Table of Contents

Before You Read

They say faith can move mountains. But what should we put our faith in? This is the question this story delicately poses.

Lencho is a farmer who writes a letter to God when his crops are ruined, asking for a hundred pesos. Does Lencho’s letter reach God? Does God send him the money? Think what your answers to these questions would be, and guess how the story continues, before you begin to read it.

Activity

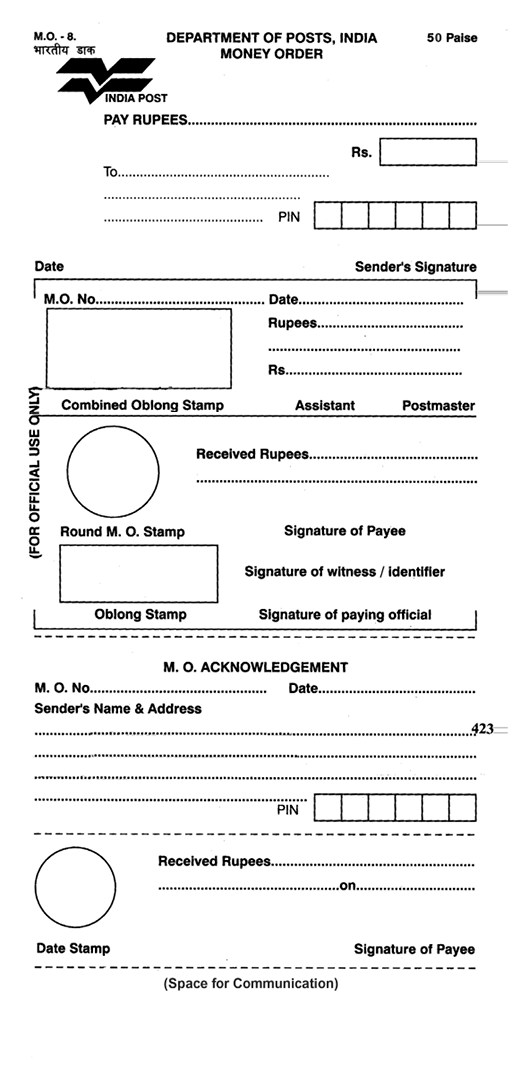

1. One of the cheapest ways to send money to someone is through the post office. Have you ever sent or received money in this way? Here’s what you have to do. (As you read the instructions, discuss with your teacher in class the meanings of these words: counter, counter clerk, appropriate, acknowledgement, counterfoil, record. Consult a dictionary if necessary. Are there words corresponding to these English words in your languages?)

2. Fill out the Money Order form given below using the clues that follow the form.

• Think about who you will send the money to, and how much. You might want to send money for a magazine subscription, or to a relative or a friend.

• Think about who you will send the money to, and how much. You might want to send money for a magazine subscription, or to a relative or a friend.

• Or you may fill out the form with yourself as sender and your partner as receiver. Use a part of your pocket money, and submit the form at the nearest post office to see how it’s done. See how your partner enjoys getting money by post!

• Notice that the form has three parts — the Money Order form, the part for official use and the Acknowledgement. What would you write in the ‘Space for Communication’?

Now complete the following statements.

(i) In addition to the sender, the form has to be signed by the___________________________-.

(ii) The ‘Acknowledgement’ section of the form is sent back by the post office to the ____________

after the _______________ signs it.

(iii) The ‘Space for Communication’ section is used for ___________________.

(iv) The form has six sections. The sender needs to fill

out _________________sections and the receiver____________________________.

The house — the only one in the entire valley — sat on the crest of a low hill. From this height one could see the river and the field of ripe corn dotted with the flowers that always promised a good harvest. The only thing the earth needed was a downpour or at least a shower. Throughout the morning Lencho — who knew his fields intimately — had done nothing else but see the sky towards the north-east.

crest top of a hil

“Now we’re really going to get some water, woman.”

The woman who was preparing supper, replied, “Yes, God willing”. The older boys were working in the field, while the smaller ones were playing near the house until the woman called to them all, “Come for dinner”. It was during the meal that, just as Lencho had predicted, big drops of rain began to fall. In the north-east huge mountains of clouds could be seen approaching. The air was fresh and sweet. The man went out for no other reason than to have the pleasure of feeling the rain on his body, and when he returned he exclaimed, ‘‘These aren’t raindrops falling from the sky, they are new coins. The big drops are ten cent pieces and the little ones are fives.’’

With a satisfied expression he regarded the field of ripe corn with its flowers, draped in a curtain of rain. But suddenly a strong wind began to blow and along with the rain very large hailstones began to fall. These truly did resemble new silver coins. The boys, exposing themselves to the rain, ran out to collect the frozen pearls.

draped covered (with cloth)

‘‘It’s really getting bad now,’’ exclaimed the man. “I hope it passes quickly.” It did not pass quickly. For an hour the hail rained on the house, the garden, the hillside, the cornfield, on the whole valley. The field was white, as if covered with salt.

Not a leaf remained on the trees. The corn was totally destroyed. The flowers were gone from the plants. Lencho’s soul was filled with sadness. When the storm had passed, he stood in the middle of the field and said to his sons, “A plague of locusts would have left more than this. The hail has left nothing. This year we will have no corn.’’

That night was a sorrowful one.

“All our work, for nothing.”

‘‘There’s no one who can help us.”

“We’ll all go hungry this year.”

locusts insects which fly in big swarms (groups) and destroy crops

Oral Comprehension Check

1. What did Lencho hope for?

2. Why did Lencho say the raindrops were like ‘new coins’?

3. How did the rain change? What happened to Lencho’s fields?

4. What were Lencho’s feelings when the hail stopped?

But in the hearts of all who lived in that solitary house in the middle of the valley, there was a single hope: help from God.

“Don’t be so upset, even though this seems like a total loss. Remember, no one dies of hunger.”

“That’s what they say: no one dies of hunger.”

All through the night, Lencho thought only of his one hope: the help of God, whose eyes, as he had been instructed, see everything, even what is deep in one’s conscience. Lencho was an ox of a man, working like an animal in the fields, but still he knew how to write. The following Sunday, at daybreak, he began to write a letter which he himself would carry to town and place in the mail. It was nothing less than a letter to God.

conscience an inner sense of right and wrong

“God,” he wrote, “if you don’t help me, my family and I will go hungry this year. I need a hundred pesos in order to sow my field again and to live until the crop comes, because the hailstorm....”

He wrote ‘To God’ on the envelope, put the letter inside and, still troubled, went to town. At the post office, he placed a stamp on the letter and dropped it into the mailbox.

peso currency of several Latin American countries

One of the employees, who was a postman and also helped at the post office, went to his boss laughing heartily and showed him the letter to God. Never in his career as a postman had he known that address. The postmaster — a fat, amiable fellow — also broke out laughing, but almost immediately he turned serious and, tapping the letter on his desk, commented, “What faith! I wish I had the faith of the man who wrote this letter. Starting up a correspondence with God!”

amiable friendly and pleasant

So, in order not to shake the writer’s faith in God, the postmaster came up with an idea: answer the letter. But when he opened it, it was evident that to answer it he needed something more than goodwill, ink and paper. But he stuck to his resolution: he asked for money from his employees, he himself gave part of his salary, and several friends of his were obliged to give something ‘for an act of charity’.

It was impossible for him to gather together the hundred pesos, so he was able to send the farmer only a little more than half. He put the money in an envelope addressed to Lencho and with it a letter containing only a single word as a signature: God.

Oral Comprehension Check

1. Who or what did Lencho have faith in? What did he do?

2. Who read the letter?

3. What did the postmaster do then?

The following Sunday Lencho came a bit earlier than usual to ask if there was a letter for him.

It was the postman himself who handed the letter to him while the postmaster, experiencing the contentment of a man who has performed a good deed, looked on from his office. contentment satisfaction

Lencho showed not the slightest surprise on seeing the money; such was his confidence — but he became angry when he counted the money. God could not have made a mistake, nor could he have denied Lencho what he had requested.

Immediately, Lencho went up to the window to ask for paper and ink. On the public writing-table, he started to write, with much wrinkling of his brow, caused by the effort he had to make to express his ideas. When he finished, he went to the window to buy a stamp which he licked and then affixed to the envelope with a blow of his fist. The moment the letter fell into the mailbox the postmaster went to open it. It said: “God: Of the money that I asked for, only seventy pesos reached me. Send me the rest, since I need it very much. But don’t send it to me through the mail because the post office employees are a bunch of crooks. Lencho.”

Oral Comprehension Check

1. Was Lencho surprised to find a letter for him with money in it?

2. What made him angry?

2. Why does the postmaster send money to Lencho? Why does he sign the letter ‘God’?

3. Did Lencho try to find out who had sent the money to him? Why/Why not?

4. Who does Lencho think has taken the rest of the money? What is the irony in the situation? (Remember that the irony of a situation is an unexpected aspect of it. An ironic situation is strange or amusing because it is the opposite of what is expected.)

5. Are there people like Lencho in the real world? What kind of a person would you say he is? You may select appropriate words from the box to answer the question.

greedy naive stupid ungrateful

selfish comical unquestioning

6. There are two kinds of conflict in the story: between humans and nature, and between humans themselves. How are these conflicts illustrated?

Thinking about Language

I. Look at the following sentence from the story.

Suddenly a strong wind began to blow and along with the rain very large hailstones began to fall.

‘Hailstones’ are small balls of ice that fall like rain. A storm in which hailstones fall is a ‘hailstorm’. You know that a storm is bad weather with strong winds, rain, thunder and lightning.

There are different names in different parts of the world for storms, depending on their nature. Can you match the names in the box with their descriptions below, and fill in the blanks? You may use a dictionary to help you.

gale, whirlwind, cyclone,

hurricane, tornado, typhoon

1. A violent tropical storm in which strong winds move in a circle:

__ __ c __ __ __ __

2. An extremely strong wind : __ a __ __

3. A violent tropical storm with very strong winds : __ __ p __ __ __ __

4. A violent storm whose centre is a cloud in the shape of a funnel:

__ __ __ n __ __ __

5. A violent storm with very strong winds, especially in the western Atlantic Ocean: __ __ r __ __ __ __ __ __

6. A very strong wind that moves very fast in a spinning movement and causes a lot of damage: __ __ __ __ l __ __ __ __

II. Notice how the word ‘hope’ is used in these sentences from the story:

(a) I hope it (the hailstorm) passes quickly.

(b) There was a single hope: help from God.

In the first example, ‘hope’ is a verb which means you wish for something to happen. In the second example it is a noun meaning a chance for something to happen.

Match the sentences in Column A with the meanings of ‘hope’ in Column B.

| No. | A | B |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Will you get the subjects you want to study in college? I hope so. | – a feeling that something good will probably happen |

| 2. | I hope you don’t mind my saying this, but I don’t like the way you are arguing. | – thinking that this would happen (It may or may not have happened.) |

| 3. | This discovery will give new hope to HIV/AIDS sufferers. | – wanting something to happen (and thinking it quite possible) |

| 4. | We were hoping against hope that the judges would not notice our mistakes. | – showing concern that what you say should not offend or disturb the other person: a way of being polite |

| 5. | I called early in the hope of speaking to her before she went to school. | – showing concern that what you say should not offend or disturb the other person: a way of being polite |

| 6. | Just when everybody had given up hope, the fishermen came back, seven days after the cyclone. | – wishing for something to happen, although this is very unlikely |

III. Relative Clauses

Look at these sentences

(a) All morning Lencho — who knew his fields intimately — looked at the sky.

(b) The woman, who was preparing supper, replied, “Yes, God willing.’’

The italicised parts of the sentences give us more information about Lencho and the woman. We call them relative clauses. Notice that they begin with a relative pronoun who. Other common relative pronouns are whom, whose, and which.

The relative clauses in (a) and (b) above are called non-defining, because we already know the identity of the person they describe. Lencho is a particular person, and there is a particular woman he speaks to. We don’t need the information in the relative clause to pick these people out from a larger set.

A non-defining relative clause usually has a comma in front of it and a comma after it (some writers use a dash (—) instead, as in the story). If the relative clause comes at the end, we just put a full stop.

Join the sentences given below using who, whom, whose, which, as suggested.

1. I often go to Mumbai. Mumbai is the commercial capital of India. (which)

2. My mother is going to host a TV show on cooking. She cooks very well. (who)

3. These sportspersons are going to meet the President. Their performance has been excellent. (whose)

4. Lencho prayed to God. His eyes see into our minds. (whose)

5. This man cheated me. I trusted him. (whom)

Sometimes the relative pronoun in a relative clause remains ‘hidden’. For example, look at the first sentence of the story:

(a) The house — the only one in the entire valley — sat on the crest of a low hill.

We can rewrite this sentence as:

(b) The house — which was the only one in the entire valley — sat on the crest of a low hill.

In (a), the relative pronoun which and the verb was are not present.

IV. Using Negatives for Emphasis

We know that sentences with words such as no, not or nothing show theabsence of something, or contradict something. For example:

(a) This year we will have no corn. (Corn will be absent)

(b) The hail has left nothing. (Absence of a crop)

(c) These aren’t raindrops falling from the sky, they are new coins. (Contradicts the common idea of what the drops of water falling from the sky are)

But sometims negative words are used just to emphasise an idea. Look at these sentences from the story:

(d) Lencho...had done nothing else but see the sky towards the north- east. (He had done only this)

(e) The man went out for no other reason than to have the pleasure of feeling the rain on his body. (He had only this reason)

(f) Lencho showed not the slightest surprise on seeing the money. (He showed no surprise at all)

Now look back at example (c). Notice that the contradiction in fact serves to emphasise the value or usefulness of the rain to the farmer.

Find sentences in the story with negative words, which express the following ideas emphatically.

1. The trees lost all their leaves.

2. The letter was addressed to God himself.

3. The postman saw this address for the first time in his career.

V. Metaphors

The word metaphor comes from a Greek word meaning ‘transfer’. Metaphors compare two things or ideas: a quality or feature of one thing is transferred to another thing. Some common metaphors are

• the leg of the table: The leg supports our body. So the object that supports a table is described as a leg.

• the heart of the city: The heart is an important organ in the centre of our body. So this word is used to describe the central area of a city.

In pairs, find metaphors from the story to complete the table below. Try to say what qualities are being compared. One has been done for you.

| Object | Metaphor | Quality or Feature Compared |

|---|---|---|

| Cloud | Huge mountains of clouds | The mass or ‘hugeness’ of mountains |

| Raindrops | ||

| Hailstones | ||

| Locusts | ||

| An epidemic (a disease) that spreads very rapidly and leaves many people dead | ||

| An ox of a man |

Have you ever been in great difficulty, and felt that only a miracle could help you? How was your problem solved? Speak about this in class with your teacher.

Have you ever been in great difficulty, and felt that only a miracle could help you? How was your problem solved? Speak about this in class with your teacher.

| The writer apologises (says sorry) because | |

|---|---|

| The writer has sent this to the reader | |

| The writer sent it in the month of | |

| The reason for not writing earlier | ______________________________ |

| Sarah goes to | |

| Who is writing to whom? | |

| Where and when were they last together? |

WHAT WE HAVE DONE

• Introduced students to the story that they are going to read.

• Related a thought-provoking story about the nature of belief.

• Helped students, through an interesting activity, to understand something that happens in the story — how to send money using a money order.

• Guided them through the reading activity by providing periodic comprehension checks as they read, and checked for holistic understanding at the end of the reading activity.

• Provided interesting exercises to strengthen students’ grasp of the specific vocabulary found in the story, and also introduced them to related vocabulary.

• Explained specific areas of grammar — non-defining relative clauses and the use of negatives for emphasis — providing illustrations from the text, and exercises for practice.

• Explained what metaphors are, and helped students identify metaphors in the text by providing clues.

• Provided a context for authentic speaking.

• Provided an interesting listening activity.

Given below is the passage for listening activity

Bhatt House

256, Circuit Road

Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India

25 January 2006

Dear Arti,

How are you? I’m sorry I haven’t written for a very long time. I think I last sent you a birthday card in the month of September 2005.

We have just moved house (see our new address above). This is our new home. Sarah has just about started going to school. We have admitted her to ‘Little Feet’ as this is very close to our new home.

I’m sitting here by the window sill, writing to you. There is a slight drizzle outside and I’m reminded of the good times we had together at Bangalore last year.

Do write back. Love,

Jaya

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Before You Read: Encourage students to share their ideas about what will happen in the story.

Activity: Before filling out the form, get the students to read through the form and decide which parts they should fill out, and which parts will be filled in by the postal department. Ask a few students to volunteer to actually send a money order (the amount need not be large) and share the experience with the rest of the class.

Reading: Break the text up into manageable chunks for reading (three paragraphs, for example), and encourage students to read silently, on their own. Give them enough time to read, and then discuss what they have read before going on to the next portion. Use the ‘Oral Comprehension Checks’ in the appropriate places, and use the ‘Thinking about the Text’ questions at the end of the passage to help them go beyond the text.

Grammar: After they have done the exercise, ask students to make their own sentences with non-defining relative clauses — for example, ‘Meena, who’s a very clever girl, is always first in class.’ Or, ‘Our gardener, who knows a lot about plants, loves to talk about them.’

Speaking: Take the first turn — talk to the students about an instance from your own life, or from that of someone you know.

The way a crow

Shook down on me

The dust of snow

From a hemlock tree

Has given my heart

A change of mood

And saved some part

Of a day I had rued.

ROBERT FROST

hemlock: A poisonous plant (tree) with small white flowers

hemlock: A poisonous plant (tree) with small white flowersrued: held in regret

Fire and Ice