Table of Contents

3

Stone

Even today the stone carvers of Tamil Nadu begin with a prayer that first begs forgiveness from Mother Earth for cutting the stone. The prayer ends with offerings of sweets and milk to the earth and a solemn promise never to misuse or waste stone.

The stone cutter starts by locating a good stone quarry. Then begins the process of cutting what he needs from the mother rock. Metal pegs are hammered in a straight line into the rock at intervals. Water is poured on to the rock to wet it. The change in night and day temperatures causes contraction and expansion and the rock gradually slits along the straight peg lines into perfect slabs.

The most interesting part of the creative process is when the artist chooses the stone piece to work on. How does he decide which is the perfect piece of rock to use? What qualities of the rock does the artist look for — colour or grain or texture, or the softness or hardness of the stone? Can he ‘see’ the image within the rock piece? Can he imagine what its form will be or can he tell by touch how it will feel when it is completely carved?

Types of Stone

There are myriad varieties of stone to be found in India. Soft soap stone contrasts with the hard granite, an igneous rock of the Deccan. Sedimentary rocks of the northern plains of India produce a variety of coloured sandstones; and metamorphic rocks, hardened over centuries under the soil form marble and limestone.

Relief sculpture, Halebid, Karnataka

Rocks acquire their properties from minerals that give them colour, lustre, and strength. Depending on how the rock was formed, igneous or sedimentary, its molecular structure enhances it with a grain, layers and patterns.

Each type of rock, be it granite or sandstone, has intrinsic qualities that the sculptor explores when he creates a work of art.

The nature of the stone will determine how the sculpture is made and also its possibilities. Soft soap stone allows for delicate, intricate carving whereas sandstone, a fragile sedimentary rock with layers of fine compressed sands and grains, has to be handled with extreme care as it breaks easily.

Within each category of stone there is enormous variety. Sandstone ranges from the golden yellow of Jaisalmer to the soft pitted and speckled stone of Mathura and Fatehpur Sikri. The sculptors of India have been using these stones for the past five thousand years.

Descent of Ganga in granite, Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu

The difference in treatment of one stone from another in the hands of an artist can be seen in the granite sculptures of Mahabalipuram and the sandstone figures of Khajuraho. Hard granite stone was used in South India to make temples and household items like grinding stones. The quality of stone available in each region of India distinguishes the style and form that can be created.

Carving

Once the stone is selected the measurements for rough-hewing and cutting of the sculpture are taken. Carving is a difficult process, requiring skill, concentration and extreme caution. It is a process in which forms are cut away or subtracted from the original solid material.

Carving is a process in which forms are cut away or subtracted from the original solid material.

A block of stone is carved by chiselling away tiny chips in order to create the desired shape. Once the stone has been carved the chips cannot be put back or replaced. This means the artist has to have a precise and accurate idea of how far to carve and what to remove. One cannot afford to make mistakes in this process for once the stone is cut away or carved it cannot be put back. Imagine the acumen needed to plan in advance the shape of the face, the size of the smile and the right angle of the jewel that will adorn a carved image. Once the rough work is over, details are carved with finer tools and then the stone is polished. Some stones can be polished to shine like a mirror.

Types of Stone Works

Stone objects include household objects like bowls, plates, grinding stones, and pillars, beams and brackets for construction of houses.

Figures made in solid materials like stone are further classified into categories that explain their technical dimensions:

♦ Relief-sculptured panels

♦ Three-dimensional figures in the round.

Relief-sculptured Panels: A relief has carvings only on one side. The carving can be shallow or deep while the other side is flat and is usually embedded into the masonry work of the building. A low relief can be 1–3 cm deep and high. Relief can almost look like a three-dimentional sculpture.

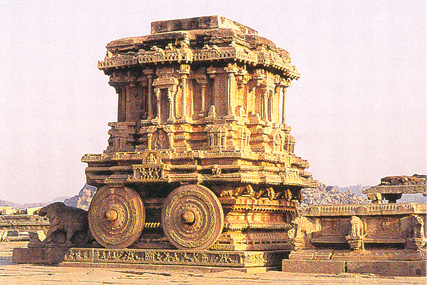

Three-dimensional Figures: Such figures can be viewed from all sides. They can also be used to create free-standing pillars like those erected by Ashoka throughout his empire in the third century BCE.

Three-dimensional figure: torso of Vishnu in red sandstone, Mathura,

Uttar Pradesh

Low relief: Mahakapi Jataka, Bharhut, Madhya Pradesh

Stone Sculpture through the Ages

At Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh, there are a number of rock shelters of the Stone Age period. Early inhabitants lived in natural caves and created fine tools and flints of agate and other natural stones in the area. These tiny flints and well-carved stone implements are the first examples in the long story of Indian sculpture.

At Ellora, in Maharashtra, there are Hindu, Buddhist and Jain rock-cut shrines. The Kailash temple at Ellora of the ninth century is an entire temple that was carved out of the natural hillside. The temple is really a massive sculpture cut out of a single piece of the hill. The artists started work from the top and carved downwards, beginning with the towering roof, the windows, the doors through which one enters into halls with enormous sculptured panels.

View of Kailashnath Temple, Ellora

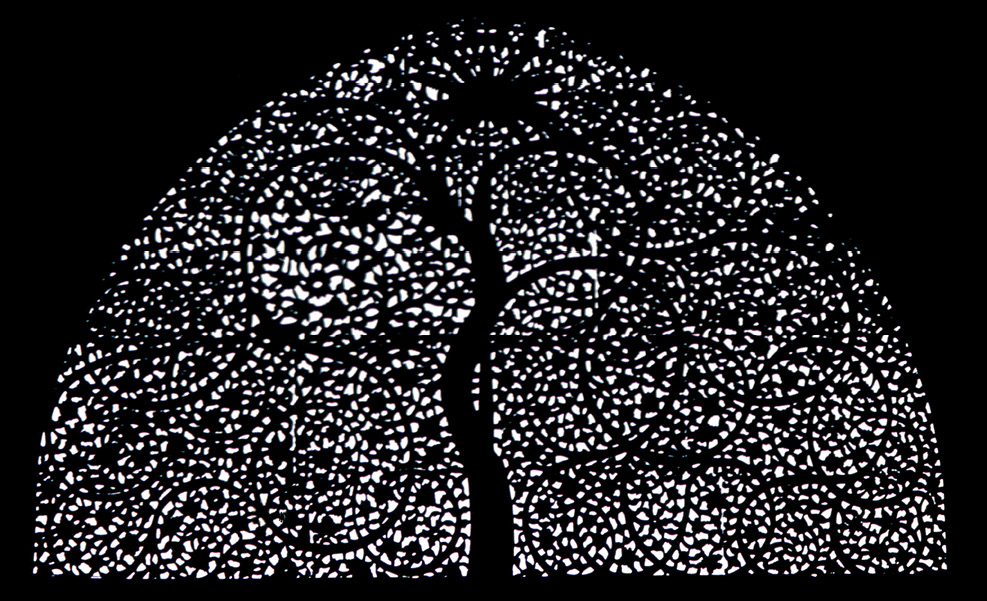

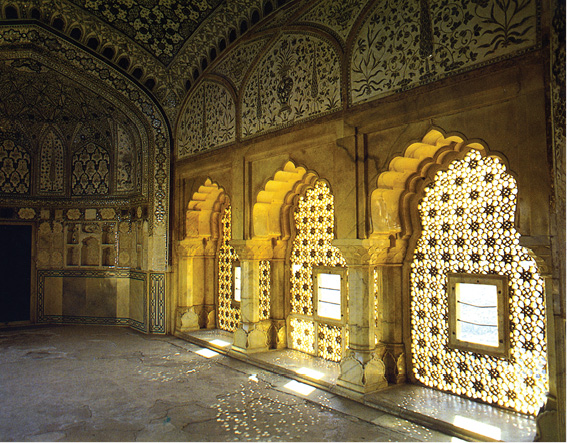

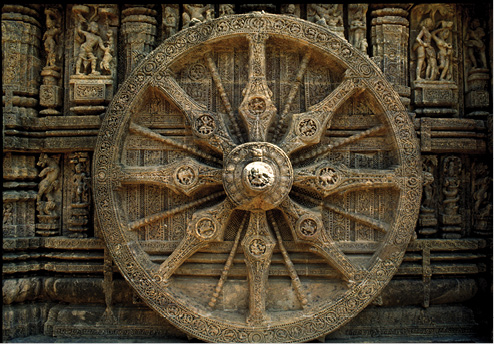

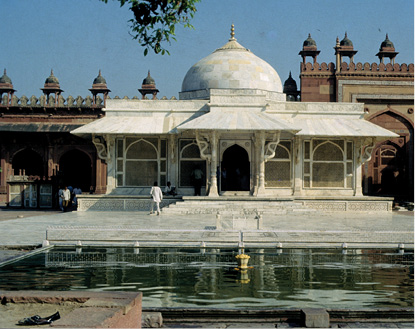

Sandstone panels with geometric and floral design were made to decorate palaces and tombs during the medieval period. The Mughals in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries built some of the most beautiful buildings in the world like the Taj Mahal in Agra. The sculptural decorations are of many varieties — marble jalis are made out of a single slab of stone that is cut to create a lattice window that allows for light and ventilation.

Marble carving, Taj Mahal

To make inlay marble or sandstone panels the artist has to carve out the design in the form of compartments on the flat stone slab. Then precious and semi-precious stones are cut into exact pieces of the pattern and laid into the compartments. The inlay work in the Taj Mahal is so extraordinary that over twenty pieces of different coloured stones were used to create a single flower.

Stoneware

Rajasthan is famous for delicate jali work, for domestic architecture in yellow and pink limestone and white marble. Jaipur also produces stone figurines.

In Madhya Pradesh the soft marble rocks of Bhedaghat on the banks of the Narmada provide craftsmen with excellent raw material to make carved panels, figurines and boxes.

The sculptors of Karnataka carve images, panels of gods and goddesses, ornaments, bowls, vases, and book-ends from a variety of stones available in this State.

Uttar Pradesh is one of the leading producers and exporters of stoneware in India. Soft marble and soft streaked Gorahari stone of many shades are inlaid with semi-precious stones. Inlaid table tops, plates and decorative items are produced in Agra.

In Orissa the stone cutters of Puri work mainly in soapstone. Harder stone is used for temple building. Traditional stone carvers in Mangalpur make stone utensils from semi-hard grey stone and add to it a beautiful polish. Grey stone from Khichling are made into items for the urban market, like boxes and containers, bowls and vases.

Tamil Nadu: Famous stone sculpture centres have been established in many places such as Mahabalipuram, where a training school has trained a number of young artists in traditional stone-carving techniques and in making statues.

Patrons of Crafts

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy in his book entitled The Indian Craftsman describes the craftsmen of India and Sri Lanka that he had studied in the early twentieth century. He divided crafts communities into the following categories.

♦ Those who lived and worked in the village

♦ Those who travelled from village to village and towns

♦ Those who lived and worked in towns

♦ Craftsmen who were employed by the ruler in royal workshops.

Detail of an ornate pillar in a landlord’s house, Chettinad, Tamil Nadu

The Village: The potter, carpenter, stone sculptor, mason and goldsmith lived and worked often in their own homes in designated parts of the village. Everyone in the village knew their local craftsmen and therefore he had no need to autograph his works. The jajmani system ensured that hereditary artisans were bound to the dominant agricultural groups through traditional ties. This was a hierarchical and symbiotic relationship, in which the artists worked under the protection and hospitality of the landowning class. When there was a festival, the landowner or the jajman would request the potter to make ceremonial pots and diyas and in return pay him in kind with food for the rest of the year. When his household needed a grinding stone, the stone cutter would make one to the specified requirement and size.

Itinerant Craftsmen: Some artisans like the blacksmith even today are itinerant craftsmen who move from village to village servicing the community and spending as much time as is required in each place. These crafts communities were often paid in kind with gifts of grain and food, clothing and money so that they did not have to cultivate land for food but could pursue their craft to perfection.

In the Town: While the artists in the village worked as a family, individual artists in the towns formed guilds to protect their interests and to ensure the quality of their work. The guild protected the group and its occupational interests, punishing the wrong doer, negotiating prices and enforcing standards of work. The artist in the town was also paid in kind and with land grants or produce from land.

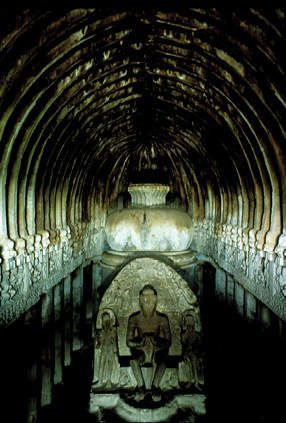

Much of India’s architectural heritage, like the Ajanta caves, was created by artisans’ guilds.

In the Court: Through the ages rulers tried to attract well-known performing artists and craftsmen like sculptors to work in their court. It is the creations of such artists that provide an idea of cultures and eras gone by. Rulers understood that having brilliant architects and sculptors would enhance their empire in many ways. They knew that the creation of magnificent buildings, shrines and sculptures would carry the message of their grandeur to distant places and countries. This is why there are many royal records of grants and gifts to artists who excelled in their work.

The artist who attached himself to the court found employment in the royal workshops and was often a privileged person, given payment for an assignment not only in kind but also in land. The Jetavanarama Sanskrit inscription (first half of the ninth century) of a Buddhist monastery records that:

There shall be clever stone-cutters and skilled carpenters in the village devoted to the work of temple renewal. They all… shall be experts in their respective work. To each of them shall be given one-and-a-half kiri (in sowing extent) for their maintenance… an enclosed piece of land. And one hena (or a plot of dry land) shall be granted to each of them for purposes of sowing fine grain.

– Ananda K.Coomaraswamy, The Indian Craftsman

Emperor Akbar’s royal diary records that payment was given to artists for their work and special awards for excellence were given on pleasing the emperor with the creation of a rare object.

The practice of gathering skilled artisans in the palace workshops and homes of rich landlords continued right into the nineteenth century.

Chaitya Prayer Hall, Ajanta, Maharashtra

In the east the princes and great nobles and wealthy gentry, who are the chief patrons of these grand fabrics, collect together in their houses and palaces all who gain reputation for special skill in their manufacture. These men receive a fixed salary and daily rations, and are so little hurried in their work that they have plenty of time to execute private orders also.

– George C.M. Birdwood, Industrial Arts of India

Who are the patrons of stone artists today? Is there a difference in how they are paid in rural areas and urban centres? Is there any recognition of their work? What are the problems that craft communities face today? These are some of the questions that have to be asked to understand the health of the crafts sector in India.

Tomb of Salim Chisti in marble commissioned by Akbar, Fatehpur Sikri, Agra

Growing Up as an Artist

Living and growing up in a family of artists enables a young child to acquire skills and sensibilities from his/her parents and grandparents. The child growing up in a potter’s home knows how to mix clay from childhood and is sensitive and familiar with the qualities of clay, knowing, for example, by its scent whether it is dry or wet or ready for firing. The sensitivities developed through such familiarity would seem almost natural and effortless.

Critics of Indian art and craft have remarked that Indian artists rarely invented or experimented with tool-making to improve their work, or to develop labour-saving devices. Tools were kept to the minimum, while the process of achieving perfection was as important as the job itself. Skills practised for over 5000 years are still in use in India. Today artists, whether they are stone or wood carvers, potters or weavers, continue to work with the technology and methods used by their forefathers.

In every region of India a distinctive style of architecture developed. Lakshmi Narayan Temple, Chamba, Himachal Pradesh

It appears that once a simple way of making something was developed it lasted for centuries and became the most uncomplicated way of achieving the real goal of crafts. Perhaps finding time-saving devices, effort-saving technologies was not the goal of crafts communities as is illustrated by the experience of a well-known wood carver from Kerala (see box below).

At the turn of the nineteenth century when machines and technical training were overrunning the old system, many scholars like Coomaraswamy wrote about the loss of this parental education and the discontinuity of culture and living craft traditions.

He had studied with his father and has narrated how long and difficult the training was. His family made wooden masks for Krishnattam, an ancient dance–drama of Kerala. He said that as a child he worked with his father–teacher who instructed him on how to carve the mask for the character of Krishna. He used simple tools, the chisel and the hammer, and different types of scrappers. His teacher kept telling him to do it again and again. This went on for seven years! Finally, one day, his teacher looked at his work and saw that his son had captured the ‘idea of Krishna’, the bhava or inner expression of the deity in his wooden mask. Through this lengthy process the son acquired not only mastery over woodcarving but was able to express deep philosophic ideas through his craft.

… for in the East there is traditionally a peculiar relation of devotion between master and pupil, and it is thought that the master’s secret, his real inward method, is best learnt by the pupil in devoted personal service, so we get a beautiful and affectionate relation between the apprentice and the master, which is impossible in the case of the busy professor who attends a class at a Technical school of a few hours a week…

– Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, The Indian Craftsman

Coomaraswamy believed that by living and working with the family the child acquired valuable trade secrets, an understanding of the culture and customs to which they belonged, the rituals and festivals for which their craft was required and the philosophic traditions that transformed their work into art. By attending festivals and rituals, listening to grandmothers’ legends and stories, the child learnt the content of sculptures that he would make later in life. Such an education is not available in technical or art schools of today. It was this guru–shishya and parent–teacher system that led to the continuity and excellence of Indian art.

Contemporary Demands

In Mahabalipuram the sculptors make certain figures which they feel have a demand. They also execute orders received from various organisations, like temples. There is a preponderance of the so-called traditional iconographic forms: gods, goddesses, the elephant god Ganapathy and the whole gamut of religious figurines. The background to this is the College of Traditional Art and Architecture where traditional iconography and architecture is taught. They take on various kinds of contracts for both the local and the export market, especially tombstones for Korea and Japan.

Contemporary pillar base (above) and sculpture (below), Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu

There exists now a burgeoning construction industry almost all over the country. People are demanding more in terms of ‘finish’ to their houses than just plain cement and concrete. They like to beautify houses with objects of art both functional and aesthetic, traditional and modern. Carved stone lends itself to both interior and exterior spaces. It can be used in construction work, objects of art, traditional and modern designs. Stone can be used in a variety of combinations with other materials.

Innovation comes in when there is an active interaction between customer/designer and the craftsman. The craftsman needs to understand the requirements of the client and the customer/designer needs to understand the material, its capabilities and the capacity of the craftsman.

Another important factor is cost. The craftsman would obviously like to make and sell something that can be made as cheaply as possible and sold as dearly as possible. It is important that the price worked out should be such that the craftsman gets the maximum benefit at an affordable cost to the client. A simple example would be carved pillars for a portico. A range of styles should be available from simple columns to carved ones so that they can suit the taste and budget of the client.

EXERCISE

1. What are the inherent qualities of stone as compared to clay? How do such qualities determine the techniques that can be used on one material and not on the other?

2. Compare the patronage structure of the past with the present. How does this affect the objects created?

3. Igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic are different varieties of stone, each having its own properties. How does the craftsman use these properties to advantage in his craft? (Example: Granite, because of its hardness, has been used to create temples of lasting value in Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu.)

4. Coomaraswamy makes a distinction between classroom learning and apprenticeship with a traditional craftsperson. Compare your practical work in the field with crafts communities with your experience of classroom teaching. Do you agree with Coomaraswamy’s views?

5. What do you think are the occupational health hazards and environmental concerns around the use of stone in crafts and buildings?

6. The boom in the construction industry, with every middle-class house boasting of marble floors and granite counters, has led to depletion of stone resources. Draft a Bill or write an article for the local newspaper keeping in mind the following:

- protecting forest lands from quarrying and mining

- protecting the rights of the craftsmen to access the stone

- suggesting alternative materials to replace stone in buildings.