Table of Contents

8

Challenges to Democracy

Overview

This concluding chapter draws upon all that you have learnt in the last two years so as to address the fundamental questions of democratic politics : What are the challenges that democracy faces in our country and elsewhere? What can be done to reform democratic politics? How can our democracy become more democratic in its practice and outcomes? This chapter does not answer these questions. It only makes some suggestions about the way in which we can approach the questions of challenges and reforms. It invites you to think on your own and come up with your own reading of the challenges, your recipe of how to overcome these and your own definition of democracy.

This concluding chapter draws upon all that you have learnt in the last two years so as to address the fundamental questions of democratic politics : What are the challenges that democracy faces in our country and elsewhere? What can be done to reform democratic politics? How can our democracy become more democratic in its practice and outcomes? This chapter does not answer these questions. It only makes some suggestions about the way in which we can approach the questions of challenges and reforms. It invites you to think on your own and come up with your own reading of the challenges, your recipe of how to overcome these and your own definition of democracy.Thinking about challenges

Do you remember the chapters of your Political Science textbook of Class IX? There we tracked the expansion of democracy all over the world . Our reading thereafter has confirmed our initial impression: democracy is the dominant form of government in the contemporary world. It does not face a serious challenger or rival. Yet our exploration of the various dimensions of democratic politics has shown us something else as well. The promise of democracy is far from realised anywhere in the world. Democracy does not have a challenger, but that does not mean that it does not face any challenges.

At different points in this tour of democracy, we have noted the serious challenges that democracy faces all over the world. A challenge is not just any problem. We usually call only those difficulties a ‘challenge’ which are significant and which can be overcome. A challenge is a difficulty that carries within it an opportunity for progress. Once we overcome a challenge we go up to a higher level than before.

Different countries face different kinds of challenges. At least one fourth of the globe is still not under democratic government. The challenge for democracy in these parts of the world is very stark. These countries face the foundational challenge of making the transition to democracy and then instituting democratic government. This involves bringing down the existing non-democratic regime, keeping military away from controlling government and establishing a sovereign and functional state.

Most of the established democracies face the challenge of expansion. This involves applying the basic principle of democratic government across all the regions, different social groups and various institutions. Ensuring greater power to local governments, extension of federal principle to all the units of the federation, inclusion of women and minority groups, etc., falls under this challenge. This also means that less and less decisions should remain outside the arena of democratic control. Most countries including India and other democracies like the US face this challenge.

The third challenge of deepening of democracy is faced by every democracy in one form or another. This involves strengthening of the institutions and practices of democracy. This should happen in such a way that people can realise their expectations of democracy. But ordinary people have different expectations from democracy in different societies. Therefore, this challenge takes different meanings and paths in different parts of the world. In general terms, it usually means strengthening those institutions that help people’s participation and control. This requires an attempt to bring down the control and influence of the rich and powerful people in making governmental decision.

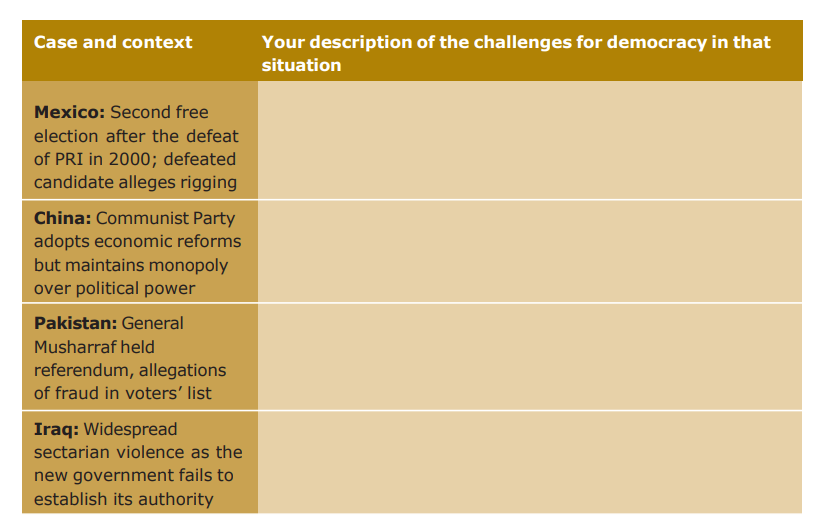

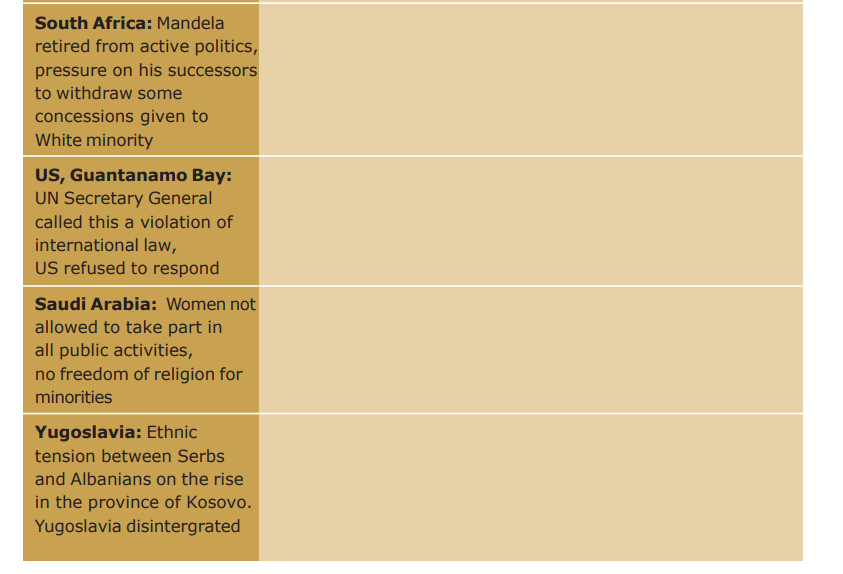

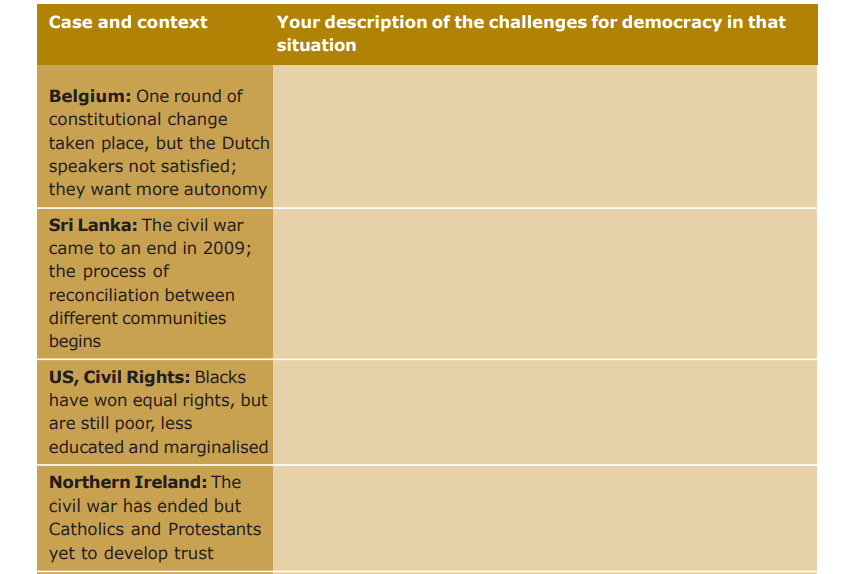

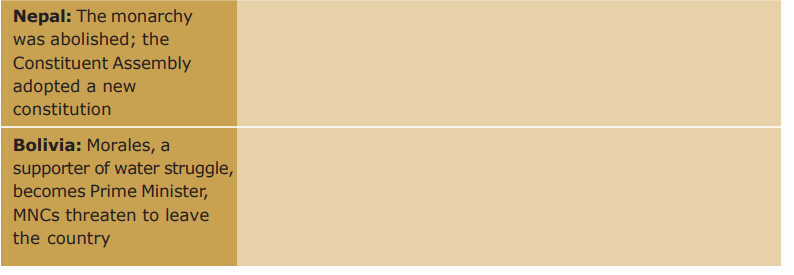

We have noted or hinted at these challenges in all the various examples and stories that we studied in our textbook of Class IX and in the earlier chapters of this book. Let us go back to all the major stops in our tour of democracy, refresh our memory and note down the challenges that democracy faces in each of these.

Different contexts, different challenges

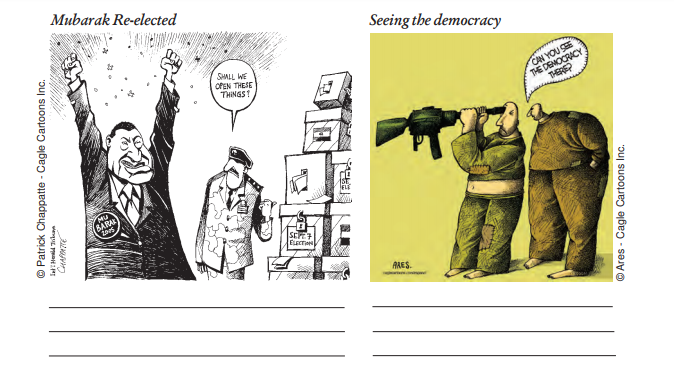

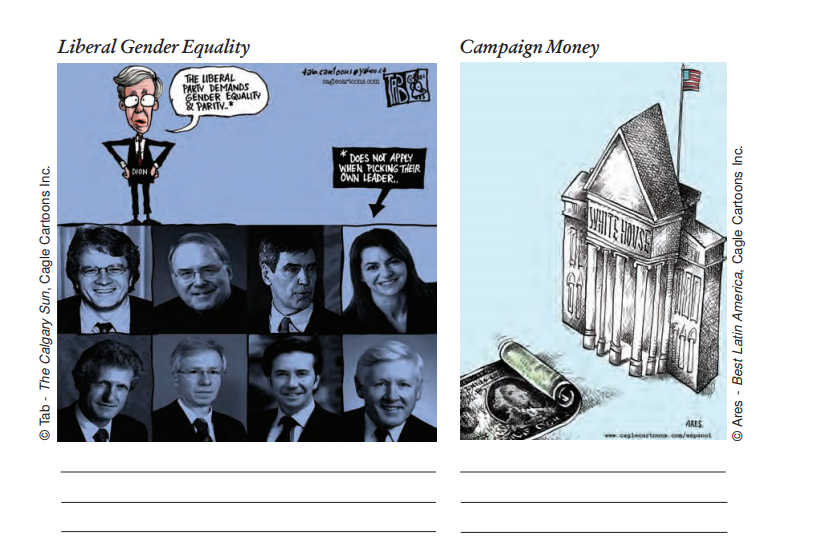

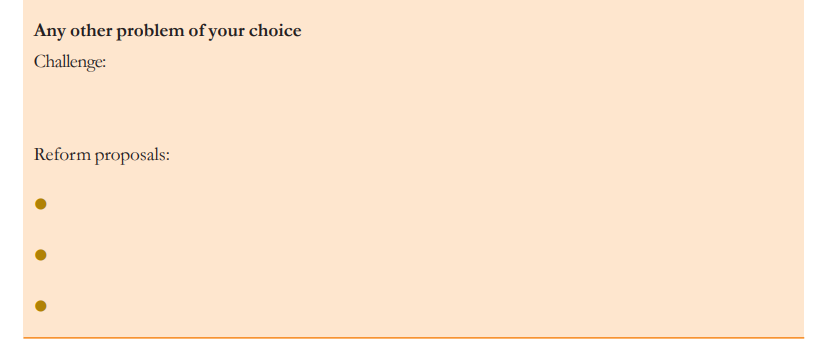

Each of these cartoons represents a challenge to democracy. Please describe what that challenge is. Also place it in one of the three categories mentioned in the first section.

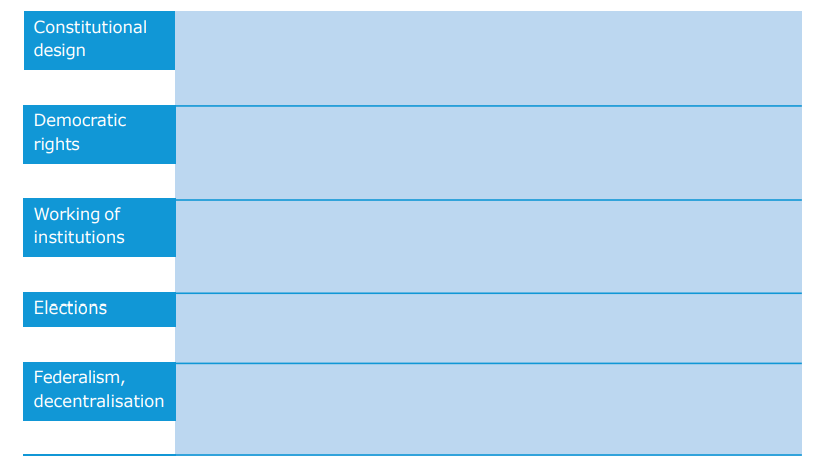

Different types of challenges

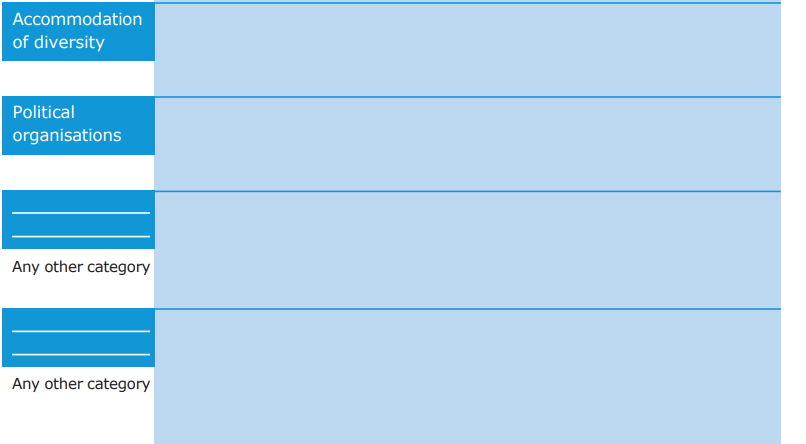

Now that you have noted down all these challenges, let us group these together into some broad categories. Given below are some spheres or sites of democratic politics. You may place against each of these the specific challenges that you noted for one or more countries or cartoons in the previous section. In addition to that write one item for India for each of these spheres. In case you find that some challenges do not fit into any of the categories given below, you can create new categories and put some items under that.

Let us group these again, this time by the nature of these challenges as per the classification suggested in the first section. For each of these categories, find at least one example from India as well.

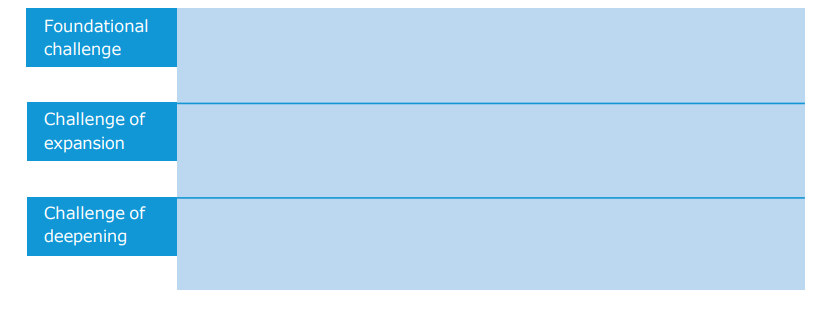

Now let us think only about India. Think of all the challenges that democracy faces in contemporary India. List those five that should be addressed first of all. The listing should be in order of priority, i.e, the challenge you find most important or pressing should be mentioned at number 1, and so on. Give one example of that challenge and your reasons for assigning it the priority.

Thinking about political reforms

Each of these challenges is linked to the possibility of reforms. As mentioned above, we discuss challenges only because we think these can be overcome. Generally all the suggestions or proposals about overcoming various challenges to democracy are called ‘democracy reform’ or ‘political reform’. We are not going to give here a list of desirable political reforms, for there cannot be any such list. If all the countries do not have the same challenges, it follows that everyone cannot follow the same recipe of political reforms. We cannot prescribe a procedure for car repair without knowing which model the car is, what the defect is and what tools are available, where the car has broken down, etc.

Can we at least have a list of such reforms for our country in today’s context? We can develop some proposals for reforms at the national level. But the real challenge of reforms may not lie at the national level. Some of the crucial questions need to be thought at the State or local level. Besides, such a list may become irrelevant after some time. So, instead of that let us think of some broad guidelines that can be kept in mind while devising ways and means for political reforms in India:

It is very tempting to think of legal ways of reforming politics, to think of new laws to ban undesirable things. But this temptation needs to be resisted. No doubt, law has an important role to play in political reform. Carefully devised changes in law can help to discourage wrong political practices and encourage good ones. But legal-constitutional changes by themselves cannot overcome challenges to democracy. This is like the rules of cricket. A change in rules for LBW decisions helped to reduce negative batting tactics. But no one would ever think that the quality of cricket could be improved mainly through changes in the rules. This is to be done mainly by the players, coaches and administrators. Similarly, democratic reforms are to be carried out mainly by political activists, parties, movements and politically conscious citizens.

Any legal change must carefully look at what results it will have on politics. Sometimes the results may be counter-productive. For example, many states have banned people who have more than two children from contesting panchayat elections. This has resulted in denial of democratic opportunity to many poor and women, which was not intended. Generally, laws that seek to ban something are not very successful in politics. Laws that give political actors incentives to do good things have more chances of working. The best laws are those which empower people to carry out democratic reforms. The Right to Information Act is a good example of a law that empowers the people to find out what is happening in government and act as watchdogs of democracy. Such a law helps to control corruption and supplements the existing laws that banned corruption and imposed strict penalties.

Democratic reforms are to be brought about principally through political practice. Therefore, the main focus of political reforms should be on ways to strengthen democratic practice. As we discussed in the chapter on political parties, the most important concern should be to increase and improve the quality of political participation by ordinary citizens.

Any proposal for political reforms should think not only about what is a good solution but also about who will implement it and how. It is not very wise to think that the legislatures will pass legislations that go against the interest of all the political parties and MPs. But measures that rely on democratic movements, citizens’ organisations and the media are likely to succeed.

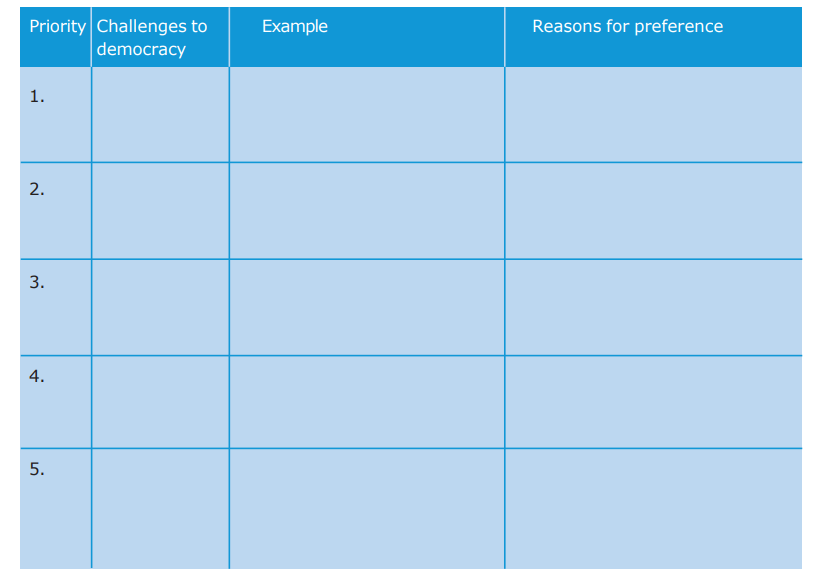

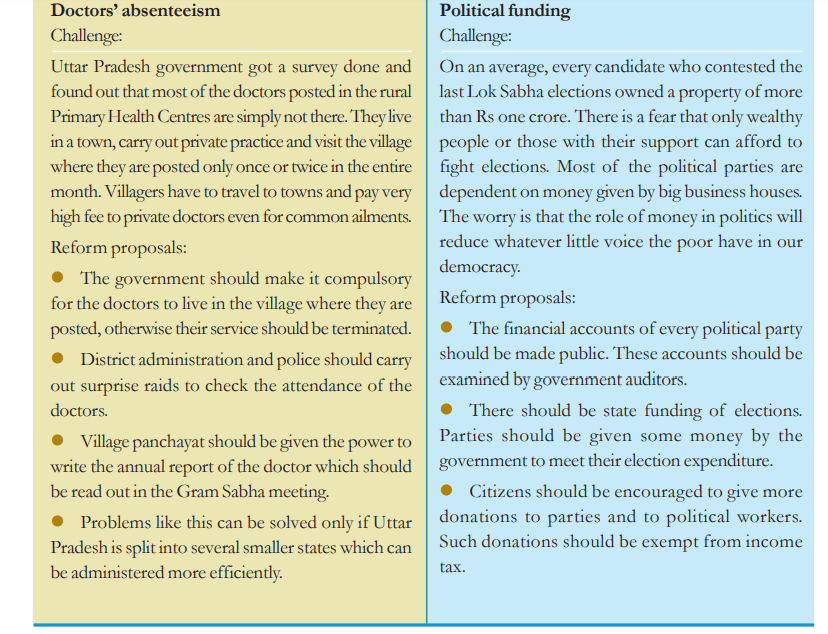

Let us keep these general guidelines in mind and look at some specific instances of challenges to democracy that require some measure of reform. Let us try to come up with some concrete proposals of reform.

Here are some challenges that require political reforms. Discuss these challenges in detail. Study the reform options offered here and give your preferred solution with reasons. Remember that none of the options offered here is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. You can opt for a mix of more than one options, or come up with something that is not offered here. But you must give your solution in detail and offer reasons for your choice.

Reforming politics

Rose managed to catch Madam Lyngdoh outside the classroom, something she had been planning to do for some time. “Ma’am! I really liked that Canadian cartoon”. Rose needed

something to open the conversation. “Which one?” Madam Lyngdoh could not recall. “Ma’am, the one which says 98% Canadians want all the politicians to be locked in the trunk of a car and thrown into Niagara falls. I was thinking of our politicians. We would need a bigger vehicle and a river as mighty as Brahmaputra!”

Lyngdoh Ma’am smiled at Rose. Like most Indians, she is also very much unhappy with the way politicians of the country have been behaving and running the parties and governments. But she wanted Rose to appreciate the complexity of the problem: “Do you think our problems will be solved if we get rid of our politicians?,” she asked.

“Yes, Ma’am. Aren’t these mean politicians responsible for all the problems in our country? I mean corruption, defection, casteism, communal violence, criminality… everything.”

Lyngdoh Madam: “So, all we need is to get rid of the current lot. Are you sure that those who replace them will not do these things?”

Rose: “Well, I had not thought of it, but may be not. May be we will get leaders of better character”.

Lyngdoh Madam: “I agree with you that the situation will change if people show more care and alertness to reject corrupt and bad politicians and elect the right ones. And, maybe, all politicians are not corrupt…”

“How can you say that Ma’am” interrupted Rose.

Lyngdoh Madam: “I did not say that politicians are not corrupt. Maybe when you think of politicians, you think of these big people whose photos appear in newspapers. I think of political leaders that I have known. I don’t think that the political leaders I know are more corrupt than my own colleagues, government officials, contractors or other middle class professionals that I know. The corruption of the politician is more visible and we get the impression that all politicians are corrupt. Some of them are and some of them are not.”

Rose did not give up. “Ma’am, what I meant is that there should be strict laws to curb corruption and wrong practices like appeals to caste and community.”

Lyngdoh Madam: “I am not sure, Rose. For one thing there is already a law banning any appeal to caste and religion in politics. Politicians find a way to bypass that. Laws can have little impact unless people resist attempts to mislead and divide people in the name of caste and religion. You cannot have democracy in a real sense unless people and politicians overcome the barriers of caste and religion.”

Redefining democracy

We began this tour of democracy last year with a minimal definition of democracy. Do you remember that? This is what Chapter 2 of your textbook said last year: democracy is a form of government in which the rulers are elected by the people. We then looked at many cases and expanded the definition slightly to add some qualifications:

the rulers elected by the people must take all the major decisions;

elections must offer a choice and fair opportunity to the people to change the current rulers;

this choice and opportunity should be available to all the people on an equal basis; and

the exercise of this choice must lead to a government limited by basic rules of the constitution and citizens’ rights.

You may have felt disappointed that the definition did not refer to any high ideals that we associate with democracy. But in operational terms, we deliberately started with a minimalist but clear definition of democracy. It allowed us to make a clear distinction between democratic and non-democratic regimes.

You may have noticed that in the course of our discussions of various aspects of democratic government and politics, we have gone beyond that definition:

We discussed democratic rights at length and noted that these rights are not limited to the right to vote, stand in elections and form political organisations. We discussed some social and economic rights that a democracy should offer to its citizens.

We have taken up power sharing as the spirit of democracy and discussed how power sharing between governments and social groups is necessary in

a democracy.

We saw how democracy cannot be the brute rule of majority and how a respect for minority voice is necessary for democracy.

Our discussion of democracy has gone beyond the government and its activities. We discussed how eliminating discrimination based on caste, religion and gender is important in a democracy.

Finally, we have had some discussion about some outcomes that one can expect from a democracy.

In doing so, we have not gone against the definition of democracy offered last year. We began then with a definition of what is the minimum a country must have to be called a democracy. In the course of our discussion we moved to the set of desirable conditions that a democracy should have. We have moved from the definition of democracy to the description of a good democracy.

Reading between the Lines

© Ares - Best Latin America, Cagle Cartoons Inc.

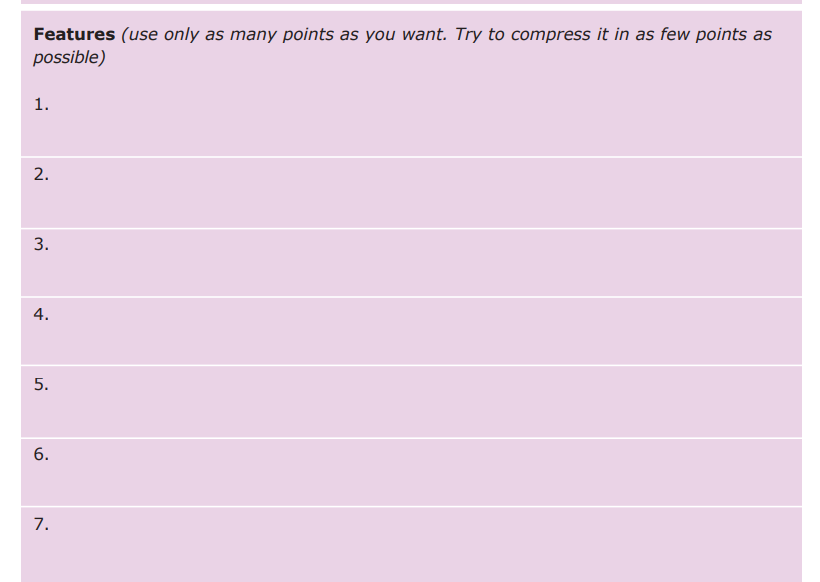

How do we define a good democracy? What are its features? Which are the features a democracy must have to be called a good democracy? And what must not take place in a democracy if it is a good democracy?

You decide that.

Here is your space for writing your own definition of good democracy.

(Write your name here) ________________________ ’s definition of good democracy (not more than 50 words):

How did you like this exercise? Was it enjoyable? Very demanding? A little frustrating? And a little scary? Are you a little resentful that the textbook did not help you in this crucial task? Are you worried that your definition may not be ‘correct’?

Here then is your last lesson in thinking about democracy: there is no fixed definition of good democracy. A good democracy is what we think it is and what we wish to make it. This may sound strange. Yet, think of it: is it democratic for someone to dictate to us what a good democracy is?