Table of Contents

5

Popular Struggles and Movements

Overview

In the earlier chapters we discussed why power sharing is important in a democracy and how different tiers of government and various social groups share power. In this chapter we will carry this discussion further and see how those who exercise power are constrained by the influence and pressure exerted on them. Democracy almost invariably involves conflict of interests and viewpoints. These differences are often expressed in organised ways. Those who are in power are required to balance these conflicting demands and pressures. We begin this chapter with a discussion of how struggles around conflicting demands and pressures shape democracy. This leads to an analysis of the different ways and organisations through which ordinary citizen can play a role in democracy. In this chapter, we look at the indirect ways of influencing politics, through pressure groups and movements. This leads us in the next chapter to the direct ways of controlling political power in the form of political parties.

Popular struggles in Nepal and Bolivia

Do you remember the story of the triumph of democracy in Poland? We studied it last year in the first chapter of class IX. The story reminded us about the role played by the people in the making of democracy. Let us read two recent stories of that kind and see how power is exercised in democracy.

Movement for democracy in Nepal

Nepal witnessed an extraordinary popular movement in April 2006. The movement was aimed at restoring democracy. Nepal, you might recall, was one of the ‘third wave’ countries that had won democracy in 1990. Although the king formally remained the head of the state, the real power was exercised by popularly elected representatives. King Birendra, who has accepted this transition from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy, was killed in a mysterious massacre of the royal family in 2001. King Gyanendra, the new king of Nepal, was not prepared to accept democratic rule. He took advantage of the weakness and unpopularity of the democratically elected government. In February 2005, the king dismissed the then Prime Minister and dissolved the popularly elected Parliament. The movement of April 2006 was aimed at regaining popular control over the government from

the king.

Political parties and people of Nepal in a rally demanding restoration of democracy in their country

All the major political parties in the parliament formed a Seven Party Alliance (SPA) and called for a four-day strike in Kathmandu, the country’s capital. This protest soon turned into an indefinite strike in which Maoist insurgents and various other organisations joined hands. People defied curfew and took to the streets. The security forces found themselves unable to take on more than a lakh people who gathered almost every day to demand restoration of democracy. The number of protesters reached between three and five lakhs on 21 April and they served an ultimatum to the king. The leaders of the movement rejected the half- hearted concessions made by the king. They stuck to their demands for restoration of parliament, power to

an all-party government and a new constituent assembly.

Maoists: Those communists who believe in the ideology of Mao, the leader of the Chinese Revolution. They seek to overthrow the government through an armed revolution so as to establish the rule of the peasants and workers.

Maoists: Those communists who believe in the ideology of Mao, the leader of the Chinese Revolution. They seek to overthrow the government through an armed revolution so as to establish the rule of the peasants and workers.

On 24 April 2006, the last day of the ultimatum, the king was forced to concede all the three demands. The SPA chose Girija Prasad Koirala as the new Prime Minister of the interim government. The restored parliament met and passed laws taking away most of the powers of the king. The SPA and the Maoists came to an understanding about how the new Constituent Assembly was going to be elected. In 2008, the monarchy was abolished and Nepal became a federal democratic republic. In 2015, it adopted a new constitution. The struggle of the Nepali people is a source of inspiration to democrats all over the world.

Bolivia’s Water War

The story of Poland and that of Nepal apply to the struggle for establishing or restoring democracy. But the role of popular struggles does not come to an end with the establishment of democracy. People’s successful struggle against privatisation of water in Bolivia reminds us that popular struggles are integral to the working of democracy.

Bolivia is a poor country in Latin America. The World Bank pressurised the government to give up its control of municipal water supply. The government sold these rights for the city of Cochabamba to a multi-national company (MNC). The company immediately increased the price of water by four times. Many people received monthly water bill of Rs 1000 in a country where average income is around Rs 5000 a month. This led to a spontaneous popular protest.

Are you suggesting that strike, dharna, bandh and demonstration are good for democracy?

In January 2000, a new alliance of labour, human rights and community leaders organised a successful four-day general strike in the city. The government agreed to negotiate and the strike was called off. Yet nothing happened. The police resorted to brutal repression when the agitation was started again in February. Another strike followed in April and the government imposed martial law. But the power of the people forced the officials of the MNC to flee the city and made the government concede to all the demands of the protesters. The contract with the MNC was cancelled and water supply was restored to the municipality at old rates. This came to be known as Bolivia’s water war.

Democracy and popular struggles

These two stories are from very different contexts. The movement in Nepal was to establish democracy, while the struggle in Bolivia involved claims on an elected, democratic government. The popular struggle in Bolivia was about one specific policy, while the struggle in Nepal was about the foundations of the country’s politics. Both these struggles were successful but their impact was at different levels.

Despite these differences, both the stories share some elements which are relevant to the study of the past and future of democracies. Both these are instances of political conflict that led to popular struggles. In both cases the struggle involved mass mobilisation. Public demonstration of mass support clinched the dispute. Finally, both instances involved critical role of political organisations. If you recall the first chapter of Class IX textbook, this is how democracy has evolved all over the world. We can, therefore, draw a few conclusions from these examples:

Democracy evolves through popular struggles. It is possible that some significant decisions may take place through consensus and may not involve any conflict at all. But that would be an exception. Defining moments of democracy usually involve conflict between those groups who have exercised power and those who aspire for a share in power. These moments come when the country is going through transition to democracy, expansion of democracy or deepening of democracy.

In 1984, the Karnataka government set up a company called Karnataka Pulpwood Limited. About 30,000 hectares of land was given virtually free to this company for 40 years. Much of this land was used by local farmers as grazing land for their cattle. However the company began to plant eucalyptus trees on this land, which could be used for making paper pulp. In 1987, a movement called Kittiko-Hachchiko (meaning, pluck and plant) started a non-violent protest, where people plucked the eucalyptus plants and planted saplings of trees that were useful to the people.

Suppose you belong to any of the following groups, what arguments would you put forward to defend your side: a local farmer, an environmental activist, a government official working in this company or just a consumer of paper.

Democratic conflict is resolved through mass mobilisation. Sometimes it is possible that the conflict is resolved by using the existing institutions like the parliament or the judiciary. But when there is a deep dispute, very often these institutions themselves get involved in the dispute. The resolution has to come from outside, from the people.

Does it mean that whichever side manages to mobilise a bigger crowd gets away with whatever it wants? Are we saying that ‘Might is Right’ in a democracy?

These conflicts and mobilisations are based on new political organisations. True, there is an element of spontaneity in all such historic moments. But the spontaneous public participation becomes effective with the help of organised politics. There can be many agencies of organised politics. These include political parties, pressure groups and movement groups.

Mobilisation and organisations

Let us go back to our two examples and look at the organisations that made these struggles successful. We noted that the call for indefinite strike was given by the SPA or the Seven Party Alliance in Nepal. This alliance included some big parties that had some members in the Parliament. But the SPA was not the only organisation behind this mass upsurge. The protest was joined by the Nepalese Communist Party (Maoist) which did not believe in parliamentary democracy. This party was involved in an armed struggle against the Nepali government and had established its control over large parts of Nepal.

The struggle involved many organisations other than political parties. All the major labour unions and their federations joined this movement. Many other organisations like the organisation of the indigenous people, teachers, lawyers and human rights groups extended support to the movement.

I don’t like this word ‘mobilisation’. Makes it feel as if people are like sheep.

The protest against water privatisation in Bolivia was not led by any political party. It was led by an organisation called FEDECOR. This organisation comprised local professionals, including engineers and environmentalists. They were supported by a federation of farmers who relied on irrigation, the confederation of factory workers’ unions, middle class students from the the University of Cochabamba and the city’s growing population of homeless street children. The movement was supported by the Socialist Party. In 2006, this party came to power in Bolivia.

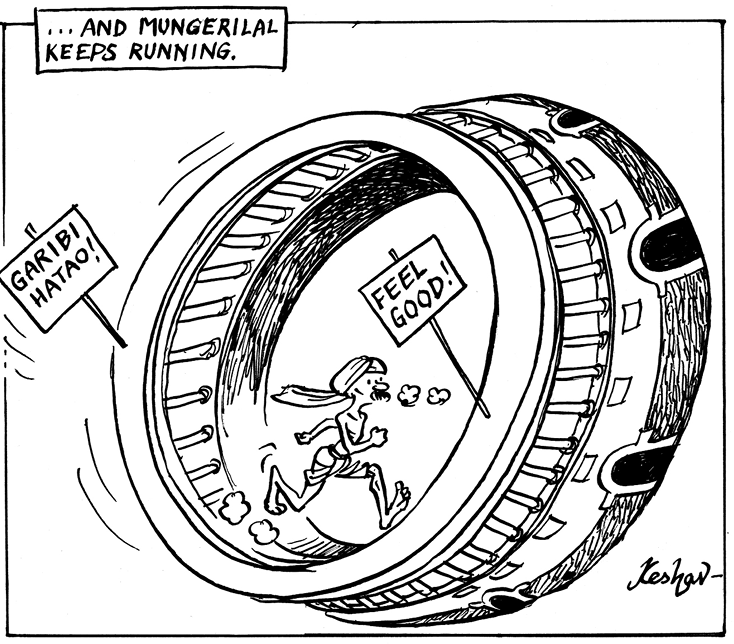

Governments initiate schemes and programmes to alleviate the suffering of the poor and meet their basic needs. But poverty remains in the country. What could be the reasons for such a situation?

From both these examples, we can see that in a democracy several different kinds of organisations work behind any big struggle. These organisations play their role in two ways. One obvious way of influencing the decisions in a democracy is direct participation in competitive politics. This is done by creating parties, contesting elections and forming governments. But every citizen does not participate so directly. They may not have the desire, the need or the skills to take part in direct political activity other than voting.

There are many indirect ways in which people can get governments to listen to their demands or their points of view. They could do so by forming an organisation and undertaking activities to promote their interests or their viewpoints. These are called interest groups or pressure groups. Sometimes people decide to act together without forming organisations.

Can you identify the pressure groups functioning in the news clippings given here? What demand are they making?

Pressure groups and movements

In the course of the discussion above we came across entities that are not quite an organisation. The struggle in Nepal was called a movement for democracy. We often hear the word people’s movement to describe many forms of collective action: Narmada Bachao Andolan, Movement for Right to Information, Anti-liquor Movement, Women’s Movement, Environmental Movement. Like an interest group, a movement also attempts to influence politics rather than directly take part in electoral competition. But unlike the interest groups, movements have a loose organisation. Their decision making is more informal and flexible. They depend much more on spontaneous mass participation than an interest group.

Land rights protest: farmers of West Java, Indonesia. In June 2004, about 15,000 landless farmers from West Java, travelled to Jakarta, the capital city. They came with their families to demand land reform, to insist on the return of their farms. Demonstrators chanted, “No land, No vote” declaring that they would boycott Indonesia’s first direct presidential election if no candidate backed land reform.

Sectional interest groups and public interest groups

Usually interest groups seek to promote the interests of a particular section or group of society. Trade unions, business associations and professional (lawyers, doctors, teachers, etc.) bodies are some examples of this type. They are sectional because they represent a section of society: workers, employees, business-persons, industrialists, followers of a religion, caste group, etc. Their principal concern is the betterment and well-being of their members, not society in general.

Sometimes these organisations are not about representing the interest of one section of society. They represent some common or general interest that needs to be defended. The members of the organisation may not benefit from the cause that the organisation represents. The Bolivian organisation, FEDECOR is an example of that kind of an organisation. In the context of Nepal, we noted the participation of human rights organisations. We read about these organisations in Class IX.

These second type of groups are called promotional groups or public interest groups. They promote collective rather than selective good. They aim to help groups other than their own members. For example, a group fighting against bonded labour fights not for itself but for those who are suffering under such bondage. In some instances the members of a public interest group may undertake activity that benefits them as well as others too. For example, BAMCEF (Backward and Minority Communities Employees Federation) is an organisation largely made up of government employees that campaigns against caste discrimination. It addresses the problems of its members who suffer discrimination. But its principal concern is with social justice and social equality for the entire society.

Movement groups

As in the case of interest groups, the groups involved with movements also include a very wide variety. The various examples mentioned above already indicate a simple distinction. Most of the movements are issue-specific movements that seek to achieve a single objective within a limited time frame. Others are more general or generic movements that seek to achieve a broad goal in the very long term.

The Nepalese movement for democracy arose with the specific objective of reversing the king’s orders that led to suspension of democracy. In India, Narmada Bachao Andolan is a good example of this kind of movement. The movement started with the specific issue of the people displaced by the creation of Sardar Sarovar dam on the Narmada river. Its objective was to stop the dam from being constructed. Gradually it became a wider movement that questioned all such big dams and the model of development that required such dams. Movements of this kind tend to have a clear leadership and some organisation. But their active life is usually short.

These single-issue movements can be contrasted with movements that are long term and involve more than one issue. The environmental movement and the women’s movement are examples of such movements. There is no single organisation that controls or guides such movements. Environmental movement is a label for a large number of organisations and issue-specific movements. All of these have separate organisations, independent leadership and often different views on policy related matters. Yet all of these share a broad objective and have a similar approach. That is why they are called a movement. Sometimes these broad movements have a loose umbrella organisation as well. For example, the National Alliance for Peoples’ Movements (NAPM) is an organisation of organisations. Various movement groups struggling on specific issues are constituents of this loose organisation which coordinates the activities of a large number of peoples’ movements in our country.

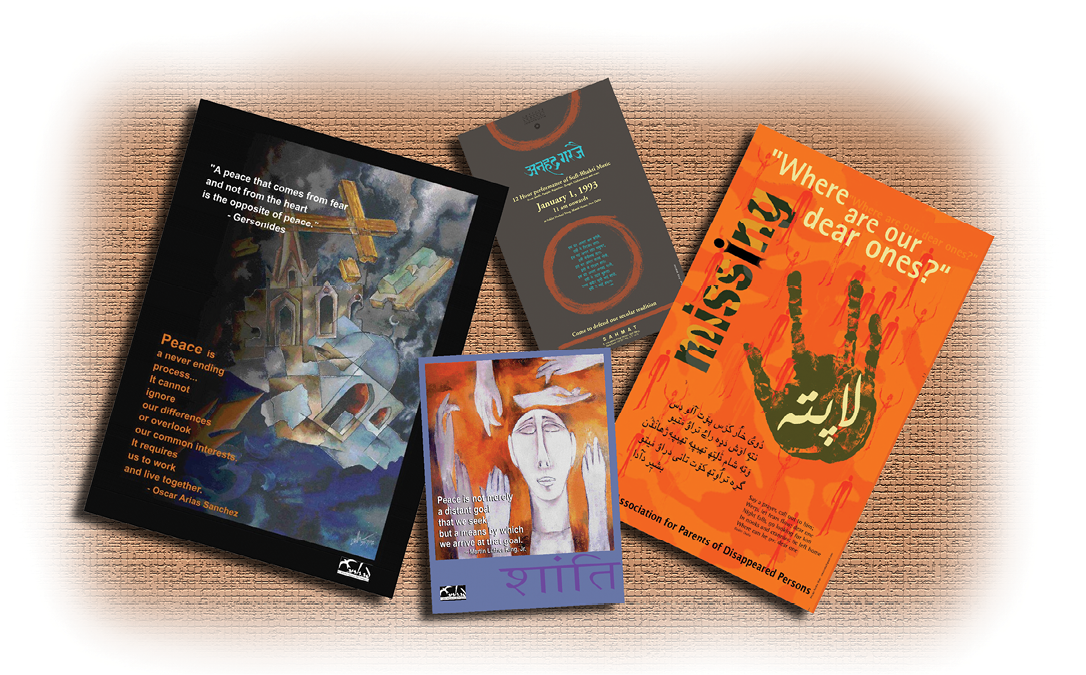

Social movements and pressure groups try to mobilise citizens in many ways. The collage here shows some of them.

How do they influence politics?

Pressure groups and movements exert influence on politics in a variety of ways:

They try to gain public support and sympathy for their goals and their activities by carrying out information campaigns, organising meetings, filing petitions, etc. Most of these groups try to influence the media into giving more attention to these issues.

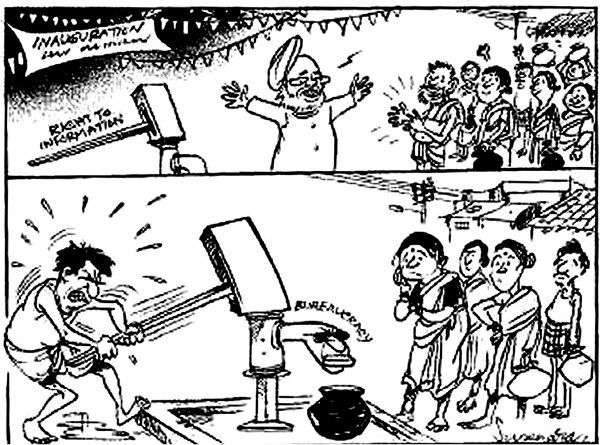

Many democratic governments provide the Right to Information (RTI) to the citizens. The RTI Act, 2005 is a landmark legislation passed by our Parliament. Under this Act, citizens can seek information from government offices pertaining to different activities.

Do you think the cartoon exaggerates the obstructionist role of bureaucracy in the implementation of the Act?

What are the social movements listed in these news clippings? What efforts are they making? Which sections are they trying to mobilise?

They often organise protest activity like strikes or disrupting government programmes. Workers’ organisations, employees’ associations and most of the movement groups often resort to these tactics in order to force the government to take note of their demands.

Business groups often employ professional lobbyists or sponsor expensive advertisements. Some persons from pressure groups or movement groups may participate in official bodies and committees that offer advice to the government.

While interest groups and movements do not directly engage in party politics, they seek to exert influence on political parties. Most of the movement groups take a political stance without being a party. They have political ideology and political position on major issues. The relationship between political parties and pressure groups can take different forms, some direct and others very indirect:

In some instances, the pressure groups are either formed or led by the leaders of political parties or act as extended arms of political parties. For example, most trade unions and students’ organisations in India are either established by, or affiliated to one or the other major political party. Most of the leaders of such pressure groups are usually activists and leaders of party.

Sometimes political parties grow out of movements. For example, when the Assam movement led by students against the ‘foreigners’ came to an end, it led to the formation of the Asom Gana Parishad. The roots of parties like the DMK and the AIADMK in Tamil Nadu can be traced to a long-drawn social reform movement during the 1930s and 1940s.

In most cases the relationship between parties and interest or movement groups is not so direct. They often take positions that are opposed to each other. Yet they are in dialogue and negotiation. Movement groups have raised new issues that have been taken up by political parties. Most of the new leadership of political parties comes from interest or movement groups.

Is their influence healthy?

It may initially appear that it is not healthy for groups that promote interest of one section to have influence in democracy. A democracy must look after the interests of all, not just one section. Also, it may seem that these groups wield power without responsibility. Political parties have to face the people in elections, but these groups are not accountable to the people. Pressure groups and movements may not get their funds and support from the people. Sometimes, pressure groups with small public support but lots of money can hijack public discussion in favour of their narrow agenda.

On balance, however, pressure groups and movements have deepened democracy. Putting pressure on the rulers is not an unhealthy activity in a democracy as long as everyone gets this opportunity. Governments can often come under undue pressure from a small group of rich and powerful people. Public interest groups and movements perform a useful role of countering this undue influence and reminding the government of the needs and concerns of ordinary citizens.

Even the sectional interest groups play a valuable role. Where different groups function actively, no one single group can achieve dominance over society. If one group brings pressure on government to make policies in its favour, another will bring counter pressure not to make policies in the way the first group desires. The government gets to hear about what different sections of the population want. This leads to a rough balance of power and accommodation of conflicting interests.

The Green Belt Movement has planted 30 million trees across Kenya. Its leader Wangari Maathai is very disappointed with the response of government officials and politicians:

The Green Belt Movement has planted 30 million trees across Kenya. Its leader Wangari Maathai is very disappointed with the response of government officials and politicians:

“In the 1970s and 1980s, as I was encouraging farmers to plant trees on their land, I also discovered that corrupt government agents were responsible for much of the deforestation by illegally selling off land and trees to well-connected developers. In the early 1990’s, the livelihoods, the rights and even the lives of many Kenyans in the Rift Valley were lost when elements of President Daniel Arap Moi’s government encouraged ethnic communities to attack one another over land. Supporters of the ruling party got the land, while those in the pro-democracy movement were displaced. This was one of the government’s ways of retaining power; if communities were kept busy fighting over land, they would have less opportunity to demand democracy.”

In the above passage what relationship do you see between democracy and social movements? How should this movement respond to the government?

This cartoon is called ‘News and No News’. Who is most often visible in the media? Whom are we most likely to hear about in newspapers?

2. Describe the forms of relationship between pressure groups and political parties?

3. Explain how the activities of pressure groups are useful in the functioning of a democratic government.

4. What is a pressure group? Give a few examples.

5. What is the difference between a pressure group and a political party?

6. Organisations that undertake activities to promote the interests of specific social sections such as workers, employees, teachers, and lawyers are called _____________________ groups.

7. Which among the following is the special feature that distinguishes a pressure group from a political party?

(a) Parties take political stances, while pressure groups do not bother about political issues.

(b) Pressure groups are confined to a few people, while parties involve larger number of people.

(c) Pressure groups do not seek to get into power, while political parties do.

(d) Pressure groups do not seek to mobilise people, while parties do.

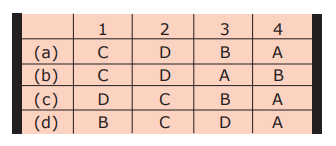

8. Match List I (organisations and struggles) with List II and select the correct answer using the codes given below the lists:

| List I | List II | |

| 1. | Organisations that seek to promote the interests of a particular section or group | A. Movement |

| 2. | Organisations that seek to promote common interest | B. Political parties |

| 3. | Struggles launched for the resolution of a social problem with or without an organisational structure | C. Sectional interest groups |

| 4. | Organisations that mobilise people with a view to win political power | D. Public interest groups |

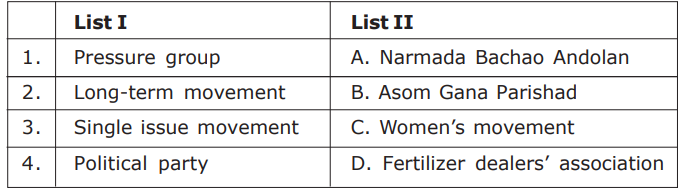

9. Match List I with List II and select the correct answer using the codes given below the lists:

10. Consider the following statements about pressure groups and parties.

A. Pressure groups are the organised expression of the interests and views of specific social sections.

B. Pressure groups take positions on political issues.

C. All pressure groups are political parties.

Which of the statements given above are correct?

(a) A, B, and C (b) A and B (c) B and C (d) A and C

11. Mewat is one of the most backward areas in Haryana. It used to be a part of two districts, Gurgaon and Faridabad. The people of Mewat felt that the area will get better attention if it were to become a separate district. But political parties were indifferent to this sentiment. The demand for a separate district was raised by Mewat Educational and Social Organisation and Mewat Saksharta Samiti in 1996. Later, Mewat Vikas Sabha was founded in 2000 and carried out a series of public awareness campaigns. This forced both the major parties, Congress and the Indian National Lok Dal, to announe their support for the new district before the assembly elections held in February 2005. The new district came into existence in July 2005.

In this example what is the relationship that you observe among movement, political parties and the government? Can you think of an example that shows a relationship different from this one?