Table of Contents

8

TEXTILES

Textiles are a part of India’s history — its past, present, and future. Indian textiles were found in the tombs of the Egyptian Pharaohs, they were a sought-after export to ancient Greece and Rome, they also became part of the fashionable attire of both European and Mughal courts. Suppressing and replacing the Indian handloom cotton trade with mill-made alternatives was a key factor of the British Industrial Revolution. That is the reason Gandhi made handspun khadi a symbol of the Indian Independence movement. Even today, millions of craftspeople all over India produce extraordinary traditional textiles that appeal to the international market.

Weaving a Tradition

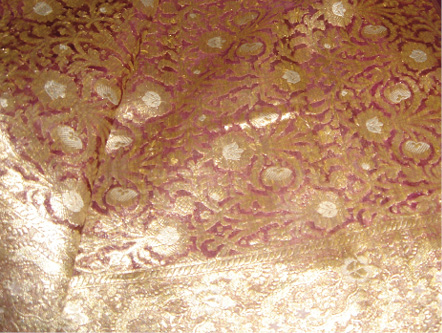

Brocade work, Varanasi

Sathya sat at the big wooden loom, throwing the shuttle through the shining silk threads stretched on its frame. As he wove the warp and weft together, the fabric that unfolded was a Kanjeevaram silk saree, purple and red, with gold tigers, elephants and peacocks dancing together on its resplendent pallav.

The ‘thak-thak’ sound of the shuttle as it moved to and fro had always been part of his life. His father, and his father’s father, and his father’s father’s father, had all woven sarees on the same family loom—as had their forefathers as far back as memory could stretch.

Sathya was 17. He had learnt to weave when he was eight, though he longed to play football with the other village boys. New laws do not allow children below fourteen years of age to work. But everyone in his village was involved in weaving. The women spun the thread, and stretched the warp on the loom. The village dyers and washermen dyed the yarn in wonderful colours, starched, and sized the finished fabric. Traders came to the village from all over India to buy the sarees, while other traders from Surat brought the gold zari thread with which they were woven. The village economy depended on women continuing to wear these traditional sarees for weddings, festivals, and special occasions. Sathya’s father had a picture cut-out from a magazine of a famous film star in one of his sarees.

Sathya’s grandfather was now too frail and blind to weave the intricate sarees. He told Sathya stories of the days, many hundred years ago, when South Indian weavers were one of the richest communities in India. Their wealth built the huge temples and funded royal armies.

Whole communities were known for their weaving skills, and their surnames proudly denoted their trade — Vankars in Gujarat, Ansaris in UP, Mehers in Orissa — just as the Kutchi Khatris were dyers and printers.

Sathya knows that these days even highly skilled weavers are desperately poor, even though their sarees are worn only by the very rich. Weavers depend on traders for loans in order to pay for the expensive silk and gold yarn from which the sarees are woven. Machine-made sarees made in the big industrial mills and cheap synthetic silk copies from China are taking over the market.

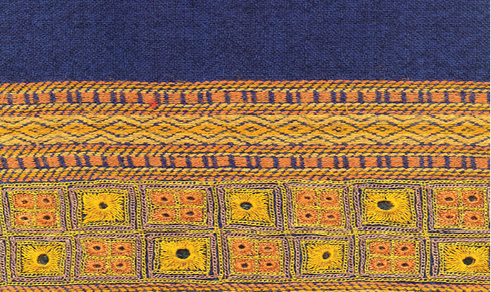

Kanjeevaram saree, Tamil Nadu

Indian hand-crafted textiles are unique today for their variety and beauty. This is a living craft, practised by millions of craftspeople — many in their teens and twenties. No other country in the world has a weaving tradition that goes back thousands of years and is still part of the mainstream economy. Sathya and other young craftspeople like him make India special and proud.

Yarn, Threads and Fibres

In the story about Sathya you read about many aspects of weaving. You came across terms like ‘yarn’, ‘loom’ and ‘shuttle’, ‘warp’ and ‘weft’, ‘starching’ and ‘sizing’, ‘traders’ and ‘weavers’. Some of the fibres commonly used in textile weaving are:

♦ cotton

♦ silk

♦ wool

♦ mixture of the above

♦ gold and silver thread, etc.

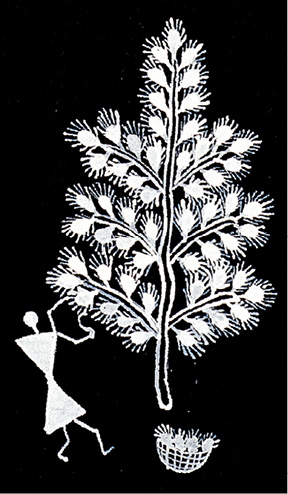

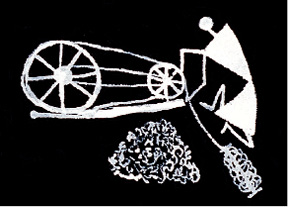

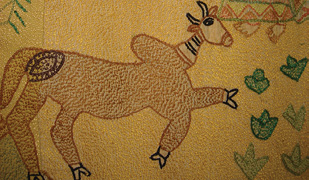

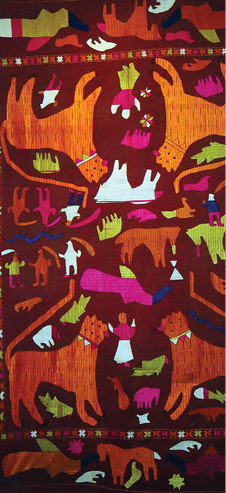

Warli representation of gathering and spinning cotton, Maharashtra

Cotton: It has been cultivated in India since the Harappan Civilisation. Raw cotton is a round fluffy white ball growing on a bush about three feet high. Earth, seeds and other impurities are removed from the cotton balls by ginning. The loose fibres of cotton are collected and bowed with a bow made of canes and the string of the mid-rib of a banana leaf. The vibration of the string fluffs and loosens the cotton. It is spun on a charkha or spinning wheel to the required thickness and texture and is then ready for weaving.

The thread is classified by its thickness: the thinner the thread, the higher the number of counts, and the finer the fabric. Its fineness and its absorption quality make it an ideal fabric for the heat of the Indian summer.

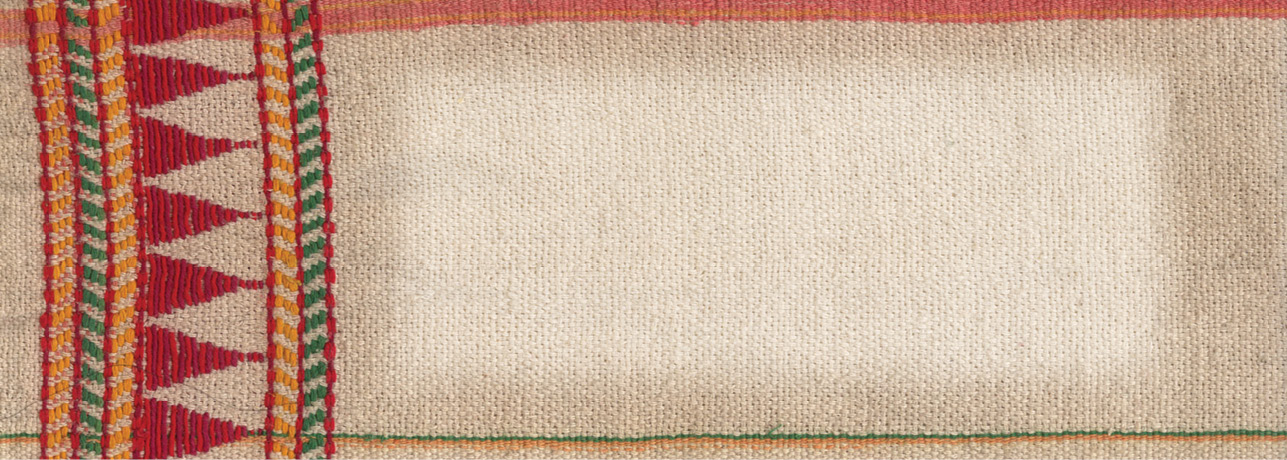

Cotton Shawl, Gujarat

A variety of cotton fabrics were woven all over the country, ranging from course, strong gauzes to the finest of muslins, that represent the highest achievement of the cotton-weaving industry in India.

Indian muslins were used as shrouds for royal Egyptian mummies, and used as garments to adorn Mughal emperors 3000 years later. Delicate muslin cottons were given poetic names like ‘flowing water’ (abrawan), ‘evening dew’ (shabnam), and ‘woven air’ (bafthava), by their court poets. Now they are commissioned by national and international designers!

Silk: It is made from the cocoon of a cream-coloured moth which feeds on the leaves of the mulberry tree. The caterpillar of the silk moth spins an oval cocoon of very fine silk, the size of a pigeon’s egg. The silk is generally yellow, but sometimes white.

Silk cocoon

About 1600 silk worms produce nearly 500 grams of silk and one hectare of land produces enough mulberry leaves to feed caterpillars that can produce 46 kg of silk. It takes about seven days for the cocoon to be fully spun round with silk.

The cocoons are collected and sorted into different qualities and then boiled. The silk thread is reeled and twisted, dried and polished. It is then wound on a spindle and spun. The softness, the lustre and the tensile quality of silk make it one of the most prized materials for weaving fabrics.

Secret of Silk

Some textile traditions came to us from other parts of the world—just as silk came to India from China. According to legend, the Chinese had banned the export of silk worms; however, they were smuggled into India by Chinese Buddhist monks in the hollow shafts of their cane walking sticks.

Mix of Silk and Cotton: Another glorious fabric is mashru, a lustrous weave from Gujarat, patterned in brilliant multi-coloured stripes, or dots as fine as rice grains. Though it appears like silk it is not really silk. Mashru, and himru, have a twisted weave with a silk underside to replicate the look and feel of satin while technically remaining cotton.

Kanjeevaram saree, Tamil Nadu

Tussar, Eri and Moga: India is the only source of tussar silk that comes from the Antheria Assamia moth, which feeds on the leaves of the Som and Wali trees. Tussar silk has a coarse, uneven texture and a slightly yellowish brown colour. Since it is less strong in texture and cannot be refined it does not have the same sheen or fineness as mulberry silk.

Mashru and Himru, Gujarat

Women weavers of Assam make their traditional mekla-chador costumes with golden moga and eri silk, which come from worms that feed on Ashoka and castor leaves rather than mulberry leaves.

Ikat silk saree, Orissa

Wool: It is spun from the fleece of animals. Sheep wool is the most common, but in India goat wool, camel hair, and ibex hair is also used. In North India the angora rabbit is bred for its fine, long, very soft and silky hair. Its warmth, tensile strength and resistance to fire, give this wool its special quality.

The fame of the Kashmiri Jamawar shawl can be gauged from the fact that the English word ‘shawl’ is derived from the Persian ‘shal’—a length of woven woollen fabric. Shawl weaving in Kashmir was introduced by the ruler Zain-ul-Abidin in the fifteenth century bringing in Turkistan weavers to teach the twill tapestry technique to local weavers. As many as fifty colours were used on one shawl.

The rough goat wool dhablas worn by shepherds and camel herders in Kutch and the Thar Desert have been reinvented into wonderful contemporary shawls, home furnishings and throws. Today designers are translating indigenous motifs and colours from tribal shawls of the North-east and Kinnauri shawls of Himachal into softer merino and sheep wool.

Jamawar shawl, Kashmir

The celebrated Kashmiri shahtoosh ‘ring shawl’ made from the fleece of the wild Himalayan ibex is so fine that a metre of this woollen shawl can pass through a man’s signet ring. Production and sale is banned today for ecological reasons and to prevent the extinction of the ibex. Weaving it was a fine art, wearing it now a forbidden luxury.

Woollen shawls from different states of India

Textile Techniques

Indian textiles may be divided into two groups: loom decorated and post-loom decorated fabrics.

Loom-decorated fabric

Loom-decorated fabrics are provided with artistic treatment when on the loom.

Working at a loom

Post-loom decorated fabrics are textiles in which artistic treatment is given after it is woven. In other words, plain textiles are decorated with techniques such as:

♦ dyeing; tie and dye

♦ hand printing; hand painting

♦ embroidery

♦ patchwork and appliqué

Tie and dye

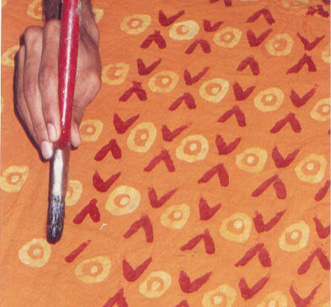

Hand painting

Embroidery

Appliqué

Loom-decorated Fabrics:

In different states of India handloom weaving is done on a variety of looms such as:

♦ throw-shuttle loom

♦ fly-shuttle loom

♦ loin loom

♦ pit loom

♦ jacquard

The art of weaving is governed by three movements — shedding, picking and beating.

The shedding movement consists of moving the treadle with the feet, to make the alternate warp threads open for the shuttle.

Loom decoration of fabrics

The picking movement propels the shuttle to run across to the other side.

The beating movement consists of patting the weft thread into place.

As the process is repeated, the weft thread passes from side to side, over one set of warp threads and under the other. These movements are repeated to produce the basic fabric. Textures are produced by varying the count of the warp threads, and by weaving them tightly or loosely. Patterns can be produced with the introduction of coloured warp and weft threads.

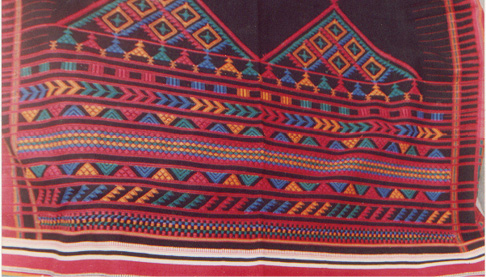

Women of the North-Eastern states weave bold black, red and white cotton shawls with images of shields, swords, butterflies and snakes, using a narrow loin loom which they attach to their waists with straps.

An 80-year-old Manipuri woman wearing a worn handloom shawl was asked whether she was cold and why she did not buy a warm synthetic mill-made sweater that was inexpensive and easily available in the market.

Her reply reminds us of so many intangible things we disregard: “I’ve spun this with my own hands; my mother and sisters have woven it. The warmth of so many fingers has gone into this. How can a machine make anything warmer?”

Block Printing

Block printing, as it is practised all over Western and Central India, is described below.

Each design is printed with a series of different intricately cut wooden blocks.

1. Carving the blocks is itself an art—duta, the block for the outline, gud, for the background, one block for each of the other colours. Some designs have as many as six to eight different colours.

Making a block

Wooden blocks

2. The block is dipped in liquid colour, and pressed firmly onto the specially treated cloth with a little bang of the other hand to make it register evenly.

3. Once the whole cloth has been printed with one block, printing with the next block follows, and then the next, in sequence.

4. Printers have to be careful to place the little marker at the corner of the block to make sure it doesn’t slip and that each colour fits into the design accurately.

Block-printing is a post-loom method of decorating fabric.

Distinctive Designs and Techniques

Like weaves and embroideries, block-print designs and colours have the special stamp of the places from where they originate.

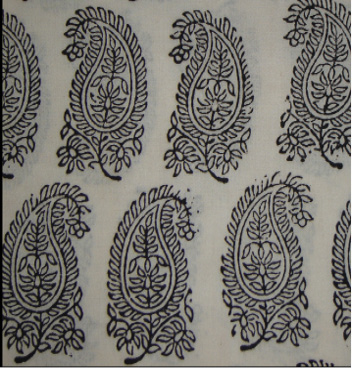

Wooden block of paisley motif

Those from Sanganer in Rajasthan have designs that include delicate floral butis in a range of colours.

Farrukhabad of Uttar Pradesh has all-over paisley jaals.

Bagh prints from Madhya Pradesh are in dramatic red and black.

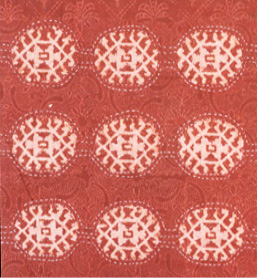

Dhamadka of Kutch is famous for its double-sided ajrak, interlocked hexagonal motifs in shades of indigo, crimson and black, which requires 15 different processes to achieve.

There are also numerous block-printing techniques — direct, resist, batik, discharge,khari chhaap (gold and silver stamping).

In some, the dye is applied directly to the cloth, in others, areas are prevented from getting coloured by the use of wax, mud, or chemicals. Each technique is distinctive.

Printed motifs

Top left: Bagh,

Madhya Pradesh

Bottom left: Dhamadka, Kutch, Gujarat

Top right: Farrukhabad, Uttar Pradesh

Bottom right: Sanganer, Rajasthan

Indian Embroidery

The explorer, Marco Polo, said in the thirteenth century about India: “...embroidery is here produced with more delicacy than anywhere in the world”.

There are shawls from Kashmir that are magically two-sided with the same design embroidered in different colours on each side. This is known as do-rukha. A single shawl may take over two years to complete.

Punjab is famed for its traditional embroidery called phulkari—flowering work. Using threads in brilliant colours like flaming pinks, oranges, mustard yellows and creams, the reverse satin stitch is done on a brick-red khadi cloth. An all-over embroidered shawl (dupatta) is called a bagh, literally resembling a garden of flowers.

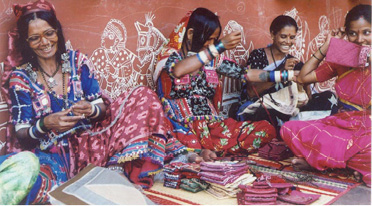

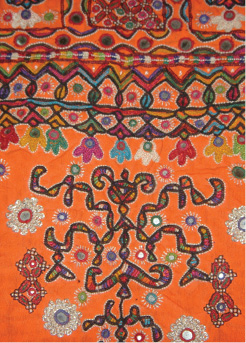

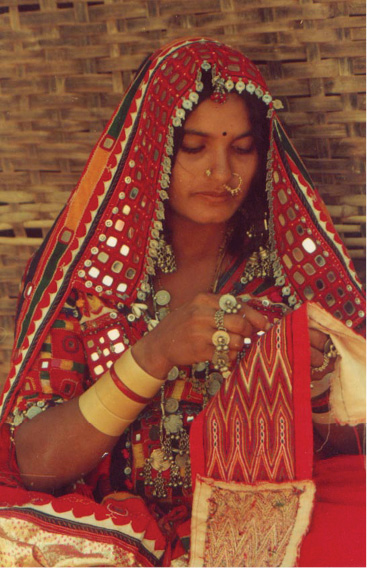

In Kutch in Western India, the women, whether Rabari, Ahir, Mochi, Meghwal, Darbar or Jat, learn to embroider from a young age. They embroider their trousseaus—skirts,cholis, veils, quilts, decorative pieces for their homes. Most Kutchi embroideries use wonderful colours — magenta, emerald green, yellow, and purple. As bright as their desert landscape is bleak, their embroideries are exuberant, with designs of flowers, peacocks, elephants and parrots. Each village and community in Kutch has its own distinctive set of stitches and motifs: cross-stitch, satin and herringbone stitch, and a very fine chain stitch done with a hook. Shiny mirrors are stitched onto the fabric.

Sujni, from Bihar, is a form of quilted embroidery with mainly narrative themes.

There are 22 different chikan stitches. Legend has it that Empress Noorjehan inventedchikan while making a cap for her husband, Jehangir. Chikan-work from Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, has many different stitches worked on cotton mull, creating a textured relief of flowers, paisleys and stars. The stitches have wonderful names—ghas-ki-patti as delicate as grass, murri which looks just like a grain of rice, and keel, the tip of a nail. The most common are: bakhia, a herringbone stitch done on the reverse of the material so that the design appears like a shadow, tepchi, a linked running stitch, and phanda, a tight round knot, used to form flowers and leaves.

Kantha, embroidery from Bengal, is made of thousands of fine stitches, giving the fabric a puckered quilted look. In Bangladesh and India kantha was used to make quilts and coverlets. Old sarees were folded together and embroidered with coloured threads pulled from saree borders. Now kantha embroiderers make sarees and dupattas for the metro market.

Patchwork and appliqué are other textile skills practised by women all over India. They range from the tiny geometric patchwork gota done in Rampur and Lucknow, to the bold, vividly patterned pictorial quilts of Rajasthan and Gujarat—each bride was expected to have at least a dozen.

Pipli in Orissa has its own unique form of appliqué—bold red, yellow and green dancing elephants and parrots, outlined with white or black chain-stitch on equally colourful base fabric. It was developed initially to make the rath procession hangings for the Puri Temple, but is now used for garden umbrellas, cushions and for other urban needs.

The Lambani, Lambada and Banjara gypsy tribes from Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka in South India create spectacular embroidery. Like the Kutchhis, they too wear wonderful skirts, backless blouses and veils, covered with vibrant, colourful mirrored designs, silver or metal coins and ornaments at the edges. Their designs are geometric rather than naturalistic flowers, birds and animals.

Kasuti of North Karnataka is a combination of four different stitches, done on the borders, pallav and blouse of the blue-black, indigo-dyed Chandrakala saree, an essential part of the trousseau of Hindu brides of the region. The motifs are pictorial in character: the Tulsi plant, temple chariots, eight-pointed stars, parrots, peacocks, bridal palanquins, cradles, and flowering trees.

Did you know...

♦ Colour is the first thing one notices about India. As Kamladevi Chattopadhyaya has said, every colour has its tradition, emotion, social context and rich significance.

Red, the colour of marriage and love; orange and saffron, the colour of the ochre earth and the yogi who renounces that earth; yellow, the colour of spring, young mango blossoms, of swarms of bees, and of mating birds. Blue, the colour of indigo, also the colour of Krishna, the cowherd child-god…. Even the great gods had their colours — Brahma was red, Shiva was white and Vishnu was blue.

♦ The Vishnudharmottara speaks of five white tones — ivory, jasmine, the August moon, August clouds after rain, and mother-of-pearl.

♦ It is not surprising that by the seventeenth century, William Moorcroft could list over 300 colour shades in use among the shawl makers of Kashmir.

♦ As early as the first century BCE travellers along the Silk Route recorded fabrics in seven shades of brown, four shades of blue, and four shades of green.

♦ In India colours were made of vegetable and mineral materials: pomegranate, lac and madder for the pinks, reds and browns; black from iron castings; myrobalam petals for yellow. Colour was produced from most unlikely sources: onion skins produced a beautiful reddish brown; pistachio shells, green; glowing lacquer red came from a humble beetle. The concentrated urine of cows fed on mango leaves gave a rich orange yellow.

♦ There is a story of a British Raj billiard table baize (cloth used for billiard tables) which was stolen from the Regimental Mess to extract just that exact green required in a Jamawar shawl.

♦ As always, colours, even those derived from mineral sources (silicates and borates of different metallic salts— cobalt oxide, potassium chromate and manganese carbonate) were given poetice names: Ab-e-leher (ripples of water), tote-ka-par (parrot’s wing), khoon-e-kabutar (pigeon’s blood).

Home and the Market

In India, commercial embroidery made for the market was always done by men. Even chikan work was traditionally a male preserve, with women only doing the coarser filling details. The intricate gold wire and sequin work of Uttar Pradesh (zardozi, kamdani and mukesh) done on a stretched wooden frame, and Kashmiri ari, wool crewel work, tilla and sozni embroidery are still almost exclusively a male domain.

Sozni with its intricate detailing of flora and fauna derives its inspiration from the verdant, flowering beauty of the Kashmir valley.

Tilla work is now a major business for wedding costumes, movie costumes and the fashion ramp, and it reflects the glory of the Mughal court that brought gold wire work from the Middle East and Byzantium.

The lives of my family hang on the thread I embroider.

– Ramba Ben, embroidery craftswoman from Banaskantha

Today, rural women embroiderers are finding new empowerment and earning an income from their embroidery skills in the market. All over India, be it Bihar or Banaskantha, women now embroider for a living.

EXERCISE

1. Read the verse by Kabir on page 23 and develop your own poem using images from textile weaving.

2. Look at traditional textiles in your home and develop a table like the following example.

| Origin | Textile | Motif | Meaning |

| Tamil Nadu | Silk | Flower | Life, beauty, auspiciousness |

3. From the farmer who grows the cotton, to the advertising agency that sells the finished product, the textile industry employs thousands of people with specialised skills. Create a profile of each.

4. “The bones of the Indian weaver are bleaching the plains of India,” said William Bentick in 1835. From your understanding of history, describe the impact of colonialism on the Indian textile industry.

5. Consider Gandhiji and khadi and explore reasons why and how the meaning and significance of khadi has changed over the last 100 years.

6. Consider the clothes worn by members of your extended family. Why do they choose to wear what they wear? Think of caste, religion, age, gender, traditions, and fashion as expressed in the materials, headgear, footwear, costs etc.

7. How is your own philosophy of life reflected in the clothes that you choose to wear?

8. Which types of embroidery were traditionally done by men in our country, and why?

9. Research and document the textile traditions of your state.