Table of Contents

10

Theatre crafts

The air was sizzling with the energy of the crowded spectators; children in front, women in a special section, and everyone else crowding in over the palace walls and ledges. The dancing began with an aarti. The music here is sophisticated, as is the style, with the arms moving in beautiful patterns, both geometric and lyrical…

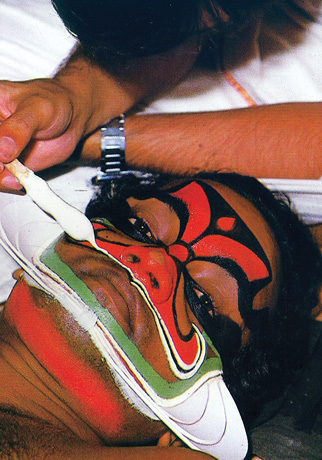

Chhau performance,

West Bengal

The masks are heavy and do not permit the dancers to breathe normally, so after a particularly strenuous piece, the performer flings himself onto the line of attendants, gasping madly. They inevitably collapse like dominoes onto the screaming children, as they frantically rip off their masks. This adds to the strange, unearthly feeling of the evening...

On the fourth night, the dance festival begins at the Kalika Ghat. The dancer wears a black costume and covered in black body paint looks terrifying. He dances his way up in a trance from the river, surrounded by the bhaktas, and comes to the Shiva temple. Outside the temple a brief ceremony takes place in front of a small fire while the dancer sways his body and rolls his eyes.

– Extract from an article on Chhau by Ram Rahman

Story-telling

Everyone loves a good story. We have heard stories from our grandparents, parents, family and friends throughout our childhood.

In India we have invented many ways of telling stories. A few of them are described below.

Glove puppet, Kerala

Puppetry: A puppet is a doll or figure representing a person, animal, object or an idea and is used to tell a story. The puppet is made of various materials and can be moved in different ways. Puppets are classified as follows on the basis of the way they are moved in performance:

♦ string puppets

♦ glove puppets

♦ rod puppets

♦ shadow puppets

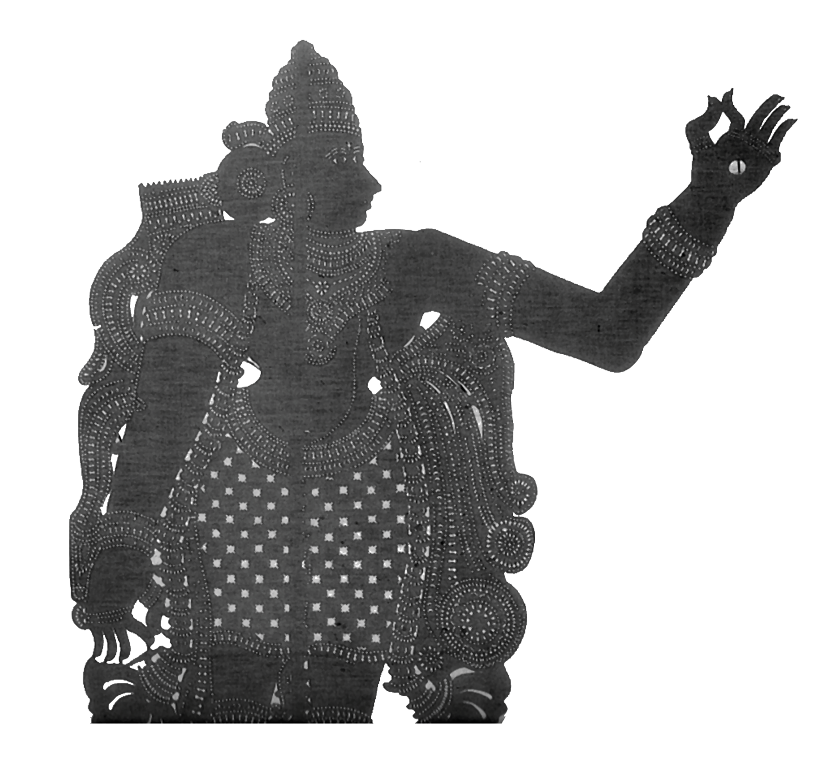

Shadow puppets, Andhra Pradesh

String puppets, Karnataka

Scroll Paintings: There are different kinds of scroll paintings in India. Scroll paintings usually done on cloth are narratives on different social and religious themes. The narrators sing and explain these themes, sometimes accompanied by instrumentalists. Especially famous are the scroll paintings from Rajasthan, West Bengal and Orissa.

Bhopa (narrator), Rajasthan

Theatre: It is a great form for story-telling in which one or more actors using the skills of dancing, acting, singing, talking, miming and theatre crafts like masks, make-up and costumes create a story world for us.

Masks, make-up and costumes

Every corner of India has its own unique form of folk theatre — the lively Nautanki of Uttar Pradesh which often draws on romantic Persian literature for its themes; raw vigour and bawdy humour characterise the Tamasha of Maharashtra or the Bhavai of Gujarat; the blood and thunder of the Jatra melodramas of Bengal which are in great demand during Puja (Dussehra) festivities: or the dance-drama form of Yakshagana from Karnataka, to name just a few.

In this chapter we look at only a few of these to encourage you to look for and discover any similar traditions that exist in your own neighbourhood.

Theatre: a Composite Art Form

Theatre is a composite art form in which many skills, arts and crafts are brought together. A wide range of craft objects are made especially for use in drama, dance or music performances, such as the following:

♦ masks

♦ make-up

♦ head-dresses

♦ costumes

♦ lightweight jewellery

♦ sceneries and stages

♦ music with drums and trumpets, manjiras

Masks

Why did our ancestors use masks, and why are they still being used in several parts of our country?

In many tribal societies across the world, masks still have a ritual significance. People believe that by wearing or putting on a mask, the person ‘becomes’ the character depicted on the mask.

Masks, those magical objects with which we cover our faces and assume a different identity, have a rich and varied tradition in our country.

Kathakali mask, Kerala

From the delicate pastel coloured masks and shimmering head-dresses worn by Chhau dancers to the demon dance masks of the Buddhist monasteries of Ladakh to the inexpensive animal masks of papier-mâché available in our cities, India has a vast and ancient tradition of masks and make-up for rituals and theatre.

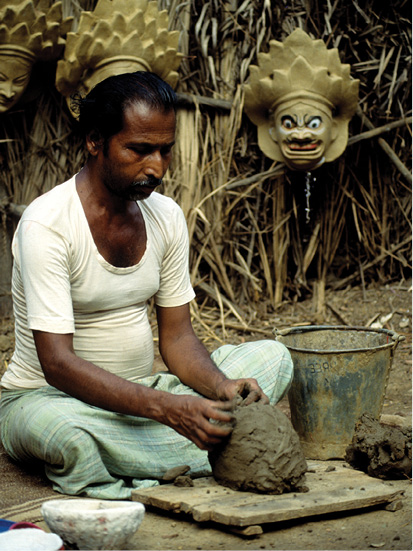

How the Chhau Mask Is Made

The most beautiful masks in our country are made for the Chhau dance form. Chhau is a style performed exclusively by men from the triangular area where Bihar, Bengal and Orissa meet. This is the tribal belt of India — home to the tribal groups of Bhulya, Santhals, Mundas, Hos and Oraons. The masks they use vary depending on the style of Chhau practised — Seraikella Chhau or Purulia Chhau. In the third form of Chhau, Mayurbhanj Chhau, masks are not worn.

The Chhau mask is made of potters’ clay (matti ghada) over which layers of muslin are pasted followed by paper (kagaz chitano). Using a delicate wooden chisel, different features of the mask are polished — the nose, eyes, ears, chin and lips. Once it is dried it is painted in pastel colours (kahij lepa). Then the mask is separated from the clay model and fully dried in the sun. The clay is then reshaped to make another mask. Finally, the mask is worn with a highly decorated head-dress of tinsel, pearls, coloured paper and artificial flowers.

Mask making is a hereditary occupation and mask makers come from Chorinda village in Bengal. Masks are made between February and June as it does not rain at this time, but the fragility of the mask ensures its makers are always in high demand. It is only in Chhau that all the dancers wear masks. The sophistication of technique and expression is most evident when the mask is seen in movement.

Though they appear flat and neutral with their distinguishing features of arched eyebrows and elongated half-closed eyes, the masks acquire a whole range of expression with every twist and turn of the body. Accompanied by the huge dhamsa drums and two energetic dhol players who provoke and encourage the dancers, the Chhau dancer makes lightning body movements known as chamak.

Excavations have revealed small hollow masks dating back to the Indus Valley Civilisation. In fact in Bihar a terracotta mask of the fourth century has also been excavated. The Natya Shastra speaks of masks and their use in theatre. Here it is mentioned that masks can be made of ground paddy husks applied to cloth.

Did you know...

The best known leather puppets in our country are those used in the Tholu Bomalatta of Andhra Pradesh. The origins of these puppets can be traced back to about 2000 BCE, as they are mentioned in the Mahabharata.

Leather puppets are made out of the hides of goat, deer and buffalo. The skin is treated with herbs and oils, and then beaten till it becomes translucent. The different parts of the puppet’s body are separately cut out of this skin. Gods and heroes are made the largest in size, because of their importance. Minute elaborate shapes are punched in the skin to delineate the gorgeous costumes and jewellery of each figure. They are then dyed, according to the different colours assigned to each of them. Carving out the eyes is done last for this symbolises bringing the figures to life.

The angle of the head has significance: a downward glance suggests modesty, a high chin indicates arrogance. Colours too have meaning: giant bullies and their kind have red faces, while white stands for a fiery nature. The pieces are then joined together with a thick knotted string, which facilitates easy movement. A split-bamboo or palm leaf stem is used for the main central support of the puppet. The legs are loosely attached from below the knees, and the manipulator can jerk the puppet to produce the swaying movement of the legs.

The screen for the shadow puppet show is a bamboo box-like stage erected in the open air. In the rural areas, very often, oil lamps made of split coconut shells are used for lighting. The flickering light keeps the puppets in constant movement, and lends an air of magic to the show. Music forms an intrinsic part of the puppet show, and making musical instruments is a major craft occupation all over India.

Leather shadow puppet, Kerala

Musical Instruments

Music is an important component of the performing arts like dance and drama, and of rituals. Each community has its own style of music and tradition of songs.

There are essentially two ways to make music: with the human voice and with an instrument.

The musical instruments are classified on the basis of the scientific principle used to create the sound they make. They are briefly described below.

Percussion Instruments: These instruments are struck to produce sound. Often these are used to produce the taal or beat and do not produce all the musical notes—manjeera or cymbals.

Wind Instruments: These need air to flow through them to produce sound—bansuri or flute.

String Instruments: These are instruments that use one or many tightly tied strings that when struck vibrate to create sound—the veena or ektara.

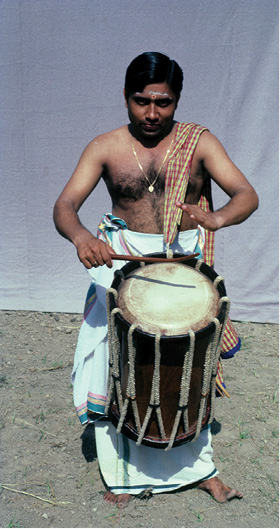

Drums: A drum is made of a membrane stretched across a hollow frame and played by striking — the dholak or mridangam.

Drums of India

A membrane made of hide, tautly stretched over a bowl or frame, is the key element in generating drum sounds — which is why this family of musical instruments is called membranophones. Tablas, dholaks, damrus, naggadas, chendas and many others fall in this category.

Drum makers are specialists; chiselling a solid block of wood to create just the right pitch is skilled work, and is very exacting. Although the drum base is sometimes carved, the craftsman is more concerned with the audio effect of the cavity, its size and shape, and the thickness of the wood that is to be used, than with the form or decoration of

the drum.

Dholak: We come across the dholakwallah most commonly in our cities. Though it looks simple, dholak making involves a great deal of effort. To start with, the wood has to be perfectly seasoned. Dholakwallahs buy the readymade wooden shells primarily from Amroha in Uttar Pradesh.

These shells are smoothened and vigorously polished with a special mud-paste. Thick string is toughened and interwoven through hooks in the shell. Goat leather flaps are hemmed onto the two sides—and the dholak is ready.

Then comes the sound testing routine—rhythmic tapping to determine if the notes are right.

Chenda player, Kerala

Dholakwallahs belong mainly to Uttar Pradesh coming from Barabanki, Gonda, Allahabad and Kanpur. They are nomadic and travel the length and breadth of the country selling their ‘wonder drums’ wherever they go. A market for dholaks exists all over India, with Delhi, Bombay, Lucknow and Amritsar as the main centres.

Dholaks are used by almost all sections of society during religious festivities and on special occasions like the birth of a child and weddings. The beat of a dholak can be regularly heard in temples and gurudwaras.

Damru: It is a tiny two-sided drum that often has a string and a stone fixed to it, and is used by the madari.

Try and find out which Hindu god is depicted playing a damru.

Naggadda: It is a large, resounding drum used in North India as accompaniment by folk performers in nautanki, or traditionally, to announce the arrival of royalty. It is played using drumsticks.

Naggadda player

Its South Indian counterpart is the chhenda that produces the sharp percussion that accompanies the Kathakali dance.

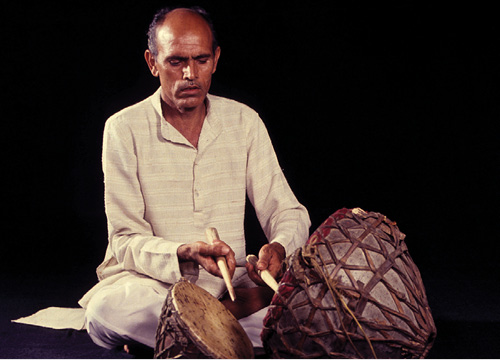

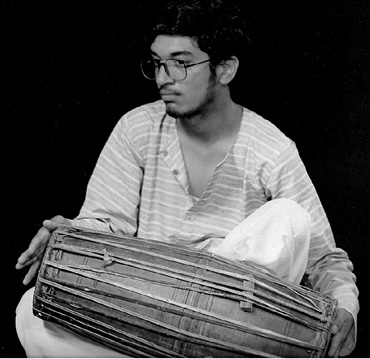

Pakhawaj player

Wind Instruments

In folk music a variety of wind instruments are popular, for example, flutes played both horizontally and vertically, algoja, pawa, satara, turhi, shehnai, shankh, been (pungi) etc.

Been: The snake-charmer’s been, a reed wind instrument of a strange shape is another commonplace sight in our cities. A been is made out of a kaddu (gourd), that has been dried and hollowed out. The saperas (snake charmers) plant the gourd creeper themselves, in a special way, so that the gourd does not touch the ground. Growing on the creeper, it develops a fully elongated shape, best suited for making the been.

Been player

The sapera selects a particular gourd and dries it in the shade as the rays of the sun can produce cracks on the outer skin. The gourd is then cleaned, seasoned and holes are made on the top and bottom of the instrument.

The panja or the reed portion is made separately. Two bamboo sticks, about a foot long are attached to the gourd with bees wax. One of the panjas provides a constant steady note: a drone, while the other is fashioned like a flute, with all the seven swaras or notes tuned, before it is attached. A fine tongue of kluck reed (kaanna) is inserted in both the panjas so that the tonal quality remains the same. The instrument is then blown upon to produce different melodies.

The been is accompanied by percussion instruments like the bugdoo, duff or dholki. A complete been orchestra consists of two beens, a bugdoo, a dholak and a duff.

Cowrie shells have always been associated with the been. Strings of these shells are tied around the rounded gourd and some of the shells may even be hung as tassels from one end of the been. Silken tassels and sometimes silver ornaments may be suspended from one end.

The sapera takes great pride in his been. It is usually hung from a cloth belt around his waist and when not in use, it hangs from a hook on a wall of his house. Tremendous stamina is required in order to play the been for long periods as it requires a lot of breath control.

Percussion Instruments

Chikka: It is an instrument unique to Punjab. Similar to the cane snake available in many parts of the country, the chikha is made up of 14 wooden sticks joint together as a lattice. By opening and sharply shutting the chikkha, a sharp sound similar to clapping is produced.

Chimta: Very similar to an actual pair of tongs used in the kitchen, the chimta has small metal discs loosely attached to it which strike against each other when the arms of the chimta are struck.

Mashak: It is made of the leather bag used by villagers to transport water! It is like a basic bagpipe, the national musical instrument of Scotland! The mashak is usually played by the Dholis of Rajasthan as accompaniment to popular folk melodies.

Kirla: It is a stick with a carved squirrel or fish at the top. A cord fixed to the top jerks the galad up with a sharp click, while bells fixed to the bottom of the kirla jingle.

Khadtaal: We often see this instrument depicted in the hands of Meerabai and other Bhaktikaleen poets of the Medieval period. Held in one hand, the khadtaal is made of two similar pieces of wood with brass fittings. One piece of it has space for a thumb, the other for four fingers, these are struck together to produce a simple percussive beat. It is easy to see the close resemblance between a khadtaal and the Spanish castanets, used as accompaniment for the famous Flamenco music and dance.

Manjeeras: These form an important part of the terah-tali dance, where they are worn all over the body! Manjeeras are a pair of flat metallic disks that are beaten together to produce a rhythmic metallic sound. Apart from a pair of manjeeras held in each hand, the terah-tali dancers wear manjeeras on their legs and additional ones on their arms and shoulders! Seated on the ground they rotate and sway—each movement being punctuated by the rhythmic sound of several manjeeras coming in contact with one another.

A pair of manjeeras

String Instruments

Instruments in which sound is produced by striking the strings made of iron, steel, brass or other metals as well as goat’s gut, cotton, silk threads etc. are known as string or chordophonic instruments. Some of the string instruments such as ektara, ravanhattha and gopijantra are used as accompanying instruments in traditional performances. Bhopas use the ektara while performing Bapuji ka phad, a tradtional story-telling performance of Rajasthan.

1. Here is a list of some of the drums of India: pakhawaj, mridangam, ghatam, thavil, dhol, maddalam, edakka, talam, nal, thumbak nari. Can you find out where each one is from? Investigate to find out how it is used, who makes it, its history, what other instruments are used along with it, and the names of these local instruments.

2. A wide range of craft objects are made especially for use in drama, dance or music performances such as masks, make-up, head-dresses, costumes, lightweight jewellery, sceneries and musical instruments. Study one such craft used in the performing arts tradition of your region. How is it made, who makes it, how is it used and what effect dose it create during the performance.

3. Make a map of different theatre forms in India.

4. Write a profile of an actor/performer from your region.

5. Several traditional theatre performances during harvest and Dussehra draw performers from specific occupational groups. Investigate this in your own region.

6. Theatre is a composite art form involving many different crafts and skills. Make a topic web to illustrate the idea.

7. Now that you have a bird’s eye view of Indian crafts, imagine yourself to be Chairman of the All India Handicrafts and Handloom Board. Devise a ten-point programme indicating your priorities for the development of the crafts sector. Give reasons for your answers.

Suggested Reading

Art and Rituals of the Warli Tribes of Maharashtra by Yashodhara Dalmia. Lalit Kala Academy, New Delhi.

Art and Swadeshi by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. Munshiram Manoharlal Publications Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi.

Arts and Crafts of India by Ilay Cooper and John Gillow. Thames and Hudson Ltd, London.

Children of Barren Women by Pupul Jayakar. Penguin Books.

Classical Musical Instruments by Suneera Kasliwal. Rupa & Co., Delhi.

Crafts and Craftsmen in Traditional India by M.K. Pal. Kanak Publications, Delhi.

Crafts of Himachal Pradesh by Subhashini Aryan and R. K. Datta Gupta. Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd, Ahmedabad.

Crafts of Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh by Jaya Jaitly. Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd, Ahmedabad.

Dynamic Folk Toys by Sudarshan Khanna. National Book Trust, New Delhi.

Folk Arts and Crafts of India by Jasleen Dhamija. Indus Publishing Co., Delhi.

Folk Theatre of India by Gargi Balwant. National Book Trust, New Delhi.

Forms and Many Forms of Mother Clay by Haku Shah. National Handlooms and Handicrafts Museum, New Delhi.

Gangadevi Tradition and Expression in Mithila Painting by Jyotindra Jain. Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd, Ahmedabad.

Hand Woven Fabrics of India by Dhamija, Jasleen and Jyotindra Jain. Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd, Ahmedabad.

Handicrafted Indian Enamel Jewellery by Riva Devi Sharma and

M. Varadarajan. Roli Books, Delhi.

Handicrafts of India by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya. Delhi.

Himachal Pradesh by H.K. Mattoo. National Book Trust, New Delhi.

Incredible India: Crafting Nature by Jaya Jaitly. Wisdom Tree, Delhi.

Indian Embroideries (Vol. II) by John Irvin and Margaret Hall,

S. R. Bastikar. Calico Museum of Textiles, Ahmedabad.

Indian Folk Arts and Crafts by Jasleen Dhamija. National Book Trust, New Delhi.

Indian Jewellery Ornaments and Decorative Art by Jamila Brijbhusan. Bombay.

Indian Textiles by S.K. Saraswati. The Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.

Indian Textiles by G.K. Ghosh and Shukla Ghosh. APH Publishing Corporation, New Delhi.

Indian Tye – Dyed Fabrics by Alfred Bihler, Eberhard Fischer and Marie Louise Nabholz. Calico Museum of Textiles, Ahmedabad.

Musical Instruments of India by S. Bandopadhyay. Orientalia, Varanasi and Delhi.

Painted Myths of Creation: Art and Ritual of an Indian Tribe by Jyotindra Jain. Lalit Kala Academy, New Delhi.

Paramparik Karigar. Rupa & Co., New Delhi.

Performance Traditions in India by Suresh Awasthi. National Book Trust, New Delhi.

Sari: The Kalakshetra Tradition by Shakuntala Ramani. Craft Education and Research Centre, Kalakshetra Foundation, Chennai.

Stone Craft of India (2 Volumes) by Neelam Chhibbar. Craft Council of India.

The Arts and Crafts of India and Ceylon by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. Today & Tomorrow’s Printers & Publishers, New Delhi.

The Arts of India by G.C.M. Birdwood. Rupa & Co., New Delhi.

The Earthen Drum by Pupul Jayakar. Penguin Books.

The Indian Craftsman by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi.

The Industrial Arts of India by G.C.M. Birdwood. Chapman & Hall, London.

Threads of Identity: Embroidery and Adornments of the Nomadic Rabaris by Judy Frater. Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd, Ahmedabad.

Traditional Wisdom – Bamboo and Cane Crafts of North-east India by M.P. Ranjan, Nilam Iyer and Ghanshyam Pandya, National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad.

Tye – Dyed Textiles of India: Tradition and Trade by Veronica Murphy and Rosemary Crill. Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd, Ahmedabad.

Visvakarma’s Children: Stories of India’s Craft People by Jaya Jaitly. Institute of Social Sciences and Concept Publishing Company, New Delhi.