Table of Contents

Chapter 10

Circles

10.1 Introduction

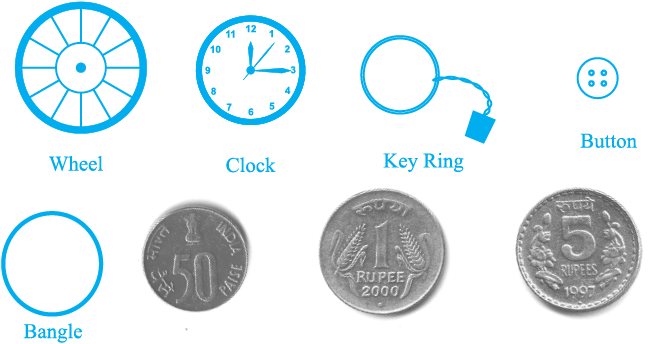

You may have come across many objects in daily life, which are round in shape, such as wheels of a vehicle, bangles, dials of many clocks, coins of denominations 50 p, Re 1 and Rs 5, key rings, buttons of shirts, etc. (see Fig.10.1). In a clock, you might have observed that the second’s hand goes round the dial of the clock rapidly and its tip moves in a round path. This path traced by the tip of the second’s hand is called a circle. In this chapter, you will study about circles, other related terms and some properties of a circle.

Fig. 10.1

10.2 Circles and Its Related Terms: A Review

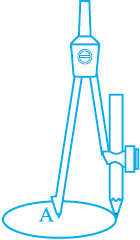

Take a compass and fix a pencil in it. Put its pointed leg on a point on a sheet of a paper. Open the other leg to some distance. Keeping the pointed leg on the same point, rotate the other leg through one revolution. What is the closed figure traced by the pencil on paper?

Fig. 10.2

As you know, it is a circle (see Fig.10.2).How did you get a circle? You kept one point fixed (A in Fig.10.2) and drew all the points that were at a fixed distance from A. This gives us the following definition:

The collection of all the points in a plane, which are at a fixed distance from a fixed point in the plane, is called a circle.

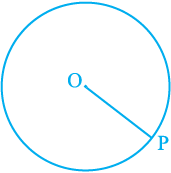

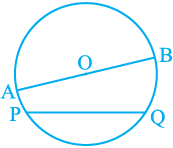

The fixed point is called the centre of the circle and the fixed distance is called the radius of the circle. In Fig.10.3, O is the centre and the length OP is the radius of the circle.

Fig. 10.3

Remark : Note that the line segment joining the centre and any point on the circle is also called a radius of the circle. That is, ‘radius’ is used in two senses-in the sense of a line segment and also in the sense of its length.

You are already familiar with some of the following concepts from Class VI. We are just recalling them.

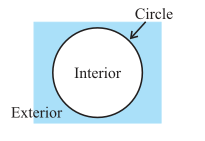

A circle divides the plane on which it lies into three parts. They are: (i) inside the circle, which is also called the interior of the circle; (ii) the circle and (iii) outside the circle, which is also called the exterior of the circle (see Fig.10.4).The circle and its interior make up the circular region.

Fig. 10.4

If you take two points P and Q on a circle, then the line segment PQ is called a chord of the circle (see Fig. 10.5). The chord, which passes through the centre of the circle, is called a diameter of the circle. As in the case of radius, the word ‘diameter’ is also used in two senses, that is, as a line segment and also as its length. Do you find any other chord of the circle longer than a diameter? No, you see that a diameter is the longest chord and all diameters have the same length, which is equal to two times the radius. In Fig.10.5, AOB is a diameter of the circle. How many diameters does a circle have? Draw a circle and see how many diameters you can find.

Fig. 10.5

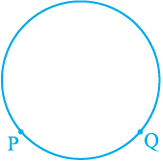

A piece of a circle between two points is called an arc. Look at the pieces of the circle between two points P and Q in Fig.10.6.

Fig. 10.6

You find that there are two pieces, one longer and the other smaller

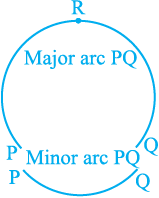

(see Fig.10.7).

Fig. 10.7

The longer one is called the major arc PQ and the shorter one is called the minor arc PQ. The minor arc PQ is also denoted by and the major arc PQ by , where R is some point on the arc between P and Q. Unless otherwise stated, arc PQ or stands for minor arc PQ. When P and Q are ends of a diameter, then both arcs are equal and each is called a semicircle.

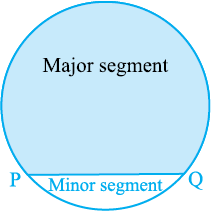

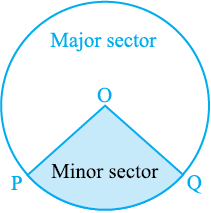

The length of the complete circle is called its circumference. The region between a chord and either of its arcs is called a segment of the circular region or simply a segment of the circle. You will find that there are two types of segments also, which are the major segment and the minor segment (see Fig. 10.8). The region between an arc and the two radii, joining the centre to the end points of the arc is called a sector. Like segments, you find that the minor arc corresponds to the minor sector and the major arc corresponds to the major sector. In Fig. 10.9, the region OPQ is the minor sector and remaining part of the circular region is the major sector. When two arcs are equal, that is, each is a semicircle, then both segments and both sectors become the same and each is known as a semicircular region.

Fig. 10.8

Fig. 10.9

EXERCISE 10.1

1. Fill in the blanks:

(i) The centre of a circle lies in________ of the circle. (exterior/ interior)

(ii) A point, whose distance from the centre of a circle is greater than its radius lies in _______ of the circle. (exterior/ interior)

(iii) The longest chord of a circle is a ___________ of the circle.

(iv) An arc is a ___________ - when its ends are the ends of a diameter.

(v) Segment of a circle is the region between an arc and ___________ of the circle.

(vi) A circle divides the plane, on which it lies, in ___________ parts.

2. Write True or False: Give reasons for your answers.

(i) Line segment joining the centre to any point on the circle is a radius of the circle.

(ii) A circle has only finite number of equal chords.

(iii) If a circle is divided into three equal arcs, each is a major arc.

(iv) A chord of a circle, which is twice as long as its radius, is a diameter of the circle.

(v) Sector is the region between the chord and its corresponding arc.

(vi) A circle is a plane figure.

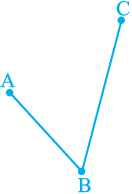

10.3 Angle Subtended by a Chord at a Point

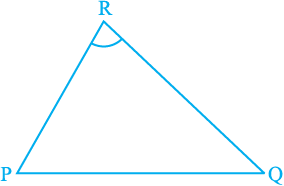

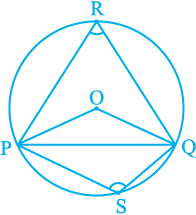

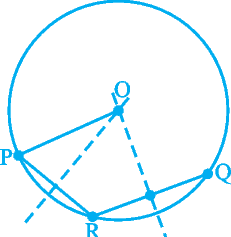

Take a line segment PQ and a point R not on the line containing PQ. Join PR and QR (see Fig. 10.10). Then ∠ PRQ is called the angle subtended by the line segment PQ at the point R. What are angles POQ, PRQ and PSQ called in Fig. 10.11? ∠ POQ is the angle subtended by the chord PQ at the centre O, ∠ PRQ and ∠ PSQ are respectively the angles subtended by PQ at points R and S on the major and minor arcs PQ.

Fig. 10.10

Fig. 10.11

Let us examine the relationship between the size of the chord and the angle subtended by it at the centre. You may see by drawing different chords of a circle and

angles subtended by them at the centre that the longer is the chord, the bigger will be the angle subtended by it at the centre. What will happen if you take two equal chords of a circle? Will the angles subtended at the centre be the same or not?

Draw two or more equal chords of a circle and measure the angles subtended by them at the centre (see Fig.10.12).

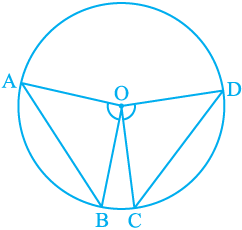

Fig.10.12

You will find that the angles subtended by them at the centre are equal. Let us give a proof of this fact.

Theorem 10.1 : Equal chords of a circle subtend equal angles at the centre.

Proof : You are given two equal chords AB and CD of a circle with centre O (see Fig.10.13).

Fig. 10.13

You want to prove that ∠ AOB = ∠ COD.

In triangles AOB and COD,

OA = OC (Radii of a circle)

OB = OD (Radii of a circle)

AB = CD (Given)

Therefore, ∆ AOB ≅ ∆COD (SSS rule)

This gives ∠ AOB = ∠ COD

(Corresponding parts of congruent triangles)

Remark : For convenience, the abbreviation CPCT will be used in place of ‘Corresponding parts of congruent triangles’, because we use this very frequently as you will see.

Now if two chords of a circle subtend equal angles at the centre, what can you say about the chords? Are they equal or not? Let us examine this by the following activity:

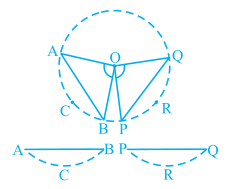

Take a tracing paper and trace a circle on it. Cut it along the circle to get a disc. At its centre O, draw an angle AOB where A, B are points on the circle. Make another angle POQ at the centre equal to ∠ AOB. Cut the disc along AB and PQ (see Fig. 10.14).

Fig. 10.14

You will get two segments ACB and PRQ of the circle. If you put one on the other, what do you observe? They cover each other, i.e., they are congruent. So AB = PQ.

Though you have seen it for this particular case, try it out for other equal angles too. The chords will all turn out to be equal because of the following theorem:

Theorem 10.2 : If the angles subtended by the chords of a circle at the centre are equal, then the chords are equal.

The above theorem is the converse of the Theorem 10.1. Note that in Fig. 10.13, if you take ∠ AOB = ∠ COD, then

∆ AOB ≅ ∆COD (Why?)

Can you now see that AB = CD?

EXERCISE 10.2

1. Recall that two circles are congruent if they have the same radii. Prove that equal chords of congruent circles subtend equal angles at their centres.

2. Prove that if chords of congruent circles subtend equal angles at their centres, then the chords are equal.

10.4 Perpendicular from the Centre to a Chord

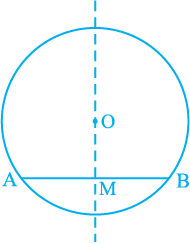

Activity : Draw a circle on a tracing paper. Let O be its centre. Draw a chord AB. Fold the paper along a line through O so that a portion of the chord falls on the other. Let the crease cut AB at the point M. Then, ∠ OMA = ∠ OMB = 90° or OM is perpendicular to AB. Does the point B coincide with A (see Fig.10.15)?

Yes it will. So MA = MB.

Fig. 10.15

Give a proof yourself by joining OA and OB and proving the right triangles OMA and OMB to be congruent. This example is a particular instance of the following result:

Theorem 10.3 : The perpendicular from the centre of a circle to a chord bisects the chord.

What is the converse of this theorem? To write this, first let us be clear what is assumed in Theorem 10.3 and what is proved. Given that the perpendicular from the centre of a circle to a chord is drawn and to prove that it bisects the chord. Thus in the converse, what the hypothesis is ‘if a line from the centre bisects a chord of a circle’ and what is to be proved is ‘the line is perpendicular to the chord’. So the converse is:

Theorem 10.4 : The line drawn through the centre of a circle to bisect a chord is perpendicular to the chord.

Is this true? Try it for few cases and see. You will see that it is true for these cases. See if it is true, in general, by doing the following exercise. We will write the stages and you give the reasons.

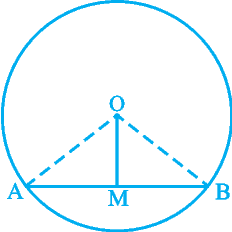

Let AB be a chord of a circle with centre O and O is joined to the mid-point M of AB. You have to prove that OM ⊥ AB. Join OA and OB

(see Fig. 10.16). In triangles OAM and OBM,

Fig. 10.16

OA = OB (Why ?)

AM = BM (Why ?)

OM = OM (Common)

Therefore, ∆OAM ≅ ∆OBM (How ?)

This gives ∠ OMA = ∠ OMB = 90° (Why ?)

10.5 Circle through Three Points

You have learnt in Chapter 6, that two points are sufficient to determine a line. That is, there is one and only one line passing through two points. A natural question arises. How many points are sufficient to determine a circle?

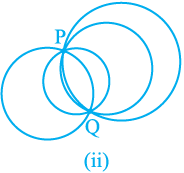

Take a point P. How many circles can be drawn through this point? You see that there may be as many circles as you like passing through this point [see Fig. 10.17(i)]. Now take two points P and Q. You again see that there may be an infinite number of circles passing through P and Q [see Fig.10.17(ii)]. What will happen when you take three points A, B and C? Can you draw a circle passing through three collinear points?

Fig. 10. 17

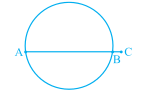

No. If the points lie on a line, then the third point will lie inside or outside the circle passing through two points (see Fig 10.18).

Fig. 10.18

So, let us take three points A, B and C, which are not on the same line, or in other words, they are not collinear [see Fig. 10.19(i)]. Draw perpendicular bisectors of AB and BC say, PQ and RS respectively. Let these perpendicular bisectors intersect at one point O. (Note that PQ and RS will intersect because they are not parallel) [see Fig. 10.19(ii)].

Fig. 10.19

Now O lies on the perpendicular bisector PQ of AB, you have OA = OB, as every point on the perpendicular bisector of a line segment is equidistant from its end points, proved in Chapter 7.

Similarly, as O lies on the perpendicular bisector RS of BC, you get

OB = OC

So OA = OB = OC, which means that the points A, B and C are at equal distances from the point O. So if you draw a circle with centre O and radius OA, it will also pass through B and C. This shows that there is a circle passing through the three points A, B and C. You know that two lines (perpendicular bisectors) can intersect at only one point, so you can draw only one circle with radius OA. In other words, there is a unique circle passing through A, B and C. You have now proved the following theorem:

Theorem 10.5 : There is one and only one circle passing through three given non-collinear points.

Remark : If ABC is a triangle, then by Theorem 10.5, there is a unique circle passing through the three vertices A, B and C of the triangle. This circle is called the circumcircle of the ∆ ABC. Its centre and radius are called respectively the circumcentre and the circumradius of the triangle.

Example 1 : Given an arc of a circle, complete the circle.

Solution : Let arc PQ of a circle be given. We have to complete the circle, which means that we have to find its centre and radius. Take a point R on the arc. Join PR and RQ. Use the construction that has been used in proving Theorem 10.5, to find the centre and radius.

Taking the centre and the radius so obtained, we can complete the circle (see Fig. 10.20).

Fig. 10.20

EXERCISE 10.3

1. Draw different pairs of circles. How many points does each pair have in common? What is the maximum number of common points?

2. Suppose you are given a circle. Give a construction to find its centre.

3. If two circles intersect at two points, prove that their centres lie on the perpendicular bisector of the common chord.

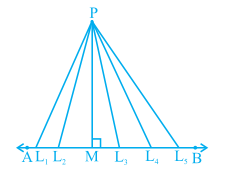

10.6 Equal Chords and Their Distances from the Centre

Let AB be a line and P be a point. Since there are infinite numbers of points on a line, if you join these points to P, you will get infinitely many line segments PL1, PL2, PM, PL3, PL4, etc. Which of these is the distance of AB from P? You may think a while and get the answer. Out of these line segments, the perpendicular from P to AB, namely PM in Fig. 10.21, will be the least. In Mathematics, we define this least length PM to be the distance of AB from P. So you may say that:

Fig. 10.21

The length of the perpendicular from a point to a line is the distance of the line from the point.

Note that if the point lies on the line, the distance of the line from the point is zero.

A circle can have infinitely many chords. You may observe by drawing chords of a circle that longer chord is nearer to the centre than the smaller chord. You may observe it by drawing several chords of a circle of different lengths and measuring their distances from the centre. What is the distance of the diameter, which is the longest chord from the centre? Since the centre lies on it, the distance is zero. Do you think that there is some relationship between the length of chords and their distances from the centre? Let us see if this is so.

Fig. 10.22

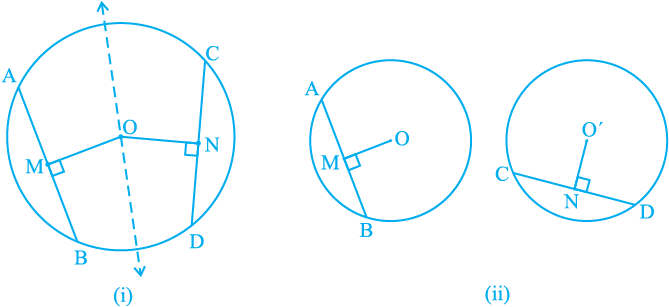

Activity : Draw a circle of any radius on a tracing paper. Draw two equal chords AB and CD of it and also the perpendiculars OM and ON on them from the centre O. Fold the figure so that D falls on B and C falls on A [see Fig.10.22 (i)]. You may observe that O lies on the crease and N falls on M. Therefore, OM = ON. Repeat the activity by drawing congruent circles with centres O and O′ and taking equal chords AB and CD one on each. Draw perpendiculars OM and O′N on them [see Fig. 10.22(ii)].Cut one circular disc and put it on the other so that AB coincides with CD. Then you will find that O coincides with O′ and M coincides with N. In this way you verified the following:

Theorem 10.6 : Equal chords of a circle (or of congruent circles) are equidistant from the centre (or centres).

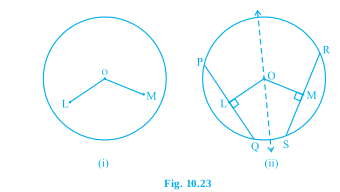

Next, it will be seen whether the converse of this theorem is true or not. For this, draw a circle with centre O. From the centre O, draw two line segments OL and OM of equal length and lying inside the circle [see Fig. 10.23(i)]. Then draw chords PQ and RS of the circle perpendicular to OL and OM respectively [see Fig 10.23(ii)]. Measure the lengths of PQ and RS. Are these different? No, both are equal. Repeat the activity for more equal line segments and drawing the chords perpendicular to them. This verifies the converse of the Theorem 10.6 which is stated as follows:

Theorem 10.7 : Chords equidistant from the centre of a circle are equal in length.

We now take an example to illustrate the use of the above results:

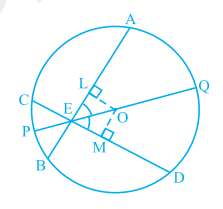

Example 2 : If two intersecting chords of a circle make equal angles with the diameter passing through their point of intersection, prove that the chords are equal.

Solution : Given that AB and CD are two chords of a circle, with centre O intersecting at a point E. PQ is a diameter through E, such that ∠ AEQ = ∠ DEQ (see Fig.10.24). You have to prove that AB = CD. Draw perpendiculars OL and OM on chords AB and

Fig. 10.24

CD, respectively. Now

∠ LOE = 180° – 90° – ∠ LEO = 90° – ∠ LEO

(Angle sum property of a triangle)

= 90° – ∠ AEQ = 90° – ∠ DEQ

= 90° – ∠ MEO = ∠ MOE

In triangles OLE and OME,

∠ LEO = ∠ MEO (Why ?)

∠ LOE = ∠ MOE (Proved above)

EO = EO (Common)

Therefore, ∆OLE ≅ ∆OME (Why ?)

This gives OL = OM (CPCT)

So, AB = CD (Why ?)

EXERCISE 10.4

1. Two circles of radii 5 cm and 3 cm intersect at two points and the distance between their centres is 4 cm. Find the length of the common chord.

2. If two equal chords of a circle intersect within the circle, prove that the segments of one chord are equal to corresponding segments of the other chord.

3. If two equal chords of a circle intersect within the circle, prove that the line joining the point of intersection to the centre makes equal angles with the chords.

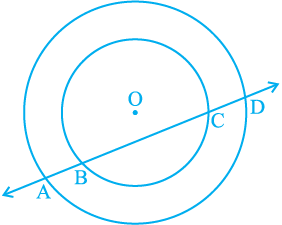

4. If a line intersects two concentric circles (circles with the same centre) with centre O at A, B, C and D, prove that AB = CD (see Fig. 10.25).

Fig. 10.25

5. Three girls Reshma, Salma and Mandip are playing a game by standing on a circle of radius 5m drawn in a park. Reshma throws a ball to Salma, Salma to Mandip, Mandip to Reshma. If the distance between Reshma and Salma and between Salma and Mandip is 6m each, what is the distance between Reshma and Mandip?

6. A circular park of radius 20m is situated in a colony. Three boys Ankur, Syed and David are sitting at equal distance on its boundary each having a toy telephone in his hands to talk each other. Find the length of the string of each phone.

10.7 Angle Subtended by an Arc of a Circle

You have seen that the end points of a chord other than diameter of a circle cuts it into two arcs – one major and other minor. If you take two equal chords, what can you say about the size of arcs? Is one arc made by first chord equal to the corresponding arc made by another chord? In fact, they are more than just equal in length. They are congruent in the sense that if one arc is put on the other, without bending or twisting, one superimposes the other completely.

You can verify this fact by cutting the arc, corresponding to the chord CD from the circle along CD and put it on the corresponding arc made by equal chord AB. You will find that the arc CD superimpose the arc AB completely (see Fig. 10.26).

Fig. 10.26

This shows that equal chords make congruent arcs and conversely congruent arcs make equal chords of a circle. You can state it as follows:

If two chords of a circle are equal, then their corresponding arcs are congruent and conversely, if two arcs are congruent, then their corresponding chords are equal.

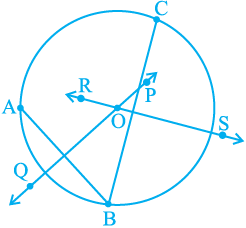

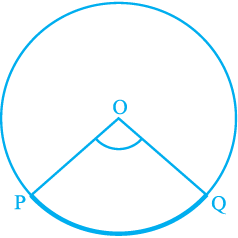

Also the angle subtended by an arc at the centre is defined to be angle subtended by the corresponding chord at the centre in the sense that the minor arc subtends the angle and the major arc subtends the reflex angle. Therefore, in Fig 10.27, the angle subtended by the minor arc PQ at O is ∠ POQ and the angle subtended by the major arc PQ at O is reflex angle POQ.

Fig. 10.27

In view of the property above and Theorem 10.1, the following result is true:

Congruent arcs (or equal arcs) of a circle subtend equal angles at the centre.

Therefore, the angle subtended by a chord of a circle at its centre is equal to the angle subtended by the corresponding (minor) arc at the centre. The following theorem gives the relationship between the angles subtended by an arc at the centre and at a point on the circle.

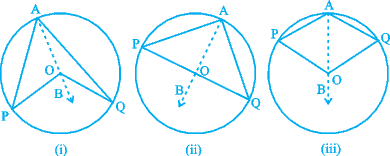

Proof : Given an arc PQ of a circle subtending angles POQ at the centre O and PAQ at a point A on the remaining part of the circle. We need to prove that

∠ POQ = 2 ∠ PAQ.

Fig. 10.28

Consider the three different cases as given in Fig. 10.28. In (i), arc PQ is minor; in (ii), arc PQ is a semicircle and in (iii), arc PQ is major.

Let us begin by joining AO and extending it to a point B.

In all the cases,

∠ BOQ = ∠ OAQ + ∠ AQO

because an exterior angle of a triangle is equal to the sum of the two interior opposite angles.

Also in ∆ OAQ,

OA = OQ (Radii of a circle)

Therefore, ∠ OAQ = ∠ OQA (Theorem 7.5)

This gives ∠ BOQ = 2 ∠ OAQ (1)

Similarly, ∠ BOP = 2 ∠ OAP (2)

From (1) and (2), ∠ BOP + ∠ BOQ = 2(∠ OAP + ∠ OAQ)

This is the same as ∠ POQ = 2 ∠ PAQ (3)

For the case (iii), where PQ is the major arc, (3) is replaced by

reflex angle POQ = 2 ∠ PAQ

Remark : Suppose we join points P and Q and form a chord PQ in the above figures. Then

∠ PAQ is also called the angle formed in the segment PAQP.

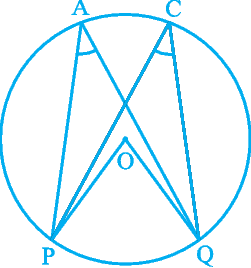

In Theorem 10.8, A can be any point on the remaining part of the circle. So if you take any other point C on the remaining part of the circle (see Fig. 10.29), you have

Fig. 10.29

∠ POQ = 2 ∠ PCQ = 2 ∠ PAQ

Therefore, ∠ PCQ = ∠ PAQ.

This proves the following:

Theorem 10.9 : Angles in the same segment of a circle are equal.

Again let us discuss the case (ii) of Theorem 10.8 separately. Here ∠ PAQ is an angle in the segment, which is a semicircle. Also, ∠ PAQ = ∠ POQ = × 180° = 90°. If you take any other point C on the semicircle, again you get that

∠ PCQ = 90°

Therefore, you find another property of the circle as:

Angle in a semicircle is a right angle.

The converse of Theorem 10.9 is also true. It can be stated as:

Theorem 10.10 : If a line segment joining two points subtends equal angles at two other points lying on the same side of the line containing the line segment, the four points lie on a circle (i.e. they are concyclic).

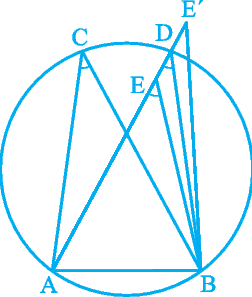

You can see the truth of this result as follows:

In Fig. 10.30, AB is a line segment, which subtends equal angles at two points C and D. That is

∠ ACB = ∠ ADB

To show that the points A, B, C and D lie on a circle let us draw a circle through the points A, C and B. Suppose it does not pass through the point D. Then it will intersect AD (or extended AD) at a point, say E (or E′).

If points A, C, E and B lie on a circle,

∠ ACB = ∠ AEB (Why?)

But it is given that ∠ ACB = ∠ ADB.

Therefore, ∠ AEB = ∠ ADB.

This is not possible unless E coincides with D. (Why?)

Similarly, E′ should also coincide with D.

Fig. 10.30

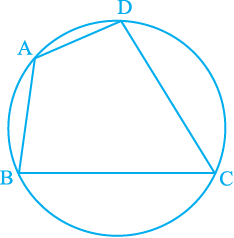

10.8 Cyclic Quadrilaterals

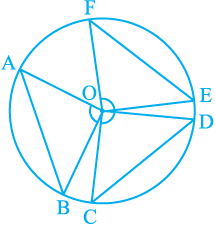

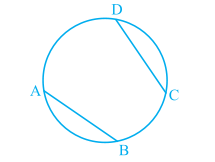

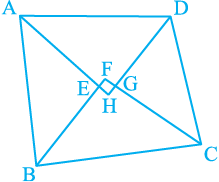

A quadrilateral ABCD is called cyclic if all the four vertices of it lie on a circle (see Fig 10.31).

Fig. 10.31

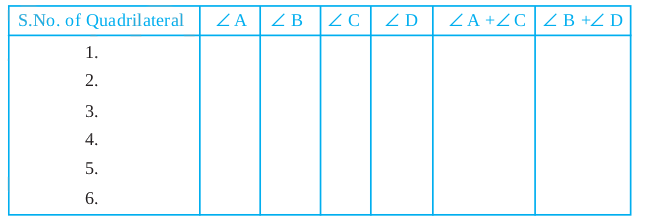

You will find a peculiar property in such quadrilaterals. Draw several cyclic quadrilaterals of different sides and name each of these as ABCD. (This can be done by drawing several circles of different radii and taking four points on each of them.) Measure the opposite angles and write your observations in the following table.

What do you infer from the table?

You find that ∠ A + ∠ C = 180° and ∠ B + ∠ D = 180°, neglecting the error in measurements. This verifies the following:

Theorem 10.11 : The sum of either pair of opposite angles of a cyclic quadrilateral is 180°

In fact, the converse of this theorem, which is stated below is also true.

Theorem 10.12 : If the sum of a pair of opposite angles of a quadrilateral is 180°, the quadrilateral is cyclic.

You can see the truth of this theorem by following a method similar to the method adopted for Theorem 10.10.

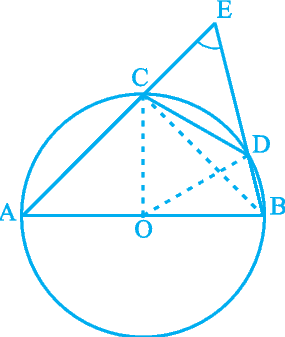

Example 3 : In Fig. 10.32, AB is a diameter of the circle, CD is a chord equal to the radius of the circle. AC and BD when extended intersect at a point E. Prove that

∠ AEB = 60°.

Fig. 10.32

Solution : Join OC, OD and BC.

Triangle ODC is equilateral (Why?)

Therefore, ∠ COD = 60°

Now, ∠ CBD = ∠ COD (Theorem 10.8)

This gives ∠ CBD = 30°

Again, ∠ ACB = 90° (Why ?)

So, ∠ BCE = 180° – ∠ ACB = 90°

Which gives ∠ CEB = 90° – 30° = 60°, i.e., ∠ AEB = 60°

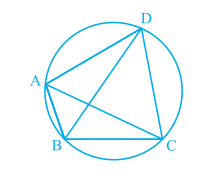

Example 4 : In Fig 10.33, ABCD is a cyclic quadrilateral in which AC and BD are its diagonals. If ∠ DBC = 55° and ∠ BAC = 45°, find ∠ BCD.

Fig. 10.33

Solution : ∠ CAD = ∠ DBC = 55°

(Angles in the same segment)

Therefore, ∠ DAB = ∠ CAD + ∠ BAC

= 55° + 45° = 100°

But ∠ DAB + ∠ BCD = 180°

(Opposite angles of a cyclic quadrilateral)

So, ∠ BCD = 180° – 100° = 80°

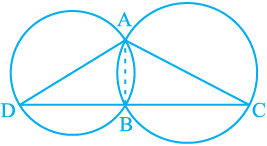

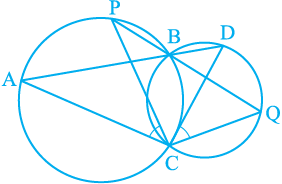

Example 5 : Two circles intersect at two points A and B. AD and AC are diameters to the two circles (see Fig.10.34).

Fig. 10.34

Prove that B lies on the line segment DC.

Solution : Join AB.

∠ ABD = 90° (Angle in a semicircle)

∠ ABC = 90° (Angle in a semicircle)

So, ∠ ABD + ∠ ABC = 90° + 90° = 180°

Therefore, DBC is a line. That is B lies on the line segment DC.

Example 6 : Prove that the quadrilateral formed (if possible) by the internal angle bisectors of any quadrilateral is cyclic.

Fig. 10.35

Solution : In Fig. 10.35, ABCD is a quadrilateral in which the angle bisectors AH, BF, CF and DH of internal angles A, B, C and D respectively form a quadrilateral EFGH.

Now, ∠ FEH = ∠ AEB = 180° – ∠ EAB – ∠ EBA (Why ?)

= 180° – (∠ A + ∠ B)

and ∠ FGH = ∠ CGD = 180° – ∠ GCD – ∠ GDC (Why ?)

= 180° – (∠ C + ∠ D)

Therefore, ∠ FEH + ∠ FGH = 180° – (∠ A + ∠ B) + 180° – (∠ C + ∠ D)

= 360° – (∠ A+ ∠ B +∠ C +∠ D) = 360° – × 360°

= 360° – 180° = 180°

Therefore, by Theorem 10.12, the quadrilateral EFGH is cyclic.

EXERCISE 10.5

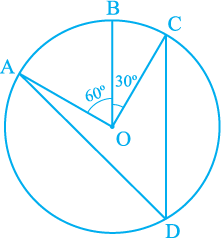

1. In Fig. 10.36, A,B and C are three points on a circle with centre O such that ∠ BOC = 30° and

∠ AOB = 60°. If D is a point on the circle other than the arc ABC, find ∠ ADC.

Fig. 10.36

2. A chord of a circle is equal to the radius of the circle. Find the angle subtended by the chord at a point on the minor arc and also at a point on the major arc.

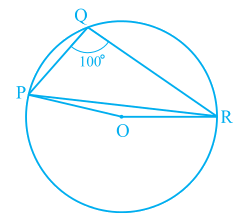

3. In Fig. 10.37, ∠ PQR = 100°, where P, Q and R are points on a circle with centre O. Find ∠ OPR.

Fig. 10.37

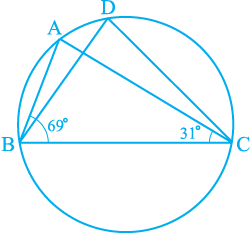

4. In Fig. 10.38, ∠ ABC = 69°, ∠ ACB = 31°, find ∠ BDC.

Fig. 10.38

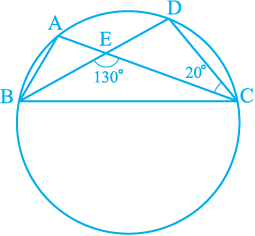

5. In Fig. 10.39, A, B, C and D are four points on a circle. AC and BD intersect at a point E such that ∠ BEC = 130° and ∠ ECD = 20°. Find

∠ BAC.

Fig. 10.39

6. ABCD is a cyclic quadrilateral whose diagonals intersect at a point E. If ∠ DBC = 70°, ∠ BAC is 30°, find ∠ BCD. Further, if AB = BC, find ∠ ECD.

7. If diagonals of a cyclic quadrilateral are diameters of the circle through the vertices of the quadrilateral, prove that it is a rectangle.

8. If the non-parallel sides of a trapezium are equal, prove that it is cyclic.

9. Two circles intersect at two points B and C. Through B, two line segments ABD and PBQ are drawn to intersect the circles at A, D and P, Q respectively (see Fig. 10.40). Prove that

∠ ACP = ∠ QCD.

Fig. 10.40

10. If circles are drawn taking two sides of a triangle as diameters, prove that the point of intersection of these circles lie on the third side.

11. ABC and ADC are two right triangles with common hypotenuse AC. Prove that

∠ CAD = ∠ CBD.

12. Prove that a cyclic parallelogram is a rectangle.

Exercise 10.6 (Optional)*

1. Prove that the line of centres of two intersecting circles subtends equal angles at the two points of intersection.

2. Two chords AB and CD of lengths 5 cm and 11 cm respectively of a circle are parallel to each other and are on opposite sides of its centre. If the distance between AB and CD is 6 cm, find the radius of the circle.

3. The lengths of two parallel chords of a circle are 6 cm and 8 cm. If the smaller chord is at distance 4 cm from the centre, what is the distance of the other chord from the centre?

4. Let the vertex of an angle ABC be located outside a circle and let the sides of the angle intersect equal chords AD and CE with the circle. Prove that ∠ ABC is equal to half the difference of the angles subtended by the chords AC and DE at the centre.

5. Prove that the circle drawn with any side of a rhombus as diameter, passes through the point of intersection of its diagonals.

6. ABCD is a parallelogram. The circle through A, B and C intersect CD (produced if necessary) at E. Prove that AE = AD.

7. AC and BD are chords of a circle which bisect each other. Prove that (i) AC and BD are diameters, (ii) ABCD is a rectangle.

8. Bisectors of angles A, B and C of a triangle ABC intersect its circumcircle at D, E and F respectively. Prove that the angles of the triangle DEF are 90° –A, 90°

–A, 90° – B and 90°

– B and 90°  – C.

– C.

9. Two congruent circles intersect each other at points A and B. Through A any line segment PAQ is drawn so that P, Q lie on the two circles. Prove that BP = BQ.

10. In any triangle ABC, if the angle bisector of ∠ A and perpendicular bisector of BC intersect, prove that they intersect on the circumcircle of the triangle ABC.

*These exercises are not from examination point of view.

10.9 Summary

In this chapter, you have studied the following points:

1. A circle is the collection of all points in a plane, which are equidistant from a fixed point in the plane.

2. Equal chords of a circle (or of congruent circles) subtend equal angles at the centre.

3. If the angles subtended by two chords of a circle (or of congruent circles) at the centre (corresponding centres) are equal, the chords are equal.

4. The perpendicular from the centre of a circle to a chord bisects the chord.

5. The line drawn through the centre of a circle to bisect a chord is perpendicular to the chord.

6. There is one and only one circle passing through three non-collinear points.

7. Equal chords of a circle (or of congruent circles) are equidistant from the centre (or corresponding centres).

8. Chords equidistant from the centre (or corresponding centres) of a circle (or of congruent circles) are equal.

9. If two arcs of a circle are congruent, then their corresponding chords are equal and conversely if two chords of a circle are equal, then their corresponding arcs (minor, major) are congruent.

10. Congruent arcs of a circle subtend equal angles at the centre.

11. The angle subtended by an arc at the centre is double the angle subtended by it at any point on the remaining part of the circle.

12. Angles in the same segment of a circle are equal.

13. Angle in a semicircle is a right angle.

14. If a line segment joining two points subtends equal angles at two other points lying on the same side of the line containing the line segment, the four points lie on a circle.

15. The sum of either pair of opposite angles of a cyclic quadrilateral is 1800.

16. If sum of a pair of opposite angles of a quadrilateral is 1800, the quadrilateral is cyclic.