Table of Contents

2

INDIAN ECONOMY

1950-1990

After studying this chapter, the learners will

• come to know the goals of India’s five year plans

• know about the development policies in different sectors such as agriculture and industry from 1950-1990

• learn to think about the merits and limitations of a regulated economy.

The central objective of Planning in India... is to initiate a process of development which will raise the living standards and open out to the people new opportunities for a richer and more varied life. First Five Year Plan

2.1 INTRODUCTION

On 15 August 1947, India woke to a new dawn of freedom. Finally we were masters of our own destiny after some two hundred years of British rule; the job of nation building was now in our own hands. The leaders of independent India had to decide, among other things, the type of economic system most suitable for our nation, a system which would promote the welfare of all rather than a few. There are different types of economic systems (see Box 2.1) and among them, socialism appealed to Jawaharlal Nehru the most. However, he was not in favour of the kind of socialism established in the former Soviet Union where all the means of production, i.e. all the factories and farms in the country, were owned by the government. There was no private property. It is not possible in a democracy like India for the government to change the ownership pattern of land and other properties of its citizens in the way that it was done in the former Soviet Union.

Work These Out

Prepare a chart on the different types of economic systems prevalent in the world. List out the countries as capitalist, socialist and mixed economy.

Plan a class trip to an agriculture farm. Divide the class into seven groups with each group to plan a specific goal, for example, the purpose of the visit, money expenditure involved, time taken, resources, people accompanying the group and who need to be contacted, possible places of visit, possible questions to be asked etc. Now, with the help of your teacher, compile these specific goals and compare with long-term goals of successful visit to an agricultural farm.

Box 2.1: Types of Economic Systems

Every society has to answer three questions

What goods and services should be produced in the country?

How should the goods and services be produced? Should producers use more human labour or more capital (machines) for producing things?

How should the goods and services be distributed among people?

One answer to these questions is to depend on the market forces of supply and demand. In a market economy, also called capitalism, only those consumer goods will be produced that are in demand, i.e., goods that can be sold profitably either in the domestic or in the foreign markets. If cars are in demand, cars will be produced and if bicycles are in demand, bicycles will be produced. If labour is cheaper than capital, more labour-intensive methods of production will be used and vice-versa. In a capitalist society the goods produced are distributed among people not on the basis of what people need but on the basis of Purchasing Power—the ability to buy goods and services. That is, one has to have the money in the pocket to buy it. Low cost housing for the poor is much needed but will not count as demand in the market sense because the poor do not have the purchasing power to back the demand. As a result this commodity will not be produced and supplied as per market forces. Such a society did not appeal to Jawaharlal Nehru, our first prime minister, for it meant that the great majority of people of the country would be left behind without the chance to improve their quality of life.

A socialist society answers the three questions in a totally different manner. In a socialist society the government decides what goods are to be produced in accordance with the needs of society. It is assumed that the government knows what is good for the people of the country and so the desires of individual consumers are not given much importance. The government decides how goods are to be produced and how they should be distributed. In principle, distribution under socialism is supposed to be based on what people need and not on what they can afford to purchase. Unlike under capitalism, for example, a socialist nation provides free health care to all its citizens. Strictly, a socialist society has no private property since everything is owned by the state. In Cuba and China, for example, most of the economic activities are governed by the socialistic principles.

Most economies are mixed economies, i.e. the government and the market together answer the three questions of what to produce, how to produce and how to distribute what is produced. In a mixed economy, the market will provide whatever goods and services it can produce well, and the government will provide essential goods and services which the market fails to do.

Nehru, and many other leaders and thinkers of the newly independent India, sought an alternative to the extreme versions of capitalism and socialism. Basically sympathising with the socialist outlook, they found the answer in an economic system which, in their view, combined the best features of socialism without its drawbacks. In this view, India would be a socialist society with a strong public sector but also with private property and democracy; the government would plan (see Box 2.2) for the economy with the private sector being encouraged to be part of the plan effort. The ‘Industrial Policy Resolution’ of 1948 and the Directive Principles of the Indian Constitution reflected

this outlook. In 1950, the Planning Commission was set up with the Prime Minister as its Chairperson. The era of five year plans had begun.

Box 2.2: What is a Plan?

A plan spells out how the resources of a nation should be put to use. It should have some general goals as well as specific objectives which are to be achieved within a specified period of time; in India plans are of five years duration and are called five year plans (we borrowed this from the former Soviet Union, the pioneer in national planning). Our plan documents not only specify the objectives to be attained in the five years of a plan but also what is to be achieved over a period of twenty years. This long-term plan is called ‘perspective plan’. The five year plans are supposed to provide the basis for the perspective plan.

It will be unrealistic to expect all the goals of a plan to be given equal importance in all the plans. In fact the goals may actually be in conflict. For example, the goal of introducing modern technology may be in conflict with the goal of increasing employment if the technology reduces the need for labour. The planners have to balance the goals, a very difficult job indeed. We find different goals being emphasised in different plans in India.

Our five year plans do not spell out how much of each and every good and service is to be produced. This is neither possible nor necessary (the former Soviet Union tried to do this and failed). It is enough if the plan is specific about the sectors where it plays a commanding role, for instance, power generation and irrigation, while leaving the rest to the market.

2.2 The Goals of Five Year Plans

A plan should have some clearly specified goals. The goals of the five year plans are: growth, modernisation, self-reliance and equity. This does not mean that all the plans have given equal importance to all these goals. Due to limited resources, a choice has to be made in each plan about which of the goals is to be given primary importance. Nevertheless, the planners have to ensure that, as far as possible, the policies of the plans do not contradict these four goals. Let us now learn about the goals of planning in some detail.

Growth: It refers to increase in the country’s capacity to produce the output of goods and services within the country. It implies either a larger stock of productive capital, or a larger size of supporting services like transport and banking, or an increase in the efficiency of productive capital and services. A good indicator of economic growth, in the language of

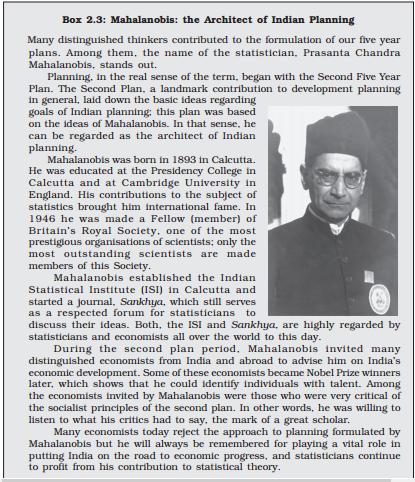

Source: Sukhamoy Chakravarty, ‘Mahalanobis, Prasanta Chandra’ in John Eatwell et.al, (Eds.) The New Palgrave Dictionary: Economic Development, W.W. Norton, New York and London.

economics, is steady increase in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The GDP is the market value of all the goods and services produced in the country during a year. You can think of the GDP as a cake and growth is increase in the size of the cake. If the cake is larger, more people can enjoy it. It is necessary to produce more goods and services if the people of India are to enjoy (in the words of the First Five Year Plan) a more rich and varied life.

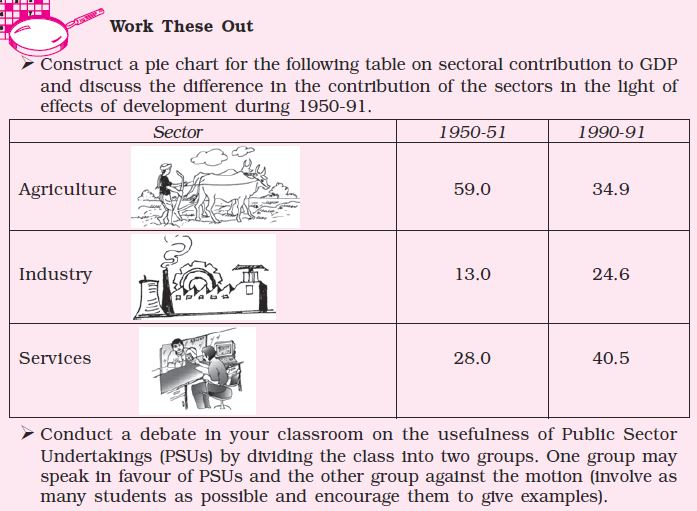

The GDP of a country is derived from the different sectors of the economy, namely the agricultural sector, the industrial sector and the service sector. The contribution made by each of these sectors makes up the structural composition of the economy. In some countries, growth in agriculture contributes more to the GDP growth, while in some countries the growth in the service sector contributes more to GDP growth (see Box 2.4).

Modernisation: To increase the production of goods and services

the producers have to adopt new technology. For example, a farmer can increase the output on the farm by using new seed varieties instead of using the old ones. Similarly, a factory can increase output by using a new type of machine. Adoption of new technology is called modernisation.

However, modernisation does not refer only to the use of new technology but also to changes in social outlook such as the recognition that women should have the same rights as men. In a traditional society, women are supposed to remain at home while men work. A modern society makes use of the talents of women in the work place — in banks, factories, schools etc. — and such a society in most occassions is also prosperous.

Box 2.4: The Service Sector

As a country develops, it undergoes ‘structural change’. In the case of India, the structural change is peculiar. Usually, with development, the share of agriculture declines and the share of industry becomes dominant. At higher levels of development, the service sector contributes more to the GDP than the other two sectors. In India, the share of agriculture in the GDP was more than 50 per cent—as we would expect for a poor country. But by 1990 the share of the service sector was 40.59 per cent, more than that of agriculture or industry, like what we find in developed nations. This phenomenon of growing share of the service sector was accelerated in the post 1991 period (this marked the onset of globalisation in the country which will be discussed in a subsequent chapter).

Self-reliance: A nation can promote economic growth and modernisation by using its own resources or by using resources imported from other nations. The first seven five year plans gave importance to self-reliance which means avoiding imports

of those goods which could be produced in India itself. This policy was considered a necessity in order to reduce our dependence on foreign countries, especially for food. It is understandable that people who were recently freed from foreign domination should give importance to self-reliance. Further, it was feared that dependence on imported food supplies, foreign technology and foreign capital may make India’s sovereignty vulnerable to foreign interference in our policies.

Equity: Now growth, modernisation and self-reliance, by themselves, may not improve the kind of life which people are living. A country can have high growth, the most modern technology developed in the country itself, and also have most of its people living in poverty. It is important to ensure that the benefits of economic prosperity reach the poor sections as well instead of being enjoyed only by the rich. So, in addition to growth, modernisation and self-reliance, equity is also important. Every Indian should be able to meet his or her basic needs such as food, a decent house, education and health care and inequality in the distribution of wealth should be reduced.

Work These Out

Discuss in your class the changes in technology used for

(a) Production of food grains

(b) Packaging of products

(c) Mass communication

Find out and prepare a list of major items that India imported and exported during 1990-91 and 2014-15.

(a) Observe the difference

(b) Do you see the impact of self-reliance? Discuss.

For getting these details you may refer to Economic Survey of the latest year.

Let us now see how the first seven five year plans, covering the period 1950-1990, attempted to attain these four goals and the extent to which they succeeded in doing so, with reference to agriculture, industry and trade. You will study the policies and developmental issues taken up after 1991 in Chapter 3.

2.3 Agriculture

You have learnt in Chapter 1 that during the colonial rule there was neither growth nor equity in the agricultural sector. The policy makers of independent India had to address these issues which they did through land reforms and promoting the use of ‘High Yielding Variety’ (HYV) seeds which ushered in a revolution in Indian agriculture.

Land Reforms: At the time of independence, the land tenure system was characterised by intermediaries (variously called zamindars, jagirdars etc.) who merely collected rent from the actual tillers of the soil without contributing towards improvements on the farm. The low productivity of the agricultural sector forced India to import food from the United States of America (U.S.A.). Equity in agriculture called for land reforms which primarily refer to change in the ownership of landholdings. Just a year after independence, steps were taken to abolish intermediaries and to make the tillers the owners of land. The idea behind this move was that ownership of land would give incentives (see Box 2.5) to the tillers to invest in making improvements provided sufficient capital was made available to them. Land ceiling was another policy to promote equity in the agricultural sector. This means fixing the maximum size of land which could be owned by an individual. The purpose of land ceiling was to reduce the concentration of land ownership in a few hands.

The abolition of intermediaries meant that some 200 lakh tenants came into direct contact with the government — they were thus

freed from being exploited by the zamindars. The ownership conferred on tenants gave them the incentive to increase output and this contributed to growth in agriculture. However, the goal of equity was not fully served

by abolition of intermediaries. In some areas the former zamindars continued to own large areas of land by making use of some loopholes in the legislation; there were cases where tenants were evicted and the landowners claimed to be self-cultivators (the actual tillers), claiming ownership of the land; and even when the tillers got ownership of land, the poorest of the agricultural labourers (such as sharecroppers and landless labourers) did not benefit from land reforms.

Box 2.5: Ownership and Incentives

The policy of ‘land to the tiller’ is based on the idea that the cultivators will take more interest—they will have more incentive—in increasing output if they are the owners of the land. This is because ownership of land enables the tiller to make profit from the increased output. Tenants do not have the incentive to make improvements on land since it is the landowner who would benefit more from higher output. The importance of ownership in providing incentives is well illustrated by the carelessness with which farmers in the former Soviet Union used to pack fruits for sale. It was not uncommon to see farmers packing rotten fruits along with fresh fruits in the same box. Now, every farmer knows that the rotten fruits will spoil the fresh fruits if they are packed together. This will be a loss to the farmer since the fruits cannot be sold. So why did the Soviet farmers do something which would so obviously result in loss for them? The answer lies in the incentives facing the farmers. Since farmers in the former Soviet Union did not own any land, they neither enjoyed the profits nor suffered the losses. In the absence of ownership, there was no incentive on the part of farmers to be efficient, which also explains the poor performance of the agricultural sector in the Soviet Union despite availability of vast areas of highly fertile land.

Source: Thomas Sowell, Basic Economics: A Citizen’s Guide to the Economy, New York: Basic Books, 2004, Second Edition.

The land ceiling legislation also faced hurdles. The big landlords challenged the legislation in the courts, delaying its implementation. They used this delay to register their lands in the name of close relatives, thereby escaping from the legislation. The legislation also had a lot of loopholes which were exploited by the big landholders to retain their land. Land reforms were successful in Kerala and West Bengal because these states had governments committed to the policy of land to the tiller. Unfortunately other states did not have the same level of commitment and vast inequality in landholding continues to this day.

The Green Revolution: At independence, about 75 per cent of the country’s population was dependent on agriculture. Productivity in the agricultural sector was very low because of the use of old technology and the absence of required infrastructure for the vast majority of farmers. India’s agriculture vitally depends on the monsoon and if the monsoon fell short the farmers were in trouble unless they had access to irrigation facilities which very few had. The stagnation in agriculture during the colonial rule was permanently broken by the green revolution. This refers to the large increase in production of food grains resulting from the use of high yielding variety (HYV) seeds especially for wheat and rice. The use of these seeds required the use of fertiliser and pesticide in the correct quantities as well as regular supply of water; the application of these inputs in correct proportions is vital. The farmers who could benefit from HYV seeds required reliable irrigation facilities as well as the financial resources to purchase fertiliser and pesticide. As a result, in the first phase of the green revolution (approximately mid 1960s upto mid 1970s), the use of HYV seeds was restricted to the more affluent states such as Punjab, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Further, the use of HYV seeds primarily benefited the wheat-growing regions only. In the second phase of the green revolution

(mid-1970s to mid-1980s), the HYV technology spread to a larger number of states and benefited more variety of crops. The spread of green revolution technology enabled India to achieve self-sufficiency in food grains; we no longer had to be at the mercy of America, or any other nation, for meeting our nation’s food requirements.

Growth in agricultural output is important but it is not enough. If a large proportion of this increase is consumed by the farmers themselves instead of being sold in the market, the higher output will not make much of a difference to the economy as a whole. If, on the other hand, a substantial amount of agricultural produce is sold in the market by the farmers, the higher output can make a difference to the economy. The portion of agricultural produce which is sold in the market by the farmers is called marketed surplus. A good proportion of the rice and wheat produced during the green revolution period (available as marketed surplus) was sold by the farmers in the market. As a result, the price of food grains declined relative to other items of consumption. The low-income groups, who spend a large percentage of their income on food, benefited from this decline in relative prices. The green revolution enabled the government to procure sufficient amount of food grains to build a stock which could be used in times of food shortage.

While the nation had immensely benefited from the green revolution, the technology involved was not free from risks. One such risk was the possibility that it would increase the disparities between small and big farmers—since only the big farmers could afford the required inputs, thereby reaping most of the benefits of the green revolution. Moreover, the HYV crops were also more prone to attack by pests and the small farmers who adopted this technology could lose everything in a pest attack.

Fortunately, these fears did not come true because of the steps taken by the government. The government provided loans at a low interest rate to small farmers and subsidised fertilisers so that small farmers could also have access to the needed inputs. Since the small farmers could obtain the required inputs, the output on small farms equalled the output on large farms in the course of time. As a result, the green revolution benefited the small as well as rich farmers. The risk of the small farmers being ruined when pests attack their crops was considerably reduced by the services rendered by research institutes established by the government. You should note that the green revolution would have favoured the rich farmers only if the state did not play an extensive role in ensuring that the small farmer also gains from the new technology.

The Debate Over Subsidies: The economic justification of subsidies in agriculture is, at present, a hotly debated question. It is generally agreed that it was necessary to use subsidies to provide an incentive for adoption of the new HYV technology by farmers in general and small farmers in particular. Any new technology will be looked upon as being risky by farmers. Subsidies were, therefore, needed to encourage farmers to test the new technology. Some economists believe that once the technology is found profitable and is widely adopted, subsidies should be phased out since their purpose has been served. Further, subsidies are meant to benefit the farmers but a substantial amount of fertiliser subsidy also benefits the fertiliser industry; and among farmers, the subsidy largely benefits the farmers in the more prosperous regions. Therefore, it is argued that there is no case for continuing with fertiliser subsidies; it does not benefit the target group and it is a huge burden on the government’s finances (see also Box 2.6).

On the other hand, some believe that the government should continue with agricultural subsidies because farming in India continues to be a risky business. Most farmers are very poor and they will not be able to afford the required inputs without subsidies. Eliminating subsidies will increase the inequality between rich and poor farmers and violate the goal of equity. These experts argue that if subsidies are largely benefiting the fertiliser industry and big farmers, the correct policy is not to abolish subsidies but to take steps to ensure that only the poor farmers enjoy the benefits.

Box 2.6: Prices as Signals

You would have learnt in an earlier class about how prices of goods are determined in the market. It is important to understand that prices are signals about the availability of goods. If a good becomes scarce, its price will rise and those who use this good will have the incentive to make efficient decisions about its use based on the price. If the price of water goes up because of lower supply, people will have the incentive to use it with greater care; for example, they may stop watering the garden to conserve water. We complain whenever the price of petrol increases and blame it on the government. But the increase in petrol price reflects greater scarcity and the price rise is a signal that less petrol is available—this provides an incentive to use less petrol or look for alternate fuels.

Some economists point out that subsidies do not allow prices to indicate the supply of a good. When electricity and water are provided at a subsidised rate or free, they will be used wastefully without any concern for their scarcity. Farmers will cultivate water intensive crops if water is supplied free, although the water resources in that region may be scarce and such crops will further deplete the already scarce resources. If water is priced to reflect scarcity, farmers will cultivate crops suitable to the region. Fertiliser and pesticide subsidies result in overuse of resources which can be harmful to the environment. Subsidies provide an incentive for wasteful use of resources. Think about subsidies in terms of incentives and ask yourself whether it is wise from the economic viewpoint to provide free electricity to farmers.

Thus, by the late 1960s, Indian agricultural productivity had increased sufficiently to enable the country to be self-sufficient in food grains. This is an achievement to be proud of. On the negative side, some 65 per cent of the country’s population continued to be employed in agriculture even as late as 1990. Economists have found that as a nation becomes more prosperous, the proportion of GDP contributed by agriculture as well as the proportion of population working in the sector declines considerably. In India, between 1950 and 1990, the proportion of GDP contributed by agriculture declined significantly but not the population depending on it (67.5 per cent in 1950 to 64.9 per cent by 1990). Why was such a large proportion of the population engaged in agriculture although agricultural output could have grown with much less people working in the sector? The answer is that the industrial sector and the service sector did not absorb the people working in the agricultural sector. Many economists call this an important failure of our policies followed during 1950-1990.

2.4 Industry and Trade

Economists have found that poor nations can progress only if they have a good industrial sector. Industry provides employment which is more stable than the employment in agriculture; it promotes modernisation and overall prosperity. It is for this reason that the five year plans place a lot of emphasis on industrial development. You might have studied in the previous chapter that, at the time of independence, the variety of industries was very narrow — largely confined to cotton textiles and jute. There were two well-managed iron and steel firms — one in Jamshedpur and the other in Kolkata — but, obviously, we needed to expand the industrial base with a variety of industries if the economy was to grow.

Work These Out

Ø A group of students may visit an agricultural farm, prepare a case study on the method of farming used, that is, types of seeds, fertilisers, machines, means of irrigation, cost involved, marketable surplus and income earned.

It will be beneficial if the changes in cultivation methods could be collected from an elderly member of the farming family

(a) Discuss the findings in your class.

(b) The different groups can then prepare a chart showing variations in cost of production, productivity, use of seeds, fertilisers, means of irrigation, time taken, marketable surplus and income of the family.

Ø Collect newspaper cuttings related to the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organisation (and meets of G7, G8, G10 countries). Discuss the views shared by the developed and developing countries on farm subsidies.

Ø Prepare pie charts on the occupational structure of the Indian economy available in the following table.

Sector 1950–51 1990–91

Agriculture 72.1 66.8

Industry 10.7 12.7

Services 17.2 20.5

ØStudy the arguments for and against agricultural subsidies. What is your view on this issue?

ØSome economists argue that farmers in other countries, particularly developed countries, are provided with high amount of subsidies and are encouraged to export their produce to other countries. Do you think our farmers will be able to compete with farmers from developed countries? Discuss.

Public and Private Sectors in Indian Industrial Development: The big question facing the policy makers was — what should be the role of the government and the private sector in industrial development? At the time of independence, Indian industrialists did not have the capital to undertake investment in industrial ventures required for the development of our economy; nor was the market big enough to encourage industrialists to undertake major projects even if they had the capital to do so. It is principally for these reasons that the state had to play an extensive role in promoting the industrial sector. In addition, the decision to develop the Indian economy on socialist lines led to the policy of the state controlling the commanding heights of the economy, as the Second Five Year plan put it. This meant that the state would have complete control of those industries that were vital for the economy. The policies of the private sector would have to be complimentary to those of the public sector, with the public sector leading the way.

Industrial Policy Resolution 1956 (IPR 1956): In accordance with the goal of the state controlling the commanding heights of the economy, the Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956 was adopted. This resolution formed the basis of the Second Five Year Plan, the plan which tried to build the basis for a socialist pattern of society. This resolution classified industries into three categories. The first category comprised industries which would be exclusively owned by the state; the second category consisted of industries in which the private sector could supplement the efforts of the state sector, with the state taking the sole responsibility for starting new units; the third category consisted of the remaining industries which were to be in the private sector.

Although there was a category of industries left to the private sector, the sector was kept under state control through a system of licenses. No new industry was allowed unless a license was obtained from the government. This policy was used for promoting industry in backward regions; it was easier to obtain a license if the industrial unit was established in an economically backward area. In addition, such units were given certain concessions such as tax benefits and electricity at a lower tariff. The purpose of this policy was to promote regional equality.

Even an existing industry had to obtain a license for expanding output or for diversifying production (producing a new variety of goods). This was meant to ensure that the quantity of goods produced was not more than what the economy required. License to expand production was given only if the government was convinced that the economy required a larger quantity of goods.

Small-Scale Industry: In 1955, the Village and Small-Scale Industries Committee, also called the Karve Committee, noted the possibility of using small-scale industries for promoting rural development. A ‘small-scale industry’ is defined with reference to the maximum investment allowed on the assets of a unit. This limit has changed over a period of time. In 1950 a small-scale industrial unit was one which invested a maximum of rupees five lakh; at present the maximum investment allowed is rupees one crore.

It is believed that small-scale industries are more ‘labour intensive’ i.e., they use more labour than the large-scale industries and, therefore, generate more employment. But these industries cannot compete with the big industrial firms; it is obvious that development of small-scale industry requires them to be shielded from the large firms. For this purpose, the production of a number of products was reserved for the small-scale industry; the criterion of reservation being the ability of these units to manufacture the goods. They were also given concessions such as lower excise duty and bank loans at lower interest rates.

2.5 TRADE POLICY: IMPORT SUBSTITUTION

The industrial policy that we adopted was closely related to the trade policy. In the first seven plans, trade was characterised by what is commonly called an inward looking trade strategy. Technically, this strategy is called import substitution. This policy aimed at replacing or substituting imports with domestic production. For example, instead of importing vehicles made in a foreign country, industries would be encouraged to produce them in India itself. In this policy the government protected the domestic industries from foreign competition. Protection from imports took two forms: tariffs and quotas. Tariffs are a tax on imported goods; they make imported goods more expensive and discourage their use. Quotas specify the quantity of goods which can be imported. The effect of tariffs and quotas is that they restrict imports and, therefore, protect the domestic firms from foreign competition.

The policy of protection is based on the notion that industries of developing countries are not in a position to compete against the goods produced by more developed economies. It is assumed that if the domestic industries are protected they will learn to compete in the course of time. Our planners also feared the possibility of foreign exchange being spent on import of luxury goods if no restrictions were placed on imports. Nor was any serious thought given to promote exports until the mid-1980s.

Effect of Policies on Industrial Development: The achievements of India’s industrial sector during the first seven plans are impressive indeed. The proportion of GDP contributed by the industrial sector increased in the period from 11.8 per cent in 1950-51 to 24.6 per cent in 1990-91. The rise in the industry’s share of GDP is an important indicator of development. The six per cent annual growth rate of the industrial sector during the period is commendable. No longer was Indian industry restricted largely to cotton textiles and jute; in fact, the industrial sector became well diversified by 1990, largely due to

the public sector. The promotion of small-scale industries gave opportunities to those people who did not have the capital to start large firms to get into business. Protection from foreign competition enabled the development of indigenous industries in the areas of electronics and automobile sectors which otherwise could not have developed.

In spite of the contribution made by the public sector to the growth of the Indian economy, some economists are critical of the performance of many public sector enterprises. It was proposed at the beginning of this chapter that initially public sector was required in a big way. It is now widely held that state enterprises continued to produce certain goods and services (often monopolising them) although this was no longer required. An example is the provision of telecommunication service. This industry continued to be reserved for the Public Sector even after it was realised that private sector firms could also provide it. Due to the absence of competition, even till the late 1990s, one had to wait for a long time to get a telephone connection. Another instance could be the establishment of Modern Bread, a bread-manufacturing firm, as if the private sector could not manufacture bread! In 2001 this firm was sold to the private sector. The point is that after four decades of Planned development of Indian Economy no distinction was made between (i) what the public sector alone can do and (ii) what the private sector can also do. For example, even now only the public sector supplies national defense. And even though the private sector can manage hotels well, yet, the government also runs hotels. This has led some scholars to argue that the state should get out of areas which the private sector can manage and the government may concentrate its resources on important services which the private sector cannot provide.

Many public sector firms incurred huge losses but continued to function because it is difficult to close a government undertaking even if it is a drain on the nation’s limited resources. This does not mean that private firms are always profitable (indeed, quite a few of the public sector firms were originally private firms which were on the verge of closure due to losses; they were then nationalised to protect the jobs of the workers). However, a loss-making private firm will not waste resources by being kept running despite the losses.

The need to obtain a license to start an industry was misused by industrial houses; a big industrialist would get a license not for starting a new firm but to prevent competitors from starting new firms. The excessive regulation of what came to be called the permit license raj prevented certain firms from becoming more efficient. More time was spent by industrialists in trying to obtain a license or lobby with the concerned ministries rather than on thinking about how to improve their products.

The protection from foreign competition is also being criticised on the ground that it continued even after it proved to do more harm than good. Due to restrictions on imports, the Indian consumers had to purchase whatever the Indian producers produced. The producers were aware that they had a captive market; so they had no incentive to improve the quality of their goods. Why should they think of improving quality when they could sell low quality items at a high price? Competition from imports forces our producers to be more efficient.

A few economists also point out that the public sector is not meant for earning profits but to promote the welfare of the nation. The public sector firms, on this view, should be evaluated on the basis of the extent to which they contribute to the welfare of people and not on the profits they earn. Regarding protection, some economists hold that we should protect our producers from foreign competition as long as the rich nations continue to do so. Owing to all these conflicts, economists called for a change in our policy. This, alongwith other problems, led the government to introduce a new economic policy in 1991.

2.6 Conclusion

The progress of the Indian economy during the first seven plans was impressive indeed. Our industries became far more diversified compared to the situation at independence. India became self- sufficient in food production thanks to the green revolution. Land reforms resulted in abolition of the hated zamindari system. However, many economists became dissatisfied with the performance of many public sector enterprises. Excessive government regulation prevented growth of entrepreneurship. In the name of self-reliance, our producers were protected against foreign competition and this did not give them the incentive to improve the quality of goods that they produced. Our policies were ‘inward oriented’ and so we failed to develop a strong export sector. The need for reform of economic policy was widely felt in the context of changing global economic scenario, and the new economic policy was initiated in 1991 to make our economy more efficient. This is the subject of the next chapter.

Recap

After independence, India envisaged an economic system which combines the best features of socialism and capitalism—this culminated in the mixed economy model.

All the economic planning has been formulated through five year plans.

Common goals of five year plans are growth, modernisation, self-sufficiency and equity.

The major policy initiatives in agriculture sector were land reforms and green revolution. These initiatives helped India to become self-sufficient in food grains production.

The proportion of people depending on agriculture did not decline as expected.

Policy initiatives in the industrial sector raised its contribution to GDP.

One of the major drawbacks in the industrial sector was the inefficient functioning of the public sector as it started incurring losses leading to drain on the nation’s limited resources.

EXERCISES

1. Define a plan.

2. Why did India opt for planning?

3. Why should plans have goals?

4. What are High Yielding Variety (HYV) seeds?

5. What is marketable surplus?

6. Explain the need and type of land reforms implemented in the agriculture sector.

7. What is Green Revolution? Why was it implemented and how did it benefit the farmers? Explain in brief.

8. Explain ‘growth with equity’ as a planning objective.

9. Does modernisation as a planning objective create contradiction in the light of employment generation? Explain.

10. Why was it necessary for a developing country like India to follow self-reliance as a planning objective?

11. What is sectoral composition of an economy? Is it necessary that the service sector should contribute maximum to GDP of an economy? Comment.

12. Why was public sector given a leading role in industrial development during the planning period?

13. Explain the statement that green revolution enabled the government to procure sufficient food grains to build its stocks that could be used during times of shortage.

14. While subsidies encourage farmers to use new technology, they are a huge burden on government finances. Discuss the usefulness of subsidies in the light of this fact.

15. Why, despite the implementation of green revolution, 65 per cent of our population continued to be engaged in the agriculture sector till 1990?

16. Though public sector is very essential for industries, many public sector undertakings incur huge losses and are a drain on the economy’s resources. Discuss the usefulness of public sector undertakings in the light of this fact.

17. Explain how import substitution can protect domestic industry.

18. Why and how was private sector regulated under the IPR 1956?

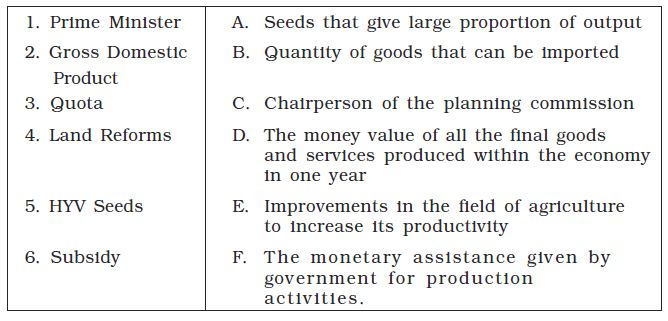

19. Match the following:

REFERENCES

Bhagwati, J. 1993. India in Transition: Freeing the Economy. Oxford University Press, Delhi.

Dandekar, V.M. 2004. Forty Years After Independence, in Bimal Jalan, (Ed.). The Indian Economy: Problems and Prospects.Penguin, Delhi.

Joshi, Vijay. and I.M.D. Little. 1996. India’s Economic Reforms 1991-2001. Oxford University Press, Delhi.

Mohan, Rakesh. 2004. Industrial Policy and Controls, in Bimal Jalan (Ed.). The Indian Economy: Problems and Prospects.Penguin, Delhi.

Rao, C.H. Hanumantha. 2004. Agriculture: Policy and Performance, in Bimal Jalan, (Ed.). The Indian Economy: Problems and Prospects. Penguin, Delhi.