Table of Contents

I

Early Societies

From the Beginning of Time

Writing and City Life

early societies

In this section, we will read about two themes relating to early societies. The first is about the beginnings of human existence, from the remote past, millions of years ago. You will learn how humans first emerged in Africa and how archaeologists have studied these early phases of history from remains of bones and stone tools.

Archaeologists have made attempts to reconstruct the lives of early people – to find out about the shelters in which they lived, the food they ate by gathering plant produce and hunting animals, and the ways in which they expressed themselves. Other important developments include the use of fire and of language. And, finally, you will see whether the lives of people who live by hunting and gathering today can help us to understand the past.

The second theme deals with some of the earliest cities – those of Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq. These cities developed around temples, and were centres of long-distance trade. Archaeological evidence – remains of old settlements – and an abundance of written material are used to reconstruct the lives of the different people who lived there – craftspeople, scribes, labourers, priests, kings and queens. You will notice how pastoral people played an important role in some of these towns. A question to think about is whether the many activities that went on in cities would have been possible if writing had not developed.

You may wonder as to how people who for millions of years had lived in forests, in caves or temporary shelters and rock shelters began to eventually live in villages and cities. Well, the story is a long one and is related to several developments that took place at least 5,000 years before the establishment of the first cities.

One of the most far-reaching changes was the gradual shift from nomadic life to settled agriculture, which began around 10,000 years ago. As you will see in Theme 1, prior to the adoption of agriculture, people had gathered plant produce as a source of food. Slowly, they learnt more about different kinds of plants – where they grew, the seasons when they bore fruit and so on. From this, they learnt to grow plants. In West Asia, wheat and barley, peas and various kinds of pulses were grown. In East and Southeast Asia, the crops that grew easily were millet and rice. Millet was also grown in Africa. Around the same time, people learnt how to domesticate animals such as sheep, goat, cattle, pig and donkey. Plant fibres such as cotton and flax, and animal fibres such as wool were now woven into cloth. Somewhat later, about 5,000 years ago, domesticated animals such as cattle and donkeys were harnessed to ploughs and carts.

These developments led to other changes as well. When people grew crops, they had to stay in the same place till the crops ripened. So, settled life became more common. And with that, people built more permanent structures in which to live.

This was also the time when some communities learnt how to make earthen pots. These were used to store grain and other produce, and to prepare and cook a variety of foods made from the new grains that were cultivated. In fact, a great deal of attention was given to processing foods to make them tasty and digestible.

The way stone tools were made also changed. While earlier methods of making tools continued, some tools and equipment were now smoothened and polished by an elaborate process of grinding. New equipment included mortars and pestles for processing and grinding grain, as well as stone axes and hoes, which were used to clear land for cultivation, as well as for digging the earth to sow seeds.

In some areas, people learnt to tap the ores of metals such as copper and tin. Sometimes, copper ores were collected and used for their distinctive bluish-green colour. This prepared the way for the more extensive use of metal for jewellery and for tools subsequently.

There was also a growing familiarity with other kinds of produce from distant lands (and seas). This included wood, stones, including precious and semi-precious stones, metals and shell, and obsidian (hardened) volcanic lava. Clearly, people were going from place to place, carrying goods and ideas with them.

With increasing trade, the growth of villages and towns, and the movements of people, in place of the small communities of early people there now grew small states. While these changes took place slowly, over several thousand years, the pace quickened with the growth of the first cities. Also, the changes had far-reaching consequences. Some scholars have described this as a revolution, as the lives of people were probably transformed beyond recognition. Look out for continuities and changes as you explore these two contrasting themes in early history.

Remember too, that we have selected only some examples of early societies for detailed study. There were other kinds of early societies, including farming communities and pastoral peoples. And there were other peoples who were hunter-gatherers as well as city dwellers, apart from the examples selected.

How to Read Timelines

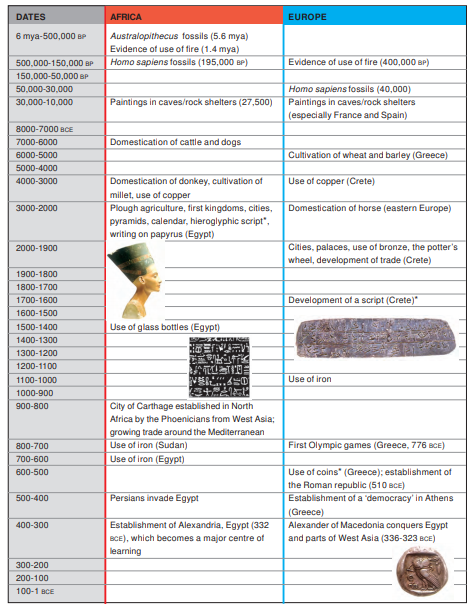

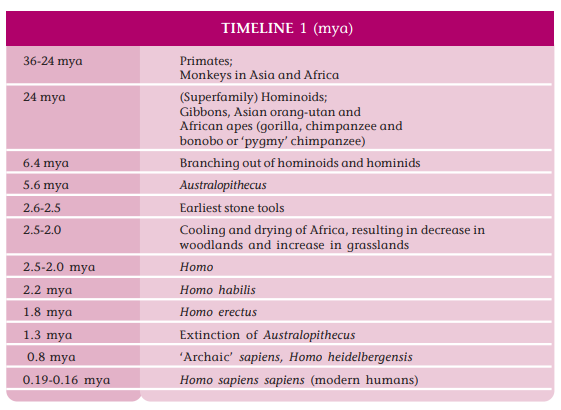

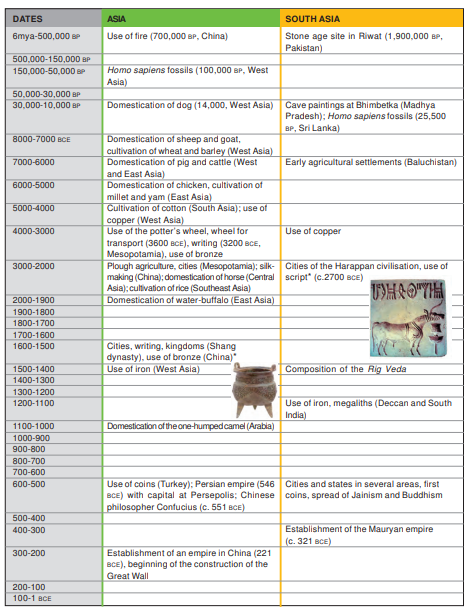

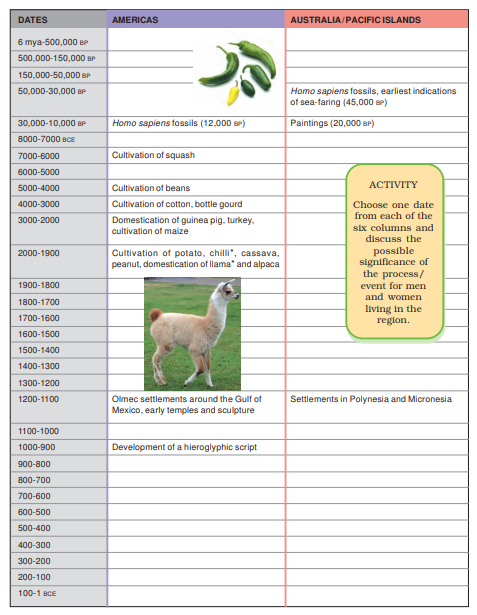

You will find a timeline like this one in every section.

Each of these will indicate some of the major processes and events in world history.

As you study the timelines, remember—

• Processes through which ordinary women and men have shaped history are far more difficult to date than events such as a war between kings.

• Some dates may indicate the beginning of a process, or when it reaches maturation.

• Historians are constantly revising dates in the light of new evidence, or new ways of assessing old data.

• While we have divided the timelines on a geographical basis as a matter of convenience, actual historical developments often transcend these divisions.

• Also, there is a chronological overlap in historical processes.

• Only some landmarks in human history have been shown here – we have highlighted the processes dealt with in the themes that follow, which also have separate timelines.

• Wherever you see a*, you will also find an illustration related to the date along the column.

• Blank spaces do not mean that nothing was happening – sometimes these indicate that we do not as yet know what was happening.

• You will be learning more about South Asian history in general and Indian history in particular next year. The dates selected for South Asia are only indicative of some

of the developments in the subcontinent.

Timeline i

(6 mya to 1 bce)

This timeline focuses on the emergence of humans and the domestication of plants and animals.

It highlights some major technological developments such as the use of fire, metals, plough agriculture and the wheel. Other processes that are shown include the emergence of cities and the use of writing. You will also find mention of some of the earliest empires – a theme that will be developed in Timeline II.

Theme 1

FROM THE BEGINNING OF TIME

This chapter traces the beginning of human existence. It was 5.6 million years ago (written as mya) that the first human-like creatures appeared on the earth’s surface. After this, several forms of humans emerged and then became extinct. Human beings resembling us (henceforth referred to as ‘modern humans’) originated about 160,000 years ago. During this long period of human history, people obtained food by either scavenging or hunting animals and gathering plant produce. They also learnt how to make stone tools and to communicate with each other.

Although other ways of obtaining food were adopted later, hunting-gathering continued. Even today there are hunter-gatherer societies in some parts of the world. This makes us wonder whether the lifestyles of present-day hunter-gatherers can tell us anything about the past.

Fossils are the remains or impressions of a very old plant, animal or human which have turned into stone. These are often embedded in rock, and are thus preserved for millions of years.

Species is a group of organisms that can breed to produce fertile offspring. Members of one species cannot mate with those of other species to produce fertile offspring.

Discoveries of human fossils, stone tools and cave paintings help us to understand early human history. Each of these discoveries has a history of its own. Very often, when such finds were first made, most scholars refused to accept that these fossils were the remains of early humans. They were also sceptical about the ability of early humans to make stone tools or paint. It was only over a period of time that the true significance of these finds was realised.

The evidence for human evolution comes from fossils of species of humans which have become extinct. Fossils can be dated either through direct chemical analysis or indirectly by dating the sediments in which they are buried. Once fossils are dated, a sequence of human evolution can be worked out.

When such discoveries were first made, about 200 years ago, many scholars were often reluctant to accept that fossils and other finds including stone tools and paintings were actually connected with early forms of humans. This reluctance generally stemmed from their belief in the Old Testament of the Bible, according to which human origin was regarded as an act of Creation by God.

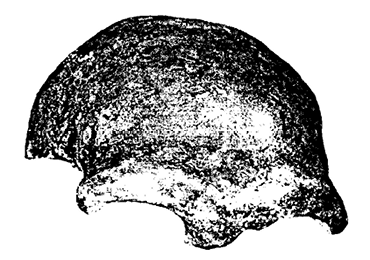

For instance, in August 1856, workmen who were quarrying for limestone in the Neander valley (see Map 2, p. 18), a gorge near the German city of Dusseldorf, found a skull and some skeletal fragments. These were handed over to Carl Fuhlrott, a local schoolmaster and natural historian, who realised that they did not belong to a modern human. He then made a plaster cast of the skull and sent it to Herman Schaaffhausen, a professor of anatomy at Bonn University. The following year they jointly published a paper, claiming that this skull represented a form of human that was extinct. At that time, scholars did not accept this view and instead declared that the skull belonged to a person of more recent times.

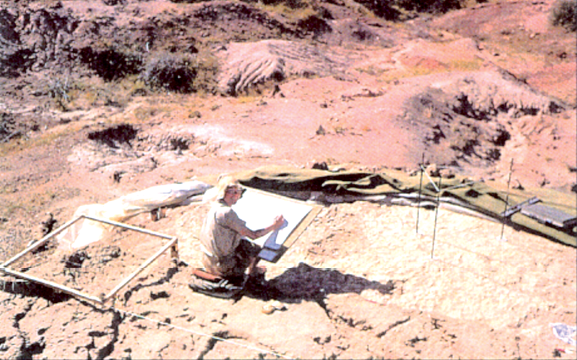

RECOVERING FOSSILS

A painstaking process. The precise location of finds is important for dating.

Shows the equipment used to record the location of finds. The square frame to the left of the archaeologist is a grid divided into 10 cm squares. Placing it over the find spot helps to record the horizontal position of the find. The triangular apparatus to the right is used to record the vertical position.

24 November 1859, when Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published, marked a landmark in the study of evolution. All 1,250 copies of the first print were sold out the same day. Darwin argued that humans had evolved from animals a long time ago.

The skull of Neanderthal man. Some of those who dismissed the antiquity of the skull regarded it as ‘brutish’ or that of a ‘pathological idiot’.

ACTIVITY 1

Most religions have stories about the creation of human beings which often do not correspond with scientific discoveries. Find out about some of these and compare them with the history of human evolution as discussed in this chapter.

ACTIVITY

Choose one date from each of the six columns and discuss the possible significance of the process/event for men and women living in the region.

The Story of Human Evolution

(a) The Precursors of Modern Human Beings

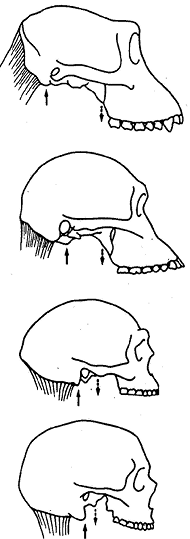

Look at these four skulls.

A belongs to an ape.

B belongs to a species known as Australopithecus (see below).

C belongs to a species known as Homo erectus (literally ‘upright man’).

D belongs to a species known as Homo sapiens (literally ‘thinking/wise man’} to which all present-day human beings belong.

List as many similarities and differences that you notice, looking carefully at the brain case, jaws and teeth.

Primates

are a subgroup of a larger group of mammals. They include monkeys, apes and humans. They have body hair, a relatively long gestation period following birth, mammary glands, different types of teeth, and the ability to maintain a constant body temperature.

The differences that you notice in the skulls shown in the illustration are some of the changes that came about as a result of human evolution. The story of human evolution is enormously long, and somewhat complicated. There are also many unanswered questions, and new data often lead to a revision and modification of earlier understandings. Let us look at some of the developments and their implications more closely.

It is possible to trace these developments back to between 36 and 24 mya. We sometimes find it difficult to conceptualise such long spans of time. If you consider a page of your book to represent 10,000 years, in itself a vast span of time, 10 pages would represent 100,000 years, and a 100 pages would equal 1 million years. To think of 36 million years, you would have to imagine a book 3,600 pages long! That was when primates, a category of mammals, emerged in Asia and Africa. Subsequently, by about 24 mya, there emerged a subgroup amongst primates, called hominoids. This included apes. And, much later, about 5.6 mya, we find evidence of the first hominids.

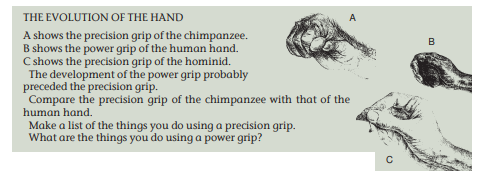

While hominids have evolved from hominoids and share certain common features, there are major differences as well. Hominoids have a smaller brain than hominids. They are quadrupeds, walking on all fours, but with flexible forelimbs. Hominids, by contrast, have an upright posture and bipedal locomotion (walking on two feet). There are also marked differences in the hand, which enables the making and use of tools. We will examine the kinds of tools made and their significance more closely later.

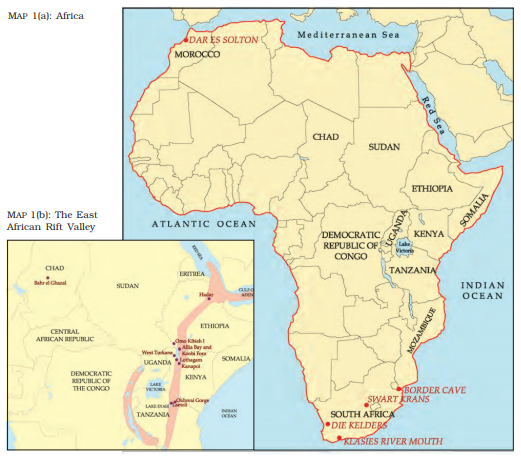

Two lines of evidence suggest an African origin for hominids. First, it is the group of African apes that are most closely related to hominids. Second, the earliest hominid fossils, which belong to the genus Australopithecus, have been found in East Africa and date back to about 5.6 mya. In contrast, fossils found outside Africa are no older than 1.8 million years.

Hominids belong to a family known as Hominidae, which includes all forms of human beings. The distinctive characteristics of hominids include a large brain size, upright posture, bipedal locomotion and specialisation of the hand.

Hominids are further subdivided into branches, known as genus, of which Australopithecus and Homo are important. Each of these in turn includes several species. The major differences between Australopithecus and Homo relate to brain size, jaws and teeth. The former has a smaller brain size, heavier jaws and larger teeth than the latter.

Virtually all the names given by scientists to species are derived from Latin and Greek words. For instance, the name Australopithecus comes from a Latin word, ‘austral’, meaning ‘southern’ and a Greek word, ‘pithekos’, meaning ‘ape.’ The name was given because this earliest form of humans still retained many features of an ape, such as a relatively small brain size in comparison to Homo, large back teeth and limited dexterity of the hands. Upright walking was also restricted, as they still spent a lot of time on trees. They retained characteristics (such as long forelimbs, curved hand and foot bones and mobile ankle joints) suited to life on trees. Over time, as tool making and long-distance walking increased, many human characteristics also developed.Hominoids are different from monkeys in a number of ways. They have a larger body and do not have a tail. Besides, there is a longer period of infant development and dependency amongst hominoids.

This is a view of the Olduvai Gorge in the Rift Valley, East Africa (see Map 1b, p.14), one of the areas from which traces of early human history have been recovered. Notice the different levels of earth at the centre of the photograph. Each of these represents a distinct geological phase.

The Discovery of Australopithecus, Olduvai Gorge, 17 July 1959

The Olduvai Gorge (see p. 14) was first ‘discovered’ in the early twentieth century by a German butterfly collector. However, Olduvai has come to be identified with Mary and Louis Leakey, who worked here for over 40 years. It was Mary Leakey who directed archaeological excavations at Olduvai and Laetoli and she made some of the most exciting discoveries. This is what Louis Leakey wrote about one of their most remarkable finds:

‘That morning I woke with a headache and a slight fever. Reluctantly, I agreed to spend the day in camp.With one of us out of commission, it was even more vital for the other to continue the work, for our precarious seven-week season was running out. So Mary departed for the diggings with Sally and Toots [two of their dogs] in the Land-Rover [a jeep-like vehicle], and I settled back to a restless day off.

Some time later – perhaps I dozed off – I heard the Land-Rover coming up fast to camp. I had a momentary vision of Mary stung by one of our hundreds of resident scorpions or bitten by a snake that had slipped past the dogs.

The Land-Rover rattled to a stop, and I heard Mary’s voice calling over and over: “I’ve got him! I’ve got him! I’ve got him!” Still groggy from the headache, I couldn’t make her out. “Got what? Are you hurt?” I asked. “Him, the man! Our man,” Mary said. “The one we’ve been looking for 23 years. Come quick, I’ve found his teeth!” ’

– From ‘Finding the World’s Earliest Man’, by L.S.B. Leakey, National Geographic, 118 (September 1960).

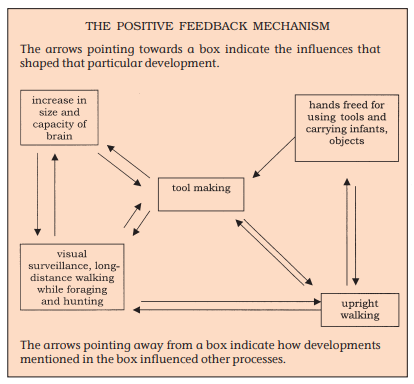

The remains of early humans have been classified into different species. These are often distinguished from one another on the basis of differences in bone structure. For instance, species of early humans are differentiated in terms of their skull size and distinctive jaws (see illustration on p.10). These characteristics may have evolved due to what has been called the positive feedback mechanism.

For example, bipedalism enabled hands to be freed for carrying infants or objects. In turn, as hands were used more and more, upright walking gradually became more efficient. Apart from the advantage of freeing hands for various uses, far less energy is consumed while walking as compared to the movement of a quadruped. However, the advantage in terms of saving energy is reversed while running. There is indirect evidence of bipedalism as early as 3.6 mya. This comes from the fossilised hominid footprints at Laetoli, Tanzania (see Section cover). Fossil limb bones recovered from Hadar, Ethiopia provide more direct evidence of bipedalism.

Around 2.5 mya, with the onset of a phase of glaciation (or an Ice Age), when large parts of the earth were covered with snow, there were major changes in climate and vegetation. Due to the reduction in temperatures as well as rainfall, grassland areas expanded at the expense of forests, leading to the gradual extinction of the early forms of Australopithecus (that were adapted to forests) and the replacement by species that were better adapted to the drier conditions. Among these were the earliest representatives of the genus Homo.

Homo is a Latin word, meaning ‘man’, although there were women as well! Scientists distinguish amongst several types of Homo. The names assigned to these species are derived from what are regarded as their typical characteristics. So fossils are classified as Homo habilis (the tool maker), Homo erectus (the upright man), and Homo sapiens (the wise or thinking man).

Fossils of Homo habilis have been discovered at Omo in Ethiopia and at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. The earliest fossils of Homo erectus have been found both in Africa and Asia: Koobi Fora and west Turkana, Kenya, Modjokerto and Sangiran, Java. As the finds in Asia belong to a later date than those in Africa, it is likely that hominids migrated from East Africa to southern and northern Africa, to southern and north-eastern Asia, and perhaps to Europe, some time between 2 and 1.5 mya. This species survived for nearly a million years.

In some instances, the names for fossils are derived from the places where the first fossils of a particular type were found. So fossils found in Heidelberg, a city in Germany, were called Homo heidelbergensis, while those found in the Neander valley (see p. 18) were categorised as Homo neanderthalensis.

The earliest fossils from Europe are of Homo heidelbergensis and Homo neanderthalensis. Both belong to the species of archaic (that is, old) Homo sapiens. The fossils of Homo heidelbergensis (0.8-0.1 mya) have a wide distribution, having been found in Africa, Asia and Europe. The Neanderthals occupied Europe and western and Central Asia from roughly 130,000 to 35,000 years ago. They disappeared abruptly in western Europe around 35,000 years ago.

In general, compared with Australopithecus, Homo have a larger brain, jaws with a reduced outward protrusion and smaller teeth (see illustration on p. 10). An increase in brain size is associated with more intelligence and a better memory. The changes in the jaws and teeth were probably related to differences in dietary habits.

The Story of Human Evolution

(b) Modern Human Beings

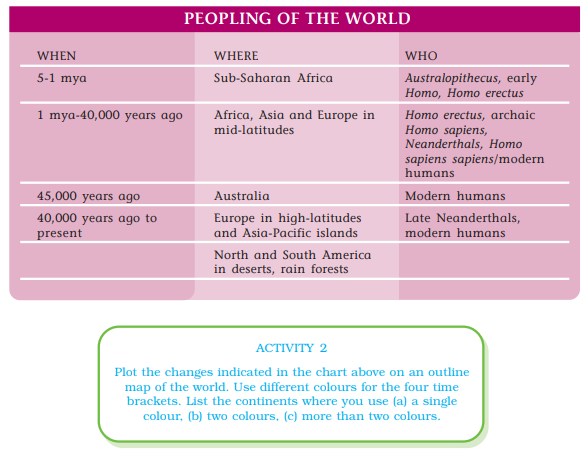

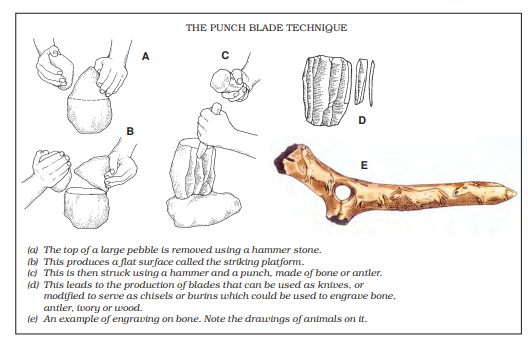

If you look at this chart, you will notice that some of the earliest evidence for Homo sapiens has been found in different parts of Africa. This raises the question of the centre of human origin. Was there a single centre or were there several?

The issue of the place of origin of modern humans has been much debated. Two totally divergent views have been expounded, one advocating the regional continuity model (with multiple regions of origin), the other the replacement model (with a single origin in Africa).

According to the regional continuity model, the archaic Homo sapiens in different regions gradually evolved at different rates into modern humans, and hence the variation in the first appearance of modern humans in different parts of the world. The argument is based on the regional differences in the features of present-day humans. According to those who advocate this view, these dissimilarities are due to differences between the pre-existing Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis populations that occupied the same regions.

The Replacement and Regional Continuity Models

The replacement model visualises the complete replacement everywhere of all older forms of humans with modern humans. In support of this view is the evidence of the genetic and anatomical homogeneity of modern humans. Those who suggest this argue that the enormous similarity amongst modern humans is due to their descent from a population that originated in a single region, which is Africa. The evidence of the earliest fossils of modern humans (from Omo in Ethiopia) also supports the replacement model. Scholars who hold this view suggest that the physical differences observed today among modern humans are the result of adaptation (over a span of thousands of years) by populations who migrated to the particular regions where they finally settled down.

Early Humans: Ways of Obtaining Food

So far, we have been considering the evidence of skeletal remains and seeing how these have been used to reconstruct the histories of the movements of peoples across continents. But, there are other, more routine aspects of human life as well. Let us see how these can be studied.

Early humans would have obtained food through a number of ways, such as gathering, hunting, scavenging and fishing. Gathering would involve collecting plant foods such as seeds, nuts, berries, fruits and tubers. That gathering was practised is generally assumed rather than conclusively established, as there is very little direct evidence for it. While we get a fair amount of fossil bones, fossilised plant remains are relatively rare. The only other way of getting information about plant intake would be if plant remains were accidentally burnt. This process results in carbonisation. In this form, organic matter is preserved for a long span of time. However, so far archaeologists have not found much evidence of carbonised seeds for this very early period.

In recent years, the term hunting has been under discussion by scholars. Increasingly, it is being suggested that the early hominids scavenged or foraged* for meat and marrow from the carcasses of animals that had died naturally or had been killed by other predators. It is equally possible that small mammals such as rodents, birds (and their eggs), reptiles and even insects (such as termites) were eaten by early hominids.

*Foraging means to search

for food.

Hunting probably began later – about 500,000 years ago. The earliest clear evidence for the deliberate, planned hunting and butchery of large mammals comes from two sites: Boxgrove in southern England (500,000 years ago) and Schoningen in Germany (400,000 years ago) (see Map 2 ). Fishing was also important, as is evident from the discovery of fish bones at different sites.

Map 2: Europe

From about 35,000 years ago, there is evidence of planned hunting from some European sites. Some sites, such as Dolni Vestonice (in the Czech Republic, see Map 2), which was near a river, seem to have been deliberately chosen by early people. Herds of migratory animals such as reindeer and horse probably crossed the river during their autumn and spring migrations and were killed on a large scale. The choice of such sites indicates that people knew about the movement of these animals and also about the means of killing large numbers of animals quickly.

Did men and women have different roles in gathering, scavenging, hunting and fishing? We do not really know. Today we find societies that live by hunting and gathering, where women and men undertake a range of different activities, but, as we will see later in the chapter, it is not always possible to suggest parallels with the past.

Early Humans

From Trees, to Caves and Open-air Sites

We are on surer ground when we try to reconstruct the evidence for patterns of residence. One way of doing this is by plotting the distribution of artefacts. For example, thousands of flake tools and hand axes have been excavated at Kilombe and Olorgesailie (Kenya). These finds are dated between 700,000 and 500,000 years ago.

Left: The site of Olorgesailie. The excavators, Mary and Louis Leakey, had a catwalk built around the site for observers.

Above: A close-up of tools found at the site, including hand axes.

How did these tools accumulate in one place? It is possible that some places, where food resources were abundant, were visited repeatedly. In such areas, people would tend to leave behind traces of their activities and presence, including artefacts. The deposited artefacts would appear as patches on the landscape. The places that were less frequently visited would have fewer artefacts, which may have been scattered over the surface.

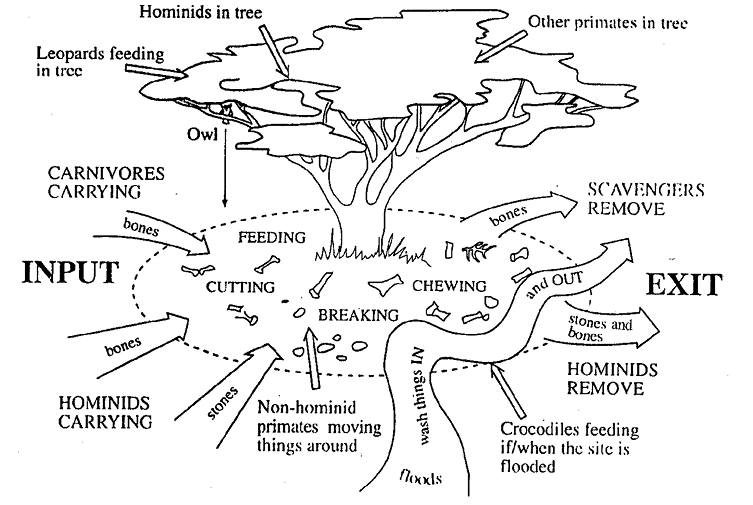

It is also important to remember that the same locations could have been shared by hominids, other primates and carnivores. Look at the diagram below to see how this may have worked.

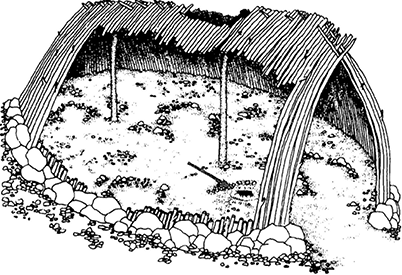

Between 400,000 and 125,000 years ago, caves and open-air sites began to be used. Evidence for this comes from sites in Europe. In the Lazaret cave in southern France, a 12x4 metre shelter was built against the cave wall. Inside it were two hearths and evidence of different food sources: fruits, vegetables, seeds, nuts, bird eggs and freshwater fish (trout, perch and carp). At another site, Terra Amata on the coast of southern France, flimsy shelters with roofs of wood and grasses were built for short-term, seasonal visits.

This is a reconstruction of a hut at Terra Amata. The large stone boulders were used to support the sides of the hut. The small scatters of stone on the floor were places where people made stone tools. The black spot marked with an arrow indicates a hearth.

In what ways do you think life for those who lived in this shelter would be different from that of the hominids who lived on trees?

Pieces of baked clay and burnt bone along with stone tools, dated between 1.4 and 1 mya, have been found at Chesowanja, Kenya and Swartkrans, South Africa. Were these the result of a natural bushfire or volcanic eruption? Or were they produced through the deliberate, controlled use of fire? We do not really know.

Hearths, on the other hand, are indications of the controlled use of fire. This had several advantages – fire provided warmth and light inside caves, and could be used for cooking. Besides, fire was used to harden wood, as for instance the tip of the spear. The use of heat also facilitated the flaking of tools. As important, fire could be used to scare away dangerous animals.

Early Humans: Making Tools

To start with, it is useful to remember that the use of tools and tool making are not confined to humans. Birds are known to make objects to assist them with feeding, hygiene and social encounters; and while foraging for food some chimpanzees use tools that they have made.

However, there are some features of human tool making that are not known among apes. As we have seen (see p. 11), certain anatomical and neurological (related to the nervous system) adaptations have led to the skilled use of hands, probably due to the important role of tools in human lives. Moreover, the ways in which humans use and make tools often require greater memory and complex organisational skills, both of which are absent in apes.

The earliest evidence for the making and use of stone tools comes from sites in Ethiopia and Kenya (see Map 1). It is likely that the earliest stone tool makers were the Australopithecus.

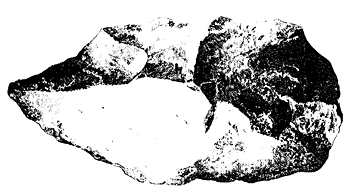

Some early tools.

These tools were found in Olduvai.

The one above is a chopper. This is a large stone from which flakes have been removed to produce a working edge.

The one below is a hand axe.

Can you suggest what these tools may have been used for?

As in the case of other activities, we do not know whether tool making was done by men or women or both. It is possible that stone tool makers were both women and men. Women in particular may have made and used tools to obtain food for themselves as well as to sustain their children after weaning.

About 35,000 years ago, improvements in the techniques for killing animals are evident from the appearance of new kinds of tools such as spear-throwers and the bow and arrow. The meat thus obtained was probably processed by removing the bones, followed by drying, smoking and storage. Thus, food could be stored for later consumption.

A spear-thrower. Note the carving on the handle. The use of the spear-thrower enabled hunters to hurl spears over longer distances.

Can you suggest any advantage in using such equipment?

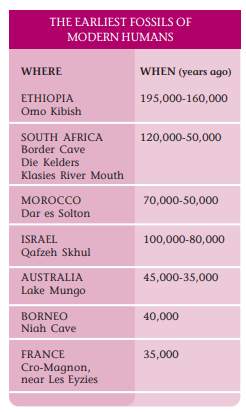

There were other changes, such as the trapping of fur-bearing animals (to use the fur for clothing) and the invention of sewing needles. The earliest evidence of sewn clothing comes from about 21,000 years ago. Besides, with the introduction of the punch blade technique to make small chisel-like tools, it was now possible to make engravings on bone, antler, ivory or wood.

Modes of Communication: Language and Art

Among living beings, it is humans alone that have a language. There are several views on language development: (1) that hominid language involved gestures or hand movements; (2) that spoken language was preceded by vocal but non-verbal communication such as singing or humming; (3) that human speech probably began with calls like the ones that have been observed among primates. Humans may have possessed a small number of speech sounds in the initial stage. Gradually, these may have developed into language.

When did spoken language emerge? It has been suggested that the brain of Homo habilis had certain features which would have made it possible for them to speak. Thus, language may have developed as early as 2 mya. The evolution of the vocal tract was equally important. This occurred around 200,000 years ago. It is more specifically associated with modern humans.

A third suggestion is that language developed around the same time as art, that is, around 40,000-35,000 years ago. The development of spoken language has been seen as closely connected with art, since both are media for communication.

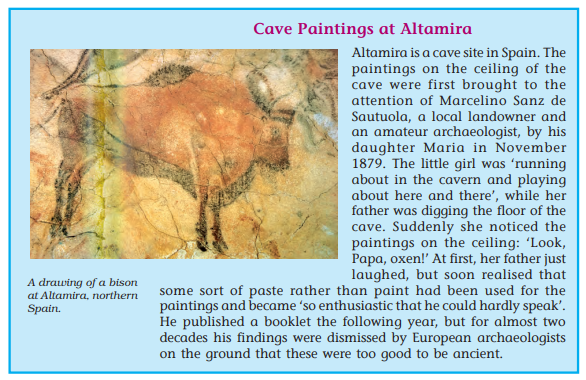

Hundreds of paintings of animals (done between 30,000 and12,000 years ago) have been discovered in the caves of Lascaux and Chauvet, both in France, and Altamira, in Spain. These include depictions of bison, horses, ibex, deer, mammoths, rhinos, lions, bears, panthers, hyenas and owls.

More questions have been raised than answered regarding these paintings. For example, why do some areas of caves have paintings and not others? Why were some animals painted and not others? Why were men painted both individually and in groups, whereas women were depicted only in groups? Why were men painted near animals but never women? Why were groups of animals painted in the sections of caves where sounds carried well?

Several explanations have been offered. One is that because of the importance of hunting, the paintings of animals were associated with ritual and magic. The act of painting could have been a ritual to ensure a successful hunt. Another explanation offered is that these caves were possibly meeting places for small groups of people or locations for group activities. These groups could share hunting techniques and knowledge, while paintings and engravings served as the media for passing information from one generation to the next.

The above account of early societies has been based on archaeological evidence. Clearly, there is much that we still do not know. As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, hunter-gatherer societies exist even today. Can one learn anything about past societies from present-day hunter-gatherers? This is a question we will address in the next section.

Early Encounters with Hunter-Gatherers in Africa

The following is an account by a member of an African pastoral group about its initial contact in 1870 with the !Kung San, a hunter-gatherer society living in the Kalahari desert:

When we first came into this area, all we saw were strange footprints in the sand. We wondered what kind of people these were. They were very afraid of us and would hide whenever we came around. We found their villages, but they were always empty because as soon as they saw strangers coming, they would scatter and hide in the bush. We said: ‘Oh, this is good; these people are afraid of us, they are weak and we can easily rule over them.’ So we just ruled them. There was no killing or fighting.

You will read more about encounters with hunter-gatherers in Themes 8 and 10.

The Hadza

‘The Hadza are a small group of hunters and gatherers, living in the vicinity of Lake Eyasi, a salt, rift-valley lake...The country of the eastern Hadza, dry, rocky savanna, dominated by thorn scrub and acacia trees...is rich in wild foods. Animals are exceptionally numerous and were certainly commoner at the beginning of the century. Elephant, rhinoceros, buffalo, giraffe, zebra, waterbuck, gazelle, warthog, baboon, lion, leopard, and hyena are all common, as are smaller animals such as porcupine, hare, jackal, tortoise and many others. All of these animals, apart from the elephant, are hunted and eaten by the Hadza. The amount of meat that could be regularly eaten without endangering the future of the game is probably greater than anywhere else in the world where hunters and gatherers live or have lived in the recent past.

Vegetable food – roots, berries, the fruit of the baobab tree, etc. – though not often obvious to the casual observer, is always abundant even at the height of the dry season in a year of drought. The type of vegetable food available is different in the six-month wet season from the dry season but there is no period of shortage. The honey and grubs of seven species of wild bee are eaten; supplies of these vary from season to season and from year to year.

Sources of water are widely distributed over the country in the wet season but are very few in the dry season. The Hadza consider that about 5-6 kilometres is the maximum distance over which water can reasonably be carried and camps are normally sited within a kilometre of a water course.

Part of the country consists of open grass plains but the Hadza never build camps there. Camps are invariably sited among trees or rocks and, by preference, among both.

The eastern Hadza assert no rights over land and its resources. Any individual may live wherever he likes and may hunt animals, collect roots, berries, and honey and draw water anywhere in Hadza country without any sort of restriction...

In spite of the exceptional numbers of game animals in their area, the Hadza rely mainly on wild vegetable matter for their food. Probably as much as 80 per cent of their food by weight is vegetable, while meat and honey together account for the remaining 20 per cent.

Camps are commonly small and widely dispersed in the wet season, large and concentrated near the few available sources of water in the dry season.

There is never any shortage of food even in the time of drought.’

– Written in 1960 by James Woodburn, an anthropologist.

Anthropology is a discipline that studies human culture and evolutionary aspects of human biology.

ACTIVITY 3

Why do the Hadza not assert rights over land and its resources? Why do the size and location of camps keep changing from season to season? Why is there never any shortage of food even in times of drought? Can you name any such hunter-gatherer societies in India today?

As our knowledge of present-day hunter-gatherers increased through studies by anthropologists, a question that began to be posed was whether the information about living hunters and gatherers could be used to understand past societies. Currently, there are two opposing views on this issue.

On one side are scholars who have directly applied specific data from present-day hunter-gatherer societies to interpret the archaeological remains of the past. For example, some archaeologists have suggested that the hominid sites, dated to 2 mya, along the margins of Lake Turkana could have been dry season camps of early humans, because such a practice has been observed among the Hadza and the !Kung San.

On the other side are scholars who feel that ethnographic data cannot be used for understanding past societies as the two are totally different. For instance, present-day hunter-gatherer societies pursue several other economic activities along with hunting and gathering. These include engaging in exchange and trade in minor forest produce, or working as paid labourers in the fields of neighbouring farmers. Moreover, these societies are totally marginalised in all senses – geographically, politically and socially. The conditions in which they live are very different from those of early humans.

Another problem is that there is tremendous variation amongst living hunter-gatherer societies. There are conflicting data on many issues such as the relative importance of hunting and gathering, group sizes, or the movement from place to place.

Also, there is little consensus regarding the division of labour in food procurement. Although today generally women gather and men hunt, there are societies where both women and men hunt and gather and make tools. In any case, the important role of women in contributing to the food supply in such societies cannot be denied. It is perhaps this factor that ensures a relatively equal role for both women and men in present-day hunter-gatherer societies, although there are variations. While this may be the case today, it is difficult to make any such inference for the past.

Epilogue

For several million years, humans lived by hunting wild animals and gathering wild plants. Then, between 10,000 and 4,500 years ago, people in different parts of the world learnt to domesticate certain plants and animals. This led to the development of farming and pastoralism as a way of life. The shift from foraging to farming was a major turning point in human history. Why did this change take place at this point of time?

The last ice age came to an end about 13,000 years ago and with that warmer, wetter conditions prevailed. As a result, conditions were favourable for the growth of grasses such as wild barley and wheat. At the same time, as open forests and grasslands expanded, the population of certain animal species such as wild sheep, goat, cattle, pig and donkey increased. What we find is that human societies began to gradually prefer areas that had an abundance of wild grasses and animals. Now relatively large, permanent communities occupied such areas for most parts of the year. With some areas being clearly preferred, a pressure may have built up to increase the food supply. This may have triggered the process of domestication of certain plants and animals. It is likely that a combination of factors which included climatic change, population pressure, a greater reliance on and knowledge of a few species of plants (such as wheat, barley, rice and millet) and animals (such as sheep, goat, cattle, donkey and pig) played a role in this transformation.

One such area where farming and pastoralism began around 10,000 years ago was the Fertile Crescent, extending from the Mediterranean coast to the Zagros mountains in Iran. With the introduction of agriculture, more people began to stay in one place for even longer periods than they had done before. Thus permanent houses began to be built of mud, mud bricks and even stone. These are some of the earliest villages known to archaeologists.

Farming and pastoralism led to the introduction of many other changes such as the making of pots in which to store grain and other produce, and to cook food. Besides, new kinds of stone tools came into use. Other new tools such as the plough were used in agriculture. Gradually, people became familiar with metals such as copper and tin. The wheel, important for both pot making and transportation, came into use.

About 5,000 years ago, even larger concentrations of people began to live together in cities. Why did this happen? And what are the differences between cities and other settlements? Look out for answers to these and other questions in Theme 2.

ACTIVITY 4

What do you think are the advantages and disadvantages of using ethnographic accounts to reconstruct the lives of the earliest peoples?

Exercises

Answer in brief

1. Look at the diagram showing the positive feedback mechanism on page 13. Can you list the inputs that went into tool making? What were the processes that were strengthened by tool making?

2. Humans and mammals such as monkeys and apes have certain similarities in behaviour and anatomy. This indicates that humans possibly evolved from apes. List these resemblances in two columns under the headings of (a) behaviour and (b) anatomy. Are there any differences that you think are noteworthy?

3. Discuss the arguments advanced in favour of the regional continuity model of human origins. Do you think it provides a convincing explanation of the archaeological evidence? Give reasons for your answer.

4. Which of the following do you think is best documented in the archaeological record: (a) gathering, (b) tool making, (c) the use of fire?

Answer in a short essay

5. Discuss the extent to which (a) hunting and (b) constructing shelters would have been facilitated by the use of language. What other modes of communication could have been used for these activities?

6. Choose any two developments each from Timelines 1 and 2 at the end of the chapter and indicate why you think these are significant.