Table of Contents

4

POVERTY

After studying this chapter, the learners will

• understand the various attributes of poverty

• comprehend the diverse dimensions relating to the concept of poverty

• critically appreciate the way poverty is estimated

• appreciate and be able to assess existing poverty alleviation programmes.

No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable.

Adam Smith

4.1 Introduction

In previous chapters, you have studied the economic policies that India has taken in the last seven decades and the outcome of these policies with relation to the various developmental indicators. Providing minimum basic needs to the people and reduction of poverty have been the major aims of independent India. The pattern of development that the successive five year plans envisaged laid emphasis on the upliftment of the poorest of the poor (Antyodaya), integrating the poor into the mainstream and achieving a minimum standard of living for all.

While addressing the Constituent Assembly in 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru had said, “This achievement (Independence) is but a step, an opening of opportunity, to the great triumphs and achievements that await us… the ending of poverty and ignorance and disease and inequality of opportunity”.

However, we need to know where we stand today. Poverty is not only a challenge for India, as more than one-fifth of the world’s poor live in India alone; but also for the world, where about 300 million people are not able to meet their basic needs.

Poverty has many faces, which have been changing from place to place and across time, and has been described in many ways. Most often, poverty is a situation that people want to escape. So, poverty is a call to action — for the poor and the wealthy alike — a call to change the world so that many more may have enough to eat, adequate shelter, access to education and health, protection from violence, and a voice in what happens in their communities.

To know what helps to reduce poverty, what works and what does not, what changes over time, poverty has to be defined, measured and studied — and even experienced. As poverty has many dimensions, it has to be looked at through a variety of indicators — levels of income and consumption, social indicators, and indicators of vulnerability to risks and of socio-political access.

4.2 Who are the Poor?

You would have noticed that in all localities and neighbourhoods, both in rural and urban areas, there are some of us who are poor and some who are rich. Read the story of Anu and Sudha. Their lives are examples of the two extremes (see Box 4.1). There are also people who belong to the many stages in between.

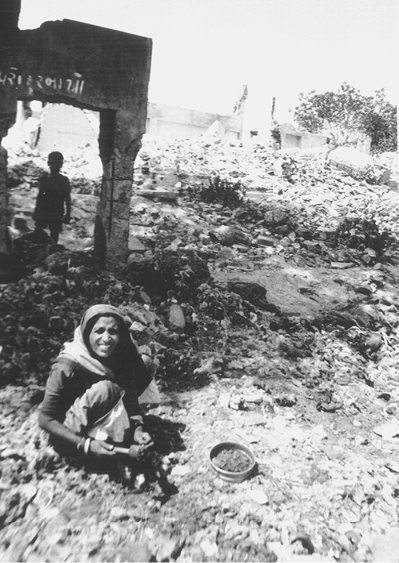

Push-cart vendors, street cobblers, women who string flowers, rag pickers, vendors and beggars are some examples of poor and vulnerable groups in urban areas. The poor people possess few assets and reside in kutcha hutments with walls made of baked mud and roofs made of grass, thatch, bamboo and wood. The poorest of them do not even have such dwellings. In rural areas many of them are landless. Even if some of them possess land, it is only dry or waste land. Many do not get to have even two meals a day. Starvation and hunger are the key features of the poorest households. The poor lack basic literacy and skills and hence have very limited economic opportunities. Poor people also face unstable employment.

Malnutrition is alarmingly high among the poor. Ill health, disability or serious illness makes them physically weak. They borrow from moneylenders, who charge high rates of interest that

lead them into chronic indebtedness. The poor are highly vulnerable. They are not able to negotiate their legal wages from employers and are exploited. Most poor households have no access to electricity. Their primary cooking fuel is firewood and cow dung cake. A large section of poor people do not even have access to safe drinking water. There is evidence of extreme gender inequality in the participation of gainful employment, education and in decision-making within the family. Poor women receive less care on their way to motherhood. Their children are less likely to survive or be born healthy.

Fig. 4.2 Many poor families live in kutcha houses

Economists identify the poor on the basis of their occupation and ownership of assets. They state

that the rural poor work mainly

as landless agricultural labourers, cultivators with very small landholdings, or landless labourers, who are engaged in a variety of

non-agricultural jobs and tenant cultivators with small land holdings. The urban poor are largely the overflow of the rural poor who had migrated to urban areas in search of alternative employment and livelihood, labourers who do a variety of casual jobs and the self-emloyed who sell a variety of things on roadsides and are engaged in various activities.

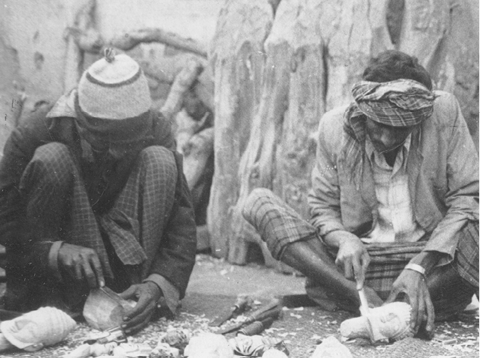

Fig. 4.1 Majority of agricultural labourers are poor

4.3 How are Poor People Identified?

If India is to solve the problem of poverty, it has to find viable and sustainable strategies to address the causes of poverty and design schemes to help the poor out of their situation. However, for these schemes to be implemented, the government needs to be able to identify who the poor are. For this there is need to develop a scale to measure poverty, and the factors that make up the criteria for this measurement or mechanism need to be carefully chosen.

In pre-independent India, Dadabhai Naoroji was the first to discuss the concept of a Poverty Line. He used the menu for a prisoner and used appropriate prevailing prices to arrive at what may be called ‘jail cost of living’. However, only adults stay in jail whereas, in an actual society, there are children too. He, therefore, appropriately adjusted this cost of living to arrive at the poverty line. For this adjustment, he assumed that one-third population consisted of children and half of them consumed very little while the other half consumed half of the adult diet. This is how he arrived at the factor of three-fourths; (1/6)(Nil) + (1/6)(Half) + (2/3)(Full) = (3/4) (Full). The weighted average of consumption of the three segments gives the average poverty line, which comes out to be three-fourth of the adult jail cost of living.

chart 4.1: poverty line

In post-independent India, there have been several attempts to work out a mechanism to identify the number of poor in the country. For instance, in 1962, the Planning Commission formed a Study Group. In 1979, another body called the ‘Task Force on Projections of Minimum Needs and Effective Consumption Demand’ was formed. In 1989 and 2005, ‘Expert Groups’ were constituted for the same purpose. Besides the Planning Commission, many individual economists have also attempted to develop such a mechanism.

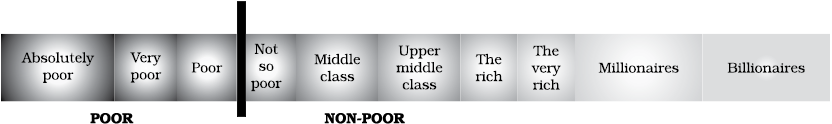

For the purpose of defining poverty, we divide people into two categories; the poor and the non-poor and the poverty line separates the two. However, there are many kinds of poor; the absolutely poor, the very poor and the poor. Similarly, there are various kinds of non-poor; the middle class, the upper middle class, the rich, the very rich and the absolutely rich. Think of this as a line or continuum from the very poor to the absolutely rich with the poverty line dividing the poor from the non-poor.

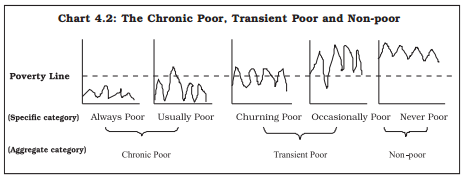

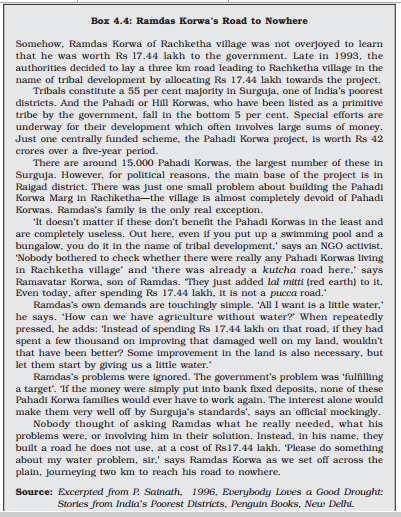

Categorising Poverty: There are many ways to categorise poverty. In one such way people who are always poor and those who are usually poor but who may sometimes have a little more money (example: casual workers) are grouped together as the chronic poor. Another group are the churning poor who regularly move in and out of poverty (example: small farmers

and seasonal workers) and the occasionally poor who are rich most of the time but may sometimes have a patch of bad luck. They are called the transient poor. And then, there are those who are never poor and they are the non-poor (Chart 4.2).

The Poverty Line: Now, let us examine how to determine the poverty line. There are many ways of measuring poverty. One way is to determine it by the monetary value (per capita expenditure) of the minimum calorie intake that was estimated at 2,400 calories for a rural person and 2,100 for a person in

the urban area. Based on this, in 2011-12, the poverty line was defined for rural areas as consumption worth Rs 816 per person a month and for urban areas it was Rs 1,000.

Though the government uses Monthly Per Capita Expenditure (MPCE) as proxy for income of households to identify the poor, do you think this mechanism satisfactorily identifies the poor households in our country?

Economists state that a major problem with this mechanism is that it groups all the poor together and does not differentiate between the very poor and the other poor (See chart 4.2). Also this mechanism takes into account expenditure on food and a few select items as proxy for income, economists question its basis. This mechanism is helpful in identifying the poor as a group to be taken care of by the government, but it would be difficult to identify who among the poor need help the most.

There are many factors, other than income and assets, which are associated with poverty; for instance, the accessibility to basic education, health care, drinking water and sanitation. They need to be considered to develop Poverty Line. The existing mechanism for determining the Poverty Line also does not take into consideration social factors that trigger and perpetuate poverty such as illiteracy, ill health, lack of access to resources, discrimination or lack of civil and political freedoms. The aim of poverty alleviation schemes should be to improve human lives by expanding the range of things that a person could be and could do, such as to be healthy and well-nourished, to be knowledgeable and participate in the life of a community. From this point of view, development is about removing the obstacles to the things that a person can do in life, such as illiteracy, ill health, lack of access to resources, or lack of civil and political freedoms.

Though the government claims that higher rate of growth, increase in agricultural production, providing employment in rural areas and economic reform packages introduced in the 1990s have resulted in a decline in poverty levels, economists raise doubts about the government’s claim. They point out that the way the data are collected, items that are included in the consumption basket, methodology followed to estimate the poverty line and the number of poor are manipulated to arrive at the reduced figures of the number of poor in India.

Due to various limitations in the official estimation of poverty, scholars have attempted to find alternative methods. For instance, Amartya Sen, noted Nobel Laureate, has developed an index known as Sen Index. There are other tools such as Poverty Gap Index and Squared Poverty Gap. You will learn about these tools in higher classes.

4.4 The Number of Poor in India

When the number of poor is estimated as the proportion of people below the poverty line, it is known as ‘Head Count Ratio’.

You might be interested in knowing the total number of poor persons residing in India. Where do they reside and has their number or proportion declined over the years or not? When such a comparative analysis of poor people is made

in terms of ratios and percentages, we will have an idea of different

levels of poverty of people and

their distribution; between states and over time.

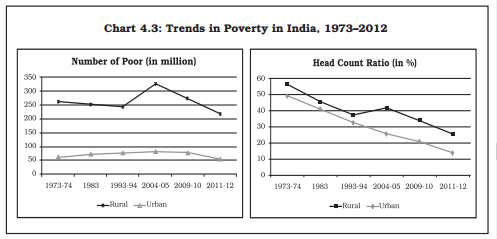

The official data on poverty is made available to the public by the Planning Commission. It is estimated on the basis of consumption expenditure data collected by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO). Chart 4.3 shows the number of poor and their proportion to the population in India for the years 1973-2012. In 1973-74, more than 320 million people were below the poverty line. In 2011-12, this number has come down to about 270 million.

In terms of proportion, in 1973-74,

about 55 per cent of the total population was below the poverty line. In 2011-12, it has fallen to 22 per cent. In 1973-74, more than 80 per cent

of the poor resided in rural areas and this situation has not changed even in 2011-12. This means that more than three-fourth of the poor in India still reside in villages. Why do you think this is the case?

In the 1990s, the absolute number of poor in rural areas had declined whereas the number of their urban counterparts increased marginally. The poverty ratio declined continuously for both urban and rural areas. From Chart 4.3, you will notice that during 1973-2012, there has been a decline in the number of poor and their proportion but the nature of decline in the two parameters is not encouraging. The ratio is declining much slower than the absolute number of poor in the country. You will also notice that the gap between the absolute number of poor in rural and urban areas got reduced whereas in the case of ratio the gap has remained the same until 1999-2000 and has widened in 2011-12.

The state level trends in poverty are shown in Chart 4.4. The two lines in the chart indicate the national poverty level. The first line from below indicates poverty level during 2011-12 and the other line indicates the same for the year 1973-74. This means, the proportion of poor in India during 1973-2012 has come down from 55 to 22 per cent. The chart also reveals that six states - Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal and Orissa - contained a large section of poor in 1973-74. During 1973-2012, many Indian states reduced the poverty levels to a considerable extent. Yet, the poverty levels in four states - Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh are still far above the national poverty level. You may notice West Bengal and Tamil Nadu reduced poverty level much better than other states. How come they were able to do much better than other states?

4.5 What Causes Poverty?

The causes of poverty lie in the institutional and social factors that mark the life of the poor. The poor are deprived of quality education and unable to acquire skills which

fetch better incomes. Also access to health care is denied to the poor. The main victims of caste, religious and other discriminatory practices are poor. These can be caused as a result of (i) social, economic and political inequality (ii) social exclusion (iii) unemployment (iv) indebtedness (v) unequal distribution of wealth. Aggregate poverty is just the sum of individual poverty. Poverty is also explained by general, economy-wide problems, such as (i) low capital formation (ii) lack of infrastructure

(iii) lack of demand (iv) pressure of population (v) lack of social/ welfare nets.

In Chapter 1 you have read about the British rule in India. Although the final impact of the British rule on Indian living standards is still being debated, there is no doubt that there was a substantial negative impact on the Indian economy and standard of living of the people. There was substantial de-industrialisation in India under the British rule. Imports of manufactured cotton cloth from Lancashire in England displaced much local production, and India reverted to being an exporter of cotton yarn, not cloth.

As over 70 per cent of Indians were engaged in agriculture throughout the British Raj period, the impact on that sector was more important on living standards than anything else. British policies involved sharply raising rural taxes that enabled merchants and moneylenders to become large landowners. Under the British, India began to export food grains and, as a result, as many as 26 million people died in famines between 1875 and 1900.

Britain’s main goals from the Raj were to provide a market for British exports, to have India service its debt payments to Britain, and for India to provide manpower for the British imperial armies.

The British Raj impoverished millions of people in India. Our natural resources were plundered, our industries worked to produce goods at low prices for the British and our food grains were exported. Many died due to famine and hunger. In 1857-58, anger at the overthrow of many local leaders, extremely high taxes imposed on peasants, and other resentments boiled over in a revolt against British rule by the sepoys, Indian troops commanded by the British.

Even today agriculture is the principal means of livelihood and land is the primary asset of rural people; ownership of land is an important determinant of material well-being and those who own some land have a better chance to improve their living conditions.

Since independence, the government has attempted to redistribute land and has taken land from those who have large amounts to distribute it to those who do not have any land, but work on the land as wage labourers. However, this move was successful only to a limited extent as large sections of agricultural workers were not able to farm the small holdings that they now possessed as they did not have either money (assets) or skills to make the land productive and the land holdings were too small to be viable. Also most of the Indian states failed to implement land redistribution policies.

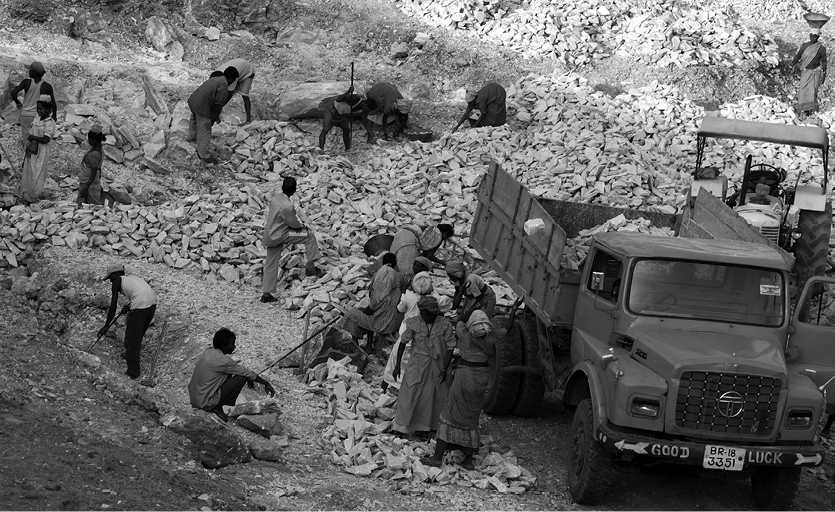

Fig. 4.4 Low quality self-employment sustains poverty

A large section of the rural poor in India are the small farmers. The land that they have is, in general, less fertile and dependent on rains. Their survival depends on subsistence crops and sometimes on livestock. With the rapid growth of population and without alternative sources of employment, the per-head availability of land for cultivation has steadily declined leading to fragmentation of land holdings. The income from these small land holdings is not sufficient to meet the family’s basic requirements.

You must have heard about farmers committing suicide due to their inability to pay back the loans that they have taken for cultivation and other domestic needs as their crops have failed due to drought or other natural calamities (see Box 4.3).

Most members of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes are not able to participate in the emerging employment opportunities in different sectors of the urban and rural economy as they do not have the necessary knowledge and skills to do so.

A large section of urban poor in India are largely the overflow of the rural poor who migrate to urban areas in search of employment and a livelihood. Industrialisation has not been able to absorb all these people. The urban poor are either unemployed or intermittently employed as casual labourers. Casual labourers are among the most vulnerable in society as they have no job security, no assets, limited skills, sparse opportunities and no surplus to sustain them.

Poverty is, therefore, also closely related to nature of employment. Unemployment or under employment and the casual and intermittent nature of work in both rural and urban areas that compels indebtedness, in turn, reinforces poverty. Indebtedness is one of the significant factors of poverty.

Work These Out

Ø You may come across washermen and barbers in your neighbourhood. Spare a few moments and speak to a few of them. Collect details about what made them to take up this activity, where they live with their family members, number of meals they are able to consume in a day, whether they possess any physical assets and why they could not take up a job. Discuss the details that you have collected in the classroom.

Ø List the activities of people in rural and urban areas separately. You may also list the activities of the non-poor. Compare the two and discuss in the classroom why the poor are unable to take up such activities.

A steep rise in the price of food grains and other essential goods, at a rate higher than the price of luxury goods, further intensifies the hardship and deprivation of lower income groups. The unequal distribution of income and assets has also led to the persistence of poverty in India.

All this has created two distinct groups in society: those who posses the means of production and earn good incomes and those who have only their labour to trade for survival. Over the years, the gap between the rich and the poor in India has widened. Poverty is a multi-dimensional challenge for India that needs to be addressed on a war footing.

Box 4.3: Distress Among Cotton Farmers

Many small land owning farmers and farming households and weavers are descending into poverty due to globalisation related shock and lack of perceived income earning opportunities in relatively well performing states in India. Where households have been able to sell assets, or borrow, or generate income from alternative employment opportunities, the impact of such shocks maybe transient. However, if the household has no assets to sell or no access to credit, or is able to borrow only at exploitative rates of interest and gets into a severe debt trap, the shocks can have long duration ramification in terms of pushing households below the poverty line. The worst form of this crisis is suicides. The count reached 3,000 in Andhra Pradesh alone and is rising. In December 2005, the Maharashtra government admitted that over 1,000 farmers have committed suicides in the state since 2001.

India has the largest area under cotton cultivation in the world covering 8,300 hectares in 2002–03. The low yield of 300 kg per hectare pushes it into third position in production. High production costs, low and unstable yields, decline in world prices, global glut in production due to subsidies by the U.S.A. and other countries, and opening up of the domestic market due to globalisation have increased the exposure of farmers and led to agrarian distress and suicides especially in the cotton belt of Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra. The issue is not one of profits and higher returns but that of the livelihood and survival of millions of small and marginal farmers who are dependent on agriculture.

Scholars cite several factors that have led farmers to commit suicides (i) the shift from traditional farming to the farming of high yielding commercial crops without adequate technical support combined with withdrawal of the state in the area of agricultural extension services in providing counselling on farm technologies, problems faced, immediate remedial steps and lack of timely advice to farmers (ii) decline in public investment in agriculture in the last two decades (iii) low rates of germination of seeds provided by large global firms, spurious seeds and pesticides by private agents (iv) crop failure, pest attack and drought (v) debt at very high interest rate of 36 per cent to 120 per cent from private money lenders (vi) cheap imports leading to decline in pricing and profits (vii) lack of access to water for crops which forced the farmers to borrow money at exorbitant rates of interest to sink borewells that failed.

Sources: Excerpted from A.K. Mehta and Sourabh Ghosh assited by Ritu Elwadhi, “Globalisation, Loss of Livelihoods and Entry into Poverty,” Alternative Economic Survey, India 2004-2005, Alternative Survey Group, Daanish Books, Delhi 2005 and P. Sainath, The swelling ‘Register of Deaths’, The Hindu, 29 December 2005.

4.6 Policies and Programmes Towards Poverty Alleviation

The Indian Constitution and five year plans state social justice as the primary objective of the developmental strategies of the government. To quote the First Five Year Plan (1951-56), “the urge to bring economic and social change under present conditions comes from the fact of poverty and inequalities in income, wealth and opportunity”. The Second Five Year Plan (1956-61) also pointed out that “the benefits of economic development must accrue more and more to the relatively less privileged classes of society”. One can find, in all policy documents, emphasis being laid on poverty alleviation and that various strategies need to be adopted by the government for the same.

The government’s approach to poverty reduction was of three dimensions. The first one is growth-oriented approach. It is based on the expectation that the effects of economic growth — rapid increase in gross domestic product and per capita income — would spread to all sections of society and will trickle down to the poor sections also. This was the major focus of planning in the 1950s and early 1960s.

It was felt that rapid industrial development and transformation of agriculture through green revolution in select regions would benefit the underdeveloped regions and the more backward sections of the community. You must have read in Chapters 2 and 3 that the overall growth and growth of agriculture and industry have not been impressive. Population growth has resulted in a very low growth in per capita incomes. The gap between poor and rich has actually widened. The Green Revolution exacerbated the disparities regionally and between large and small farmers. There was unwillingness and inability to redistribute land. Economists state that the benefits of economic growth have not trickled down to the poor.

While looking for alternatives to specifically address the poor, policy makers started thinking that incomes and employment for the poor could be raised through the creation of additional assets and by means of work generation. This could be achieved through specific poverty alleviation programmes. This second approach has been initiated from the Third Five Year Plan (1961-66) and progressively enlarged since then. One of the noted programmes initiated in the 1970s was Food for Work.

Most poverty alleviation programmes implemented are based on the perspective of the Five Year

Plans. Expanding self-employment programmes and wage employment programmes are being considered as the major ways of addressing poverty. Examples of self-employment programmes are Rural Employment Generation Programme (REGP), Prime Minister’s Rozgar Yojana (PMRY) and Swarna Jayanti Shahari Rozgar Yojana (SJSRY). The first programme aims at creating self-employment opportunities in urban areas. The Khadi and Village Industries Commission is implementing it. Under this programme, one can get financial assistance in the form of bank loans to set up small industries. The educated unemployed from low-income families in rural and urban areas can get financial help to set up any kind of enterprise that generates employment under PMRY. SJSRY mainly aims at creating employment opportunities—both self-employment and wage employment—in urban areas.

Earlier, under self-employment programmes, financial assistance was given to families or individuals. Since the 1990s, this approach has been changed. Now those who wish to benefit from these programmes are encouraged to form self-help groups. Initially they are encouraged to save some money and lend among themselves as small loans. Later, through banks, the government provides partial financial assistance

to SHGs which then decide whom

the loan is to be given to for self-employment activities. Swarnajayanti Gram Swarozgar Yojana (SGSY) is one such programme. This has now been restructured as National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM). A similar programme called National Urban Livelihoods Mission has also been in place for urban poor.

The government has a variety of programmes to generate wage employment for the poor unskilled people living in rural areas. In August 2005, the Parliament passed a new Act to provide guaranteed wage employment to every rural household whose adult volunteer is to do unskilled manual work for a minimum of 100 days in a year. This Act is known as Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. Under this Act all those among the poor who are ready to work at the minimum wage can report for work in areas where this programme is implemented. In 2013-14, nearly five crore households got employment opportunities under this law.

The third approach to addressing poverty is to provide minimum basic amenities to the people. India was among the pioneers in the world to envisage that through public expenditure on social consumption needs — provision of food grains at subsidised rates, education, health, water supply and sanitation—people’s living standard could be improved. Programmes under this approach are expected to supplement the consumption of the poor, create employment opportunities and bring about improvements in health and education. One can trace this approach from the Fifth Five Year Plan, “even with expanded employment opportunities, the poor will not be able to buy for themselves all the essential goods and services. They have to be supplemented up to at least certain minimum standards by social consumption and investment in the form of essential food grains, education, health, nutrition, drinking water, housing, communications and electricity.” Three major programmes that aim at improving the food and nutritional status of the poor are Public Distribution System, Integrated Child Development Scheme and Midday Meal Scheme. Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Gramodaya Yojana, Valmiki Ambedkar Awas Yojana are also attempts in developing infrastructure and housing conditions. It may be essential to briefly state that India has achieved satisfactory progress in many aspects.

Work These Out

Discuss and then develop a list of three employment opportunities each that can arise in coastal areas, deserts, hilly tribal areas, tribal areas under : (i) Food for Work Programme and (ii) self-employment.

Ø In your area or neighbourhood, you will find developmental works such as laying of roads, construction of buildings in government hospitals, government schools etc. Visit such sites and prepare a two-three page report on the nature of work, how many people are getting employed, wages paid to the labourers etc.

The government also has a variety of other social security programmes to help a few specific groups. National Social Assistance Programme is one such programme initiated by the central government. Under this programme, elderly people who do not have anyone to take care of them are given pension to sustain themselves. Poor women who are destitute and widows are also covered under this scheme. The government has also introduced a few schemes to provide health insurance to poor people. From 2014, a scheme called Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana is available in which people in India are encouraged to open bank accounts. Besides promoting savings habit, this scheme intends to transfer all the benefits of government schemes and subsidies to account holders directly. Each bank account holder is also entitled to Rs. 1 lakh accident insurance and Rs. 30,000 life insurance cover.

4.7 Poverty Alleviation Programmes — A Critical Assessment

Efforts at poverty alleviation have borne fruit in that for the first time since independence, the percentage of absolute poor in some states is now

well below the national average. Despite various strategies to alleviate poverty, hunger, malnourishment, illiteracy and lack of basic amenities continue to be a common feature

in many parts of India. Though the policy towards poverty alleviation has evolved in a progressive manner, over the last five and a half decades, it has not undergone any radical transformation. You can find

change in nomenclature, integration or mutations of programmes. However, none resulted in any radical change in the ownership of assets, process of production and improvement of basic amenities

to the needy. Scholars, while assessing these programmes, state three major areas of concern which prevent their successful implementation. Due to unequal distribution of land and other assets, the benefits from direct poverty alleviation programmes have been appropriated by the non-poor. Compared to the magnitude of poverty, the amount of resources allocated for these programmes is not sufficient. Moreover, these programmes depend mainly on government and bank officials for their implementation. Since such officials are ill motivated, inadequately trained, corruption prone and vulnerable to pressure from a variety of local elites, the resources

are inefficiently used and wasted.

There is also non-participation of local level institutions in programme implementation.

Government policies have also failed to address the vast majority of vulnerable people who are living on or just above the poverty line. It also reveals that high growth alone is not sufficient to reduce poverty. Without the active participation of the poor, successful implementation of any programme is not possible.

Fig. 4.7 Scrap collector: mismangament of employment planning forces people to take up very low paying jobs

Poverty can effectively be eradicated only when the poor start contributing to growth by their active involvement in the growth process. This is

possible through a process of social mobilisation, encouraging poor people to participate and get them empowered. This will also help create employment opportunities which may lead to increase in levels of income, skill development, health and literacy. Moreover, it is necessary to identify poverty stricken areas and provide infrastructure such as schools, roads, power, telecom, IT services, training institutions etc.

4.8 Conclusion

We have travelled about six decades since independence. The objective of all our policies had been stated as promoting rapid and balanced economic development with equality and social justice. Poverty alleviation has always been accepted as one of India’s main challenges by the policy makers, regardless of which government was in power. The absolute number of poor in the country has gone down and some states have less proportion of poor than even the national average. Yet, critics point out that even though vast resources have been allocated and spent, we are still far from reaching the goal. There is improvement in terms of per capita income and average standard of living; some progress towards meeting the basic needs has been made. But when compared to the progress made by many other countries, our performance has not been impressive. Moreover, the fruits of development have not reached all sections of the population. Some sections of people, some sectors of the economy, some regions of the country can compete even with developed countries in terms of social and economic development, yet, there are many others who have not been able to come out of the vicious circle of poverty.

Recap

EXERCISE

1 why calorie - based norm is not adequate to identify the poor?

2. What is meant by ‘Food for Work’ programme?

3. Why are employment generation programmes important in poverty alleviation in India?

4. How can creation of income earning assets address the problem of poverty?

5. The three dimensional attack on poverty adopted by the government has not succeded in poverty alleviation in India. Comment.

6. What programmes has the government adopted to help the

elderly people and poor and destitute women?

7. Is there any relationship between unemployment and poverty? Explain.

8. Suppose you are from a poor family and you wish to get help from the government to set up a petty shop. Under which scheme will you apply for assistance and why?

9. Illustrate the difference between rural and urban poverty. Is it correct to say that poverty has shifted from rural to urban areas? Use the trends in poverty ratio to support your answer.

10. Suppose you are a resident of a village, suggest a few measures to tackle the problem of poverty.

1. Collect data from 30 persons of your locality regarding their daily consumption of various commodities. Then rank the persons on the basis of relatively better off and worse, to get the degree of relative poverty.

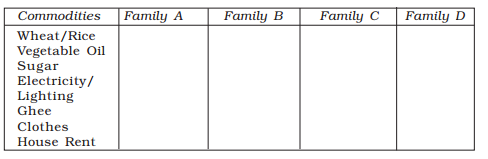

2. Collect information and fill in the following table with the amount of money spent in terms of rupees by four low income families on various commodities. Analyse the research and find out which family is relatively poor in comparison to the other families. Also find out who are absolutely poor if the poverty line is fixed at an expenditure of Rs 500 per month per person.

2. The following table shows the average monthly expenditure per person on items of consumption in India and Delhi slums in terms of percentage. ‘Rice and wheat’ in rural areas at 25 per cent means that for every 100 rupees spent, Rs 25 goes towards the purchase of rice and wheat alone. Read the table further and answer the questions that follow.

• Compare the percentage of expenditure on food items among different groups and their priorities.

• Do you think households in slums are depending more on cereals and pulses?

• On which item do people living in different areas spend the least? Compare them.

• Do you think that slum dwellers have given more emphasis to meat, fish and eggs?

Books

Dandekar, V.M. and Nilakantha Rath. 1971. Poverty in India, Indian School of Political Economy, Pune.

Dreze, Jean. Amartya Sen & Akthar Husain (Eds.). 1995. The Political Economy of Hunger. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Naoroji, Dadabhai. 1996. Poverty and Un-British Rule in India, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, Second Edition, New Delhi.

Articles

Kumar, Naveen and S.C. Aggarwal. 2003. ‘Pattern of Consumption and Poverty in Delhi Slums.’ Economic and Political Weekly, December 13, pp. 5294-5300.

Minhas, B.S., L.R. Jain and S.D. Tendulkar. 1991. ‘Declining Incidence of Poverty in the 1980s—Evidence versus Artefacts,’ Economic and Political Weekly, July 6-13.

Government Reports

Report of the Expert Group of the Estimation of Proportion and Number of Poor, Perspective Planning Division, Planning Commission Government of India, New Delhi, 1993.

Economic Survey (for various years). Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

Tenth Five Year Plan 2002-2007, Vol. II: Sectoral Policies and Programmes, Planning Commission, Government of India, New Delhi.

Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012-17), Vols. I, II and III. Sage Publications Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi (for Planning Commission, Government of India).