Table of Contents

4

Metal

At the time of Dussehra, Kullu valley comes alive with the arrival of many mohras (metal plaques of Durga) from different parts of Himachal Pradesh. These gold and silver masks were commissioned by the kings in ancient times. Each village brings its mohra from its local temple to Kullu in a decorated palki (palanquin). The mohras are then moved into a huge wooden rath that is pulled by hundreds of devotees. At the time of Dussehra you can see processions of these raths as they weave down the mountain. Musicians accompany each of the processions and the whole Kullu valley fills with the sound of their long metallic pipes.

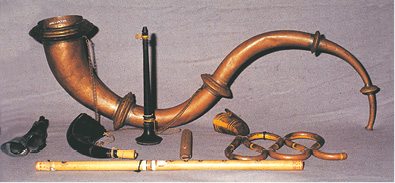

Wind instruments, Himachal Pradesh

There are a variety of pipes, long telescopic ones known as shanal or karnal and the ‘S’-shaped curved trumpet known as narasingha. These are made by local metal-smiths who are often attached to the temple.

The Role of the Blacksmith

Metal craft is one of the most vital traditions of Himachal Pradesh. Here blacksmiths, carpenters and stone workers consider themselves a single group. While they maintain their occupational distinctions, they frequently intermarry. Carpenters and metalsmiths call themselves Dhimans and trace their origins back to Vishwakarma.

Blacksmiths are the largest craft group in Himachal villages and, like all other artisans, they are largely employed as farm labour. They are also traders who sell their products. Like many crafts communities in India, their workshops are in their homes. In Himachal the blacksmiths usually work from their workshops located on the ground floor of their homes.

In any village in the world, the blacksmith’s importance springs from the fact that he is indispensable. The lohar (blacksmith) makes and mends the agricultural implements that are made of iron and also fashions utensils with material provided by the customers. In addition, he also makes tools for other artisans, creates icons and ornaments, and repairs damaged metal objects. His payment usually comes in the traditional way — he receives a share of the produce.

Inside the Metal Worker’s Studio

The wheelwright was also the blacksmith and the tinker of our locality. He and his apprentices did all sorts of odd jobs — plumbing, carpentry, cabinet-making, forging pots and pans, overhauling carriages and carts, repairing boats and barges and a hundred other things. The things that he did not undertake would make a shorter list than those he did.

Inside a metal worker’s studio

We could not imagine a wizard’s cavern more fascinating than our wheelwright’s workshop. Its furnaces, big one and some smaller ones, were a great attraction. What interested us most about these furnaces was the intense glow the coal gave when the bellows worked. It was also engrossing to watch the red hot metal bars hammered into shape. Cascades of sparks flew as from a fountain of fire. It was like fireworks at the Diwali festival! It took our breath away to see the bullocks shod with iron hoofs and the cartwheels fitted with iron bands and then dipped into water. How the sizzling steam came out — vapour coloured by the light of the furnaces!

– Sudhin N.Ghose, And Gazelles Leaping

Patrons of Metal Craft

The patronage of the temple and royal court gave rise to highly accomplished craftspersons, one generation following another practising the same skill for centuries.

Mohras are fashioned out of ashtadhatu,an alloy of eight metals — gold, silver, brass, iron, tin, mercury, copper and zinc.

As time went by, temple and rural art traditions came closer together. Innumerable bronze figurines cast by rural metalsmiths can be seen in village shrines and in home altars even today. These images appear to be timeless.

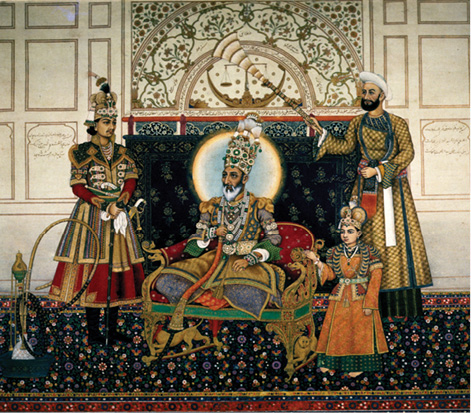

For our traditional rulers, the nobility and wealthy landowners, objects made of precious metal were symbolic manifestations of power. Much of their income from taxes was converted into treasure (khazana) in the form of objects made from precious metals and jewellery. It was in workshops (karkhanas) that goldsmiths and silversmiths, whether private or public servants, practised their skills under the patronage and close supervision of their masters. Some of these objects were made to be presented as gifts on special occasions such as the public assemblies (durbars) that formed part of court ritual, while others were only brought out for specific religious rituals. Still others were designed for everyday use.

The Himachal State Handicrafts Corporation has established metal craft training centres all over the State to impart training in bronze casting and all metal craft techniques.

Less well off zamindars followed the example set by the court. Even the rural population, with little money at its disposal, copied the customs of their superiors. Whatever surplus earnings they had was invested by them in silver ornaments worn by women daily. These proclaimed the wearer’s social and economic status like the beautifully attired women of Rajasthan.

Durbar of Bahadur Shah Zafar

Gold Coins, Gupta Period

Did you know that...

For 11,000 years human beings have been fashioning metal for their use.

♦ Ore metals are the source of most metals. First the ores are mined or quarried from beneath the earth, or dredged from lakes and rivers, then they are crushed and separated, and finally they are refined and smelted to produce metal.

♦ By 5000 BCE copper was used to make beads and pins. By 3000 BCE tin was added to copper to produce bronze, a harder metal. Iron, even harder than bronze, was widely produced by 500 BCE.

♦ The technology of how to master metals (copper, bronze, iron) developed independently in various parts of the world.

♦ By 3000 BCE, most of the gold extracting techniques used today were already known in Egypt.

♦ The concept of carats indicates the amount of gold in gold! Nowadays copper and silver are often added to gold to make it harder. The gold content in this is known as carats.

♦ More than half of the gold mined with so much labour, returns to the earth—buried in bank vaults!

Crafting Metals

Human cultures around the world have a long history of experimentation and expression using alloys like brass and bronze, and precious metals like gold and silver, and in more recent human history using iron and steel.

We have created countless objects from different metals, from tiny coins to buildings, pots and pans to timeless images of gods and goddesses.

Materials and Processes

Other than silver, the metals used in our country for craftwork are brass, copper and bell-metal. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, bell-metal is a mixture of copper and tin.

Soldering is used to join two parts of an article when it is manufactured in more than one piece. Joining together is done by using a metal alloy which the artisan prepares.

The shaping of an object is done either by beating the ingot or sheet metal to the approximate shape with a hammer while it is hot, or by pouring the molten metal in a mould that is made of clay for ordinary ware and of wax for more delicate objects. The beating process is preferred particularly for bell-metal and copperware as it is supposed to make the object more durable. Further, tempering is done by heating the article till it is red-hot, and then dipping it in cold water. If it turns black in this process, light hammering rectifies it.

Commonly used traditional metal vessels

The Lost Wax Process

The lost wax process is a specific technique used for making objects of metal. In our country it is found in Himachal Pradesh, Orissa, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal. In each region, a slightly different technique is used.

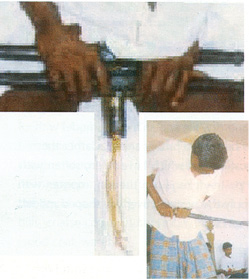

1. The lost wax process involves several different steps. First a wax model of the image is made by hand. This is made of pure beeswax that has first been melted over an open fire, and then strained through a fine cloth into a basin of cold water. Here it resolidifies immediately. It is then pressed through a pichki or pharni — which squeezes the wax into noodle-like shape. These wax wires are then wound around to the shape of the entire image.

2. The image is now covered with a thick coating of paste, made of equal parts of clay, sand and cow-dung. Into an opening on one side, a clay pot is fixed. In this the molten metal is poured. The weight of the metal to be used is ten times that of wax. (The wax is weighed before starting the entire process.) This metal is largely scrap metal from broken pots and pans.

3. While the molten metal is poured in the clay pot, the clay-plastered model is exposed to firing. As the wax inside melts, the metal flows down the channel and takes on the shape of the wax image. The firing process is carried out almost like a religious ritual and all the steps take place in dead silence. The image is later chiselled with files to smoothen it and give it a finish. Casting a bronze image is a painstaking task and demands a high degree of skill.

Making of a Bronze Image

In ritual items made of bronze the best is statuary which represents the visible forms of the deity to be worshipped. For this the Shilpa Shastra’s elaborate treatise is faithfully followed. From the Rig Vedic times there have been references to two casting processes, solid and hollow, termed ‘ghana’ and ‘sushira’. While the images are countless, each is very individualistic, and the craftsman has to learn not only the physical measurements of the right proportions to make the images but also familiarise himself with the verses describing each deity, its characteristics, symbolism and above all the aesthetics. These verses are known as ‘dhyana’, which means meditation. This is to convey the need for intense concentration on these instructions.

Govind Jhara, a metalsmith from Raigadh, sitting before his primitive kiln, starts his metal casting with a little prayer:

Ao Dai (Come, Devi, sit with me)

Andhe ko chaku dani (To the blind give the seeing eye)

While the tradition is there to preserve the core of our heritage, obviously the craftsman is expected to do much more than merely put the limbs together; he has to endow them with the character each image has to convey from out of his own emotions, thoughts and volitions.

To give guidance in modelling each of the important parts of the body, it is likened to some object from nature: eye-brows modelled after the neem leaf or a fish; nose, the sesame flower; the upper lip, a bow; chin, a mango stone; neck, the conch shell; thigh, the banana tree-trunk; knee-cap, a crab; ear; the lily, and so on.

Icon-making is still a laborious and time-consuming job which requires a lot of concentration and demands a formidable array of tools, extreme skill and precision. Usually a coconut palm-leaf is used for marking out the relative measurements for the icon with marks made by folding the leaf. When the mould is broken, care is taken to see that the head of the icon is removed first as a good omen.

Chola Bronze, Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu is one of the famous bronze-casting regions. Stylistically, the images belong to different periods like Pallava, Chola, Pandyan and Nayaka and the images that are now produced belong to one or the other of these styles. The icon- makers are known as stapatis.

– Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay,

The Glory of Indian Handicrafts

Silver

According to Hindu tradition, if objects made of gold and silver become ritually polluted, they can be restored to purity by the simple act of washing them in water or scouring them with ash or sand. It was believed, for example, that water is automatically purified when placed in a gold or silver container. In the case of silver, this theory has been scientifically validated and we now know that the ionic reaction of silver with water does have the effect of killing its bacterial content.

Even though silver occurs rarely in its pure and natural state in India, it has always been widely available. Then where did it come from? The answer—through 2000 years of trade. While we exported spices, dyes, textiles, diamonds and other luxury goods in both raw and finished forms to the Mediterranean, East Africa, the Arabian seaboard, the Red-Sea and the Persian Gulf, the islands of the Indonesian archipelago and even China and Japan, our main import has always been precious metals.

Contemporary studies show that through centuries of accumulation followed by recent import (through both legal and illegal channels!) the people and temples of India possess more than four billion (4,000,000,000) ounces of refined silver! This staggering figure is only a conservative estimate.

As silver has always been 15–23 times cheaper than gold, it lies within the reach of a much broader section of our society.

Utility items in metal

from different parts of India,

eighteenth–nineteenth centuries

Metal Craft Across India

In the Kinnaur District of Himachal Pradesh, the metal objects used for religious purposes are a unique synthesis of Hindu and Buddhist designs. The thunderbolt or vajra motif is commonly seen on kettles and jars. Fruit bowls with a silver or brass stand designed like a lotus, prayer wheels inscribed with the ‘om mani padme hum’ mantra, conch trumpets, miniature shrines and flasks are also made. Many of these forms come from ritual objects used in Tibetan Buddhist temples which are located next to Hindu temples all over Kinnaur.

Teamwork is essential in the craft of metal-work. In Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh for example, the production of an enamelled hookah base would involve several different specialised skills, each practised by a different craftsman. A sunar makes the object; a chitrakar or nakashiwalla marks out the surface design; a chatera chisels away the depression in the design needed to hold the enamel; a minakar carries out the actual enamelling; a jilasaz polishes the object; a mulamasaz might gild it, while a kundanaz sets the stones required in the design. Successful teamwork of this sort clearly relies on a strong underlying design concept and a high degree of stylistic coherence, as well as a feeling of technical harmony amongst those responsible for each stage of the process.

Koftgari is the term for a type of silver and gold damascene work produced in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, Jaipur, Rajasthan, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh and Punjab. In ordinary damascene (tar-i-nishan), a technique used frequently to adorn the blades of swords, a chiselled groove is first made into which precious metal wire is hammered. The koftgari process is simpler and less time consuming, and allows for much freer decoration. The entire surface of the object is first chiselled in at least two different directions so as to roughen it and then the wire (either silver or gold or both) is hammered onto it in intricate patterns. ‘True’ damasceners looked down on this method, but it is simply an alternative process. Once the manufacture of arms and armour had ceased, craftsmen began to apply this decorative technique to trays, boxes and other objects.

Bidri, a technique named after its place of origin, Bidar, Andhra Pradesh, is the application of inlay (mainly silver) to objects cast in a relatively soft alloy of zinc, copper and lead. After the inlay work is completed, the ground is stained black using chemicals, thus creating a splendid contrast to the silver decoration.

In Kerala to make the uruli (wide-mouthed cooking vessel, with flat or curved rims) the lost wax process is used. A giant cauldron called varpu, which is magnificent in form, is used in temples for making prasad to feed thousands of devotees. Kerala also has a great tradition in making metal tumblers for drinking, which range in size and are very elegantly shaped.

Among the numerous ritualistic articles made of metal in Gujarat are large temple-bells. The famous temple-bell on the Girnar Hill weighs 240 kg. Another popular item is the typical low square stool and low arm chairs. This pure metal furniture was highly ornamented in a variety of styles and was used by royalty.

Nachiarkoil in Thanjavar District of Tamil Nadu is an important bell-metal centre. This is due to the presence of light brown sand called vandal on the banks of the Cauvery, ideally suited for making moulds. Some of the articles made by casting are vases in different shapes, tumblers, water-containers, plain and decorated ornamental spittoons which are a speciality of this place, food-cases, bells, candle-stands, kerosene lamps, picnic carriers, and a large variety of oil lamps.

No other country has such imagery and symbolism built around lamps as India. As a symbol of Agni, the fire-god, lamps are auspicious and used at marriages, and also to welcome important guests. Lamps are found in many different forms often with a handle attached to a small tray, shaped as a cobra, fish or swan. These vary in size from little ones for quiet personal worship, to large pedestal ones to light a spacious hall.

1. The metal worker’s craft is indispensable in India. List their contributions in different sectors like agriculture, construction, transportation etc.

2. Refer to a national newspaper and record the prevailing rates of gold and silver. Plot a graph showing the price fluctuation of these metals over a fortnight/month. What factors do you think contribute to this fluctuation?

3. Traditionally, metal objects were sold by weight and the cost of workmanship was not taken into consideration for deciding the price. In the West the cost of workmanship is often greater than the value of the material. In your opinion how should the price of an object be determined? Give reasons to support your argument.

4. Looking at the map page of this chapter, create a table listing reasons why various metal work techniques are used in different parts of the country (see following example). Define precisely each one of the processes. In your own region find out which of these techniques are used in working with metals.

| Region | Technique | Process |

| Himachal Pradesh | Repoussé | A thin metal sheet is placed on a carved wooden block and hammered so that the design appears clearly on the metal sheet. |

6. Sudhin Ghosh’s passage explains the crucial role that fire plays in metal crafts. What measures can you suggest to reduce fire and smoke related hazards?

7. In several religions, precious and semi-precious metal objects are used. Find out what these are and who makes them.