Table of Contents

Chapter 7

Triangles

7.1 Introduction

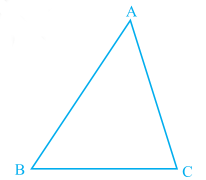

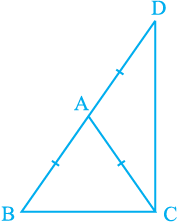

You have studied about triangles and their various properties in your earlier classes. You know that a closed figure formed by three intersecting lines is called a triangle. (‘Tri’ means ‘three’). A triangle has three sides, three angles and three vertices. For example, in triangle ABC, denoted as ∆ ABC (see Fig. 7.1); AB, BC, CA are the three sides, ∠ A, ∠ B, ∠ C are the three angles and A, B, C are three vertices.

In Chapter 6, you have also studied some properties of triangles. In this chapter, you will study in details about the congruence of triangles, rules of congruence, some more properties of triangles and inequalities in a triangle. You have already verified most of these properties in earlier classes. We will now prove some of them.

Fig. 7.1

7.2 Congruence of Triangles

You must have observed that two copies of your photographs of the same size are identical. Similarly, two bangles of the same size, two ATM cards issued by the same bank are identical. You may recall that on placing a one rupee coin on another minted in the same year, they cover each other completely.

Do you remember what such figures are called? Indeed they are called congruent figures (‘congruent’ means equal in all respects or figures whose shapes and sizes are both the same).

Now, draw two circles of the same radius and place one on the other. What do you observe? They cover each other completely and we call them as congruent circles.

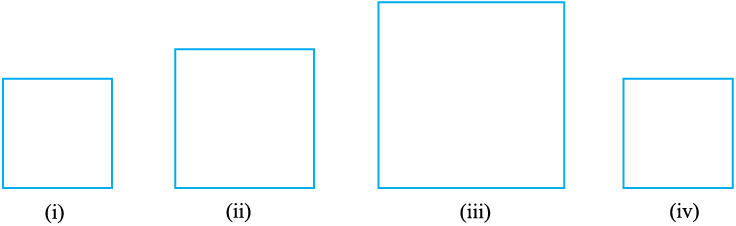

Repeat this activity by placing one square on the other with sides of the same measure (see Fig. 7.2) or by placing two equilateral triangles of equal sides on each other. You will observe that the squares are congruent to each other and so are the equilateral triangles.

Fig. 7.2

You may wonder why we are studying congruence. You all must have seen the ice tray in your refrigerator. Observe that the moulds for making ice are all congruent. The cast used for moulding in the tray also has congruent depressions (may be all are rectangular or all circular or all triangular). So, whenever identical objects have to be produced, the concept of congruence is used in making the cast.

Sometimes, you may find it difficult to replace the refill in your pen by a new one and this is so when the new refill is not of the same size as the one you want to remove. Obviously, if the two refills are identical or congruent, the new refill fits.

So, you can find numerous examples where congruence of objects is applied in daily life situations.

Can you think of some more examples of congruent figures?

Now, which of the following figures are not congruent to the square in

Fig 7.3 (i) :

Fig. 7.3

The large squares in Fig. 7.3 (ii) and (iii) are obviously not congruent to the one in Fig 7.3 (i), but the square in Fig 7.3 (iv) is congruent to the one given in Fig 7.3 (i).

Let us now discuss the congruence of two triangles.

You already know that two triangles are congruent if the sides and angles of one triangle are equal to the corresponding sides and angles of the other triangle.

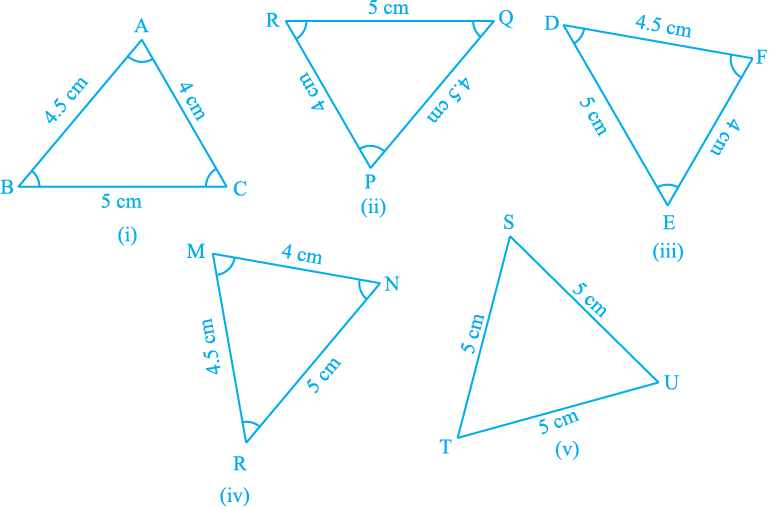

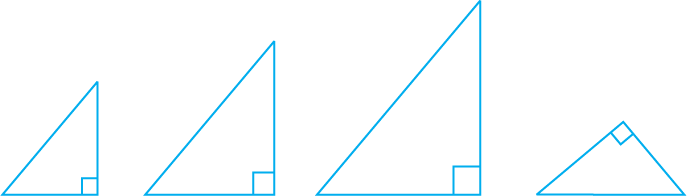

Now, which of the triangles given below are congruent to triangle ABC in Fig. 7.4 (i)?

Fig. 7.4

Cut out each of these triangles from Fig. 7.4 (ii) to (v) and turn them around and try to cover ∆ ABC. Observe that triangles in Fig. 7.4 (ii), (iii) and (iv) are congruent to ∆ ABC while ∆ TSU of Fig 7.4 (v) is not congruent to ∆ ABC.

If ∆ PQR is congruent to ∆ ABC, we write ∆ PQR ≅ ∆ ABC.

Notice that when ∆ PQR ≅ ∆ ABC, then sides of ∆ PQR fall on corresponding equal sides of ∆ ABC and so is the case for the angles.

That is, PQ covers AB, QR covers BC and RP covers CA; ∠ P covers ∠ A, ∠ Q covers ∠ B and ∠ R covers ∠ C. Also, there is a one-one correspondence between the vertices. That is, P corresponds to A, Q to B, R to C and so on which is written as

P ↔ A, Q ↔ B, R ↔ C

Note that under this correspondence, ∆ PQR ≅ ∆ ABC; but it will not be correct to write ∆QRP ≅ ∆ ABC. Similarly, for Fig. 7.4 (iii),

FD ↔ AB, DE ↔ BC and EF ↔ CA

and F ↔ A, D ↔ B and E ↔ C

So, ∆ FDE ≅ ∆ ABC but writing ∆ DEF ≅ ∆ ABC is not correct.

Give the correspondence between the triangle in Fig. 7.4 (iv) and ∆ ABC.

So, it is necessary to write the correspondence of vertices correctly for writing of congruence of triangles in symbolic form.

Note that in congruent triangles corresponding parts are equal and we write in short ‘CPCT’ for corresponding parts of congruent triangles.

7.3 Criteria for Congruence of Triangles

In earlier classes, you have learnt four criteria for congruence of triangles. Let us recall them.

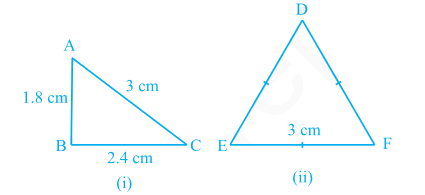

Draw two triangles with one side 3 cm. Are these triangles congruent? Observe that they are not congruent (see Fig. 7.5).

Fig. 7.5

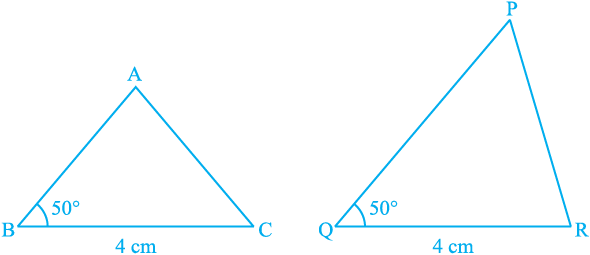

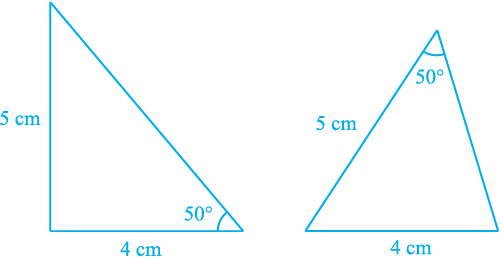

Now, draw two triangles with one side 4 cm and one angle 50° (see Fig. 7.6). Are they congruent?

Fig. 7.6

See that these two triangles are not congruent.

Repeat this activity with some more pairs of triangles.

So, equality of one pair of sides or one pair of sides and one pair of angles is not sufficient to give us congruent triangles.

What would happen if the other pair of arms (sides) of the equal angles are also equal?

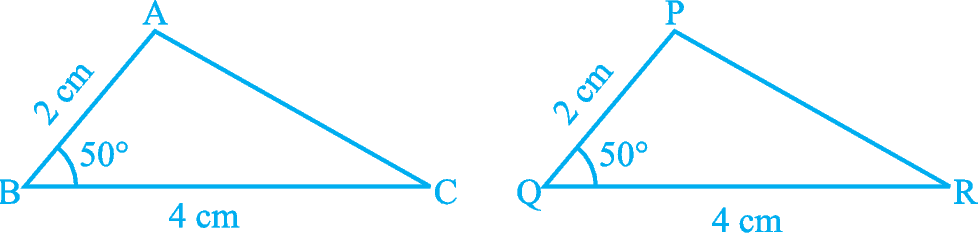

In Fig 7.7, BC = QR, ∠ B = ∠ Q and also, AB = PQ. Now, what can you say about congruence of  ABC and

ABC and  PQR?

PQR?

Recall from your earlier classes that, in this case, the two triangles are congruent. Verify this for ∆ ABC and ∆ PQR in Fig. 7.7.

Repeat this activity with other pairs of triangles. Do you observe that the equality of two sides and the included angle is enough for the congruence of triangles? Yes, it is enough.

Fig. 7.7

This is the first criterion for congruence of triangles.

Axiom 7.1 (SAS congruence rule) : Two triangles are congruent if two sides and the included angle of one triangle are equal to the two sides and the included angle of the other triangle.

This result cannot be proved with the help of previously known results and so it is accepted true as an axiom (see Appendix 1).

Let us now take some examples.

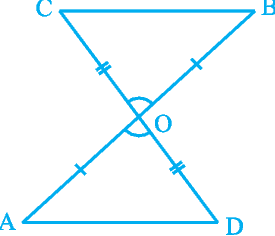

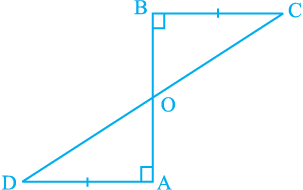

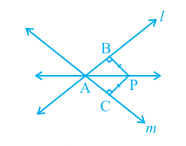

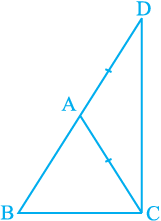

Example 1 : In Fig. 7.8, OA = OB and OD = OC. Show that

(i) ∆ AOD ≅ ∆ BOC and (ii) AD || BC.

Fig. 7.8

Solution : (i) You may observe that in ∆ AOD and ∆ BOC,

OA = OB (Given)

OD = OC

Also, since ∠ AOD and ∠ BOC form a pair of vertically opposite angles, we have

∠ AOD = ∠ BOC.

So, ∆ AOD ≅ ∆ BOC (by the SAS congruence rule)

(ii) In congruent triangles AOD and BOC, the other corresponding parts are also equal.

So, ∠ OAD = ∠ OBC and these form a pair of alternate angles for line segments AD and BC.

Therefore, AD || BC.

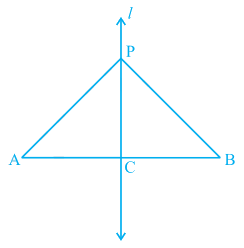

Example 2 : AB is a line segment and line l is its perpendicular bisector. If a point P lies on l, show that P is equidistant from A and B.

Fig. 7.9

Solution : Line l ⊥ AB and passes through C which is the mid-point of AB (see Fig. 7.9). You have to show that PA = PB. Consider ∆ PCA and ∆ PCB.

We have AC = BC (C is the mid-point of AB)

∠ PCA = ∠ PCB = 90° (Given)

PC = PC (Common)

So, ∆ PCA ≅ ∆ PCB (SAS rule)

and so, PA = PB, as they are corresponding sides of congruent triangles.

Now, let us construct two triangles, whose sides are 4 cm and 5 cm and one of the angles is 50° and this angle is not included in between the equal sides (see Fig. 7.10). Are the two triangles congruent?

Fig. 7.10

Notice that the two triangles are not congruent.

Repeat this activity with more pairs of triangles. You will observe that for triangles to be congruent, it is very important that the equal angles are included between the pairs of equal sides.

So, SAS congruence rule holds but not ASS or SSA rule.

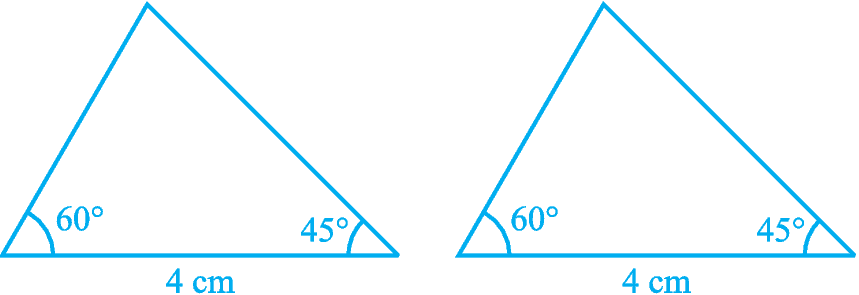

Next, try to construct the two triangles in which two angles are 60° and 45° and the side included between these angles is 4 cm (see Fig. 7.11).

Fig. 7.11

Cut out these triangles and place one triangle on the other. What do you observe?

See that one triangle covers the other completely; that is, the two triangles are congruent. Repeat this activity with more pairs of triangles. You will observe that equality of two angles and the included side is sufficient for congruence of triangles.

This result is the Angle-Side-Angle criterion for congruence and is written as ASA criterion. You have verified this criterion in earlier classes, but let us state and prove this result.

Since this result can be proved, it is called a theorem and to prove it, we use the SAS axiom for congruence.

Theorem 7.1 (ASA congruence rule) : Two triangles are congruent if two angles and the included side of one triangle are equal to two angles and the included side of other triangle.

Proof : We are given two triangles ABC and DEF in which:

∠ B = ∠ E, ∠ C = ∠ F

and BC = EF

We need to prove that ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ DEF

For proving the congruence of the two triangles see that three cases arise.

Case (i) : Let AB = DE (see Fig. 7.12).

Now what do you observe? You may observe that

AB = DE (Assumed)

∠ B = ∠ E (Given)

BC = EF (Given)

So, ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ DEF (By SAS rule)

Fig. 7.12

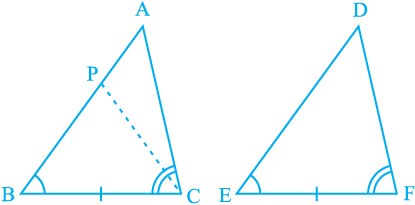

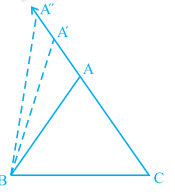

Case (ii) : Let if possible AB > DE. So, we can take a point P on AB such that

PB = DE. Now consider ∆ PBC and ∆ DEF (see Fig. 7.13).

Fig. 7.13

Observe that in ∆ PBC and ∆ DEF,

PB = DE (By construction)

∠ B = ∠ E (Given)

BC = EF (Given)

So, we can conclude that:

∆ PBC ≅ ∆ DEF, by the SAS axiom for congruence.

Since the triangles are congruent, their corresponding parts will be equal.

So, ∠ PCB = ∠ DFE

But, we are given that

∠ ACB = ∠ DFE

So, ∠ ACB = ∠ PCB

Is this possible?

This is possible only if P coincides with A.

or, BA = ED

So, ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ DEF (by SAS axiom)

Case (iii) : If AB < DE, we can choose a point M on DE such that ME = AB and repeating the arguments as given in Case (ii), we can conclude that AB = DE and so, ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ DEF.

Suppose, now in two triangles two pairs of angles and one pair of corresponding sides are equal but the side is not included between the corresponding equal pairs of angles. Are the triangles still congruent? You will observe that they are congruent. Can you reason out why?

You know that the sum of the three angles of a triangle is 180°. So if two pairs of angles are equal, the third pair is also equal (180° – sum of equal angles).

So, two triangles are congruent if any two pairs of angles and one pair of corresponding sides are equal. We may call it as the AAS Congruence Rule.

Now let us perform the following activity :

Draw triangles with angles 40°, 50° and 90°. How many such triangles can you draw?

In fact, you can draw as many triangles as you want with different lengths of sides (see Fig. 7.14).

Fig. 7.14

Observe that the triangles may or may not be congruent to each other.

So, equality of three angles is not sufficient for congruence of triangles. Therefore, for congruence of triangles out of three equal parts, one has to be a side.

Let us now take some more examples.

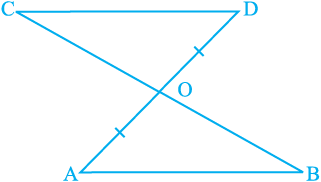

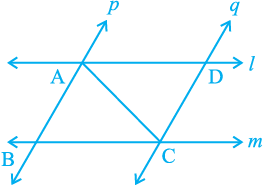

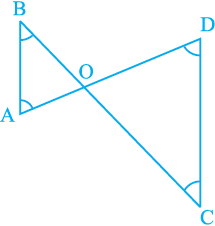

Example 3 : Line-segment AB is parallel to another line-segment CD. O is the

mid-point of AD (see Fig. 7.15). Show that (i) ∆AOB ≅ ∆DOC (ii) O is also the

mid-point of BC.

Solution : (i) Consider ∆ AOB and ∆ DOC.

∠ ABO = ∠ DCO

(Alternate angles as AB || CD

and BC is the transversal)

∠ AOB = ∠ DOC

(Vertically opposite angles)

OA = OD (Given)

Therefore, ∆AOB ≅ ∆DOC (AAS rule)

(ii) OB = OC (CPCT)

So, O is the mid-point of BC.

Fig. 7.15

Exercise 7.1

1. In quadrilateral ACBD,

AC = AD and AB bisects ∠ A

(see Fig. 7.16). Show that ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ ABD.

Fig. 7.16

What can you say about BC and BD?

2. ABCD is a quadrilateral in which AD = BC and

∠ DAB = ∠ CBA (see Fig. 7.17). Prove that

(i) ∆ ABD ≅ ∆ BAC

(ii) BD = AC

(iii) ∠ ABD = ∠ BAC.

Fig. 7.17

3. AD and BC are equal perpendiculars to a line segment AB (see Fig. 7.18). Show that CD bisects AB.

Fig. 7.18

4. l and m are two parallel lines intersected by another pair of parallel lines p and q

(see Fig. 7.19). Show that ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ CDA.

Fig. 7.19

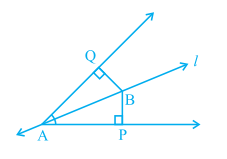

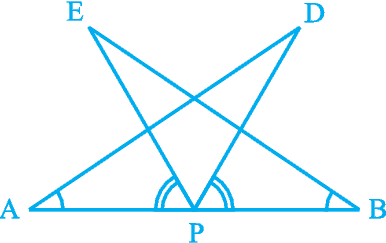

5. Line l is the bisector of an angle ∠ A and B is any point on l. BP and BQ are perpendiculars from B to the arms of ∠ A (see Fig. 7.20).

Show that:

(i) ∆ APB ≅ ∆ AQB

(ii) BP = BQ or B is equidistant from the arms of ∠ A.

Fig. 7.20

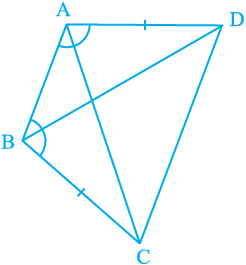

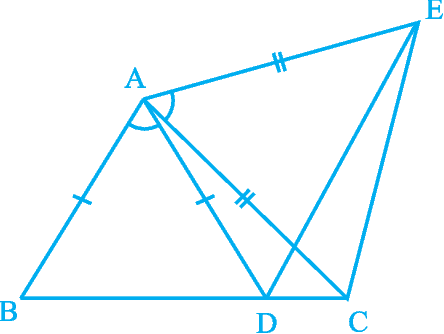

6. In Fig. 7.21, AC = AE, AB = AD and

∠ BAD = ∠ EAC. Show that BC = DE.

Fig. 7.21

7. AB is a line segment and P is its mid-point. D and E are points on the same side of AB such that

∠ BAD = ∠ ABE and ∠ EPA = ∠ DPB

(see Fig. 7.22). Show that

(i) ∆ DAP ≅ ∆ EBP

(ii) AD = BE

Fig. 7.22

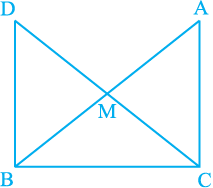

8. In right triangle ABC, right angled at C, M is the mid-point of hypotenuse AB. C is joined to M and produced to a point D such that DM = CM. Point D is joined to point B

(see Fig. 7.23). Show that:

(i) ∆ AMC ≅ ∆ BMD

(ii) ∠ DBC is a right angle.

(iii) ∆ DBC ≅ ∆ ACB

(iv) CM =  AB

AB

Fig. 7.23

7.4 Some Properties of a Triangle

In the above section you have studied two criteria for congruence of triangles. Let us now apply these results to study some properties related to a triangle whose two sides are equal.

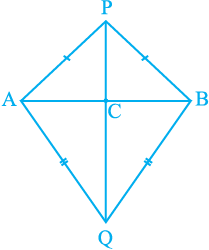

Perform the activity given below:

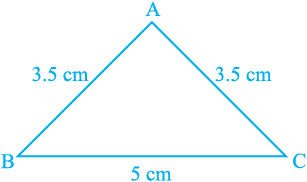

Construct a triangle in which two sides are equal, say each equal to 3.5 cm and the third side equal to 5 cm (see Fig. 7.24). You have done such constructions in earlier classes.

Do you remember what is such a triangle called?

Fig. 7.24

A triangle in which two sides are equal is called an isosceles triangle. So, ∆ ABC of Fig. 7.24 is an isosceles triangle with AB = AC.

Now, measure ∠ B and ∠ C. What do you observe?

Repeat this activity with other isosceles triangles with different sides.

You may observe that in each such triangle, the angles opposite to the equal sides are equal.

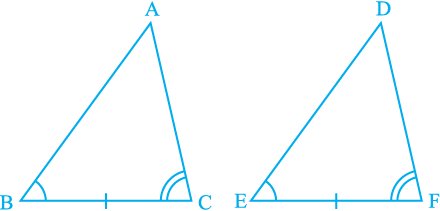

Theorem 7.2 : Angles opposite to equal sides of an isosceles triangle are equal.

This result can be proved in many ways. One of the proofs is given here.

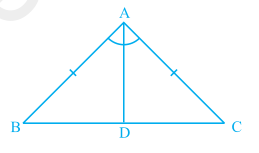

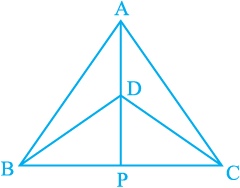

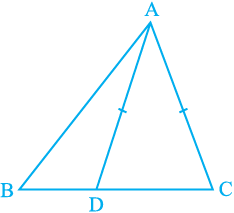

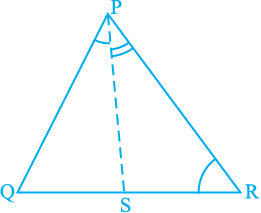

Fig. 7.25

Proof : We are given an isosceles triangle ABC in which AB = AC. We need to prove that

∠ B = ∠ C.

Let us draw the bisector of ∠ A and let D be the point of intersection of this bisector of

∠ A and BC (see Fig. 7.25).

In ∆ BAD and ∆ CAD,

AB = AC (Given)

∠ BAD = ∠ CAD (By construction)

AD = AD (Common)

So, ∆ BAD ≅ ∆ CAD (By SAS rule)

So, ∠ ABD = ∠ ACD, since they are corresponding angles of congruent triangles.

So, ∠ B = ∠ C

Is the converse also true? That is:

If two angles of any triangle are equal, can we conclude that the sides opposite to them are also equal?

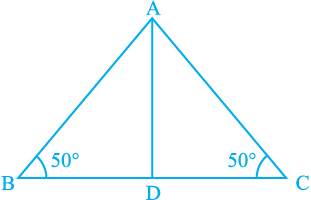

Construct a triangle ABC with BC of any length and ∠ B = ∠ C = 50°. Draw the bisector of ∠ A and let it intersect BC at D (see Fig. 7.26).

Cut out the triangle from the sheet of paper and fold it along AD so that vertex C falls on vertex B.

What can you say about sides AC and AB?

Observe that AC covers AB completely

So, AC = AB

Fig. 7.26

Repeat this activity with some more triangles. Each time you will observe that the sides opposite to equal angles are equal. So we have the following:

Theorem 7.3 : The sides opposite to equal angles of a triangle are equal.

This is the converse of Theorem 7.2.

You can prove this theorem by ASA congruence rule.

Let us take some examples to apply these results.

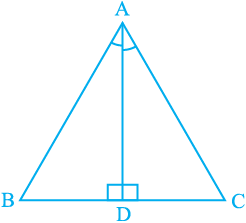

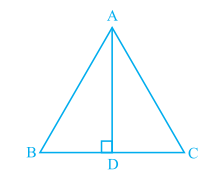

Example 4 : In ∆ ABC, the bisector AD of ∠ A is perpendicular to side BC

(see Fig. 7.27). Show that AB = AC and ∆ ABC is isosceles.

Solution : In ∆ABD and ∆ACD,

Fig. 7.27

∠ BAD = ∠ CAD (Given)

AD = AD (Common)

∠ ADB = ∠ ADC = 90° (Given)

So, ∆ ABD ≅ ∆ ACD (ASA rule)

So, AB = AC (CPCT)

or, ∆ ABC is an isosceles triangle.

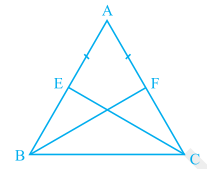

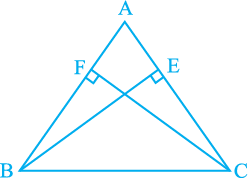

Example 5 : E and F are respectively the mid-points of equal sides AB and AC of ∆ ABC (see Fig. 7.28). Show that BF = CE.

Solution : In ∆ ABF and ∆ ACE,

AB = AC (Given)

∠ A = ∠ A (Common)

AF = AE (Halves of equal sides)

So, ∆ ABF ≅ ∆ ACE (SAS rule)

Therefore, BF = CE (CPCT)

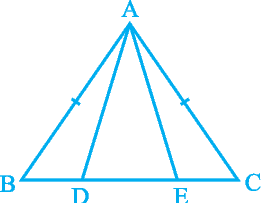

Example 6 : In an isosceles triangle ABC with AB = AC, D and E are points on BC such that BE = CD (see Fig. 7.29).Show that AD = AE.

Fig. 7.29

Solution : In ∆ ABD and ∆ ACE,

AB = AC (Given) (1)

∠ B = ∠ C

(Angles opposite to equal sides) (2)

Also, BE = CD

So, BE – DE = CD – DE

That is, BD = CE (3)

So, ∆ ABD ≅ ∆ ACE

(Using (1), (2), (3) and SAS rule).

This gives AD = AE (CPCT)

Exercise 7.2

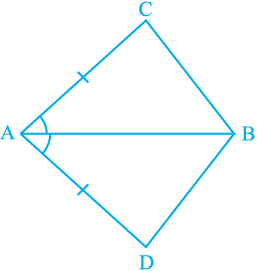

1. In an isosceles triangle ABC, with AB = AC, the bisectors of ∠ B and ∠ C intersect each other at O. Join A to O. Show that :

(i) OB = OC (ii) AO bisects ∠ A

2. In ∆ ABC, AD is the perpendicular bisector of BC (see Fig. 7.30). Show that ∆ ABC is an isosceles triangle in which AB = AC.

Fig. 7.30

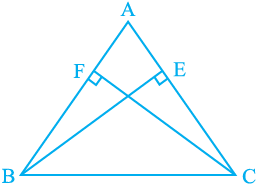

3. ABC is an isosceles triangle in which altitudes BE and CF are drawn to equal sides AC and AB respectively (see Fig. 7.31). Show that these altitudes are equal.

Fig. 7.31

4. ABC is a triangle in which altitudes BE and CF to sides AC and AB are equal (see Fig. 7.32).Show that

(i) ∆ ABE ≅ ∆ ACF

(ii) AB = AC, i.e., ABC is an isosceles triangle.

Fig. 7.32

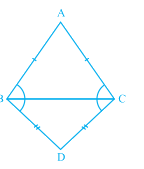

5. ABC and DBC are two isosceles triangles on the same base BC (see Fig. 7.33).Show that

∠ ABD = ∠ ACD.

Fig. 7.33

6. ∆ABC is an isosceles triangle in which AB = AC. Side BA is produced to D such that AD = AB (see Fig. 7.34).Show that ∠ BCD is a right angle.

Fig. 7.34

7. ABC is a right angled triangle in which ∠ A = 90° and AB = AC. Find ∠ B and ∠ C.

8. Show that the angles of an equilateral triangle are 60° each.

7.5 Some More Criteria for Congruence of Triangles

You have seen earlier in this chapter that equality of three angles of one triangle to three angles of the other is not sufficient for the congruence of the two triangles. You may wonder whether equality of three sides of one triangle to three sides of another triangle is enough for congruence of the two triangles. You have already verified in earlier classes that this is indeed true.

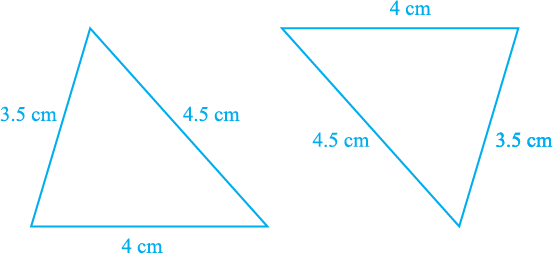

To be sure, construct two triangles with sides 4 cm, 3.5 cm and 4.5 cm

(see Fig. 7.35). Cut them out and place them on each other. What do you observe? They cover each other completely, if the equal sides are placed on each other. So, the triangles are congruent.

Fig. 7.35

Repeat this activity with some more triangles. We arrive at another rule for congruence.

Theorem 7.4 (SSS congruence rule) : If three sides of one triangle are equal to the three sides of another triangle, then the two triangles are congruent.

This theorem can be proved using a suitable construction.

You have already seen that in the SAS congruence rule, the pair of equal angles has to be the included angle between the pairs of corresponding pair of equal sides and if this is not so, the two triangles may not be congruent.

Perform this activity:

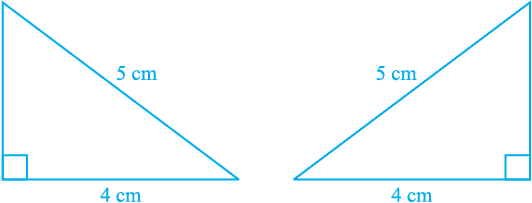

Construct two right angled triangles with hypotenuse equal to 5 cm and one side equal to 4 cm each (see Fig. 7.36).

Fig. 7.36

Cut them out and place one triangle over the other with equal side placed on each other. Turn the triangles, if necessary. What do you observe?

The two triangles cover each other completely and so they are congruent. Repeat this activity with other pairs of right triangles. What do you observe?

You will find that two right triangles are congruent if one pair of sides and the hypotenuse are equal. You have verified this in earlier classes.

Note that, the right angle is not the included angle in this case.

So, you arrive at the following congruence rule:

Theorem 7.5 (RHS congruence rule) : If in two right triangles the hypotenuse and one side of one triangle are equal to the hypotenuse and one side of the other triangle, then the two triangles are congruent.

Note that RHS stands for Right angle - Hypotenuse - Side.

Let us now take some examples.

Example 7 : AB is a line-segment. P and Q are points on opposite sides of AB such that each of them is equidistant from the points A and B (see Fig. 7.37). Show that the line PQ is the perpendicular bisector of AB.

Fig. 7.37

Solution : You are given that PA = PB and

QA = QB and you are to show that PQ ⊥ AB and PQ bisects AB. Let PQ intersect AB at C.

Can you think of two congruent triangles in this figure?

Let us take ∆ PAQ and ∆ PBQ.

In these triangles,

AP = BP (Given)

AQ = BQ (Given)

PQ = PQ (Common)

So, ∆ PAQ ≅ ∆ PBQ (SSS rule)

Therefore, ∠ APQ = ∠ BPQ (CPCT).

Now let us consider  PAC and

PAC and  PBC.

PBC.

You have : AP = BP (Given)

∠ APC = ∠ BPC (∠ APQ = ∠ BPQ proved above)

PC = PC (Common)

So, ∆ PAC ≅ ∆ PBC (SAS rule)

Therefore, AC = BC (CPCT) (1)

and ∠ ACP = ∠ BCP (CPCT)

Also, ∠ ACP + ∠ BCP = 180° (Linear pair)

So, 2∠ ACP = 180°

or, ∠ ACP = 90° (2)

From (1) and (2), you can easily conclude that PQ is the perpendicular bisector of AB.

[Note that, without showing the congruence of  PAQ and

PAQ and  PBQ, you cannot show that

PBQ, you cannot show that  PAC

PAC

PBC even though AP = BP (Given)

PBC even though AP = BP (Given)

PC = PC (Common)

and ∠ PAC = ∠ PBC (Angles opposite to equal sides in

∆APB)

It is because these results give us SSA rule which is not always valid or true for congruence of triangles. Also the angle is not included between the equal pairs of sides.]

Let us take some more examples.

Example 8 : P is a point equidistant from two lines l and m intersecting at point A

(see Fig. 7.38). Show that the line AP bisects the angle between them.

Solution : You are given that lines l and m intersect each other at A. Let PB ⊥ l,

PC ⊥ m. It is given that PB = PC.

You are to show that ∠ PAB = ∠ PAC.

Let us consider ∆ PAB and ∆ PAC. In these two triangles,

Fig. 7.38

PB = PC (Given)

∠ PBA = ∠ PCA = 90° (Given)

PA = PA (Common)

So, ∆ PAB ≅ ∆ PAC (RHS rule)

So, ∠ PAB = ∠ PAC (CPCT)

Note that this result is the converse of the result proved in Q.5 of Exercise 7.1.

Exercise 7.3

1. ∆ ABC and ∆ DBC are two isosceles triangles on the same base BC and vertices A and D are on the same side of BC (see Fig. 7.39). If AD is extended to intersect BC at P, show that

Fig. 7.39

(i) ∆ ABD ≅ ∆ ACD

(ii) ∆ ABP ≅ ∆ ACP

(iii) AP bisects ∠ A as well as ∠ D.

(iv) AP is the perpendicular bisector of BC.

2. AD is an altitude of an isosceles triangle ABC in which AB = AC. Show that

(i) AD bisects BC (ii) AD bisects ∠ A.

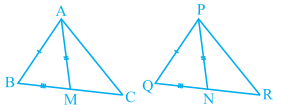

3. Two sides AB and BC and median AM of one triangle ABC are respectively equal to sides PQ and QR and median PN of ∆ PQR (see Fig. 7.40).

Fig. 7.40

Show that:

(i) ∆ ABM ≅ ∆ PQN

(ii) ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ PQR

4. BE and CF are two equal altitudes of a triangle ABC. Using RHS congruence rule, prove that the triangle ABC is isosceles.

5. ABC is an isosceles triangle with AB = AC. Draw AP ⊥ BC to show that

∠ B = ∠ C.

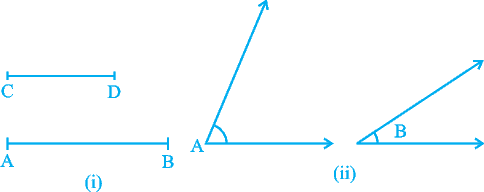

7.6 Inequalities in a Triangle

So far, you have been mainly studying the equality of sides and angles of a triangle or triangles. Sometimes, we do come across unequal objects, we need to compare them. For example, line-segment AB is greater in length as compared to line segment CD in Fig. 7.41 (i) and ∠ A is greater than ∠ B in Fig 7.41 (ii).

Fig. 7.41

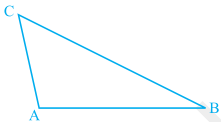

Let us now examine whether there is any relation between unequal sides and unequal angles of a triangle. For this, let us perform the following activity:

Activity : Fix two pins on a drawing board say at B and C and tie a thread to mark a side BC of a triangle.

Fix one end of another thread at C and tie a pencil at the other (free) end . Mark a point A with the pencil and draw ∆ ABC (see Fig 7.42).

Fig. 7.42

Now, shift the pencil and mark another point A′ on CA beyond A (new position of it)

So, A′C > AC (Comparing the lengths)

Join A′ to B and complete the triangle A′BC. What can you say about ∠ A′BC and ∠ ABC?

Compare them. What do you observe?

Clearly, ∠ A′BC > ∠ ABC

Continue to mark more points on CA (extended) and draw the triangles with the side BC and the points marked.

You will observe that as the length of the side AC is increased (by taking different positions of A), the angle opposite to it, that is, ∠ B also increases.

Let us now perform another activity :

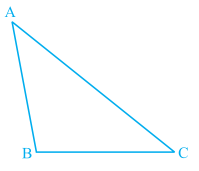

Activity : Construct a scalene triangle (that is a triangle in which all sides are of different lengths). Measure the lengths of the sides.

Now, measure the angles. What do you observe?

In ∆ ABC of Fig 7.43, BC is the longest side and AC is the shortest side.

Fig. 7.43

Also, ∠ A is the largest and ∠ B is the smallest.

Repeat this activity with some other triangles.

We arrive at a very important result of inequalities in a triangle. It is stated in the form of a theorem as shown below:

Theorem 7.6 : If two sides of a triangle are unequal, the angle opposite to the longer side is larger (or greater).

Fig. 7.44

You may prove this theorem by taking a point P on BC such that CA = CP in Fig. 7.43.

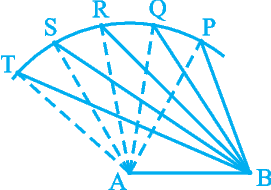

Now, let us perform another activity :

Activity : Draw a line-segment AB. With A as centre and some radius, draw an arc and mark different points say P, Q, R, S, T on it.

Join each of these points with A as well as with B (see Fig. 7.44). Observe that as we move from P to T, ∠ A is becoming larger and larger. What is happening to the length of the side opposite to it? Observe that the length of the side is also increasing; that is

∠ TAB > ∠ SAB > ∠ RAB > ∠ QAB > ∠ PAB and TB > SB > RB > QB > PB.

Now, draw any triangle with all angles unequal to each other. Measure the lengths of the sides

(see Fig. 7.45).

Observe that the side opposite to the largest angle is the longest. In Fig. 7.45,∠ B is the largest angle and AC is the longest side.

Fig. 7.45

Repeat this activity for some more triangles and we see that the converse of Theorem 7.6 is also true. In this way, we arrive at the following theorem:

Theorem 7.7 : In any triangle, the side opposite to the larger (greater) angle is longer.

This theorem can be proved by the method of contradiction.

Now take a triangle ABC and in it, find AB + BC, BC + AC and AC + AB. What do you observe?

You will observe that AB + BC > AC,

BC + AC > AB and AC + AB > BC.

Repeat this activity with other triangles and with this you can arrive at the following theorem :

Theorem 7.8 : The sum of any two sides of a triangle is greater than the third side.

In Fig. 7.46, observe that the side BA of ∆ ABC has been produced to a point D such that AD = AC. Can you show that ∠ BCD > ∠ BDC and BA + AC > BC? Have you arrived at the proof of the above theorem.

Fig. 7.46

Let us now take some examples based on these results.

Example 9 : D is a point on side BC of ∆ ABC such that AD = AC (see Fig. 7.47). Show that AB > AD.

Fig. 7.47

Solution : In ∆ DAC,

AD = AC (Given)

So, ∠ ADC = ∠ ACD

(Angles opposite to equal sides)

Now, ∠ ADC is an exterior angle for ∆ABD.

So, ∠ ADC > ∠ ABD

or, ∠ ACD > ∠ ABD

or, ∠ ACB > ∠ ABC

So, AB > AC (Side opposite to larger angle in ∆ ABC)

or, AB > AD (AD = AC)

Exercise 7.4

1. Show that in a right angled triangle, the hypotenuse is the longest side.

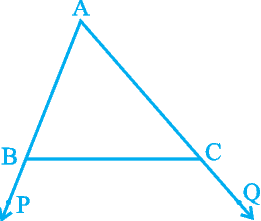

2. In Fig. 7.48, sides AB and AC of ∆ ABC are extended to points P and Q respectively. Also,

∠ PBC < ∠ QCB. Show that AC > AB.

Fig. 7.48

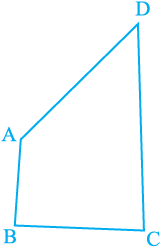

3. In Fig. 7.49, ∠ B < ∠ A and ∠ C < ∠ D. Show that AD < BC.

Fig. 7.49

4. AB and CD are respectively the smallest and longest sides of a quadrilateral ABCD

(see Fig. 7.50). Show that ∠ A > ∠ C and

∠ B > ∠ D.

Fig. 7.50

5. In Fig 7.51, PR > PQ and PS bisects ∠ QPR. Prove that ∠ PSR > ∠ PSQ.

Fig. 7.51

6. Show that of all line segments drawn from a given point not on it, the perpendicular line segment is the shortest.

Exercise 7.5 (Optional)*

1. ABC is a triangle. Locate a point in the interior of ∆ ABC which is equidistant from all the vertices of ∆ ABC.

2. In a triangle locate a point in its interior which is equidistant from all the sides of the triangle.

3. In a huge park, people are concentrated at three points (see Fig. 7.52):

A : where there are different slides and swings for children,

B : near which a man-made lake is situated,

C : which is near to a large parking and exit.

Where should an icecream parlour be set up so that maximum number of persons can approach it?

(Hint : The parlour should be equidistant from A, B and C)

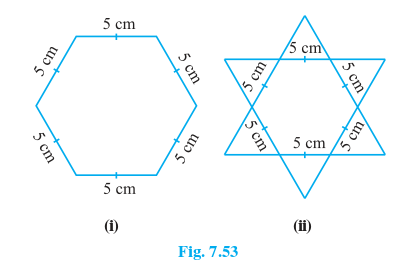

4. Complete the hexagonal and star shaped Rangolies [see Fig. 7.53 (i) and (ii)] by filling them with as many equilateral triangles of side 1 cm as you can. Count the number of triangles in each case. Which has more triangles?

(i) (ii)

*These exercises are not from examination point of view.

7.7 Summary

In this chapter, you have studied the following points :

1. Two figures are congruent, if they are of the same shape and of the same size.

2. Two circles of the same radii are congruent.

3. Two squares of the same sides are congruent.

4. If two triangles ABC and PQR are congruent under the correspondence A ↔ P,

B ↔ Q and C ↔ R, then symbolically, it is expressed as ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ PQR.

5. If two sides and the included angle of one triangle are equal to two sides and the included angle of the other triangle, then the two triangles are congruent (SAS Congruence Rule).

6. If two angles and the included side of one triangle are equal to two angles and the included side of the other triangle, then the two triangles are congruent (ASA Congruence Rule).

7. If two angles and one side of one triangle are equal to two angles and the corresponding side of the other triangle, then the two triangles are congruent (AAS Congruence Rule).

8. Angles opposite to equal sides of a triangle are equal.

9. Sides opposite to equal angles of a triangle are equal.

10. Each angle of an equilateral triangle is of 60°.

11. If three sides of one triangle are equal to three sides of the other triangle, then the two triangles are congruent (SSS Congruence Rule).

12. If in two right triangles, hypotenuse and one side of a triangle are equal to the hypotenuse and one side of other triangle, then the two triangles are congruent (RHS Congruence Rule).

13. In a triangle, angle opposite to the longer side is larger (greater).

14. In a triangle, side opposite to the larger (greater) angle is longer.

15. Sum of any two sides of a triangle is greater than the third side.