB is denoted by  , and its length is denoted by AB. The ray AB is denoted by

, and its length is denoted by AB. The ray AB is denoted by  , and a line is denoted by

, and a line is denoted by  . However, we will not use these symbols, and will denote the line segment AB, ray AB, length AB and line AB by the same symbol, AB. The meaning will be clear from the context. Sometimes small letters l, m, n, etc. will be used to denote lines.

. However, we will not use these symbols, and will denote the line segment AB, ray AB, length AB and line AB by the same symbol, AB. The meaning will be clear from the context. Sometimes small letters l, m, n, etc. will be used to denote lines.

If three or more points lie on the same line, they are called collinear points; otherwise they are called non-collinear points.

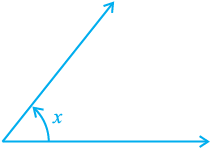

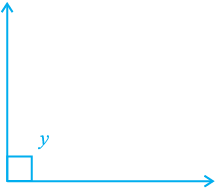

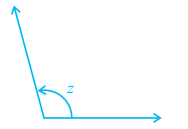

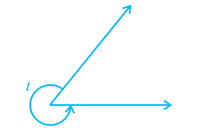

Recall that an angle is formed when two rays originate from the same end point. The rays making an angle are called the arms of the angle and the end point is called the vertex of the angle. You have studied different types of angles, such as acute angle, right angle, obtuse angle, straight angle and reflex angle in earlier classes

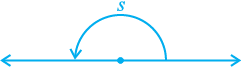

(see Fig. 6.1).

(iii) obtuse angle : 90° < z < 180°

(v) reflex angle : 180° < t < 360°

(iv) straight angle : s = 180°

Fig. 6.1 : Types of Angles

An acute angle measures between 0° and 90°, whereas a right angle is exactly equal to 90°. An angle greater than 90° but less than 180° is called an obtuse angle. Also, recall that a straight angle is equal to 180°. An angle which is greater than 180° but less than 360° is called a reflex angle. Further, two angles whose sum is 90° are called complementary angles, and two angles whose sum is 180° are called supplementary angles.

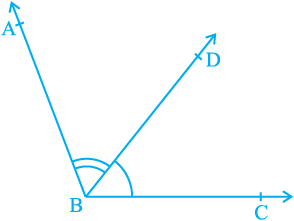

You have also studied about adjacent angles in the earlier classes (see Fig. 6.2).

Fig. 6.2 : Adjacent angles

Two angles are adjacent, if they have a common vertex, a common arm and their non-common arms are on different sides of the common arm. In

Fig. 6.2, ∠ ABD and ∠ DBC are adjacent angles. Ray BD is their common arm and point B is their common vertex. Ray BA and ray BC are non common arms. Moreover, when two angles are adjacent, then their sum is always equal to the angle formed by the two non-common arms. So, we can write

∠ ABC = ∠ ABD + ∠ DBC.

Note that ∠ ABC and ∠ ABD are not adjacent angles. Why? Because their non-common arms BD and BC lie on the same side of the common arm BA.

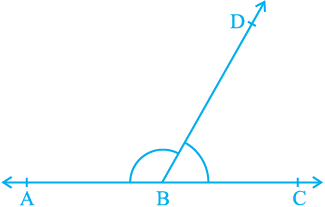

Fig. 6.3 : Linear pair of angles

If the non-common arms BA and BC in

Fig. 6.2, form a line then it will look like Fig. 6.3. In this case, ∠ ABD and ∠ DBC are called linear pair of angles.

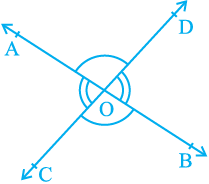

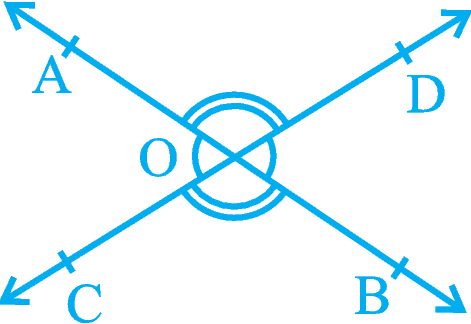

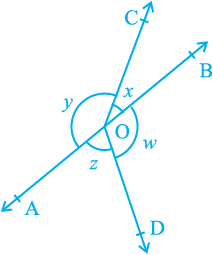

You may also recall the vertically opposite angles formed when two lines, say AB and CD, intersect each other, say at the point O (see Fig. 6.4).There are two pairs of vertically opposite angles.

Fig. 6.4 : Vertically opposite angles

One pair is ∠ AOD and ∠ BOC. Can you find the other pair?

6.3 Intersecting Lines and Non-intersecting Lines

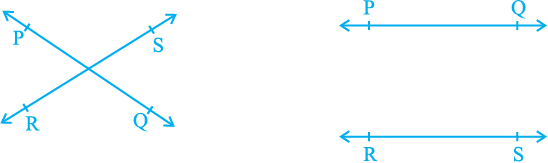

Draw two different lines PQ and RS on a paper. You will see that you can draw them in two different ways as shown in Fig. 6.5 (i) and Fig. 6.5 (ii).

(i) Intersecting lines (ii) Non-intersecting (parallel) lines

Fig. 6.5 : Different ways of drawing two lines

Recall the notion of a line, that it extends indefinitely in both directions. Lines PQ and RS in Fig. 6.5 (i) are intersecting lines and in Fig. 6.5 (ii) are parallel lines. Note that the lengths of the common perpendiculars at different points on these parallel lines is the same. This equal length is called the distance between two parallel lines.

6.4 Pairs of Angles

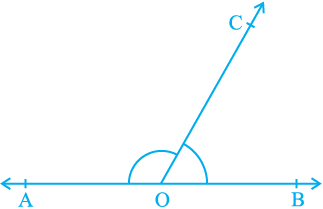

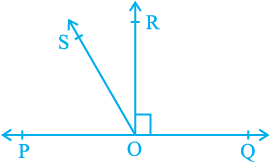

In Section 6.2, you have learnt the definitions of some of the pairs of angles such as complementary angles, supplementary angles, adjacent angles, linear pair of angles, etc. Can you think of some relations between these angles? Now, let us find out the relation between the angles formed when a ray stands on a line. Draw a figure in which a ray stands on a line as shown in Fig. 6.6.

Fig. 6.6 : Linear pair of angles

Name the line as AB and the ray as OC. What are the angles formed at the point O? They are ∠ AOC, ∠ BOC and ∠ AOB.

Can we write ∠ AOC + ∠ BOC = ∠ AOB? (1)

Yes! (Why? Refer to adjacent angles in Section 6.2)

What is the measure of ∠ AOB? It is 180°. (Why?) (2)

From (1) and (2), can you say that ∠ AOC + ∠ BOC = 180°? Yes! (Why?)

From the above discussion, we can state the following Axiom:

Axiom 6.1 : If a ray stands on a line, then the sum of two adjacent angles so formed is 180°.

Recall that when the sum of two adjacent angles is 180°, then they are called a linear pair of angles.

In Axiom 6.1, it is given that ‘a ray stands on a line’. From this ‘given’, we have concluded that ‘the sum of two adjacent angles so formed is 180°’. Can we write Axiom 6.1 the other way? That is, take the ‘conclusion’ of Axiom 6.1 as ‘given’ and the ‘given’ as the ‘conclusion’. So it becomes:

(A) If the sum of two adjacent angles is 180°, then a ray stands on a line (that is, the non-common arms form a line).

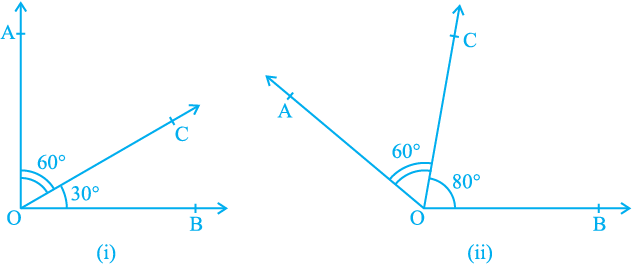

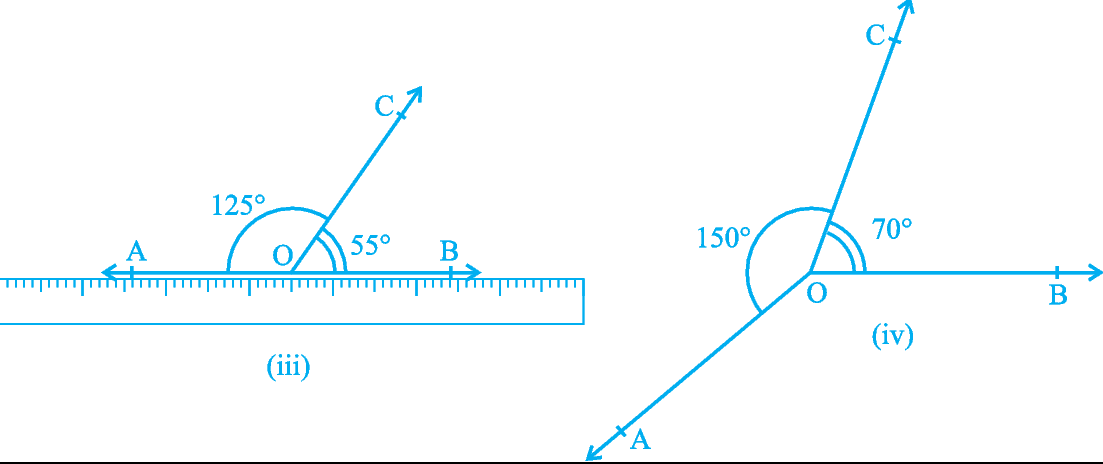

Now you see that the Axiom 6.1 and statement (A) are in a sense the reverse of each others. We call each as converse of the other. We do not know whether the statement (A) is true or not. Let us check. Draw adjacent angles of different measures as shown in Fig. 6.7. Keep the ruler along one of the non-common arms in each case. Does the other non-common arm also lie along the ruler?

Fig. 6.7 : Adjacent angles with different measures

You will find that only in Fig. 6.7 (iii), both the non-common arms lie along the ruler, that is, points A, O and B lie on the same line and ray OC stands on it. Also see that ∠ AOC + ∠ COB = 125° + 55° = 180°. From this, you may conclude that statement (A) is true. So, you can state in the form of an axiom as follows:

Axiom 6.2 : If the sum of two adjacent angles is 180°, then the non-common arms of the angles form a line.

For obvious reasons, the two axioms above together is called the Linear Pair Axiom.

Let us now examine the case when two lines intersect each other.

Recall, from earlier classes, that when two lines intersect, the vertically opposite angles are equal. Let us prove this result now. See Appendix 1 for the ingredients of a proof, and keep those in mind while studying the proof given below.

Theorem 6.1 : If two lines intersect each other, then the vertically opposite angles are equal.

In the statement above, it is given that ‘two lines intersect each other’. So, let AB and CD be two lines intersecting at O as shown in Fig. 6.8. They lead to two pairs of vertically opposite angles, namely,

Fig. 6.8 : Vertically opposite angles

(i) ∠ AOC and ∠ BOD (ii) ∠ AOD and ∠ BOC.

We need to prove that ∠ AOC = ∠ BOD and ∠ AOD = ∠ BOC.

Now, ray OA stands on line CD.

Therefore, ∠ AOC + ∠ AOD = 180° (Linear pair axiom) (1)

Can we write ∠ AOD + ∠ BOD = 180°? Yes! (Why?) (2)

From (1) and (2), we can write

∠ AOC + ∠ AOD = ∠ AOD + ∠ BOD

This implies that ∠ AOC = ∠ BOD (Refer Section 5.2, Axiom 3)

Similarly, it can be proved that ∠ AOD = ∠ BOC

Now, let us do some examples based on Linear Pair Axiom and Theorem 6.1.

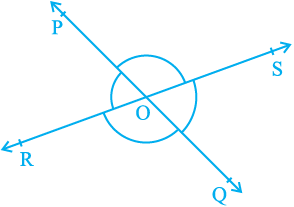

Example 1 : In Fig. 6.9, lines PQ and RS intersect each other at point O. If

∠ POR : ∠ ROQ = 5 : 7, find all the angles.

Solution : ∠ POR + ∠ ROQ = 180°

(Linear pair of angles)

But ∠ POR : ∠ ROQ = 5 : 7 (Given)

Fig. 6.9

Therefore, ∠ POR =  × 180° = 75°

× 180° = 75°

Similarly, ∠ ROQ =  × 180° = 105°

× 180° = 105°

Now, ∠ POS = ∠ ROQ = 105° (Vertically opposite angles)

and ∠ SOQ = ∠ POR = 75° (Vertically opposite angles)

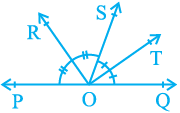

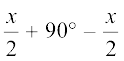

Example 2 : In Fig. 6.10, ray OS stands on a line POQ. Ray OR and ray OT are angle bisectors of ∠ POS and ∠ SOQ, respectively. If ∠ POS = x, find ∠ ROT.

Solution : Ray OS stands on the line POQ.

Therefore, ∠ POS + ∠ SOQ = 180°

But, ∠ POS = x

Therefore, x + ∠ SOQ = 180°

So, ∠ SOQ = 180° – x

Fig. 6.10

∠ ROS =  × ∠ POS

× ∠ POS

=  × x =

× x =

Similarly, ∠ SOT =  × ∠ SOQ

× ∠ SOQ

=  × (180° – x)

× (180° – x)

=

Now, ∠ ROT = ∠ ROS + ∠ SOT

=

= 90°

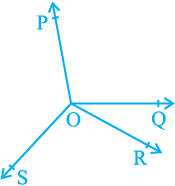

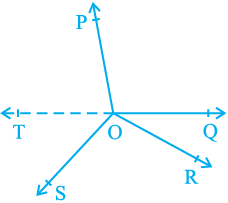

Example 3 : In Fig. 6.11, OP, OQ, OR and OS are four rays. Prove that ∠ POQ + ∠ QOR + ∠ SOR + ∠ POS = 360°.

Solution : In Fig. 6.11, you need to produce any of the rays OP, OQ, OR or OS backwards to a point. Let us produce ray OQ backwards to a point T so that TOQ is a line (see Fig. 6.12).

Fig. 6.11

Now, ray OP stands on line TOQ.

Therefore, ∠ TOP + ∠ POQ = 180° (1)

(Linear pair axiom)

Similarly, ray OS stands on line TOQ.

Therefore, ∠ TOS + ∠ SOQ = 180° (2)

But ∠ SOQ = ∠ SOR + ∠ QOR

Fig. 6.12

So, (2) becomes

∠ TOS + ∠ SOR + ∠ QOR =180° (3)

Now, adding (1) and (3), you get

∠ TOP + ∠ POQ + ∠ TOS + ∠ SOR + ∠ QOR = 360° (4)

But ∠ TOP + ∠ TOS = ∠ POS

Therefore, (4) becomes

∠ POQ + ∠ QOR + ∠ SOR + ∠ POS = 360°

Exercise 6.1

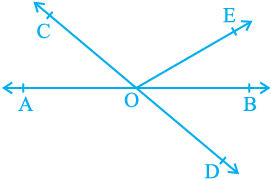

1. In Fig. 6.13, lines AB and CD intersect at O. If

∠ AOC + ∠ BOE = 70° and ∠ BOD = 40°, find

∠ BOE and reflex ∠ COE.

Fig. 6.13

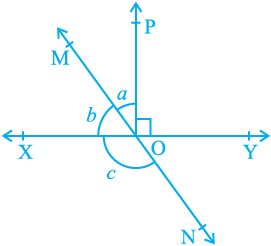

2. In Fig. 6.14, l

ines XY and MN intersect at O. If

∠ POY = 90° and a : b = 2 : 3, find c.

Fig. 6.14

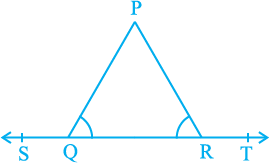

3. In Fig. 6.15, ∠ PQR = ∠ PRQ, then prove that

∠ PQS = ∠ PRT.

Fig. 6.15

4. In Fig. 6.16, if x + y = w + z, then prove that AOB is a line.

Fig. 6.16

5. In Fig. 6.17, POQ is a line. Ray OR is perpendicular to line PQ. OS is another ray lying between rays OP and OR.

Prove that ∠ ROS =  (∠ QOS – ∠ POS).

(∠ QOS – ∠ POS).

Fig. 6.17

6. It is given that ∠ XYZ = 64° and XY is produced to point P. Draw a figure from the given information. If ray YQ bisects ∠ ZYP, find ∠ XYQ and reflex ∠ QYP.

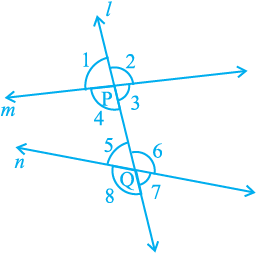

6.5 Parallel Lines and a Transversal

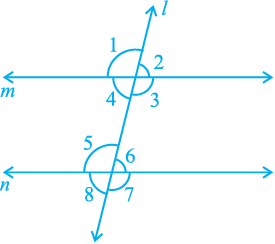

Recall that a line which intersects two or more lines at distinct points is called a transversal (see Fig. 6.18). Line l intersects lines m and n at points P and Q respectively. Therefore, line l is a transversal for lines m and n. Observe that four angles are formed at each of the points P and Q.

Fig. 6.18

Let us name these angles as ∠ 1, ∠ 2, . . ., ∠ 8 as shown in Fig. 6.18.

∠ 1, ∠ 2, ∠ 7 and ∠ 8 are called exterior angles, while ∠ 3, ∠ 4, ∠ 5 and ∠ 6 are called interior angles.

Recall that in the earlier classes, you have named some pairs of angles formed when a transversal intersects two lines. These are as follows:

(a) Corresponding angles :

(i) ∠ 1 and ∠ 5 (ii) ∠ 2 and ∠ 6

(iii) ∠ 4 and ∠ 8 (iv) ∠ 3 and ∠ 7

(b) Alternate interior angles :

(i) ∠ 4 and ∠ 6 (ii) ∠ 3 and ∠ 5

(c) Alternate exterior angles:

(i) ∠ 1 and ∠ 7 (ii) ∠ 2 and ∠ 8

(d) Interior angles on the same side of the transversal:

(i) ∠ 4 and ∠ 5 (ii) ∠ 3 and ∠ 6

Interior angles on the same side of the transversal are also referred to as consecutive interior angles or allied angles or co-interior angles. Further, many a times, we simply use the words alternate angles for alternate interior angles.

Fig. 6.19

Now, let us find out the relation between the angles in these pairs when line m is parallel to line n. You know that the ruled lines of your notebook are parallel to each other. So, with ruler and pencil, draw two parallel lines along any two of these lines and a transversal to intersect them as shown in Fig. 6.19.

Now, measure any pair of corresponding angles and find out the relation between them. You may find that : ∠ 1 = ∠ 5, ∠ 2 = ∠ 6, ∠ 4 = ∠ 8 and ∠ 3 = ∠ 7. From this, you may conclude the following axiom.

Axiom 6.3 : If a transversal intersects two parallel lines, then each pair of corresponding angles is equal.

Axiom 6.3 is also referred to as the corresponding angles axiom. Now, let us discuss the converse of this axiom which is as follows:

If a transversal intersects two lines such that a pair of corresponding angles is equal, then the two lines are parallel.

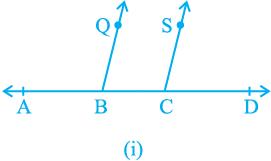

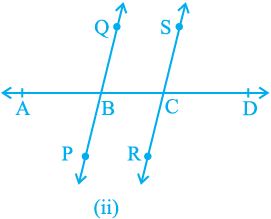

Does this statement hold true? It can be verified as follows: Draw a line AD and mark points B and C on it. At B and C, construct ∠ ABQ and ∠ BCS equal to each other as shown in Fig. 6.20 (i).

Fig. 6.20

Produce QB and SC on the other side of AD to form two lines PQ and RS

[see Fig. 6.20 (ii)]. You may observe that the two lines do not intersect each other. You may also draw common perpendiculars to the two lines PQ and RS at different points and measure their lengths. You will find it the same everywhere. So, you may conclude that the lines are parallel. Therefore, the converse of corresponding angles axiom is also true. So, we have the following axiom:

Axiom 6.4 : If a transversal intersects two lines such that a pair of corresponding angles is equal, then the two lines are parallel to each other.

Can we use corresponding angles axiom to find out the relation between the alternate interior angles when a transversal intersects two parallel lines?

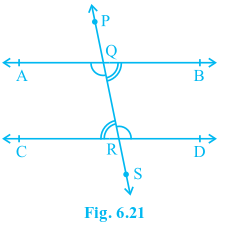

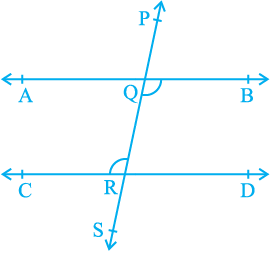

In Fig. 6.21,transveral PS intersects parallel lines AB and CD at points Q and R respectively.

Is ∠ BQR = ∠ QRC and ∠ AQR = ∠ QRD?

You know that ∠ PQA = ∠ QRC (1)

(Corresponding angles axiom)

Is ∠ PQA = ∠ BQR? Yes! (Why ?) (2)

So, from (1) and (2), you may conclude that

∠ BQR = ∠ QRC.

Similarly, ∠ AQR = ∠ QRD.

This result can be stated as a theorem given below:

Theorem 6.2 : If a transversal intersects two parallel lines, then each pair of alternate interior angles is equal.

Now, using the converse of the corresponding angles axiom, can we show the two lines parallel if a pair of alternate interior angles is equal? In Fig. 6.22, the transversal PS intersects lines AB and CD at points Q and R respectively such that

∠ BQR = ∠ QRC.

Fig. 6.22

Is AB || CD?

∠ BQR = ∠ PQA (Why?) (1)

But, ∠ BQR = ∠ QRC (Given) (2)

So, from (1) and (2), you may conclude that

∠ PQA = ∠ QRC

But they are corresponding angles.

So, AB || CD (Converse of corresponding angles axiom)

This result can be stated as a theorem given below:

Theorem 6.3 : If a transversal intersects two lines such that a pair of alternate interior angles is equal, then the two lines are parallel.

In a similar way, you can obtain the following two theorems related to interior angles on the same side of the transversal.

Theorem 6.4 : If a transversal intersects two parallel lines, then each pair of interior angles on the same side of the transversal is supplementary.

Theorem 6.5 : If a transversal intersects two lines such that a pair of interior angles on the same side of the transversal is supplementary, then the two lines are parallel.

You may recall that you have verified all the above axioms and theorems in earlier classes through activities. You may repeat those activities here also.

6.6 Lines Parallel to the Same Line

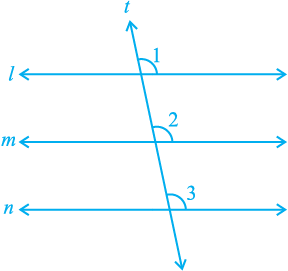

If two lines are parallel to the same line, will they be parallel to each other? Let us check it. See Fig. 6.23 in which line m || line l and line n || line l.

Let us draw a line t transversal for the lines, l, m and n. It is given that

line m || line l and line n || line l.

Therefore, ∠ 1 = ∠ 2 and ∠ 1 = ∠ 3

(Corresponding angles axiom)

So, ∠ 2 = ∠ 3 (Why?)

But ∠ 2 and ∠ 3 are corresponding angles and they are equal.

Therefore, you can say that

Fig. 6.23

Line m || Line n

(Converse of corresponding angles axiom)

This result can be stated in the form of the following theorem:

Theorem 6.6 : Lines which are parallel to the same line are parallel to each other.

Note : The property above can be extended to more than two lines also.

Now, let us solve some examples related to parallel lines.

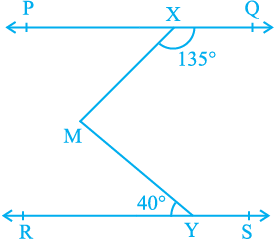

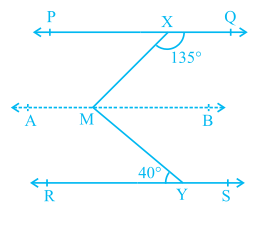

Example 4 : In Fig. 6.24, if PQ || RS, ∠ MXQ = 135° and ∠ MYR = 40°, find ∠ XMY.

Fig. 6.24 Fig. 6.25

Solution : Here, we need to draw a line AB parallel to line PQ, through point M as shown in Fig. 6.25. Now, AB || PQ and PQ || RS.

Therefore, AB || RS (Why?)

Now, ∠ QXM + ∠ XMB = 180°

(AB || PQ, Interior angles on the same side of the transversal XM)

But ∠ QXM = 135°

So, 135° + ∠ XMB = 180°

Therefore, ∠ XMB = 45° (1)

Now, ∠ BMY = ∠ MYR (AB || RS, Alternate angles)

Therefore, ∠ BMY = 40° (2)

Adding (1) and (2), you get

∠ XMB + ∠ BMY = 45° + 40°

That is, ∠ XMY = 85°

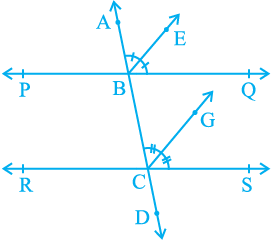

Example 5 : If a transversal intersects two lines such that the bisectors of a pair of corresponding angles are parallel, then prove that the two lines are parallel.

Solution : In Fig. 6.26, a transversal AD intersects two lines PQ and RS at points B and C respectively. Ray BE is the bisector of ∠ ABQ and ray CG is the bisector of

∠ BCS; and BE || CG.

Fig. 6.26

We are to prove that PQ || RS.

It is given that ray BE is the bisector of ∠ ABQ.

Therefore, ∠ ABE =  ∠ ABQ (1)

∠ ABQ (1)

Similarly, ray CG is the bisector of ∠ BCS.

Therefore, ∠ BCG =  ∠ BCS (2)

∠ BCS (2)

But BE || CG and AD is the transversal.

Therefore, ∠ ABE = ∠ BCG

(Corresponding angles axiom) (3)

Substituting (1) and (2) in (3), you get

∠ ABQ =

∠ ABQ =  ∠ BCS

∠ BCS

That is, ∠ ABQ = ∠ BCS

But, they are the corresponding angles formed by transversal AD with PQ and RS; and are equal.

Therefore, PQ || RS (Converse of corresponding angles axiom)

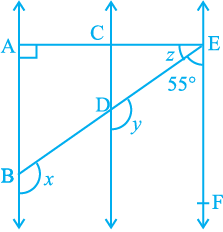

Example 6 : In Fig. 6.27, AB || CD and CD || EF. Also EA ⊥ AB. If ∠ BEF = 55°, find the values of x, y and z.

Fig. 6.27

Solution : y + 55° = 180° (Interior angles on the same side of the transversal ED)

Therefore, y = 180º – 55º = 125º

Again x = y

(AB || CD, Corresponding angles axiom)

Therefore x = 125º

Now, since AB || CD and CD || EF, therefore, AB || EF.

So, ∠ EAB + ∠ FEA = 180° (Interior angles on the same

side of the transversal EA)

Therefore, 90° + z + 55° = 180°

Which gives z = 35°

Exercise 6.2

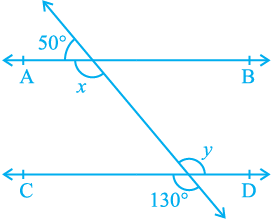

1. In Fig. 6.28, find the values of x and y and then show that AB || CD.

Fig. 6.28

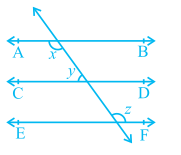

2. In Fig. 6.29, if AB || CD, CD || EF and y : z = 3 : 7, find x.

Fig. 6.29

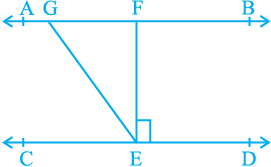

3. In Fig. 6.30, if AB || CD, EF ⊥ CD and∠ GED = 126°, find ∠ AGE, ∠ GEF and ∠ FGE.

Fig. 6.30

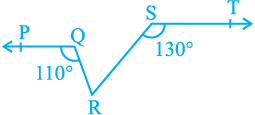

4. In Fig. 6.31, if PQ || ST, ∠ PQR = 110° and

∠ RST = 130°, find ∠ QRS.

[Hint : Draw a line parallel to ST through

point R.]

Fig. 6.31

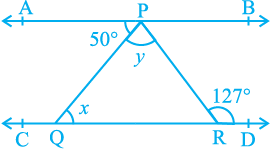

5. In Fig. 6.32, if AB || CD, ∠ APQ = 50° and

∠ PRD = 127°, find x and y.

Fig. 6.32

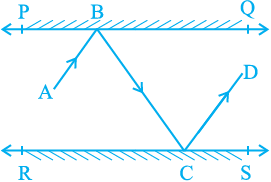

6. In Fig. 6.33, PQ and RS are two mirrors placed parallel to each other. An incident ray AB strikes the mirror PQ at B, the reflected ray moves along the path BC and strikes the mirror RS at C and again reflects back along CD. Prove that

AB || CD.

Fig. 6.33

6.7 Angle Sum Property of a Triangle

In the earlier classes, you have studied through activities that the sum of all the angles of a triangle is 180°. We can prove this statement using the axioms and theorems related to parallel lines.

Theorem 6.7 : The sum of the angles of a triangle is 180º.

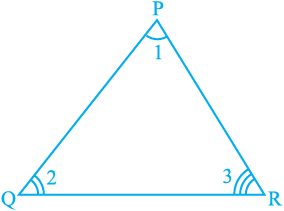

Proof : Let us see what is given in the statement above, that is, the hypothesis and what we need to prove. We are given a triangle PQR and ∠ 1, ∠ 2 and ∠ 3 are the angles of ∆ PQR (see Fig. 6.34).

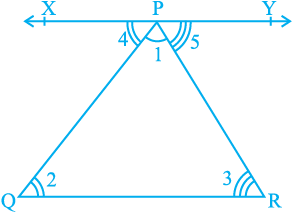

We need to prove that ∠ 1 + ∠ 2 + ∠ 3 = 180°. Let us draw a line XPY parallel to QR through the opposite vertex P, as shown in Fig. 6.35, so that we can use the properties related to parallel lines.

Now, XPY is a line.

Fig. 6.34

Therefore, ∠ 4 + ∠ 1 + ∠ 5 = 180° (1)

But XPY || QR and PQ, PR are transversals.

So, ∠ 4 = ∠ 2 and ∠ 5 = ∠ 3

(Pairs of alternate angles)

Substituting ∠ 4 and ∠ 5 in (1), we get

∠ 2 + ∠ 1 + ∠ 3 = 180°

That is, ∠ 1 + ∠ 2 + ∠ 3 = 180°

Fig. 6.35

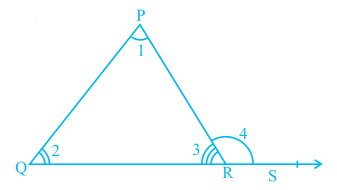

Recall that you have studied about the formation of an exterior angle of a triangle in the earlier classes (see Fig. 6.36). Side QR is produced to point S, ∠ PRS is called an exterior angle of ∆PQR.

Is ∠ 3 + ∠ 4 = 180°? (Why?) (1)

Also, see that

∠ 1 + ∠ 2 + ∠ 3 = 180° (Why?) (2)

From (1) and (2), you can see that

∠ 4 = ∠ 1 + ∠ 2.

This result can be stated in the form of a theorem as given below:

Fig. 6.36

Theorem 6.8 : If a side of a triangle is produced, then the exterior angle so formed is equal to the sum of the two interior opposite angles.

It is obvious from the above theorem that an exterior angle of a triangle is greater than either of its interior apposite angles.

Now, let us take some examples based on the above theorems.

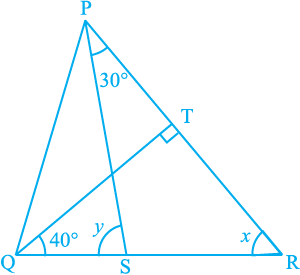

Example 7 : In Fig. 6.37, if QT ⊥ PR, ∠ TQR = 40° and ∠ SPR = 30°, find x and y.

Fig. 6.37

Solution : In ∆ TQR, 90° + 40° + x = 180°

(Angle sum property of a triangle)

Therefore, x = 50°

Now, y = ∠ SPR + x (Theorem 6.8)

Therefore, y = 30° + 50°= 80°

Example 8 : In Fig. 6.38, the sides AB and AC of ∆ABC are produced to points E and D respectively. If bisectors BO and CO of ∠ CBE and ∠ BCD respectively meet at point O,then prove that ∠ BOC = 90° –  ∠ BAC.

∠ BAC.

Fig. 6.38

Solution : Ray BO is the bisector of ∠ CBE.

Therefore, ∠ CBO =  ∠ CBE

∠ CBE

=  (180° – y)

(180° – y)

= 90° –  (1)

(1)

Similarly, ray CO is the bisector of ∠ BCD.

Therefore, ∠ BCO =  ∠ BCD

∠ BCD

=  (180° – z)

(180° – z)

= 90° –  (2)

(2)

In ∆ BOC, ∠ BOC + ∠ BCO + ∠ CBO = 180° (3)

Substituting (1) and (2) in (3), you get

∠ BOC + 90° –  + 90° –

+ 90° –  = 180°

= 180°

So, ∠ BOC =  +

+

or, ∠ BOC =  (y + z) (4)

(y + z) (4)

But, x + y + z = 180° (Angle sum property of a triangle)

Therefore, y + z = 180° – x

Therefore, (4) becomes

∠ BOC =  (180° – x)

(180° – x)

= 90° –

= 90° –  ∠ BAC

∠ BAC

Exercise 6.3

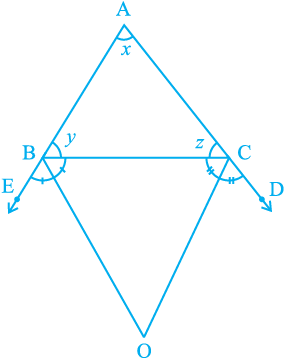

1. In Fig. 6.39, sides QP and RQ of ∆ PQR are produced to points S and T respectively. If ∠ SPR = 135° and ∠ PQT = 110°, find ∠ PRQ.

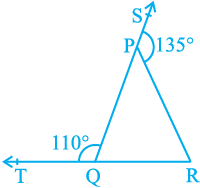

2. In Fig. 6.40, ∠ X = 62°, ∠ XYZ = 54°. If YO and ZO are the bisectors of ∠ XYZ and

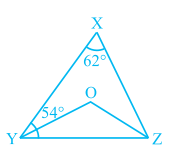

∠ XZY respectively of ∆ XYZ, find ∠ OZY and ∠ YOZ.

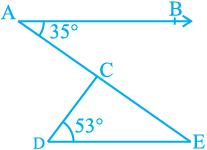

3. In Fig. 6.41, if AB || DE, ∠ BAC = 35° and ∠ CDE = 53°, find ∠ DCE.

Fig. 6.39

Fig. 6.40

Fig. 6.41

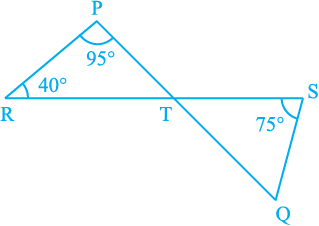

4. In Fig. 6.42, if lines PQ and RS intersect at point T, such that ∠ PRT = 40°, ∠ RPT = 95° and ∠ TSQ = 75°, find ∠ SQT.

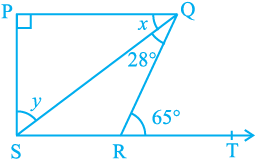

5. In Fig. 6.43, if PQ ⊥ PS, PQ || SR, ∠ SQR = 28° and ∠ QRT = 65°, then find the values of x and y.

Fig. 6.42

Fig. 6.43

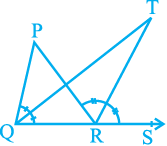

6. In Fig. 6.44, the side QR of ∆ PQR is produced to a point S. If the bisectors of ∠ PQR and

∠ PRS meet at point T, then prove that

∠ QTR =  ∠ QPR.

∠ QPR.

Fig. 6.44

In this chapter, you have studied the following points:

1. If a ray stands on a line, then the sum of the two adjacent angles so formed is 180° and vice-versa. This property is called as the Linear pair axiom.

2. If two lines intersect each other, then the vertically opposite angles are equal.

3. If a transversal intersects two parallel lines, then

(i) each pair of corresponding angles is equal,

(ii) each pair of alternate interior angles is equal,

(iii) each pair of interior angles on the same side of the transversal is supplementary.

4. If a transversal intersects two lines such that, either

(i) any one pair of corresponding angles is equal, or

(ii) any one pair of alternate interior angles is equal, or

(iii) any one pair of interior angles on the same side of the transversal is supplementary, then the lines are parallel.

5. Lines which are parallel to a given line are parallel to each other.

6. The sum of the three angles of a triangle is 180°.

7. If a side of a triangle is produced, the exterior angle so formed is equal to the sum of the two interior opposite angles.