Table of Contents

5

JEWELLERY

All of us enjoy decorating our bodies. In ancient times it was believed that besides enhancing its beauty, decorating the body gave it additional strength and power. Even today many tribal societies use flowers, wild berries, leaves and feathers for this purpose. Flowers and fruits celebrate nature and growth while feathers are valued for their colour and for the power of flight. Seeds, even wings of insects such as colourful beetle wings are used as embellishment and decoration.

One of the oldest forms used in jewellery was that of a sphere, representing the seed, the bija. Later a range of beads were made from clay, glass, metals and precious stones. This symbolised fertility, growth and the origin of life.

Many jewellery forms made in metal reproduce forms of flowers and fruits. Champakali is a necklace made of jasmine bud motifs and is worn throughout India. Karanphul jhumka is a combination of the form of an open lotus at the ear lobe and a suspended half open bud. Mangai mala is a rich necklace from Tamil Nadu, with stylised mango forms studded with rubies. Precious metals such as gold and silver were for the rich while the less affluent used even brass and white metal. Gold was associated with the sun, and silver, chandi, with chandrama — the moon.

In the past when there was discrimination on the basis of caste, only the upper castes were allowed to wear gold. This is now changing and those who can afford it, wear gold and precious jewels.

Strings made of different types of seeds

Meaning and Significance of Jewellery

In some tribal societies, each ornament was a symbol of the rank and status of the wearer, and it was also believed to have certain magical powers. Thus, the purpose of ornamentation was not only to satisfy an instinctive desire to decorate the body, it was also invested with symbolic significance. This aspect is clearly expressed in the form of amulets which carry inscribed prayers to protect the wearer from evil influences. All communities and faiths use this form of jewellery as protection against harm or to activate certain positive qualities.

Streedhan: From Vedic times onwards, jewellery was counted as a woman’s wealth and comprised a part of her inheritance from her father, as well as a gift from her husband.

It was with the establishment of a settled agrarian society that jewellery became a form of saving and a symbol of status. A variety of designs in folk jewellery evolved over the years, and the important position of the jeweller in village society also points to the fact that jewellery was considered as the only form of investment which could be encashed during an emergency.

It was mandatory for married women to wear jewellery. Necklace, earrings, head ornaments and bangles were essential for every married woman. It was only widows who were deprived of jewellery.

Jewellery for Every Part of the Body

Each region in India has a particular style of jewellery that is quite distinct. Differences occur even as one goes from one village to another.

Despite the variety in jewellery patterns in different parts of the country, the designs in each region are also at times strikingly similar.

Ornaments worn by a Bhartanatyam dancer

Head and Forehead: Women wear the bore resting upon the parting of the hair in Rajasthan and parts of Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, whereas the tikka, a rounded pendant at the end of a long chain which falls on the forehead, is used throughout India. The shringar patti which frames the face and often connects with the tikka on the top and the earrings are also used widely. In earlier times men wore the kalgi, a plumed jewel, on top of the turban.

Nose: The ornament worn all over India has variations from the simple lavang, clove, to phuli, the elaborately worked stud, or nath, the nose-ring worn in the right nostril, and the bulli, the nose ring worn in the centre just over the lips.

Neck: One of the ornaments is the guluband, which is made up of either beads or rectangular pieces of metal, strung together with the help of threads. A ribbon is attached at the back to protect the neck of the wearer. Then there is the longer kanthi or the bajaithi. Below this is worn either a silver chain or a necklace of beads. The men would wear a charm or a tawiz at the neck and a kantha, a long necklace.

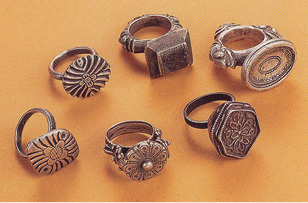

Fingers: For the hands there are a number of rings. On festive occasions women wear the hathphool or ratthan-chowk to decorate the back of the hand.

Wrists: For the wrists there is the kada, the paunchi, the gajra and the chuda, which quite often extends six inches above the wrist.

Arms: The bazoo, the joshan, and the bank are worn above the elbow. Men wore a heavy kada or bangle.

Hips: A series of silver chains formed into a belt are worn at the hips and are generally known as kandora or kardhani, while the men would wear a silver or gold belt.

Ankles: Solid, heavy metal anklets combine with the delicately worked paizebs ending in tinkling, silver, hollow bells, while men would wear a heavy silver anklet. Only royalty wore gold on their feet.

Toes: The bichhua, scorpion ring, for the toe is put on by women at the time of their marriage.

Jewellery for various parts of the body

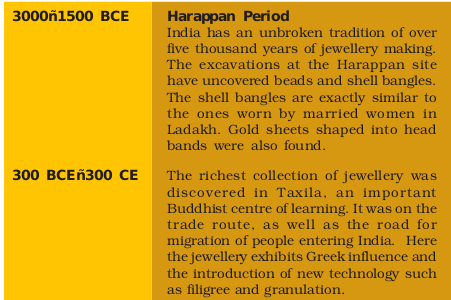

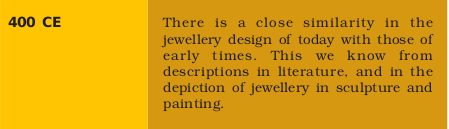

Jewellery through the Ages

About 26 per cent of India’s exports comprise gems and jewels.

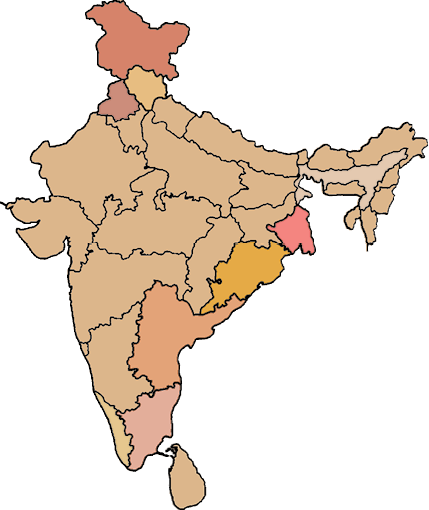

Regional Varieties of Jewellery

Despite the fact that styles in jewellery have, on the whole, tended to develop region-wise, we find that certain distinctive forms have been developed by specific sections, groups or areas.

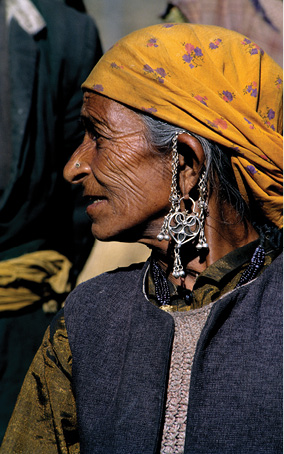

The jewellery of Kashmir is quite distinct. The most important are the ear ornaments, known as kan-balle, worn by Muslim women on both sides of the head. They comprise a number of rings, which are attached to the hair or the cap. This jewellery is also worn in Ladakh and other Himalayan areas such as Lahaul, Spiti, and Kinnaur.

Though all the hill jewellery of Kullu and Kinnaur Districts is made in Hoshiarpur in Himachal Pradesh, it has its own particular style. The pipal patra, made out of bunches of heart-shaped silver leaves fastened to an enamelled piece of silver, is worn in these areas by women on both sides of their caps. It frames their faces with the light shimmering in cascades of silver. Their necklaces are formed out of large metal plates, engraved with the traditional designs of the region and filled with green and yellow enamel. The most common design is of Devi riding her lion.

The nose ornaments of Kullu are also highly specialised. The large-sized nath and boulak designs of a single leaf are not to be seen in any other part of India. On festive occasions they wear a large nath, often larger than the face of the wearer.

In Punjab, women wear a special ornament, chonk. It is cone-shaped and is worn at the top of the head with two smaller cones, known as phul, worn at the sides.

In Assam the tribes patronise silver jewellery, while in the plains gold jewellery is preferred. The patterns of gold jewellery are extremely delicate. The jewels, though few, are finely finished. The earring, known as thuria, has the form of a lotus with a heavy stem. The shape reminds one of the traditional kamal earrings mentioned in ancient literature. Thuria is usually made of gold and studded with rubies in the front portion as well as at the back.

In West Bengal, the filigree work on gold and silver jewellery is extremely delicate. The finest pieces of jewellery are the hair ornaments like the tara kanta and the paan kanta — hair pins designed like a star and a betel leaf.

The folk jewellery of Orissa in silver and gold is rich in patterns, forms and designs. The most popular technique is filigree. The traditional filigree work is robust in character and distinct from what is being produced commercially today in Cuttack. Very few head ornaments are worn in Orissa. The accent is on arm jewels, necklaces, nose-rings and anklets, with the finest designs found on nose ornaments. One design known as maurpankhi, is crafted like a peacock with open feathers, made with the processes of granulation, filigree and casting.

In Sambalpur, brass jewellery is common. Bangles in different patterns are polished daily and appear to be made of gold.

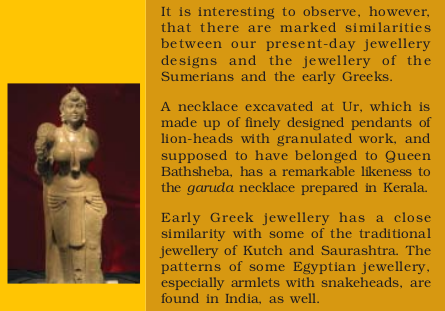

Kerala has a very rich variety of gold designs. The use of precious stones is not so common here. Variety is seen mostly in necklaces. The garuda necklace produced here bears testimony to the fine workmanship of the craftsmen of the area.

In Tamil Nadu, silver filigree armlets worn by Vellalars of Coimbatore District have excellent workmanship in granular work.

Chettinad jewellery, made of uncut rubies, is one of the finest. The addigai is a necklace made of a string of uncut rubies set in gold. A central motif of the padakam imitates the lotus. The mangai-malai is a necklace of mango-shaped pieces studded with uncut rubies and diamonds. The plait cover often has at the top the head of a naga or snake.

The jewellery of the Todas and the Kotas of the Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu, are very distinctive.

Meenakari or Enamel Work

One of the most sophisticated forms of jewellery developed in North India is meenakari. Jaipur is the main centre, but some craftsmen practise this art in Delhi, Lucknow and Varanasi as well.

Meenakari is combined with kundan to produce a delicate and rich effect. The meenakari or enamelled patterns are so fine and intricate that they need to be examined with a magnifying glass. This tradition continues even today.

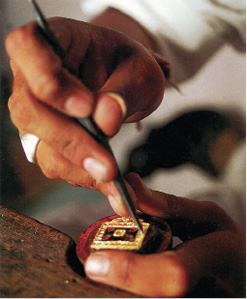

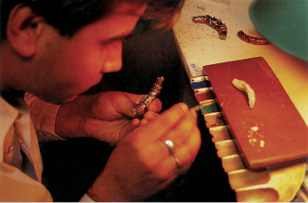

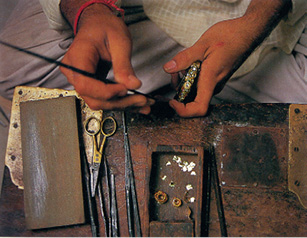

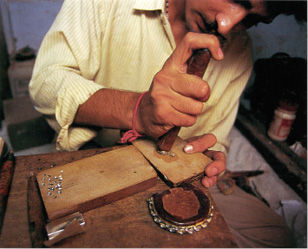

A step-by-step description of how the techniques of meenakari and kundan are combined to make exquisite jewellery is given below.

1. The shape of the jewellery is first created.

2. The jeweller cuts out the sections where precious stones need to be inlaid.

3. It is then handed over to the meenakar who fills the sections with lac, fixes it on a stick of lac, and outlines delicate designs of flowers, foliage and birds.

4. After making the outline, the entire area is engraved for filling the enamel colour.

5. To contain each colour different compartments are created. Within the enclosed, tiny compartments, lines are engraved to hold each colour and also to reflect light, since many of the colours are transparent.

6. After this the colours are filled in and fired in a simple clay oven at maximum temperature.

7. Colours which require a lesser degree of heat are then filled in their respective compartments in the design and fired again, until the whole piece is worked with enamel on both sides.

8. Then the piece is given to the kundan worker, who heats it on warm ashes and fixes the stones in the empty spaces, which had earlier been cut to shape.

9. A fine gold filling, shaped to the size of the opening and intended to hold the gem in place, is then heated and fused to the base of the piece.

10. The finished piece is then polished with a soft leather cloth till it glows.The beauty of the meenakari ornament lies in the combination of elaborate patterns in enamel with the lustre of precious stones.

The uniqueness of the meenakari ornament lies in the fact that even the back of the piece is elaborately decorated, though it will only be seen by the wearer.

The Edge of Tolerance

Following is a poem ‘An Amethyst’ by a school student which depicts the hardships in the life of a gem-cutter.

Uncut amethyst

I am an imported amethyst from Africa

I can see the difficulties of my shaper

His age is 39 years.

And he had been working from the age of eight,

The machine is his own and cost him 250 rupees

It looks to me as if he is being killed by degrees

Shaping an amethyst on a wheel,

With his B.A. degree packed with a seal

Sat Shaldir Ahmad, the stone cutter

He was oppressed but no cry for help could he utter.

Late to bed and early to rise,

He wakes at five and sleeps at 10 o’ clock in the night

Concentrating to shape me, the right size

Due to this process he weakens his eyesight.

This was the work his father Sammu Khan

Had to do

And his grandfather Illahi Achan did the same work,

His children go to a school

He wants them to read and write

And not like him be in a plight.

The labour is one rupee per carat

He gets 1000–2000 rupees in a month

For all his hard work, no part time job he can do

The machine might be his, but the seth owns the Factory.

The uncut amethysts like me are imported,

After being worked at they are exported.

It’s not because the foreign workers are slow,

It’s because the cost of our cut amethysts are low

Because the workers’ pay scale is low.

How hard he works, how little he gets,

How hard he struggles, but, alas! He fails.

This is my tale,

This is my story,

You for yourselves can now

Understand a worker’s sadness and fury.

Bangles and the Bangle-maker

In Firozabad it is a familiar sight to see people on bicycles, wheeling handcarts or cycle rickshaws which are piled high with brightly coloured bangles. They are either being taken to people’s homes for completion or back to the factory for refiring.

Within homes also known as ‘judai addas’, the bangles go through the stages of jhalai, judai and katai. The bangles come in large bunches of 312 bangles, of which 12 bangles are reserved for breakage.

The first stage is jhalai. This work is done by the women and children in the family. Four to five members sit in their one-room house, which serves as their living, sleeping and working area. The roof and the walls of this room are absolutely black with thick soot. The soot comes from the kerosene lamps that are used in their work.

In front of each person are 10 –12 small kerosene oil wick lamps placed in a semi-circle. Each bangle is then held by both ends and the middle is heated over the flame. The heated bangle is then placed on the ground and gently pressed to align the two ends. Care has to be taken to ensure that there are no burns either from the flame or the heated bangle.

These aligned bangles are now taken over by the men or older boys for the next stage which is that of joining the bangle or judai. In this process the two ends of the bangles are heated over a kerosene and acetylene flame. The ends are pressed together and the flame melts the glass enough to join the bangle and make it a complete circle.

In both the stages of jhalai and judai the workers suffer the risk of being burnt besides straining their eyes. Cramps, pain in the joints as well as severe backache are some of the other problems faced by these workers.

The joined bangles are now ready for the katai addas. The carving is done on a fast revolving wheel on which designs are etched into the glass. During this process it is very common for the worker to get cut on the wheel or get flying glass particles into his eye. This is accompanied by aches and pains including a strain on the back.

Gold coating is the next step that the bangles go through. Here a solution of pure gold and chemicals is poured into the designs etched on the bangles, giving them an elaborate look. During this stage the workers handle all the raw chemicals without wearing any protective gloves or aprons.

As the gold solution is very expensive, the workers have to be very careful in handling it, so as to minimise wastage.

The bangles are now sent back to the factory for refiring, which gives them a sheen. These are put individually on a tin tray and placed in a furnace. They have to be pulled out to check and recheck if the process is complete. The workers run the risk of exposure to excessive heat, burns and heat cataract. Finally the bangles are sorted out and packed in boxes.

– Feisal Alkazi, Martha Farell and

Shveta Kalyanwala, ‘The Danger Within’

EXERCISE

1. Designs translate natural forms into symbols. What do you think were the sources of inspiration and symbolism of the following. (Example: Bija or seed represents growth, fertility, prosperity.) (a) Mangai mala, (b) Shikhar of a temple, (c) Dome of a mosque, (d) Wooden tribal pole, (e) Kumbha or pot, (f) Kite.

2. It is said that in Rajasthan a woman carries all her wealth on her body in the form of jewellery. This is one of the ways of investing wealth. What are the other ways of conserving one’s wealth?

3. It is difficult to decide whether it is folk jewellery which has influenced urban jewellery, or vice versa. There is no doubt, however, that many of the forms like the bore, the har, the hathphool, the gajra, originally developed in folk jewellery were later adopted by city jewellers who refined them by using gold and precious stones. Do you agree? Argue your case giving examples of contemporary male and female jewellery fashions in your region.

4. It is interesting, however, to find that children of all castes and communities wear the hasli as it is supposed to protect their collarbone from dislocation. What do children of your community wear and what is the significance of each piece of jewellery?

5. Until recently designs in clothes and jewellery of the people all over India were governed by their particular caste and the community to which they belonged. Do you think this tradition is changing, and why?

6. Investigate the occupational health hazards in different aspects of jewellery production, as for example in meenakari work or in the bangle industry. How can this be addressed?

7. A recent Hollywood film called Blood Diamond describes the political conflict, exploitation of children, and slavery involved in the mining of diamonds in Africa. Write a poem or story on a related theme based on your observation/experience/research.