Table of Contents

Chapter -8

Novels, Society and History

In the previous chapter you read about the rise of print culture and how new forms of communication reshaped the way people thought about themselves or related to each other. You also saw how print culture created the possibility of new forms of literature. In this chapter we will study the history of one such form – the novel – a history that is closely connected to the making of modern ways of thinking. We will first look at the history of the novel in the West, and then see how this form developed in some of the regions of India. As you will see, despite their differences, there were many commonalites of focus between novels written in different parts of the world.

1 The Rise of the Novel

The novel is a modern form of literature. It is born from print, a mechanical invention.

We cannot think of the novel without the printed book. In ancient times, as you have seen (Chapter 7), manuscripts were handwritten. These circulated among very few people. In contrast, because of being printed, novels were widely read and became popular very quickly. At this time big cities like London were growing rapidly and becoming connected to small towns and rural areas through print and improved communications. Novels produced a number of common interests among their scattered and varied readers. As readers were drawn into the story and identified with the lives of fictitious characters, they could think about issues such as the relationship between love and marriage, the proper conduct for men and women, and so on.

The novel first took firm root in England and France. Novels began to be written from the seventeenth century, but they really flowered from the eighteenth century. New groups of lower-middle-class people such as shopkeepers and clerks, along with the traditional aristocratic and gentlemanly classes in England and France now formed the new readership for novels.

As readership grew and the market for books expanded, the earnings of authors increased. This freed them from financial dependence on the patronage of aristocrats, and gave them independence to experiment with different literary styles. Henry Fielding, a novelist of the early eighteenth century, claimed he was ‘the founder of a new province of writing’ where he could make his own laws. The novel allowed flexibility in the form of writing. Walter Scott remembered and collected popular Scottish ballads which he used in his historical novels about the wars between Scottish clans. The epistolary novel, on the other hand, used the private and personal form of letters to tell its story. Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, written in the eighteenth century, told much of its story through an exchange of letters between two lovers. These letters tell the reader of the hidden conflicts in the heroine’s mind.

New words

Gentlemanly classes – People who claimed noble birth and high social position. They were supposed to set the standard for proper behaviour

Epistolary – Written in the form of a series of letters

1.1 The Publishing Market

For a long time the publishing market excluded the poor. Initially, novels did not come cheap. Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (1749) was issued in six volumes priced at three shillings each – which was more than what a labourer earned in a week.

Fig. 1 – Cover page of Sketches by ‘Boz’.

Charles Dickens’s first publication was a collection of journalistic essays entitled Sketches by ‘Boz’ (1836).

But soon, people had easier access to books with the introduction of circulating libraries in 1740. Technological improvements in printing brought down the price of books and innovations in marketing led to expanded sales. In France, publishers found that they could make super profits by hiring out novels by the hour. The novel was one of the first mass-produced items to be sold. There were several reasons for its popularity. The worlds created by novels were absorbing and believable, and seemingly real. While reading novels, the reader was transported to another person’s world, and began looking at life as it was experienced by the characters of the novel. Besides, novels allowed individuals the pleasure of reading in private, as well as the joy of publicly reading or discussing stories with friends or relatives. In rural areas people would collect to hear one of them reading a novel aloud, often becoming deeply involved in the lives of the characters. Apparently, a group at Slough in England were very pleased to hear that Pamela, the heroine of Richardson’s popular novel, had got married in their village. They rushed out to the parish church and began to ring the church bells!

New words

Serialised – A format in which the story is published in instalments, each part in a new issue of a journal

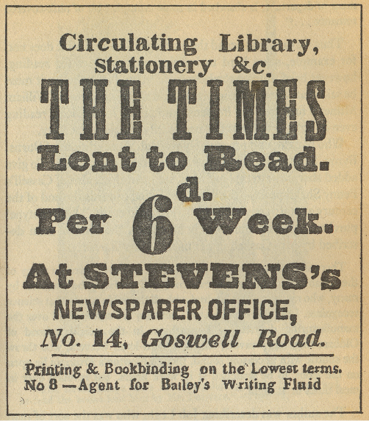

Fig. 2 – Library notice.

Libraries were well publicised.

Fig. 3 – Cover page of All The Year Round.

The most important feature of the magazine All the Year Round, edited by Charles Dickens, was his serialised novels. This particular issue begins with one.

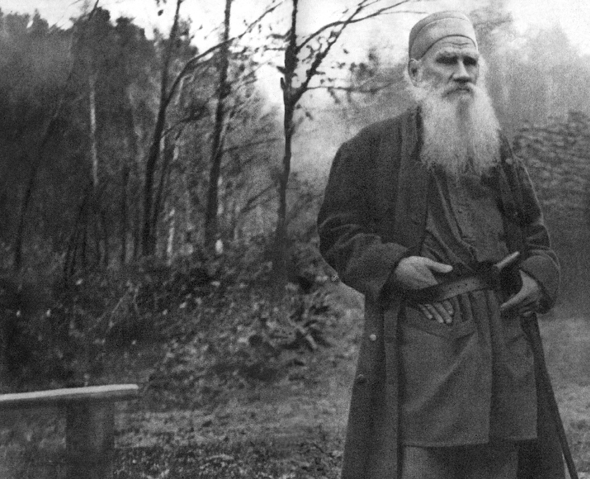

Fig. 4 – Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910).

Tolstoy was a famous Russian novelist who wrote extensively on rural life and community.

1.2 The World of the Novel

More than other forms of writing which came before, novels are about ordinary people. They do not focus on the lives of great people or actions that change the destinies of states and empires. Instead, they are about the everyday life of common people.

Fig. 5 – Charles Dickens (1812-1870).

Discuss

Explain what is meant by the following types of novels:

- Epistolary novel

- Serialised novel

For each type, name one writer who wrote in that style.

In the nineteenth century, Europe entered the industrial age. Factories came up, business profits increased and the economy grew. But at the same time, workers faced problems. Cities expanded in an unregulated way and were filled with overworked and underpaid workers. The unemployed poor roamed the streets for jobs, and the homeless were forced to seek shelter in workhouses. The growth of industry was accompanied by an economic philosophy which celebrated the pursuit of profit and undervalued the lives of workers. Deeply critical of these developments, novelists such as Charles Dickens wrote about the terrible effects of industrialisation on people’s lives and characters. His novel Hard Times (1854) describes Coketown, a fictitious industrial town, as a grim place full of machinery, smoking chimneys, rivers polluted purple and buildings that all looked the same. Here workers are known as ‘hands’, as if they had no identity other than as operators of machines. Dickens criticised not just the greed for profits but also the ideas that reduced human beings into simple instruments of production.

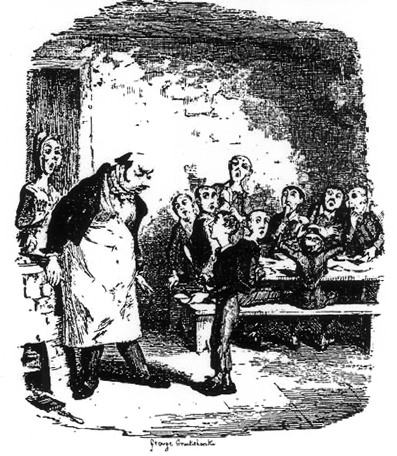

Fig. 6 – A hungry Oliver asks for more food while other children at the workhouse look on with fear, illustration in Oliver Twist.

In other novels too, Dickens focused on the terrible conditions of urban life under industrial capitalism. His Oliver Twist (1838) is the tale of a poor orphan who lived in a world of petty criminals and beggars. Brought up in a cruel workhouse (see Fig. 6), Oliver was finally adopted by a wealthy man and lived happily ever after. But not all novels about the lives of the poor gave readers the comfort of a happy ending. Emile Zola’s Germinal (1885) on the life of a young miner in France explores in harsh detail the grim conditions of miners’ lives. It ends on a note of despair: the strike the hero leads fails, his co-workers turn against him, and hopes are shattered.

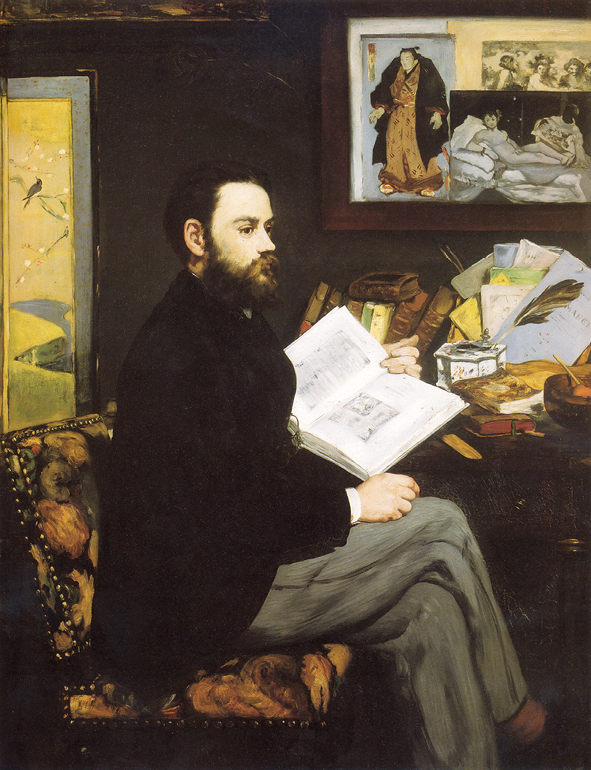

Fig. 7 – Emile Zola, painting by Edward Manet, 1868.

Manet’s portrait of the French author Zola, showing the novelist at his worktable in an intimate and thoughtful relationship with books.

1.3 Community and Society

The vast majority of readers of the novel lived in the city. The novel created in them a feeling of connection with the fate of rural communities. The nineteenth-century British novelist Thomas Hardy, for instance, wrote about traditional rural communities of England that were fast vanishing. This was actually a time when large farmers fenced off land, bought machines and employed labourers to produce for the market. The old rural culture with its independent farmers was dying out. We get a sense of this change in Hardy’s Mayor of Casterbridge (1886). It is about Michael Henchard, a successful grain merchant, who becomes the mayor of the farming town of Casterbridge. He is an independent-minded man who follows his own style in conducting business. He can also be both unpredictably generous and cruel with his employees. Consequently, he is no match for his manager and rival Donald Farfrae who runs his business on efficient managerial lines and is well regarded for he is smooth and even-tempered with everyone. We can see that Hardy mourns the loss of the more personalised world that is disappearing, even as he is aware of its problems and the advantages of the new order.

Fig. 8 – Thomas Hardy (1840-1928).

The novel uses the vernacular, the language that is spoken by common people. By coming closer to the different spoken languages of the people, the novel produces the sense of a shared world between diverse people in a nation. Novels also draw from different styles of language. A novel may take a classical language and combine it with the language of the streets and make them all a part of the vernacular that it uses. Like the nation, the novel brings together many cultures.

1.4 The New Woman

The most exciting element of the novel was the involvement of women. The eighteenth century saw the middle classes become more prosperous. Women got more leisure to read as well as write novels. And novels began exploring the world of women – their emotions and identities, their experiences and problems.

Many novels were about domestic life – a theme about which women were allowed to speak with authority. They drew upon their experience, wrote about family life and earned public recognition.

New words

Vernacular – The normal, spoken form of a language rather than the formal, literary form

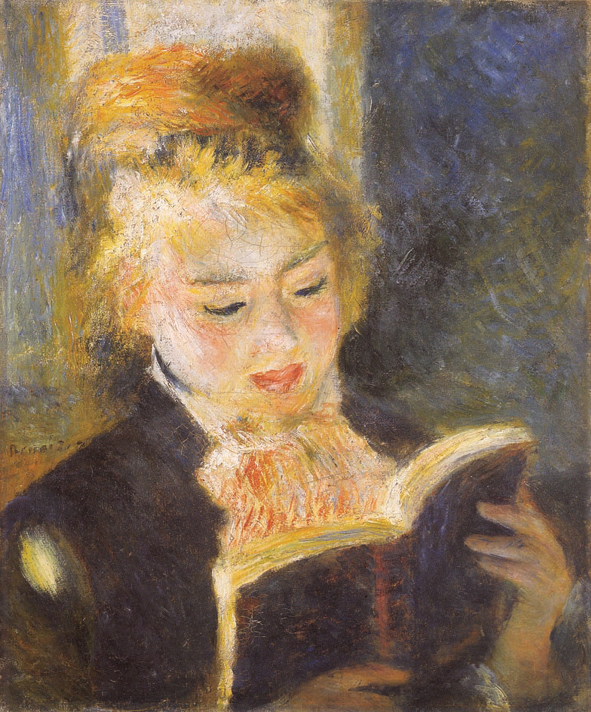

Fig. 9 – A girl reading, a painting by Jean Renoir (1841-1919).

By the nineteenth century, images of women reading silently, in the privacy of the room, became common in European paintings.

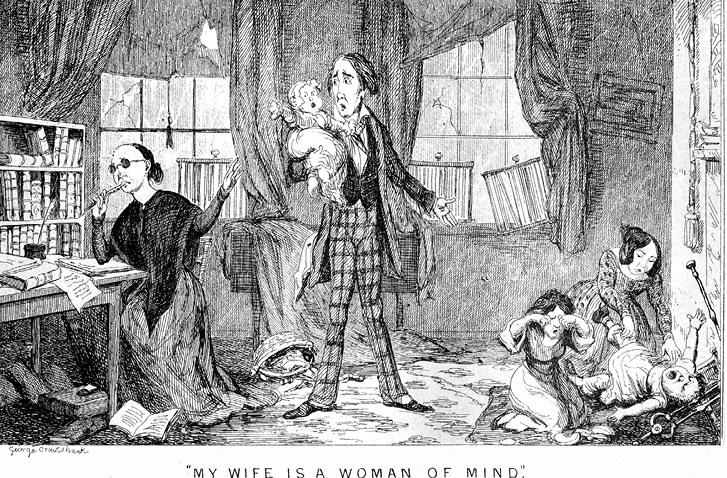

Fig. 10 – The home of a woman author, by George Cruikshank.

When women began writing novels many people feared that they would now neglect their traditional role as wives and mothers and homes would be in disorder.

The novels of Jane Austen give us a glimpse of the world of women in genteel rural society in early-nineteenth-century Britain. They make us think about a society which encouraged women to look for ‘good’ marriages and find wealthy or propertied husbands. The first sentence of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice states: ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.’ This observation allows us to see the behaviour of the main characters, who are preoccupied with marriage and money, as typifying Austen’s society.

Fig. 11 – Jane Austen (1775-1817).

But women novelists did not simply popularise the domestic role of women. Often their novels dealt with women who broke established norms of society before adjusting to them. Such stories allowed women readers to sympathise with rebellious actions. In Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, published in 1847, young Jane is shown as independent and assertive. While girls of her time were expected to be quiet and well behaved, Jane at the age of ten protests against the hypocrisy of her elders with startling bluntness. She tells her Aunt who is always unkind to her: ‘People think you a good woman, but you are bad ... You are deceitful! I will never call you aunt as long as I live.’

Fig. 12 – The marriage contract, William Hogarth (1697-1764).

As you can see, the two men in the foreground are busy with the signing of the marriage contract while the woman stays in the background.

Fig. 13 – Charlotte Bronte (1816-1855).

Box 1

Women novelists

George Eliot (1819-1880) was the pen-name of Mary Ann Evans. A very popular novelist, she believed that novels gave women a special opportunity to express themselves freely. Every woman could see herself as capable of writing fiction:

‘Fiction is a department of literature in which women can, after their kind, fully equal men … No educational restrictions can shut women from the materials of fiction, and there is no species of art that is so free from rigid requirements.’

George Eliot, ‘Silly novels by lady novelists’, 1856.

1.5 Novels for the Young

Novels for young boys idealised a new type of man: someone who was powerful, assertive, independent and daring. Most of these novels were full of adventure set in places remote from Europe. The colonisers appear heroic and honourable – confronting ‘native’ peoples and strange surroundings, adapting to native life as well as changing it, colonising territories and then developing nations there. Books like R.L. Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) or Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book (1894) became great hits.

Box 2

G.A. Henty (1832-1902):

In Under Drake’s Flag (1883) two young Elizabethan adventurers face their apparently approaching death, but still remember to assert their Englishness:

‘Well, Ned, we have had more good fortune than we could have expected. We might have been killed on the day when we landed, and we have spent six jolly months in wandering together as hunters on the plain. If we must die, let us behave like Englishmen and Christians.’

G.A. Henty’s historical adventure novels for boys were also wildly popular during the height of the British empire. They aroused the excitement and adventure of conquering strange lands. They were set in Mexico, Alexandria, Siberia and many other countries. They were always about young boys who witness grand historical events, get involved in some military action and show what they called ‘English’ courage.

Love stories written for adolescent girls also first became popular in this period, especially in the US, notably Ramona (1884) by Helen Hunt Jackson and a series entitled What Katy Did (1872) by Sarah Chauncey Woolsey, who wrote under the pen-name Susan Coolidge.

1.6 Colonialism and After

The novel originated in Europe at a time when it was colonising the rest of the world. The early novel contributed to colonialism by making the readers feel they were part of a superior community of fellow colonialists. The hero of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) is an adventurer and slave trader. Shipwrecked on an island, Crusoe treats coloured people not as human beings equal to him, but as inferior creatures. He rescues a ‘native’ and makes him his slave. He does not ask for his name but arrogantly gives him the name Friday. But at the time, Crusoe’s behaviour was not seen as unacceptable or odd, for most writers of the time saw colonialism as natural. Colonised people were seen as primitive and barbaric, less than human; and colonial rule was considered necessary to civilise them, to make them fully human. It was only later, in the twentieth century, that writers like Joseph Conrad (1857-1924) wrote novels that showed the darker side of colonial occupation.

The colonised, however, believed that the novel allowed them to explore their own identities and problems, their own national concerns. Let us see how the novel became popular in India and what significance it had for society.

2 The Novel Comes to India

Stories in prose were not new to India. Banabhatta’s Kadambari, written in Sanskrit in the seventh century, is an early example. The Panchatantra is another. There was also a long tradition of prose tales of adventure and heroism in Persian and Urdu, known as dastan.

However, these works were not novels as we know them today. The modern novel form developed in India in the nineteenth century, as Indians became familiar with the Western novel. The development of the vernaculars, print and a reading public helped in this process. Some of the earliest Indian novels were written in Bengali and Marathi. The earliest novel in Marathi was Baba Padmanji’s Yamuna Paryatan (1857), which used a simple style of storytelling to speak about the plight of widows. This was followed by Lakshman Moreshwar Halbe’s Muktamala (1861). This was not a realistic novel; it presented an imaginary ‘romance’ narrative with a moral purpose.

Box 3

Not all Marathi novels were realistic. Naro Sadashiv Risbud used a highly ornamental style in his Marathi novel Manjughosha (1868). This novel was filled with amazing events. Risbud had a reason behind his choice of style. He said:

‘Because of our attitude to marriage and for several other reasons one finds in the lives of the Hindus neither interesting views nor virtues … If we write about things that we experience daily there would be nothing enthralling about them, so that if we set out to write an entertaining book we are forced to take up with the marvellous.’

Leading novelists of the nineteenth century wrote for a cause. Colonial rulers regarded the contemporary culture of India as inferior. On the other hand, Indian novelists wrote to develop a modern literature of the country that could produce a sense of national belonging and cultural equality with their colonial masters.

Translations of novels into different regional languages helped to spread the popularity of the novel and stimulated the growth of the novel in new areas.

2.1 The Novel in South India

Fig. 14 – Chandu Menon (1847-1899).

Novels began appearing in south Indian languages during the period of colonial rule. Quite a few early novels came out of attempts to translate English novels into Indian languages. For example,

O. Chandu Menon, a subjudge from Malabar, tried to translate an English novel called Henrietta Temple written by Benjamin Disraeli into Malayalam. But he quickly realised that his readers in Kerala were not familiar with the way in which the characters in English novels lived: their clothes, ways of speaking, and manners were unknown to them. They would find a direct translation of an English novel dreadfully boring. So, he gave up this idea and wrote instead a story in Malayalam in the ‘manner of English novel books’. This delightful novel called Indulekha, published in 1889, was the first modern novel in Malayalam.

The case of Andhra Pradesh was strikingly similar. Kandukuri Viresalingam (1848-1919) began translating Oliver Goldsmith’s Vicar of Wakefield into Telugu. He abandoned this plan for similar reasons and instead wrote an original Telugu novel called Rajasekhara Caritamu in 1878.

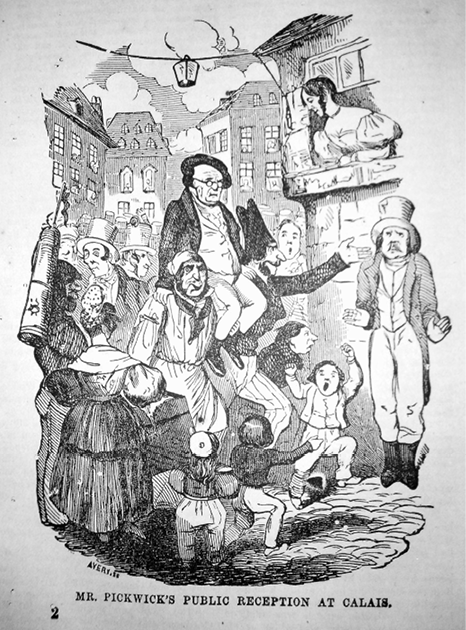

Fig. 15 – Image from Pickwick Abroad.

A drawing from the book Pickwick Abroad written by

G.W.M. Reynolds.

Minor nineteenth-century English novelists like Reynolds,

F. Marion Crawford and Marie Corelli were hugely popular in colonial India. Their novels – which were historical romances, adventure stories and sensation novels – were easily available and were translated and ‘adapted’ into several Indian languages. Reynolds’s Pickwick Abroad (1839) was more popular in India than Dickens’s original Pickwick Papers (1837).

2.2 The Novel in Hindi

In the north, Bharatendu Harishchandra, the pioneer of modern Hindi literature, encouraged many members of his circle of poets and writers to recreate and translate novels from other languages. Many novels were actually translated and adapted from English and Bengali under his influence, but the first proper modern novel was written by Srinivas Das of Delhi.

Srinivas Das’s novel, published in 1882, was titled Pariksha-Guru (The Master Examiner). It cautioned young men of well-to-do families against the dangerous influences of bad company and consequent loose morals.

Pariksha-Guru reflects the inner and outer world of the newly emerging middle classes. The characters in the novel are caught in the difficulty of adapting to colonised society and at the same time preserving their own cultural identity. The world of colonial modernity seems to be both frightening and irresistible to the characters. The novel tries to teach the reader the ‘right way’ to live and expects all ‘sensible men’ to be worldly-wise and practical, to remain rooted in the values of their own tradition and culture, and to live with dignity and honour.

Discuss

Write about two important characteristics of the early Hindi novel.

In the novel we see the characters attempting to bridge two different worlds through their actions: they take to new agricultural technology, modernise trading practices, change the use of Indian languages, making them capable of transmitting both Western sciences and Indian wisdom. The young are urged to cultivate the ‘healthy habit’ of reading the newspapers. But the novel emphasises that all this must be achieved without sacrificing the traditional values of the middle-class household. With all its good intentions, Pariksha-Guru could not win many readers, as it was perhaps too moralising in its style.

Box 4

The novel in Assam

The first novels in Assam were written by missionaries. Two of them were translations of Bengali including Phulmoni and Karuna. In 1888, Assamese students in Kolkata formed the Asamya Bhasar Unnatisadhan that brought out a journal called Jonaki. This journal opened up the opportunities for new authors to develop the novel. Rajanikanta Bardoloi wrote the first major historical novel in Assam called Manomati (1900). It is set in the Burmese invasion, stories of which the author had probably heard from old soldiers who had fought in the 1819 campaign. It is a tale of two lovers belonging to two hostile families who are separated by the war and finally reunited.

The writings of Devaki Nandan Khatri created a novel-reading public in Hindi. His best-seller, Chandrakanta – a romance with dazzling elements of fantasy – is believed to have contributed immensely in popularising the Hindi language and the Nagari script among the educated classes of those times. Although it was apparently written purely for the ‘pleasure of reading’, this novel also gives some interesting insights into the fears and desires of its reading public.

It was with the writing of Premchand that the Hindi novel achieved excellence. He began writing in Urdu and then shifted to Hindi, remaining an immensely influential writer in both languages. He drew on the traditional art of kissa-goi (storytelling). Many critics think that his novel Sewasadan (The Abode of Service), published in 1916, lifted the Hindi novel from the realm of fantasy, moralising and simple entertainment to a serious reflection on the lives of ordinary people and social issues. Sewasadan deals mainly with the poor condition of women in society. Issues like child marriage and dowry are woven into the story of the novel. It also tells us about the ways in which the Indian upper classes used whatever little opportunities they got from colonial authorities to govern themselves.

Fig. 16a – Lakshminath Bezbaruah (1868–1938)

He was a doyen of modern Assamese literature. Burhi Aair Sadhu (Grandma’s Tales) is among his notable works. He penned the popular song of Assam, ‘O Mor Apunar Desh’ (O’ my beloved land).

2.3 Novels in Bengal

In the nineteenth century, the early Bengali novels lived in two worlds. Many of these novels were located in the past, their characters, events and love stories based on historical events. Another group of novels depicted the inner world of domestic life in contemporary settings. Domestic novels frequently dealt with the social problems and romantic relationships between men and women.

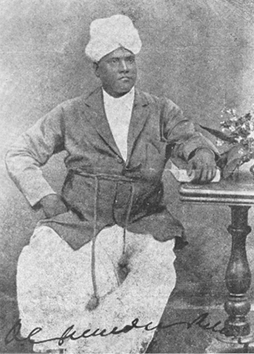

Fig. 16b – Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (1838-1894).

Bankim’s hands on the book indicates how writing was the basis of his social position and authority.

The old merchant elite of Calcutta patronised public forms of entertainment such as kabirlarai (poetry contests), musical soirees and dance performances. In contrast, the new bhadralok found himself at home in the more private world of reading novels.

Novels were read individually. They could also be read in select groups. Sometimes the household of the great Bangla novelist Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay would host a jatra in the courtyard where members of the family would be gathered. In Bankim’s room, however, a group of literary friends would collect to read, discuss and judge literary works. Bankim read out Durgeshnandini (1865),

his first novel, to such a gathering of people who were stunned to realise that the Bengali novel had achieved excellence so quickly.

Box 5

The Oriya novel

In 1877-78, Ramashankar Ray, a dramatist, began serialising the first Oriya novel, Saudamani. But he could not complete it. Within thirty years, however, Orissa produced a major novelist in Fakir Mohon Senapati (1843-1918). The title of his novel Chaa Mana Atha Guntha (1902) translates as six acres and thirty-two decimals of land. It announces a new kind of novel that will deal with the question of land and its possession. It is the story of Ramchandra Mangaraj, a landlord’s manager who cheats his idle and drunken master and then eyes the plot of fertile land owned by Bhagia and Shariya, a childless weaver couple. Mangaraj fools this couple and puts them into his debt so that he can take over their land. This pathbreaking work showed that the novel could make rural issues an important part of urban preoccupations. In writing this novel, Fakir Mohon anticipated a host of writers in Bengal and elsewhere.

Besides the ingenious twists and turns of the plot and the suspense, the novel was also relished for its language. The prose style became a new object of enjoyment. Initially the Bengali novel used a colloquial style associated with urban life. It also used meyeli, the language associated with women’s speech. This style was quickly replaced by Bankim’s prose which was Sanskritised but also contained a more vernacular style.

The novel rapidly acquired popularity in Bengal. By the twentieth century, the power of telling stories in simple language made Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay (1876-1938) the most popular novelist in Bengal and probably in the rest of India.

.png)

Fig. 17 – The temple and the drawing room.

On the right is the temple where the family and others would gather and on the left is the drawing room where Bankim would entertain select friends to discuss new literary works. Note that the two spaces – the traditional and the modern – are next to each other, indicating the split lifestyle of most intellectuals in colonial India.

3 Novels in the Colonial World

If we follow the history of the novel in different parts of India we can see many regional peculiarities. But there were also recurring patterns and common concerns. What inspired the authors to write novels? Who read the novels? How did the culture of reading develop? How did the novels grapple with the problems of societal change within a colonial society? What kind of a world did novels open up for the readers? Let us explore some of these questions by focusing primarily on the writings of three authors from different regions: Chandu Menon, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay and Premchand.

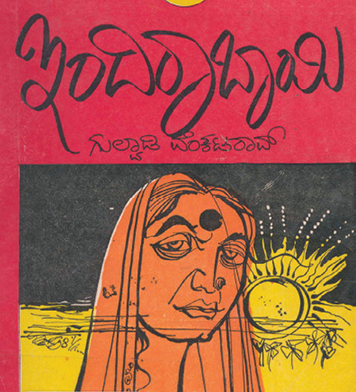

Fig. 18 – Cover page of the novel Indirabai.

Written at the end of the nineteenth century, Indirabai continues to be popular and is regularly reprinted. This is the cover of a recent reprint.

3.1 Uses of the Novel

Colonial administrators found ‘vernacular’ novels a valuable source of information on native life and customs. Such information was useful for them in governing Indian society, with its large variety of communities and castes. As outsiders, the British knew little about life inside Indian households. The new novels in Indian languages often had descriptions of domestic life. They showed how people dressed, their forms of religious worship, their beliefs and practices, and so on. Some of these books were translated into English, often by British administrators or Christian missionaries.

Indians used the novel as a powerful medium to criticise what they considered defects in their society and to suggest remedies. Writers like Viresalingam used the novel mainly to propagate their ideas about society among a wider readership.

Box 6

The message of reform

Many early novels carried a clear message of social reform. For example, in Indirabai, a Kannada novel written by Gulavadi Venkata Rao in 1899, the heroine is given away in marriage at a very young age to an elderly man. Her husband dies soon after, and she is forced to lead the life of a widow. In spite of opposition from her family and society, Indirabai succeeds in continuing her education. Eventually she marries again, this time a progressive, English-educated man. Women’s education, the plight of widows, and problems created by the early marriage of girls – all these were important issues for social reformers in Karnataka at that time.

Novels also helped in establishing a relationship with the past. Many of them told thrilling stories of adventures and intrigues set in the past. Through glorified accounts of the past, these novels helped in creating a sense of national pride among their readers.

At the same time, people from all walks of life could read novels so long as they shared a common language. This helped in creating a sense of collective belonging on the basis of one’s language.

Box 7

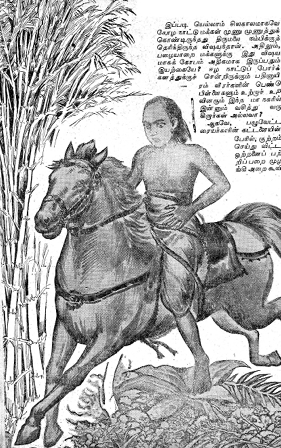

The most popular historical novelist in Tamil was R. Krishnamurthy who wrote under the pen-name ‘Kalki’. He was an active participant in the freedom movement and the editor of the widely read Tamil magazines Anandavikatan and Kalki. Written in simple language and full of heroism, adventure and suspense, Kalki’s novels captivated the Tamil-reading public of an entire generation.

Fig. 19 – A page from the novel Ponniyin Selvan, written by Kalki and serialised in the magazine Kalki, 1951.

You would have noticed that people living in different regions speak the same language in different ways – sometimes they use different words for the same thing; sometimes the same word is pronounced differently. With the coming of novels, such variations entered the world of print for the first time. The way characters spoke in a novel began to indicate their region, class or caste. Thus novels made their readers familiar with the ways in which people in other parts of their land spoke their language.

3.2 The Problem of Being Modern

Although they were about imaginary stories, novels often spoke to their readers about the real world. But novels did not always show things exactly as they were in reality. Sometimes, they presented a vision of how things ought to be. Social novelists often created heroes and heroines with ideal qualities, who their readers could admire and imitate. How were these ideal qualities defined? In many novels written during the colonial period, the ideal person successfully deals with one of the central dilemmas faced by colonial subjects: how to be modern without rejecting tradition, how to accept ideas coming from the West without losing one’s identity.

Chandu Menon portrayed Indulekha as a woman of breathtaking beauty, high intellectual abilities, artistic talent, and with an education in English and Sanskrit. Madhavan, the hero of the novel, was also presented in ideal colours. He was a member of the newly English-educated class of Nayars from the University of Madras. He was also a ‘first-rate Sanskrit scholar’. He dressed in Western clothes. But, at the same time, he kept a long tuft of hair, according to the Nayar custom.

The heroes and heroines in most of the novels were people who lived in the modern world. Thus they were different from the ideal or mythological characters of the earlier poetic literature of India. Under colonial rule, many of the English-educated class found new Western ways of living and thinking attractive. But they also feared that a wholesale adoption of Western values would destroy their traditional ways of living. Characters like Indulekha and Madhavan showed readers how Indian and foreign lifestyles could be brought together in an ideal combination.

3.3 Pleasures of Reading

As elsewhere in the world, in India too, the novel became a popular medium of entertainment among the middle class. The circulation of printed books allowed people to amuse themselves in new ways. Picture books, translations from other languages, popular songs sometimes composed on contemporary events, stories in newspapers and magazines – all these offered new forms of entertainment. Within this new culture of print, novels soon became immensely popular.

Fig. 20 – Cover page of Kathanjali, a Kannada magazine.

Kathanjali started publication in 1929 and published short stories regularly. The picture shows a mother reading out stories from a book to her children.

In Tamil, for example, there was a flood of popular novels in the early decades of the twentieth century. Detective and mystery novels often had to be printed again and again to meet the demand of readers: some of them were reprinted as many as twenty-two times!

The novel also assisted in the spread of silent reading. We are so used to reading in silence that it is difficult for us to think that this practice was not very common in the past. As late as the nineteenth century and perhaps even in the early twentieth century, written texts were often read aloud for several people to hear. Sometimes novels were also read in this way, but in general novels encouraged reading alone and in silence. Individuals sitting at home or travelling in trains enjoyed them. Even in a crowded room, the novel offered a special world of imagination into which the reader could slip, and be all alone. In this, reading a novel was like daydreaming.

4 Women and the Novel

Many people got worried about the effects of the novel on readers who were taken away from their real surroundings into an imaginary world where anything could happen. Some of them wrote in newspapers and magazines, advising people to stay away from the immoral influence of novels. Women and children were often singled out for such advice: they were seen as easily corruptible.

Fig. 21 – A woman reading, woodcut by Satyendranath Bishi.

The woodcut shows how women were discovering the pleasure of reading. By the end of the nineteenth century, images of women reading became common in popular magazines in India.

Some parents kept novels in the lofts in their houses, out of their children’s reach. Young people often read them in secret. This passion was not limited only to the youth. Older women – some of whom could not read – listened with fascinated attention to popular Tamil novels read out to them by their grandchildren – a nice reversal of the familiar grandma’s tales!

But women did not remain mere readers of stories written by men; soon they also began to write novels. In some languages, the early creations of women were poems, essays or autobiographical pieces. In the early decades of the twentieth century, women in south India also began writing novels and short stories. A reason for the popularity of novels among women was that it allowed for a new conception of womanhood. Stories of love – which was a staple theme of many novels – showed women who could choose or refuse their partners and relationships. It showed women who could to some extent control their lives. Some women authors also wrote about women who changed the world of both men and women.

Source A

Why women should not read novels

From a Tamil essay published in 1927:

‘Dear children, don’t read these novels, don’t even touch them. Your life will be ruined. You will suffer disease and ailments. Why did the good Lord make you – to wither away at a tender age? To suffer in disease? To be despised by your brothers, relatives and those around you? No. No. You must become mothers; you must lead happy lives; this is the divine purpose. You who were born to fulfil this sublime goal, should you ruin your life by going crazy after despicable novels?’

Essay by Thiru. Vi. Ka, Translated by A.R. Venkatachalapathy

Rokeya Hossein (1880-1932) was a reformer who, after she was widowed, started a girl’s school in Calcutta. She wrote a satiric fantasy in English called Sultana’s Dream (1905) which shows a topsy-turvy world in which women take the place of men. Her novel Padmarag also showed the need for women to reform their condition by their own actions.

New words

Satire – A form of representation through writing, drawing, painting, etc. that provides a criticism of society in a manner that is witty and clever

Box 8

Women with books

‘These days we can see women in black bordered sarees with massive books in their hands, walking inside their houses. Often seeing them with these books in hand, their brothers or husbands are seized with fear – in case they are asked for meanings.’

Sadharani, 1880.

It is not surprising that many men were suspicious of women writing novels or reading them. This suspicion cut across communities. Hannah Mullens, a Christian missionary and the author of Karuna o Phulmonir Bibaran (1852), reputedly the first novel in Bengali, tells her readers that she wrote in secret. In the twentieth century, Sailabala Ghosh Jaya, a popular novelist, could only write because her husband protected her. As we have seen in the case of the south, women and girls were often discouraged from reading novels.

4.1 Caste Practices, ‘Lower-Castes’ and Minorities

As you have seen, Indulekha was a love story. But it was also about an issue that was hotly debated at the time when the novel was written. This concerned the marriage practices of upper-caste Hindus in Kerala, especially the Nambuthiri Brahmins and the Nayars. Nambuthiris were also major landlords in Kerala at that time; and a large section of the Nayars were their tenants. In late-nineteenth-century Kerala, a younger generation of English-educated Nayar men who had acquired property and wealth on their own, began arguing strongly against Nambuthiri alliances with Nayar women. They wanted new laws regarding marriage and property.

The story of Indulekha is interesting in the light of these debates. Suri Nambuthiri, the foolish landlord who comes to marry Indulekha, is the focus of much satire in the novel. The intelligent heroine rejects him and chooses Madhavan, the educated and handsome Nayar as her husband, and the young couple move to Madras, where Madhavan joins the civil service. Suri Nambuthiri, desperate to find a partner for himself, finally marries a poorer relation from the same family and goes away pretending that he has married Indulekha! Chandu Menon clearly wanted his readers to appreciate the new values of his hero and heroine and criticise the ignorance and immorality of Suri Nambuthiri.

Novels like Indirabai and Indulekha were written by members of the upper castes, and were primarily about upper-caste characters. But not all novels were of this kind.

Fig. 22 – Malabar Beauty, painting by Ravi Varma.

Chandu Menon thought that the novel was similar to new trends in Indian painting.

One of the foremost oil painters of this time was Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906). Chandu Menon’s description of his heroines may have been guided by some of his paintings.

Potheri Kunjambu, a ‘lower-caste’ writer from north Kerala, wrote a novel called Saraswativijayam in 1892, mounting a strong attack on caste oppression. This novel shows a young man from an ‘untouchable’ caste, leaving his village to escape the cruelty of his Brahmin landlord. He converts to Christianity, obtains modern education, and returns as the judge in the local court. Meanwhile, the villagers, thinking that the landlord’s men had killed him, file a case. At the conclusion of the trial, the judge reveals his true identity, and the Nambuthiri repents and reforms his ways. Saraswativijayam stresses the importance of education for the upliftment of the lower castes.

From the 1920s, in Bengal too a new kind of novel emerged that depicted the lives of peasants and ‘low’ castes. Advaita Malla Burman’s (1914-51) Titash Ekti Nadir Naam(1956) is an epic about the Mallas, a community of fisherfolk who live off fishing in the river Titash. The novel is about three generations of the Mallas, about their recurring tragedies and the story of Ananta, a child born of parents who were tragically separated after their wedding night. Ananta leaves the community to get educated in the city. The novel describes the community life of the Mallas in great detail, their Holi and Kali Puja festivals, boat races, bhatiali songs, their relationships of friendship and animosity with the peasants and the oppression of the upper castes. Slowly the community breaks up and the Mallas start fighting amongst themselves as new cultural influences from the city start penetrating their lives. The life of the community and that of the river is intimately tied. Their end comes together: as the river dries up, the community dies too. While novelists before Burman had featured ‘low’ castes as their protagonists, Titash is special because the author is himself from a ‘low-caste’, fisherfolk community.

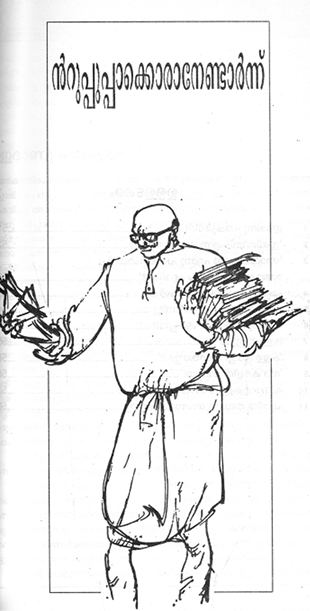

Fig. 23 – Basheer carrying books.

In his early years as a writer, Basheer had great difficulty earning a living from his books. He often sold them himself, carrying copies personally to houses and shops. In some of his stories, Basheer wrote about his days as a vendor of his own books.

Over time, the medium of the novel made room for the experiences of communities that had not received much space in the literary scene earlier. Vaikkom Muhammad Basheer (1908-94), for example, was one of the early Muslim writers to gain wide renown as a novelist in Malayalam.

Basheer had little formal education. Most of his works were based on his own rich personal experience rather than on books from the past. When he was in class five at school, Basheer left home to take part in the Salt Satyagraha. Later he spent years wandering in different parts of India and travelling even to Arabia, working in a ship, living with Sufis and Hindu sanyasis, and training as a wrestler.

Basheer’s short novels and stories were written in the ordinary language of conversation. With wonderful humour, Basheer’s novels spoke about details from the everyday life of Muslim households. He also brought into Malayalam writing themes which were considered very unusual at that time – poverty, insanity and life in prisons.

5 The Nation and its History

The history written by colonial historians tended to depict Indians as weak, divided, and dependent on the British. These histories could not satisfy the tastes of the new Indian administrators and intellectuals. Nor did the traditional Puranic stories of the past – peopled by gods and demons, filled with the fantastic and the supernatural – seem convincing to those educated and working under the English system. Such minds wanted a new view of the past that would show that Indians could be independent minded and had been so in history. The novel provided a solution. In it, the nation could be imagined in a past that also featured historical characters, places, events and dates.

Fig. 24 – Image from the film Chemmeen.

Many novels were made into films. The novel Chemmeen (Shrimp, 1956), written by Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai (1912-99), is set in the fishing community in Kerala, and characters speak a variety of Malayalam used by fisherfolk in the region. The film Chemmeen, directed by Ramu Kariat, was made in 1965.

In Bengal, many historical novels were about Marathas and Rajputs. These novels produced a sense of a pan-Indian belonging. They imagined the nation to be full of adventure, heroism, romance and sacrifice – qualities that could not be found in the offices and streets of the nineteenth-century world. The novel allowed the colonised to give shape to their desires. Bhudeb Mukhopadhyay’s (1827-94) Anguriya Binimoy (1857) was the first historical novel written in Bengal. Its hero Shivaji engages in many battles against a clever and treacherous Aurangzeb. Man Singh persuades Shivaji to make peace with Aurangzeb. Realising that Aurangzeb intended to confine him as a house prisoner, Shivaji escapes and returns to battle. What gives him courage and tenacity is his belief that he is a nationalist fighting for the freedom of Hindus.

Fig. 25 – A still from the Kannada film Chomana Dudi (Choma’s Drum, directed by

B.V. Karanth in 1975).

The film is based on a novel of the same title written in 1930 by the celebrated Kannada novelist Sivarama Karanth (1902-1997).

The imagined nation of the novel was so powerful that it could inspire actual political movements. Bankim’s Anandamath (1882) is a novel about a secret Hindu militia that fights Muslims to establish a Hindu kingdom. It was a novel that inspired many kinds of

freedom fighters.

Many of these novels also reveal the problems of thinking about the nation. Was India to be a nation of only a single religious community? Who had natural claims to belong to the nation?

5.1 The Novel and Nation Making

Imagining a heroic past was one way in which the novel helped in popularising the sense of belonging to a common nation. Another way was to include various classes in the novel so that they could be seen to belong to a shared world. Premchand’s novels, for instance, are filled with all kinds of powerful characters drawn from all levels of society. In his novels you meet aristocrats and landlords, middle-level peasants and landless labourers, middle-class professionals and people from the margins of society. The women characters are strong individuals, especially those who come from the lower classes and are not modernised. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Premchand rejected the nostalgic obsession with ancient history. Instead, his novels look towards the future without forgetting the importance of the past.

Box 9

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) developed the Bengali novel after Bankim’s death. His early novels were historical; he later shifted to writing stories about domestic relationships. He was mainly preoccupied with the condition of women and nationalism. Both concerns are featured in his Ghare Baire (1916) translated in 1919 as The Home and the World. The story is about Bimala, the wife of Nikhilesh, a liberal landlord who believes that he can save his country by patiently bettering the lives of its poor and marginal sections. But Bimala is attracted to Sandip, her husband’s friend and a firebrand extremist. Sandip is so completely dedicated to throwing out the British that he does not mind if the poor ‘low’ castes suffer and Muslims are made to feel like outsiders. By becoming a part of Sandip’s group, Bimala gets a sense of self-worth and self-esteem. Rabindranth also shows the contradictory effects of nationalist involvement for women. Bimala may be admired by the young males of the group but she cannot influence their decisions. Indeed she is used by Sandip to acquire funds for the movement. Tagore’s novels are striking because they make us rethink both man-woman relationships and nationalism.

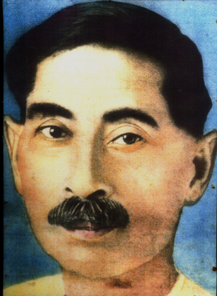

Fig. 26 – Portrait of Premchand (1880-1936).

Godan (The Gift of Cow), published in 1936, remains Premchand’s best-known work. It is an epic of the Indian peasantry. The novel tells the moving story of Hori and his wife Dhania, a peasant couple. Landlords, moneylenders, priests and colonial bureaucrats – all those who hold power in society – form a network of oppression, rob their land and make them into landless labourers. Yet Hori and Dhania retain their dignity to the end.

Activity

Read Godan. Write briefly on:

- How Premchand depicts the life of peasants in the novel.

- What the novel tells us about the life of peasants during the Great Depression.

Conclusion

We have seen how, over the course of its history in both the West and in India, the novel became part of the lives of different sections of people. Developments in print technologies allowed the novel to break out of its small circle of readers and introduced fresh ways of reading. But through their stories, novels have also shown a capacity to include and focus on the lives of those who were not often known to literate and middle-class circles. We have seen some examples of these in Premchand, but they are equally present in the works of other novelists.

Bringing together people from varied backgrounds produces a sense of shared community. The most notable form of this community is the nation. Equally significant is the fact that by bringing in both the powerful and the marginal peoples and cultures, the novel throws up many questions about the nature of these communities. We can say then that novels produce a sense of sharing, and promote an understanding of different people, different values and different communities. At the same time they explore how different groups begin to question or reflect upon their own identities.

Write in brief

1. Explain the following:

a) Social changes in Britain which led to an increase in women readers

b) What actions of Robinson Crusoe make us see him as a typical coloniser.

c) After 1740, the readership of novels began to include poorer people.

d) Novelists in colonial India wrote for a political cause.

2. Outline the changes in technology and society which led to an increase in readers of the novel in eighteenth-century Europe.

3. Write a note on:

a) The Oriya novel

b) Jane Austen’s portrayal of women

c) The picture of the new middle class which the novel Pariksha-Guru portrays.

Discuss

1. Discuss some of the social changes in nineteenth-century Britain which Thomas Hardy and Charles Dickens wrote about.

2. Summarise the concern in both nineteenth-century Europe and India about women reading novels. What does this suggest about how women were viewed?

3. In what ways was the novel in colonial India useful for both the colonisers as well as the nationalists?

4. Describe how the issue of caste was included in novels in India. By referring to any two novels, discuss the ways in which they tried to make readers think about existing social issues.

5. Describe the ways in which the novel in India attempted to create a sense of pan-Indian belonging.

Project

Imagine that you are a historian in 3035 AD. You have just located two novels which were written in the twentieth century. What do they tell you about society and customs of the time?