Table of Contents

Chapter 5

INDIGENOUS GRAPHIC DESIGN PRACTICES

Is graphic design only a modern idea or do we have art practices from earlier times which could be called graphic design practices? Do only the urban educated practise graphic design or can we find art practices in tribal and rural areas among people and communities that are not educated in a modern way?

What do you think? Yes, we can see many art activities that come under graphic design among the pre-modern and traditional people and communities. It ranges from drawings on thresholds to corners, walls, roofs and front-yards of houses. The list goes on to the handloom cloth, ceramic decorations, tattoos, designs on hands and palms such as the mehendi to religious icons and yantras, talismans, walls and roofs of temples and forts in India and so on. All the art activities can be distinguished from the modern or contemporary graphic design practices and may be called indigenous graphic design traditions or traditional graphic design practices.

Based on the tradition to which they belong, living Indian indigenous graphic designs and motifs may broadly be classified as under:

Vedic and earlier design practices

Folk and popular traditions

Tribal design practices

Tantric design practices

Figure 5.1 A Yajna ritual

VEDIC AND EARLIER DESIGN PRACTICES

To an extent, the above traditions are mutually connected. But there are several possible ways in which these strands could be connected to each other. The connection between earlier traditions is well known and undisputed. The early design practices are widely accepted as the later and popular form of the Vedic. But the problem whether Tantric has Vedic connections or it is an autonomous tradition or it has folk/tribal origins is not yet settled. There is a possibility of connecting both Puranic and Tantric traditions to Vedic traditions on the one hand and to folk and tribal traditions on the other.

Figure 5.2 Vedic symbols

In Vedic rituals, Yajnas are the rituals of dedicating materials through fire to various gods and goddesses. These Yajnas and such as Shraaddha karmas (ancestor worship rituals), rites such as marriage-rites, etc., shapes such as circle, square and triangle are used to represent and invoke different gods and goddesses. For example in a Shraaddha karmas, a circle is drawn by the Karta (performer of the ritual) with his finger on water smeared by him on the floor, to invoke the spirit of the ancestor being worshipped by him in that ritual and a square is drawn in a similar fashion to invoke the gods called Visvedevas.

More complex figures are drawn with finger with white rice powder on the raised platform or floor prepared by mud to invoke various Vedic gods as part of Yajnas

The script symbol for the most vital speech sound of Vedic culture, pronounced as Om and called Pranava, is one of the most significant graphic representation in this culture.

Many other such powerful graphical symbols such as swastika can be traced to Vedic graphic symbolism.

FOLK AND POPULAR TRADITIONS

Non-vedic, non-modern, rural traditions are usually classified under 'folk' traditions. There is a controversy about whether these traditions are pre-vedic or not. Whatever is the truth in this regard, as we find them today most folk traditions are either influenced by or usually in some way are connected to vedic tradition. There is evidence of influence of folk traditions on Vedic tradition or absorption of folk tradition into Vedic tradition also. There is a great part of folk tradition that is continuing with little influence from Vedic tradition.

Folk and puranic traditions include popular cultural and artistic practices that may be religious or secular in nature. These practices, by and large, have evolved in the form of customs, profession or artistic traditions. Some of such folk and puranic design practices are discussed below.

Threshold Decorations

Traditionally in Indian villages, front yard or threshold is either plastered by mud or cow dung and some drawings are made on specially prepared walls and floor. The threshold could be understood as an intermediary space between the outer and the inner world of the home. The function of this, at a superficial level, seems to be purely that of a decoration. But there are studies that show the origin of this practice in the notion of fertility and magical (supernatural) beliefs around them.

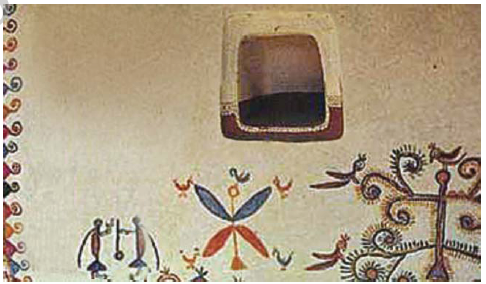

Figure 5.3 A front yard decoration with space to keep oil lamp

Usually, the drawings are made in powder. This powder appears to be white in colour in most parts of India. In some parts this white powder is powdered from a soft brittle white stone. But today, in most places, rice flour is being used for this purpose.

Figure 5.4 A swastika is designed on wall

Although they vary in name, material, and part of the house they are made in from region to region, these are exclusively done by the women folk on the threshold of the house, according to knowledge passed on from one generation to another, from mother to daughter. This gender exclusivity has given this design form a feminine identity understood in a social setting where women were limited to a certain work-area of the household.

Figure 5.5 Threshold decoration on floor

Figure 5.6 Making design on floor

The practice of decorating floor is known with different names as Alpana or Alpona in Bengal, Aripana in Bihar, Jhuniti in Orissa, Mandna in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, Salhiya in Gujarat, Rangoli in Maharashtra, Muggu in Andhra Pradesh and , Kalamezhuthu in Karnataka,Kolam in Tamil Nadu and Kerala and Chowkpurna in Uttar Pradesh it is known as or Aripan.

In Kerala, the design's outlines are filled in by flowers, while in Orissa, Rajasthan and other parts of North India, the design is made from a mixture of rice flour and water and is applied with the finger piece of cloth or a brush. While in North India, they are mostly done during religious festivals or during vratas. In South India the kolam is practised daily.

Alpana/Alpona/Aripana/Rangoli/Jhuniti

Alpana is made by women of the household during the days of festivities and religious functions in front of households in Bengal. They are drawn on the ground by means of a small piece of cloth wrapped round a finger which is soaked in thin paste of grounded rice mixed with water.

These drawings are connected with certain rites performed exclusively by matrons (nari vrata) and virgins (kumari vrata) or by priests on behalf of women (sashtriya vrata) are rites for the realisation of special wishes and performed according to rules transmitted from generation to generation not confined to any religious cult or special sect. As evident, these are done by people with rudimentary skill inputs. The forms could be understood as a kind of picturewriting using simple-forms and shapes (calligraphic simplification of objects). These forms are utilised to create designs/narratives of varying complexities as a testimonial of their desire and wishes through an alpana.

Figure 5.7 Different forms used as motifs

Also prevalent among them is a sense of decoration/ ornamentation as seen in the various innovative creeper and lotus motifs associated with the alpana. But when they are taken out of this contextual setting of rituals as part of fulfilment of vows they become mere objects of decoration.

In the Mithila region in Bihar Aripana is done by Brahmana and Kayastha ladies closely associated to religious rituals. Using their fingers they create graceful lace like designs on the mud floor of homes and courtyards. Colour is added with the blood red vermilion powder in the form of dot like patterns. The material like turmeric, rice and wheat powder used is called Aripan.

Moving out from the domestic threshold drawings done by women we look into another form of sand painting practised in the temples of Kerala. This requires more accomplished skill and greater precision through traditionally prescribed and mandated at different hierarchy levels.

Figure 5.8 Kalamezhuthu

Temporal in nature this Kalamezhuthu is conducted as part of the general festivities in the temple, or as part of a major ritual, and is immediately erased after the ritual is over. This colourful ritual is done by hands without using any tools using powdered pigments extracted from natural mineral, vegetable or combined sources.

Kolam

Kolam is mainly done with the belief to bring wealth and prosperity into the household. The welcoming/inviting gesture of the kolam could be understood in a larger context, where the coarse rice material ingredient with which the kolam is done acts as a means to invite insects, birds and other small creatures to eat it, thus inviting other beings into one's home and everyday life as a tribute to harmonious co-existence. This becomes more ironic in today's world of fragmentary values, and overall environmental degradation.

On the other hand, the designs are also believed to sanctify the threshold and make the house auspicious, pure and protected from the inauspicious, impure and dangerous outside world. The closed lines symbolically prevent the evil spirit from entering the shapes and therefore prevented from entry into the house. If the threshold is not constantly sanctified by the Kolam, inauspicious forces may trespass into the home and eventually disrupt the health and well-being of the family. Thus, this function of warding off inauspicious forces at the threshold is performed.

Figure 5.9 Kolam

The structural basis of a Kolam is the predetermined matrix of dots (pullis), that acts as simple structural unit on the basis of which the patterns are formed either by joining the dots or looping around them to create the designs. Work circuits of various strata with varying degrees of sophistication, skill inputs could be seen in any culture ranging from people with rudimentary skill trying to fashion out symbols to render the visual facts around them, to the more complicated, more individual and sophisticated forms of design on textiles.

Floor decorations of various kinds could be seen all over India and it would be interesting to research into the formal peculiarities and nuances in floor decoration pertaining to one's locality.

Kalamkari

Kalamkari or Qalamkari is a type of hand-painted or blockprinted cotton textile produced in parts of India for hanging on walls. The word is derived from the Persian words kalam (pen) and kari (craftmanship), meaning drawing with a pen. Kalamkari tradition is very old and flourished in Coromandel and the wealthy Golconda Sultanate of Hyderabad, in the middle age it was traded to Persia. This art was patronised by the Mughals particularly in Golconda.

Figure 5.10 A Kalamkari with events from Ramayana

There are two distinctive styles of Kalamkari design in India one, the Srikalahasti style and the other, the Masulipatnam style of art. Both the style are different in practice. The Masulipatnam style of Kalamkari is influenced by Persian art The motifs used are trees, flowers and leaf designs are printed using blocks. The Srikalahasti style flourished around temples with Hindu patronage, thus has an almost religious identity, wherein the or pen is used for freehand drawing of the subject, and filling in the colours is entirely done by hand. The themes and deities are drawn from great epics like Ramayana, Mahabharata, Puranas and other mythological classics. These are depicted on scrolls, temple hangings and chariot banners.

In the execution of design in both the styles only natural dyes are used. The cotton fabric gets its glossiness by immersing it for an hour in a mixture of myrobalan (resin) and cow milk. Then contours and themes are drawn with a pointed bamboo (kalam) soaked in the mixture; and then one by one the vegetable dyes are applied by hand and/ or block. After each colour the Kalamkari is washed. Thus, each fabric can undergo up to 20 washes. Various effects are obtained by cow dung, seeds, plants and crushed flowers.

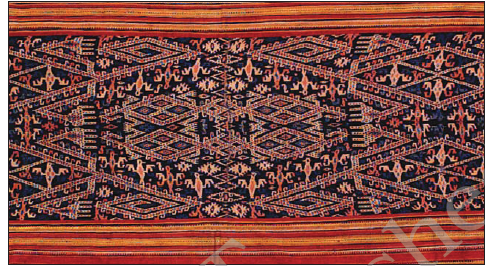

Ikat

Ikat or Ikkat means 'to tie' or 'to bind' and describe both the process and the cloth itself. Ikat and duble Ikats have cultures with long histories of production in South-East Asia. Ikat is a process of weaving that uses a resist dyeing technique similar to tie-dye on either the warp or weft before the threads are woven to create a pattern or design. When both the warp and the weft are tie-dyed before weaving it is known as double Ikat.

Figure 5.11 An Ikat cloth

Patola cloth, a double Ikat from Gujarat and Pchampally Ikat from Andhra Pradesh are indigenous practices of textile designing in India. Like any craft or art form, Ikat vary widely from place to place and region to region. Designs may have symbolic of ritual meaning. Ikats are often symbols of status, wealth, power and prestige. Perhaps because of the difficulty and time required to produce an Ikat.

The easiest way to create Ikat is that the warp strings are arranged into bundles before they are attached to the loom. Each bundle is tied and dyed separately, so that a pattern will emerge when the loom is set up. This takes a good deal of skill. The tightly bound bundles are sometimes covered with wax or some other material as resist. In resist technique a medium (wax) is used, it keeps the dyes (water soluble) from penetrating, as both (wax and dye) repel each other. The process is repeated several times for additional colours. Sometime each strand of the cloth may be dyed differently from the ones next to it. After the threads are dyed the loom is set up. Ikat fabrics are woven by hand on narrow looms in a laborious process. The pattern is visible to the weaver when the dyed threads are used as warp. Threads can be adjusted so that they line up correctly with each other.

Double Ikats are the most difficult to produce, the warp and the weft are precisely tied and dyed so that the patterns interlock and reinforce each other when the fabric is woven. The uniqueness lies in the transfer of design and colouring onto warp and weft threads first and then weaving them together. The fabric is cotton, silk and sico on a mix of silk and cotton. Increasingly, the colours and their blends themselves are from natural sources. The weavers from the older and new generation have adapted themselves to the changing tastes of society and are creating untraditional design.

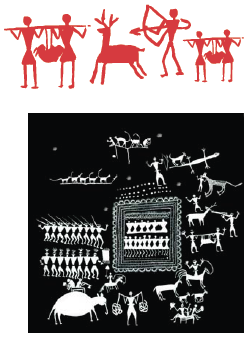

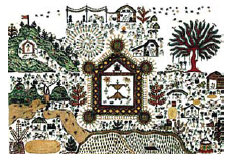

TRIBAL DESIGN PRACTICES

The tribal society has been practising their rituals with pictorial writing which could be argued further in the wall decorations done in various parts of India from the Saora pictographs to the Madhubani or Warli. All these depict their lore and ritualistic functions. These pictographs also act as modes of communication repository of mythological tales, history and even glimpses of daily life as seen in the Warli wall decorations: painting figures and diagrams was the only way for these unlettered people to transmit their hereditary knowledge, folklore and good wishes.

Figure 5.12 A tribal design

The pictorial format of these wall decorations uses extremely basic graphic vocabulary to create their pictorial narratives. Simple elements like square, circle, triangle, semicircle act as elementary form units like alphabet in a language to build up signifiers of varying degrees of correspondence. The circle and triangle come from their observation of nature; the circle representing the sun and the moon, the triangle derived from mountains and pointed trees. Only, the square seems to obey a different logic and seems to be a human invention, indicating a sacred enclosure or a piece of land.

The figures as represented in a Saora or Warli pictographs are the inverted triangle or two triangles joined at a point. The upper triangle represents the upper torso while the lower as the abdomen. Head is represented by a small circle and a smaller circle in conjunction with larger circle is for the female. When circle drawn together with lines for the legs and hands, a human form appears. Through this kind of similar other signifiers, they create the narratives of various complexities. These narratives evolved a kind of picture writing which forms an essential aspect of these wall decorations.

Saora Pictograph: A Case Study

Saora (Saura) in Orissa is a traditional way of their life. The elaborated pictographs drawn in white is also called ittals or idittal. Let us now look into a Saora pictograph to delve more into the communicational efficacy of these signs. Saora paintings or Ittals are made in honour of the dead, to avert disease, to promote fertility and on occasions of certain festivals. Done on the wall of the house, freshly washed with red clay which acts as the canvas, the paint made with a mixture of powdered rice mixed with water is applied with twigs slightly frayed at the end.

Figure 5.13 A Saora pictograph

In the given pictograph, there is a palace in the centre which is represented by the rectangular enclosure with people dancing in it. The human forms are depicted through a combination of rudimentary graphical elements like triangles, circles and simple lines for hands and feet. On a tree outside, monkeys are dancing with joy. Approaching the building is Jaliyasum's mother, sisters and daughters dancing in a row and is protected by police carrying guns on their shoulders. Sun, moon and stars represented by circle, semicircle and dots shine upon the scene. Another god comes to attend the marriage on an elephant. For making drawing of an elephant, they first make the body with triangles then add legs, tail and the trunk and eventually white is filled in the body and rider is drawn. The horse is drawn by two opposite triangles like that of the human figure but tilted on the side. The potter brings pots for rice-beer. A local chieftain comes on a mare followed by its foal; he brings two she-goats for the marriage feast. Two men bring in a sambar killed by God's servants. The range officer also attends and sits with his family on chairs (indicated by the parallel lines). An unwanted guest is caught by Jaliyasum's dog a tiger (indicated by the stipples) and another dog attacks a lizard while a man shoots at it with bow and arrow.

Simple marks like the hatched line, dots or curvilinear lines not only gives a graphical splendour to the motifs but also are ritualistic symbols of hair, quills, leaves, etc. With this repertory of characters of finite elements they create infinite number of signifiers. These signifiers represent their dreams and folklore in pictorial poetry and prose with vibrant details for effective communication which is attested in the charming simplicity of these designs.

Pithora Bhil Paintings: A Case Study

Pithora paintings are much more than ritual colourful images on walls for the tribes of Rathwas, Bhils and Naykas of Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. They signify the advent of an auspicious occasion for celebrations like wedding, childbirth, festivals in the family or community. This celebration and joy reflect in Pithora paintings with their colours and animated figures. These paintings on the walls of their houses have belief that it would enhance their fortune and keep poverty out of their lives.

These paintings mostly depict the marriage procession of Baba Pithora and Pithori Devi, the two gods worshipped by the tribals. Other gods, animals and characters from the Hindu mythology are also included in the paintings. The complete process of making these paintings reflects and reminds the art practice inspired by tradition and culture. Apart from this, the paintings also depict the daily lives of the people. Therefore, farmers, women, animals and insects and other objects are also represented in the paintings.

Figure 5.14 A Bhil painting

The materials for painting are prepared by mixing colour pigments with milk and liquor prepared from the Mahua tree. Pithora paintings are more of ritual practice than an art form. The first wall of the house is considered to be the right place for a painting of Pithora. The identified walls to be painted are first plastered with a thick mixture of mud and cow dung. This is done by the unmarried girls in the family. Then it is coated with chalk powder and this preparation process is called lipna. After lipna the painters proceed to create their work which is done by males. Pithora painting ritual is a male performing process unlike that of alpana, kolam, warli or madhubani.

A Pithora painting is drawn or composed within a rectangular enclosure with an opening at the centre from the bottom border. Everything which has concern with Bhil tribal life is represented and painted. The figures included are tigers, elephants, goats, camels, banyan trees, insects, scorpions, chameleons, beehives; deities and mythological figures, farmer ploughing the field, women churning butter and hunters carrying games and so on. Above all, the boldly drawn and centrally placed figures of horses of the Baba Pithora and the deities. These are shown either riding the horse or represented as horses. The horse also represents as the repository of fertility and power which is an important preoccupation of the Bhil tribe.

TANTRIC DESIGN PRACTICES

Tantra is one of the most prominent traditions of religious practices in India. Though what Tantra is and what its origin is interpreted differently by different people. The most conspicuous and well known aspect of Tantra is its association with graphic icons known as Yantras.

Figure 5.15 Tantra design

Yantra is one of the three essential elements of Tantra tradition, namely Mantra (the syllables viewed as magical spells), Yantra, the graphic icon and Tantra, the actual action such as meditation, offerings, etc. The practitioner of Tantra concentrates his/her appearance on Yantra and meditates on it. This action is believed to be capable of giving supernatural powers and experience to the practitioner. Since Tantra is often practised by the learned, there is a large amount of literature giving theoretical interpretations to each element of the Yantra figures. This literature shows how the metaphysics is represented by these drawings. But an interesting aspect of this tradition is that the yantras are believed to be capable of giving their intended effect irrespective of whether the person meditating on it knows this meaning or not.

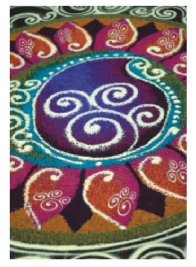

Mandala

In Hindu and Buddhist Tantricism, a symbolic design is used in performance of sacred rites and also as an instrument of meditation. For this purpose, a design is created and is called Mandala.

The concept of Mandala was prevalent during the Vedic age. All the hymns of Rigveda are classified in ten classes which are called Mandalas. Mandala indicates cyclical property. There was a strong Vedic tradition to recite Vedic hymns in a cyclical manner. For instance, there are 191 hymns in the tenth Mandala of Rigveda. Therefore, 191 Vedic priests used to sit in a circle. Then the first priest used to recite the first hymn of the Mandala. Then the 96 priest used to recite the second hymn. Then again the second priest used to recite the third hymn and the fourth hymn is recited by the 97 priest. Likewise, all the hymns of a Mandala were recited in this fashion. In this arrangement, there are two interesting graphical patterns. Firstly, probably the circular sitting arrangement is visualised to symbolically represent the cyclical nature of the world phenomenon and secondly, the pattern of recitation follows diametrically opposite sequence or order of recitation of hymns indicating that the Mandala is formed by connecting diametrically opposite points. The symbolic meaning of the ritual is not known today. However, it is evident that the word Mandala was ascribed to the classification system of Vedic hymns due to this tradition of cyclical recitation.

Figure 5.16 A Mandala

The Mandala is basically a representation of the universe, a consecrated area that serves as a receptacle for the gods and as a collection point for universal forces. Men (the microcosm), by mentally 'entering' the Mandala and 'proceeding' towards its centre, is by analogy guided through the cosmic processes of disintegration and reintegration. Mandalas are rich with symbolism that evokes various aspects of Buddhist teaching and tradition. This is part of what makes the creation of a Mandala a sacred act for imparting the Buddha s teachings. Mandalas are works of sacred art in Tantric (Tibetan) Buddhism. The word Mandala comes from a Sanskrit word that generally means circle and Mandalas are indeed primarily recognisable by their concentric circles and other geometric figures. Mandalas are far more than geometical figures and are rich with symbolism and sacred meaning. A Mandala is usually made with careful placement of coloured sand, and accordingly is known in Tibetan as dul-tson-kyil-khor, or Mandala of coloured powders. Later on, the concept of Mandala is used in many religious and cultural practices. In China, Japan and Tibet, Mandalas are also made in bronze or stone as three-dimensional figures.

Constructing a Mandala

The process of constructing a Mandala is a sacred ritual with a meditative, painstaking process that can take days or even weeks to complete. Before participating in the construction of a Mandala a monk must undergo a lengthy period of artistic and philosophical study and this period may last up to three years. Traditionally, four monks work together on a single Mandala. The Mandala is divided into quadrants with one monk assigned to each. Midway through the process, each monk receives an assistant who helps fill in the colours while the primary monk continues to work on detailed outlines.

Mandalas are constructed from the centre outward, beginning with a dot in the centre. With the placement of the centre dot, the Mandala is consecrated to a particular deity. This deity will usually be depicted in an image over the centre dot, although some Mandalas are purely geometric.

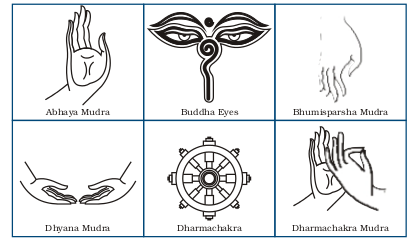

Figure 5.17 Graphical symbol in Buddhism

Lines are then drawn through the centre dot to the four corners, creating triangular geometric patterns. These lines are then used to construct a square 'palace' with four gates. The monks usually keep to their own quadrant at this point. From the inner square, the monks move outward to a series of concentric circles. Here the monks work in tandem, moving all around the Mandala. They wait until each section is entirely completed before moving outward together. This ensures the maintenance of balance in composition.

The square structure in the middle of a Mandala is a palace for the resident deities and a temple containing the essence of the Buddha. The square shaped temple's four elaborate gates symbolise a variety of ideas, including:

The four boundless thoughts: kindness, compassion, sympathy and equanimity.

The four directions: east, west, north and south.

The images of the deities are within the square palace or temple, which are usually the Five Dhyani Buddhas (the Great Buddhas of Wisdom). The iconography of these deities is rich in symbolism in itself. Each of the Dhyani Buddhas represents a direction (centre, south, north, east and west), cosmic element (like form and consciousness), earthly element (of air, water, earth and fire), and a particular type of wisdom. Each Buddha is empowered to overcome a particular evil, such as ignorance, envy or hatred. The Five Dyani Buddhas are generally identical in appearance, but each are represented iconographically with a particular colour, mudra (hand gesture), and animal.

Figure 5.18 Buddhist symbols used as motifs in graphic designs

Outside the square temple are several concentric circles. The outermost circle is usually decorated with stylised scroll work resembling a ring of fire. This ring of fire symbolises the process of transformation for humans to undergo before being able to enter the sacred territory within. It symbolises the burning of ignorance. The next circle inward is a ring of thunderbolt or diamond scepters, which stands for indestructibility and illumination. This is followed by a circle of eight graveyards, representing the eight aspects of human consciousness that bind a person to the cycle of rebirth.

Finally, the innermost ring is made of lotus leaves, signifying religious rebirth. In the centre of the Mandala is an image of the chief deity, who is placed over the centre dot described above. Because it has no dimensions, the centre dot represents the seed or centre of the universe. Although some Mandalas are painted and serve as an enduring object of meditation, the traditional Tibetan sand Mandala, when completed, is deliberately destroyed.

Common features:

The following are some of the common features of the living indigenous graphic designs all over the world in general and in India in particular.

Magical/religious/ supernatural beliefs about graphic design (attribution of supernatural powers to graphic designs).

Transcendental/ supernatural response in the beholding tradition bearers.

Ritual use and ritual origin of the design.

Religious association of the designs.

Use of natural/ nature-friendly tools and materials for drawing and the consequential environmental/ ecological influence on the form (lines, shapes and colours and the technique, structure and style of their use).

The sand is poured into a nearby stream or river to distribute the positive energies it contain. The ritual reminds of those who painstakingly constructed the 'Mandala' — the symbolism of 'impermanence of all things' — the centrality of the Buddhist teachings.

Apart from these living traditions, there are certain extinct traditions which could be found only on archaeological sources and other such documents that are no longer in use by any community. But the purely aesthetic/artistic/ decorative aspect of graphic design is still not totally absent in these indigenous traditions. In fact, some of the graphic design traditions that started as religious traditions used in a ritual context gradually got transformed into artistic and decorative practices.

Projects

1. Develop a project on "Objects change their meaning according to their contextual placements". The entire project should be presented in a documentation format using drawings, pictures or photographs taken by the students themselves. Choose interesting ways of presenting your files.

2. Document similar practices with objectives in other forms of wall decorations in the immediate environment.

Exercises

1. How are kolam designs different from alpana designs? Explain with drawings.

2. Write 10 lines about the cultural aspect of a alpana design.

3. What form of design practice has a feminine identity? Explain.

4. With reference to the Saora describe the importance of tribal art.

5. Tantra is one of the most prominent traditions of religious practice in India. Explain.

6. How the process of constructing a Mandala is a painstaking process?

Practicals

1. Study and identify design practices within your own locality and document their peculiarities and diversities.

2. Explore the floor decorations of various kinds in the immediate environment and document their pictorial formal peculiarities and nuances.

3. Prepare a colour design with pattern formation in the size of 5 cm by 15 cm.

4. Select a few utilitarian objects of your choice and design five different ways of their representational use.