Table of Contents

Theme 2

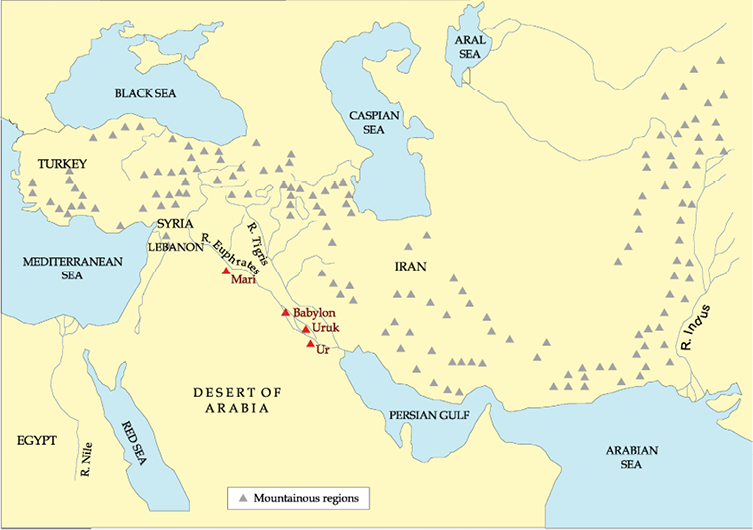

City life began in Mesopotamia*, the land between the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers that is now part of the Republic of Iraq. Mesopotamian civilisation is known for its prosperity, city life, its voluminous and rich literature and its mathematics and astronomy. Mesopotamia’s writing system and literature spread to the eastern Mediterranean, northern Syria, and Turkey after 2000 bce, so that the kingdoms of that entire region were writing to one another, and to the Pharaoh of Egypt, in the language and script of Mesopotamia. Here we shall explore the connection between city life and writing, and then look at some outcomes of a sustained tradition of writing.

*The name Mesopotamia is derived from the Greek wordsmesos, meaning middle, and potamos, meaning river.

In the beginning of recorded history, the land, mainly the urbanised south (see discussion below), was called Sumer and Akkad. After 2000 bce, when Babylon became an important city, the term Babylonia was used for the southern region. From about 1100 bce, when the Assyrians established their kingdom in the north, the region became known as Assyria. The first known language of the land was Sumerian. It was gradually replaced by Akkadian around 2400 bce when Akkadian speakers arrived. This language flourished till about Alexander’s time (336-323 bce), with some regional changes occurring. From 1400 bce, Aramaic also trickled in. This language, similar to Hebrew, became widely spoken after 1000 bce. It is still spoken in parts of Iraq.

Archaeology in Mesopotamia began in the 1840s. At one or two sites (including Uruk and Mari, which we discuss below), excavations continued for decades. (No Indian site has ever seen such long-term projects.) Not only can we study hundreds of Mesopotamian buildings, statues, ornaments, graves, tools and seals as sources, there are thousands of written documents.

Mesopotamia was important to Europeans because of references to it in the Old Testament, the first part of the Bible. For instance, the Book of Genesis of the Old Testament refers to ‘Shimar’, meaning Sumer, as a land of brick-built cities. Travellers and scholars of Europe looked on Mesopotamia as a kind of ancestral land, and when archaeological work began in the area, there was an attempt to prove the literal truth of the Old Testament.

From the mid-nineteenth century there was no stopping the enthusiasm for exploring the ancient past of Mesopotamia. In 1873, a British newspaper funded an expedition of the British Museum to search for a tablet narrating the story of the Flood, mentioned in the Bible.

By the 1960s, it was understood that the stories of the Old Testament were not literally true, but may have been ways of expressing memories about important changes in history. Gradually, archaeological techniques became far more sophisticated and refined. What is more, attention was directed to different questions, including reconstructing the lives of ordinary people. Establishing the literal truth of Biblical narratives receded into the background. Much of what we discuss subsequently in the chapter is based on these later studies.

According to the Bible, the Flood was meant to destroy all life on earth. However, God chose a man, Noah, to ensure that life could continue after the Flood. Noah built a huge boat, an ark. He took a pair each of all known species of animals and birds on board the ark, which survived the Flood. There was a strikingly similar story in the Mesopotamian tradition, where the principal character was called Ziusudra or Utnapishtim.

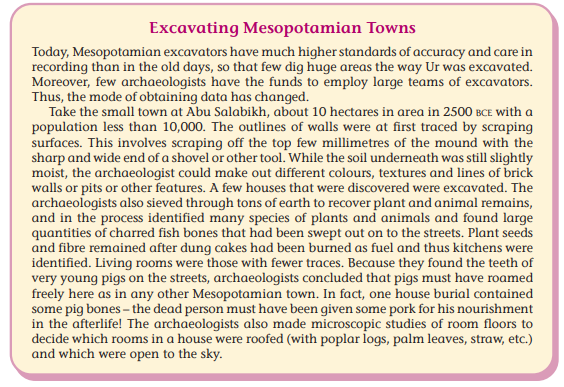

Map 1: West Asia

Activity 1

Many societies have myths about floods. These are often ways of preserving and expressing memories about important changes in history. Find out more about these, noting how life before and after the flood is represented.

Mesopotamia and its Geography

Iraq is a land of diverse environments. In the north-east lie green, undulating plains, gradually rising to tree-covered mountain ranges with clear streams and wild flowers, with enough rainfall to grow crops. Here, agriculture began between 7000 and 6000 bce. In the north, there is a stretch of upland called a steppe, where animal herding offers people a better livelihood than agriculture – after the winter rains, sheep and goats feed on the grasses and low shrubs that grow here. To the east, tributaries of the Tigris provide routes of communication into the mountains of Iran. The south is a desert – and this is where the first cities and writing emerged (see below). This desert could support cities because the rivers Euphrates and Tigris, which rise in the northern mountains, carry loads of silt (fine mud). When they flood or when their water is let out on to the fields, fertile silt is deposited.

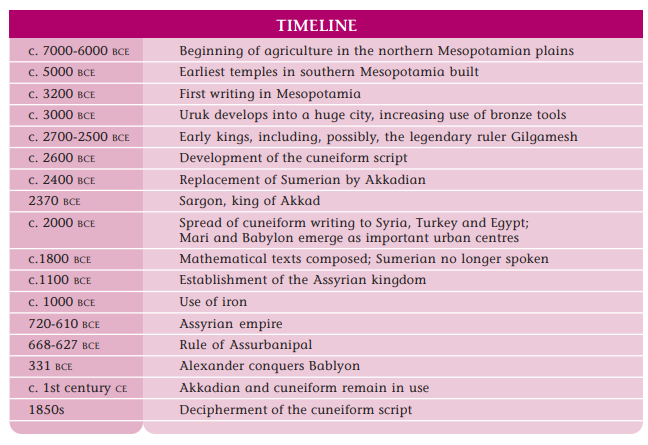

Map 2: Mesopotamia: Mountains, Steppe, Desert, Irrigated Zone of the South.

After the Euphrates has entered the desert, its water flows out into small channels. These channels flood their banks and, in the past, functioned as irrigation canals: water could be let into the fields of wheat, barley, peas or lentils when necessary. Of all ancient systems, that of the Roman Empire (Theme 3) included, it was the agriculture of southern Mesopotamia that was the most productive, even though the region did not have sufficient rainfall to grow crops.

Not only agriculture, Mesopotamian sheep and goats that grazed on the steppe, the north-eastern plains and the mountain slopes (that is, on tracts too high for the rivers to flood and fertilise) produced meat, milk and wool in abundance. Further, fish was available in rivers and date-palms gave fruit in summer. Let us not, however, make the mistake of thinking that cities grew simply because of rural prosperity. We shall discuss other factors by and by, but first let us be clear about city life.

The Significance of Urbanism

Cities and towns are not just places with large populations. It is when an economy develops in spheres other than food production that it becomes an advantage for people to cluster in towns. Urban economies comprise besides food production, trade, manufactures and services. City people, thus, cease to be self-sufficient and depend on the products or services of other (city or village) people. There is continuous interaction among them. For instance, the carver of a stone seal requires bronze tools that he himself cannot make, and coloured stones for the seals that he does not know where to get: his ‘specialisation’ is fine carving, not trading. The bronze tool maker does not himself go out to get the metals, copper and tin. Besides, he needs regular supplies of charcoal for fuel. The division of labour is a mark of urban life.

Further, there must be a social organisation in place. Fuel, metal, various stones, wood, etc., come from many different places for city manufacturers. Thus, organised trade and storage is needed. There are deliveries of grain and other food items from the village to the city, and food supplies need to be stored and distributed. Besides, many different activities have to be coordinated: there must be not only stones but also bronze tools and pots available for seal cutters. Obviously, in such a system some people give commands that others obey, and urban economies often require the keeping of written records.

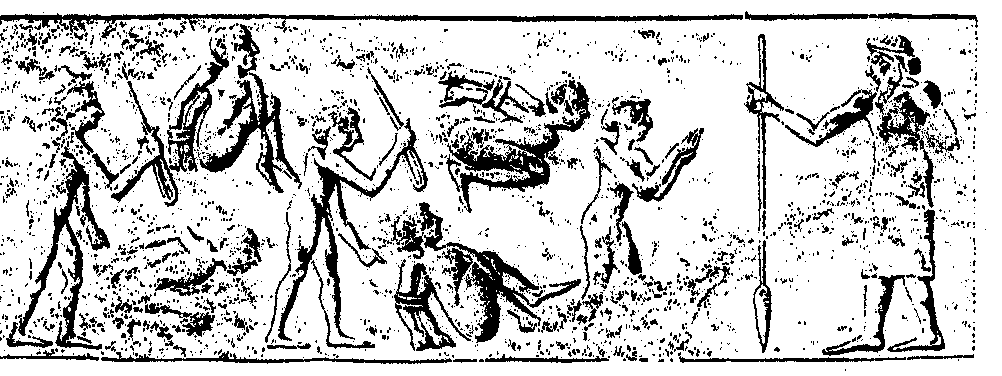

The earliest cities in Mesopotamia date back to the bronze age, c.3000 bce. Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin. Using bronze meant procuring these metals, often from great distances. Metal tools were necessary for accurate carpentry, drilling beads, carving stone seals, cutting shell for inlaid furniture, etc. Mesopotamian weapons were also of bronze – for example, the tips of the spears that you see in the illustration on p. 38.

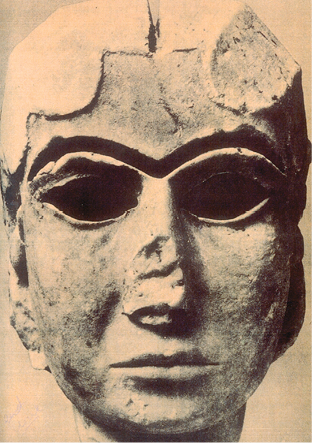

The Warka Head

This woman’s head was sculpted in white marble at Uruk before 3000 bce. The eyes and eyebrows would probably have taken lapis lazuli (blue) and shell (white) and bitumen (black) inlays, respectively. There is a groove along the top of the head, perhaps for an ornament. This is a world-famous piece of sculpture, admired for the delicate modelling of the woman’s mouth, chin and cheeks. And it was modelled in a hard stone that would have been imported from a distance.

Beginning with the procurement of stone, list all the specialists who would be involved in the production of such a piece of sculpture.

Activity 2

Discuss whether city life would have been possible without the use of metals.

Movement of Goods into Cities

However rich the food resources of Mesopotamia, its mineral resources were few. Most parts of the south lacked stones for tools, seals and jewels; the wood of the Iraqi date-palm and poplar was not good enough for carts, cart wheels or boats; and there was no metal for tools, vessels or ornaments. So we can surmise that the ancient Mesopotamians could have traded their abundant textiles and agricultural produce for wood, copper, tin, silver, gold, shell and various stones from Turkey and Iran, or across the Gulf. These latter regions had mineral resources, but much less scope for agriculture. Regular exchanges – possible only when there was a social organisation – to equip foreign expeditions and direct the exchanges were initiated by the people of southern Mesopotamia.

The Development of Writing

All societies have languages in which certain spoken sounds convey certain meanings. This is verbal communication. Writing too is verbal communication – but in a different way. When we talk about writing or a script, we mean that spoken sounds are represented invisible signs.

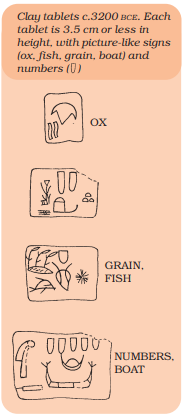

The first Mesopotamian tablets, written around 3200 bce, contained picture-like signs and numbers. These were about 5,000 lists of oxen, fish, bread loaves, etc. – lists of goods that were brought into or distributed from the temples of Uruk, a city in the south. Clearly, writing began when society needed to keep records of transactions – because in city life transactions occurred at different times, and involved many people and a variety of goods.

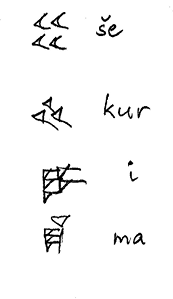

Cuneiform syllabic signs.

Cuneiform syllabic signs.

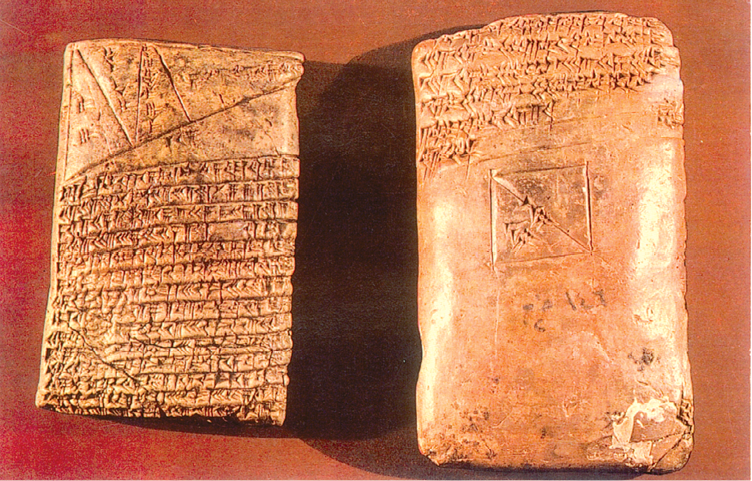

Mesopotamians wrote on tablets of clay. A scribe would wet clay and pat it into a size he could hold comfortably in one hand. He would carefully smoothen its surfaces. With the sharp end of a reed cut obliquely, he would press wedge-shaped (‘cuneiform*’) signs on to the smoothened surface while it was still moist. Once dried in the sun, the clay would harden and tablets would be almost as indestructible as pottery. When a written record of, say, the delivery of pieces of metal had ceased to be relevant, the tablet was thrown away. Once the surface dried, signs could not be pressed on to a tablet: so each transaction, however minor, required a separate written tablet. This is why tablets occur by the hundreds at Mesopotamian sites. And it is because of this wealth of sources that we know so much more about Mesopotamia than we do about contemporary India.

A clay tablet written on both sides in cuneiform. It is a mathematical exercise – you can see a triangle and lines across the triangle on the top of the obverse side. You can see that the letters have been pressed into the clay.

* Cuneiform is derived from the Latin words cuneus, meaning ‘wedge’ and forma, meaning ‘shape’.

By 2600 bce or so, the letters became cuneiform, and the language was Sumerian. Writing was now used not only for keeping records, but also for making dictionaries, giving legal validity to land transfers, narrating the deeds of kings, and announcing the changes a king had made in the customary laws of the land. Sumerian, the earliest known language of Mesopotamia, was gradually replaced after 2400 bce by the Akkadian language. Cuneiform writing in the Akkadian language continued in use until the first century ce, that is, for more than 2,000 years.

The System of Writing

The sound that a cuneiform sign represented was not a single consonant or vowel (such as m or a in the English alphabet), but syllables (say, -put-, or -la-, or -in-). Thus, the signs that a Mesopotamian scribe had to learn ran into hundreds, and he had to be able to handle a wet tablet and get it written before it dried. So, writing was a skilled craft but, more important, it was an enormous intellectual achievement, conveying in visual form the system of sounds of a particular language.

Literacy

Very few Mesopotamians could read and write. Not only were there hundreds of signs to learn, many of these were complex (see p. 33). If a king could read, he made sure that this was recorded in one of his boastful inscriptions! For the most part, however, writing reflected the mode of speaking.

A letter from an official would have to be read out to the king. So it would begin:

‘To my lord A, speak: … Thus says your servant B: … I have carried out the work assigned to me ...’

A long mythical poem about creation ends thus:

‘Let these verses be held in remembrance and let the elder teach them;

let the wise one and the scholar discuss them;

let the father repeat them to his sons;

let the ears of (even) the herdsman be opened to them.’

The Uses of Writing

The connection between city life, trade and writing is brought out in a long Sumerian epic poem about Enmerkar, one of the earliest rulers of Uruk. In Mesopotamian tradition, Uruk was the city par excellence, often known simply as The City.

Enmerkar is associated with the organisation of the first trade of Sumer: in the early days, the epic says, ‘trade was not known’. Enmerkar wanted lapis lazuli and precious metals for the beautification of a city temple and sent his messenger out to get them from the chief of a very distant land called Aratta. ‘The messenger heeded the word of the king. By night he went just by the stars. By day, he would go by heaven’s sun divine. He had to go up into the mountain ranges, and had to come down out of the mountain ranges. The people of Susa (a city) below the mountains saluted him like tiny mice*. Five mountain ranges, six mountain ranges, seven mountain ranges he crossed...’

*The poet means that once the messenger had climbed to a great height, everything appeared small in the valley far below.

The messenger could not get the chief of Aratta to part with lapis lazuli or silver, and he had to make the long journey back and forth, again and again, carrying threats and promises from the king of Uruk. Ultimately, the messenger ‘grew weary of mouth’. He got all the messages mixed up. Then, ‘Enmerkar formed a clay tablet in his hand, and he wrote the words down. In those days, there had been no writing down of words on clay.’

Given the written tablet, ‘the ruler of Aratta examined the clay. The spoken words were nails*. His face was frowning. He kept looking at the tablet.’

*Cuneiform letters were wedge shaped, hence, like nails.

This should not be taken as the literal truth, but it can be inferred that in Mesopotamian understanding it was kingship that organised trade and writing. This poem also tells us that, besides being a means of storing information and of sending messages afar, writing was seen as a sign of the superiority of Mesopotamian urban culture.

Urbanisation in Southern Mesopotamia:

Temples and Kings

From 5000 bce, settlements had begun to develop in southern Mesopotamia. The earliest cities emerged from some of these settlements. These were of various kinds: those that gradually developed around temples; those that developed as centres of trade; and imperial cities. It is cities of the first two kinds that will be discussed here.

Early settlers (their origins are unknown) began to build and rebuild temples at selected spots in their villages. The earliest known temple was a small shrine made of unbaked bricks. Temples were the residences of various gods: of the Moon God of Ur, or of Inanna the Goddess of Love and War. Constructed in brick, temples became larger over time, with several rooms around open courtyards. Some of the early ones were possibly not unlike the ordinary house – for the temple was the house of a god. But temples always had their outer walls going in and out at regular intervals, which no ordinary building ever had.

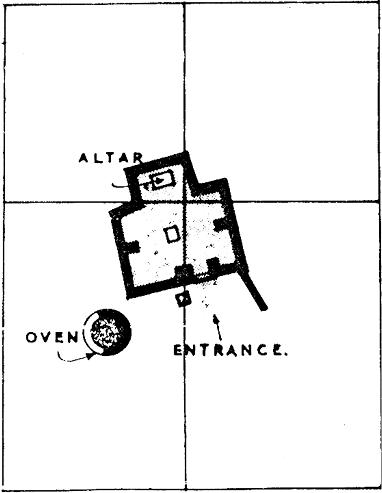

The earliest known temple of the south, c.5000 bce (plan).

The god was the focus of worship: to him or her people brought grain, curd and fish (the floors of some early temples had thick layers of fish bones). The god was also the theoretical owner of the agricultural fields, the fisheries, and the herds of the local community. In time, the processing of produce (for example, oil pressing, grain grinding, spinning, and the weaving of woollen cloth) was also done in the temple. Organiser of production at a level above the household, employer of merchants and keeper of written records of distributions and allotments of grain, plough animals, bread, beer, fish, etc., the temple gradually developed its activities and became the main urban institution. But there was also another factor on the scene.

In spite of natural fertility, agriculture was subject to hazards. The natural outlet channels of the Euphrates would have too much water one year and flood the crops, and sometimes they would change course altogether. As the archaeological record shows, villages were periodically relocated in Mesopotamian history. There were man-made problems as well. Those who lived on the upstream stretches of a channel could divert so much water into their fields that villages downstream were left without water. Or they could neglect to clean out the silt from their stretch of the channel, blocking the flow of water further down. So the early Mesopotamian countryside saw repeated conflict over land and water.

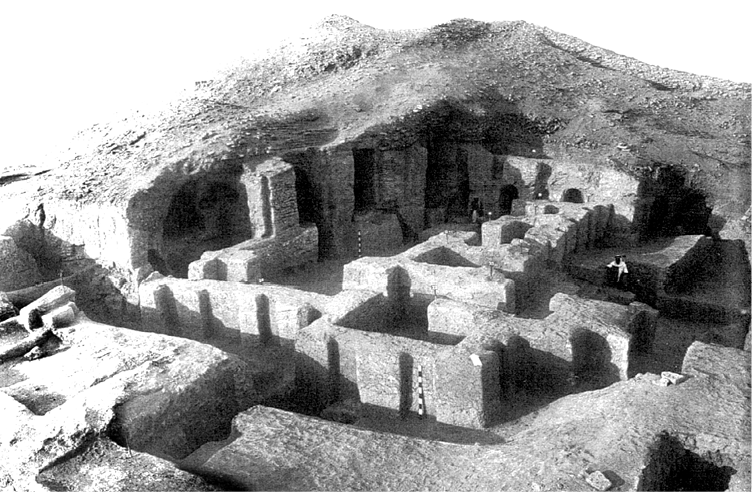

A temple of a later period, c.3000 bce, with an open courtyard and in-and-out façade (as excavated).

When there was continuous warfare in a region, those chiefs who had been successful in war could oblige their followers by distributing the loot, and could take prisoners from the defeated groups to employ as their guards or servants. So they could increase their influence and clout. Such war leaders, however, would be here today and gone tomorrow – until a time came when such leadership came to increase the well-being of the community with the creation of new institutions or practices. In time, victorious chiefs began to offer precious booty to the gods and thus beautify the community’s temples. They would send men out to fetch fine stones and metal for the benefit of the god and community and organise the distribution of temple wealth in an efficient way by accounting for things that came in and went out. As the poem about Enmerkar shows, this gave the king high status and the authority to command the community.

We can imagine a mutually reinforcing cycle of development in which leaders encouraged the settlement of villagers close to themselves, to be able to rapidly get an army together. Besides, people would be safe living in close proximity to one another. At Uruk, one of the earliest temple towns, we find depictions of armed heroes and their victims, and careful archaeological surveys have shown that around 3000 bce, when Uruk grew to the enormous extent of 250 hectares – twice as large as Mohenjo-daro would be in later centuries – dozens of small villages were deserted. There had been a major population shift. Significantly, Uruk also came to have a defensive wall at a very early date. The site was continuously occupied from about 4200 bce to about 400 ce, and by about 2800 bce it had expanded to 400 hectares.

War captives and local people were put to work for the temple, or directly for the ruler. This, rather than agricultural tax, was compulsory. Those who were put to work were paid rations. Hundreds of ration lists have been found, which give, against people’s names, the quantities of grain, cloth or oil allotted to them. It has been estimated that one of the temples took 1,500 men working 10 hours a day, five years to build.

Top: Basalt stele* showing a bearded man twice. Note his headband and hair, waistband and long skirt. In the lower scene he attacks a lion with a huge bow and arrow. In the scene above, the hero finally kills the rampant lion with a spear (c.3200 bce).

With rulers commanding people to fetch stones or metal ores, to come and make bricks or lay the bricks for a temple, or else to go to a distant country to fetch suitable materials, there were also technical advances at Uruk around 3000 bce. Bronze tools came into use for various crafts. Architects learnt to construct brick columns, there being no suitable wood to bear the weight of the roof of large halls.

Hundreds of people were put to work at making and baking clay cones that could be pushed into temple walls, painted in different colours, creating a colourful mosaic. In sculpture, there were superb achievements, not in easily available clay but in imported stone. And then there was a technological landmark that we can say is appropriate to an urban economy: the potter’s wheel. In the long run, the wheel enables a potter’s workshop to ‘mass produce’ dozens of similar pots at a time.

*Steles are stone slabs with inscriptions or carvings.

Impression of a cylinder seal, c.3200 bce. The bearded and armed standing figure is similar in dress and hairstyle to the hero in the stele* shown above.

Note three prisoners of war, their arms bound, and a fourth man beseeching the war leader.

The Seal – An Urban Artefact

Five early cylinder seals and their impressions. Describe what you see in each of the impressions. Is the cuneiform script shown on them?

In India, early stone seals were stamped. In Mesopotamia until the end of the first millennium bce, cylindrical stone seals, pierced down the centre, were fitted with a stick and rolled over wet clay so that a continuous picture was created. They were carved by very skilled craftsmen, and sometimes carry writing: the name of the owner, his god, his official position, etc. A seal could be rolled on clay covering the string knot of a cloth package or the mouth of a pot, keeping the contents safe. When rolled on a letter written on a clay tablet, it became a mark of authenticity. So the seal was the mark of a city dweller’s role in public life.

Life in the City

What we have seen is that a ruling elite had emerged: a small section of society had a major share of the wealth. Nothing makes this fact as clear as the enormous riches (jewellery, gold vessels, wooden musical instruments inlaid with white shell and lapis lazuli, ceremonial daggers of gold, etc.) buried with some kings and queens at Ur. But what of the ordinary people?

We know from the legal texts (disputes, inheritance matters, etc.) that in Mesopotamian society the nuclear family* was the norm, although a married son and his family often resided with his parents. The father was the head of the family. We know a little about the procedures for marriage. A declaration was made about the willingness to marry, the bride’s parents giving their consent to the marriage. Then a gift was given by the groom’s people to the bride’s people. When the wedding took place, gifts were exchanged by both parties, who ate together and made offerings in a temple. When her mother-in-law came to fetch her, the bride was given her share of the inheritance by her father. The father’s house, herds, fields, etc., were inherited by the sons.

*A nuclear family comprises a man, his wife and children.

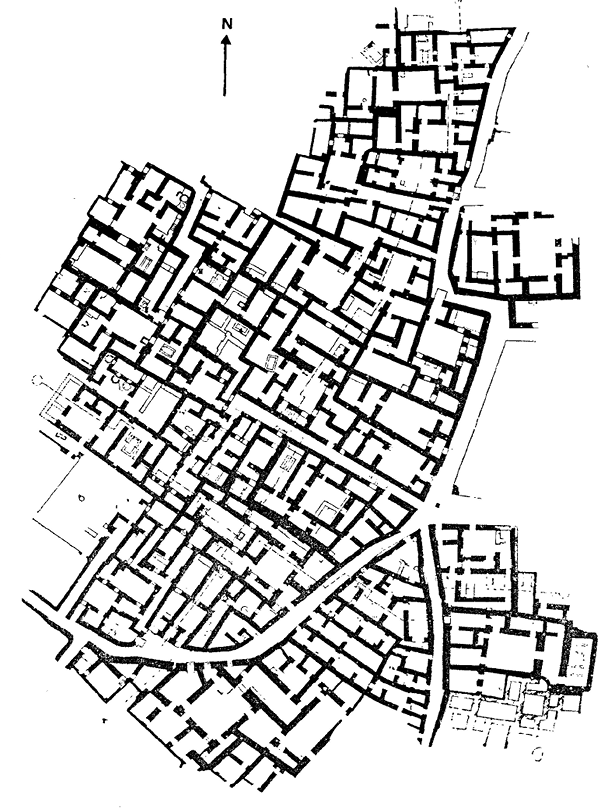

Let us look at Ur, one of the earliest cities to have been excavated. Ur was a town whose ordinary houses were systematically excavated in the 1930s. Narrow winding streets indicate that wheeled carts could not have reached many of the houses. Sacks of grain and firewood would have arrived on donkey-back. Narrow winding streets and the irregular shapes of house plots also indicate an absence of town planning. There were no street drains of the kind we find in contemporary Mohenjo-daro. Drains and clay pipes were instead found in the inner courtyards of the Ur houses and it is thought that house roofs sloped inwards and rainwater was channelled via the drainpipes into sumps* in the inner courtyards. This would have been a way of preventing the unpaved streets from becoming excessively slushy after a downpour.

*A sump is a covered basin in the ground into which water and sewage flow.

A residential area at Ur, c. 2000 bce. Can you locate, besides the winding streets, two or three blind alleys?

Yet people seem to have swept all their household refuse into the streets, to be trodden underfoot! This made street levels rise, and over time the thresholds of houses had also to be raised so that no mud would flow inside after the rains. Light came into the rooms not from windows but from doorways opening into the courtyards: this would also have given families their privacy. There were superstitions about houses, recorded in omen tablets at Ur: a raised threshold brought wealth; a front door that did not open towards another house was lucky; but if the main wooden door of a house opened outwards (instead of inwards), the wife would be a torment to her husband!

There was a town cemetery at Ur in which the graves of royalty and commoners have been found, but a few individuals were found buried under the floors of ordinary houses.

A Trading Town in a Pastoral Zone

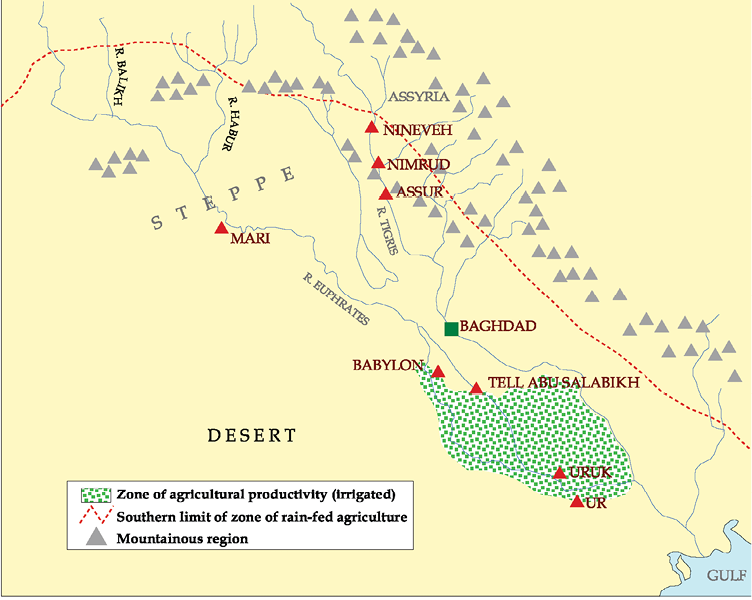

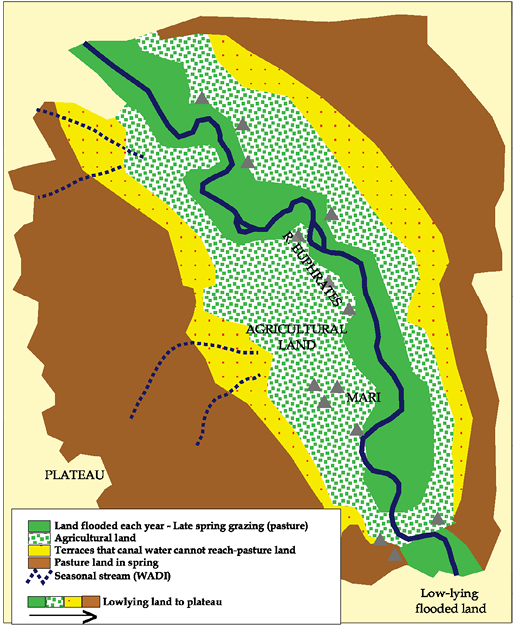

After 2000 bce the royal capital of Mari flourished. You will have noticed (see Map 2) that Mari stands not on the southern plain with its highly productive agriculture but much further upstream on the Euphrates. Map 3 with its colour coding shows that agriculture and animal rearing were carried out close to each other in this region. Some communities in the kingdom of Mari had both farmers and pastoralists, but most of its territory was used for pasturing sheep and goats.

Map 3: The Location of Mari

Herders need to exchange young animals, cheese, leather and meat in return for grain, metal tools, etc., and the manure of a penned flock is also of great use to a farmer. Yet, at the same time, there may be conflict. A shepherd may take his flock to water across a sown field, to the ruin of the crop. Herdsmen being mobile can raid agricultural villages and seize their stored goods. For their part, settled groups may deny pastoralists access to river and canal water along a certain set of paths.

Through Mesopotamian history, nomadic communities of the western desert filtered into the prosperous agricultural heartland. Shepherds would bring their flocks into the sown area in the summer. Such groups would come in as herders, harvest labourers or hired soldiers, occasionally become prosperous, and settle down. A few gained the power to establish their own rule. These included the Akkadians, Amorites, Assyrians and Aramaeans. (You will read more about rulers from pastoral societies in Theme 5.) The kings of Mari were Amorites whose dress differed from that of the original inhabitants and who respected not only the gods of Mesopotamia but also raised a temple at Mari for Dagan, god of the steppe. Mesopotamian society and culture were thus open to different people and cultures, and the vitality of the civilisation was perhaps due to this intermixture.

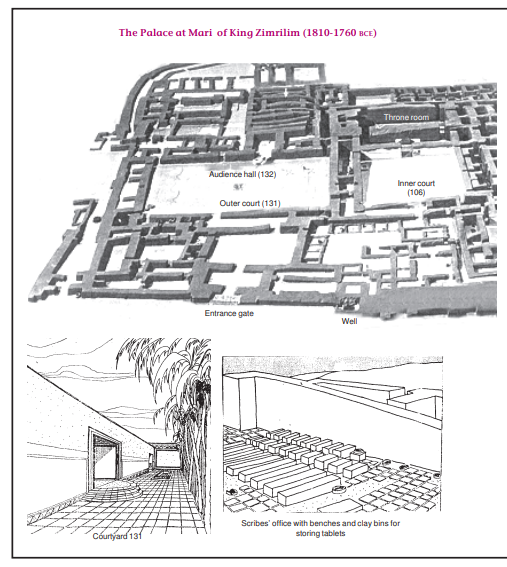

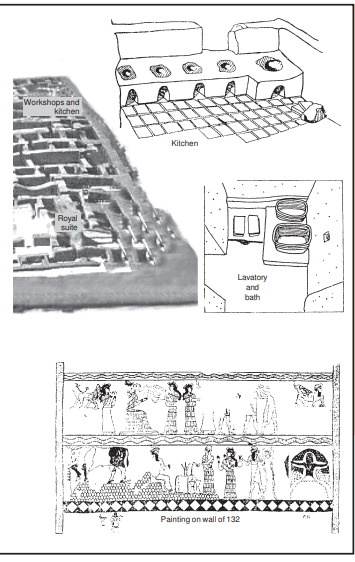

The Palace at Mari of King Zimrilim (1810-1760 bce)

The great palace of Mari was the residence of the royal family, the hub of administration, and a place of production, especially of precious metal ornaments. It was so famous in its time that a minor king came from north Syria just to see it, carrying with him a letter of introduction from a royal friend of the king of Mari, Zimrilim. Daily lists reveal that huge quantities of food were presented each day for the king’s table: flour, bread, meat, fish, fruit, beer and wine. He probably ate in the company of many others, in or around courtyard 106, paved white. You will notice from the plan that the palace had only one entrance, on the north. The large, open courtyards such as 131 were beautifully paved. The king would have received foreign dignitaries and his own people in 132, a room with wall paintings that would have awed the visitors. The palace was a sprawling structure, with 260 rooms and covered an area of 2.4 hectares.

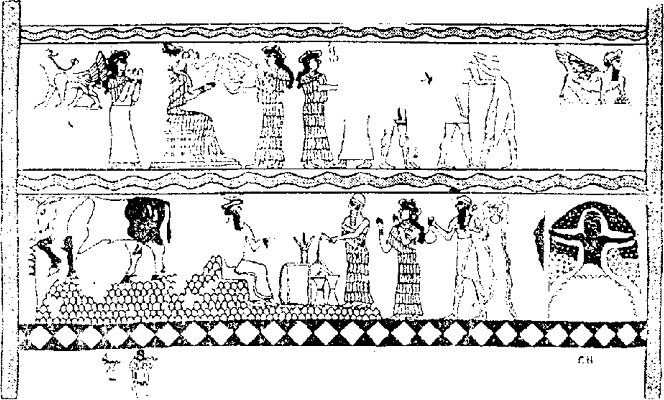

Painting on wall of 132

Activity 3

Trace the route from the entrance to the inner court.

What do you think would have been kept in the storerooms?

How has the kitchen been identified?

The kings of Mari, however, had to be vigilant; herders of various tribes were allowed to move in the kingdom, but they were watched. The camps of herders are mentioned frequently in letters between kings and officials. In one letter, an officer writes to the king that he has been seeing frequent fire signals at night – sent by one camp to another – and he suspects that a raid or an attack is being planned.

Located on the Euphrates in a prime position for trade – in wood, copper, tin, oil, wine, and various other goods that were carried in boats along the Euphrates – between the south and the mineral-rich uplands of Turkey, Syria and Lebanon, Mari is a good example of an urban centre prospering on trade. Boats carrying grinding stones, wood, and wine and oil jars, would stop at Mari on their way to the southern cities. Officers of this town would go aboard, inspect the cargo (a single river boat could hold 300 wine jars), and levy a charge of about one-tenth the value of the goods before allowing the boat to continue downstream. Barley came in special grain boats. Most important, tablets refer to copper from ‘Alashiya’, the island of Cyprus, known for its copper, and tin was also an item of trade. As bronze was the main industrial material for tools and weapons, this trade was of great importance. Thus, although the kingdom of Mari was not militarily strong, it was exceptionally prosperous.

Cities in Mesopotamian Culture

Mesopotamians valued city life in which people of many communities and cultures lived side by side. After cities were destroyed in war, they recalled them in poetry.

The most poignant reminder to us of the pride Mesopotamians took in their cities comes at the end of the Gilgamesh Epic, which was written on twelve tablets. Gilgamesh is said to have ruled the city of Uruk some time after Enmerkar. A great hero who subdued people far and wide, he got a shock when his heroic friend died. He then set out to find the secret of immortality, crossing the waters that surround the world. After a heroic attempt, Gilgamesh failed, and returned to Uruk. There, he consoled himself by walking along the city wall, back and forth. He admired the foundations made of fired bricks that he had put into place. It is on the city wall of Uruk that the long tale of heroism and endeavour fizzles out. Gilgamesh does not say that even though he will die his sons will outlive him, as a tribal hero would have done. He takes consolation in the city that his people had built.

The Legacy of Writing

While moving narratives can be transmitted orally, science requires written texts that generations of scholars can read and build upon. Perhaps the greatest legacy of Mesopotamia to the world is its scholarly tradition of time reckoning and mathematics.

Dating around 1800 bce are tablets with multiplication and division tables, square- and square-root tables, and tables of compound interest. The square root of 2 was given as:

If you work this out, you will find that the answer is 1.41421296, only slightly different from the correct answer, 1.41421356. Students had to solve problems such as the following: a field of area such and such is covered one finger deep in water; find out the volume of water.

The division of the year into 12 months according to the revolution of the moon around the earth, the division of the month into four weeks, the day into 24 hours, and the hour into 60 minutes – all that we take for granted in our daily lives – has come to us from the Mesopotamians. These time divisions were adopted by the successors of Alexander and from there transmitted to the Roman world, then to the world of Islam, and then to medieval Europe (see Theme 7 for how this happened).

Whenever solar and lunar eclipses were observed, their occurrence was noted according to year, month and day. So too there were records about the observed positions of stars and constellations in the night sky.

None of these momentous Mesopotamian achievements would have been possible without writing and the urban institution of schools, where students read and copied earlier written tablets, and where some boys were trained to become not record keepers for the administration, but intellectuals who could build on the work of their predecessors.

We would be mistaken if we think that the preoccupation with the urban world of Mesopotamia is a modern phenomenon. Let us look, finally, at two early attempts to locate and preserve the texts and traditions of the past.

An Early Library

In the iron age, the Assyrians of the north created an empire, at its height between 720 and 610 bce, that stretched as far west as Egypt. The state economy was now a predatory one, extracting labour and tribute in the form of food, animals, metal and craft items from a vast subject population.

The great Assyrian kings, who had been immigrants, acknowledged the southern region, Babylonia, as the centre of high culture and the last of them, Assurbanipal (668-627 bce), collected a library at his capital, Nineveh in the north. He made great efforts to gather tablets on history, epics, omen literature, astrology, hymns and poems. He sent his scribes south to find old tablets. Because scribes in the south were trained to read and write in schools where they all had to copy tablets by the dozen, there were towns in Babylonia where huge collections of tablets were created and acquired fame. And although Sumerian ceased to be spoken after about 1800 bce, it continued to be taught in schools, through vocabulary texts, sign lists, bilingual (Sumerian and Akkadian) tablets, etc. So even in 650 bce, cuneiform tablets written as far back as 2000 bce were intelligible – and Assurbanipal’s men knew where to look for early tablets or their copies.

Copies were made of important texts such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, the copier stating his name and writing the date. Some tablets ended with a reference to Assurbanipal:

‘I, Assurbanipal, king of the universe, king of Assyria, on whom the gods bestowed vast intelligence, who could acquire the recondite details of scholarly erudition, I wrote down on tablets the wisdom of the gods … And I checked and collated the tablets. I placed them for the future in the library of the temple of my god, Nabu, at Nineveh, for my life and the well-being of my soul, and to sustain the foundations of my royal throne…’

More important, there was cataloguing: a basket of tablets would have a clay label that read: ‘n number of tablets about exorcism, written by X’. Assurbanipal’s library had a total of some 1,000 texts, amounting to about 30,000 tablets, grouped according to subject.

And, an Early Archaeologist!

A man of the southern marshes, Nabopolassar, released Babylonia from Assyrian domination in 625 bce. His successors increased their territory and organised building projects at Babylon. From that time, even after the Achaemenids of Iran conquered Babylon in 539 bce and until 331 bce when Alexander conquered Babylon, Babylon was the premier city of the world, more than 850 hectares, with a triple wall, great palaces and temples, a ziggurat or stepped tower, and a processional way to the ritual centre. Its trading houses had widespread dealings and its mathematicians and astronomers made some new discoveries.

Nabonidus was the last ruler of independent Babylon. He writes that the god of Ur came to him in a dream and ordered him to appoint a priestess to take charge of the cult in that ancient town in the deep south. He writes:‘Because for a very long time the office of High Priestess had been forgotten, her characteristic features nowhere indicated, I bethought myself day after day …’

Then, he says, he found the stele of a very early king whom we today date to about 1150 bce and saw on that stele the carved image of the Priestess. He observed the clothing and the jewellery that was depicted. This is how he was able to dress his daughter for her consecration as Priestess.

On another occasion, Nabonidus’s men brought to him a broken statue inscribed with the name of Sargon, king of Akkad. (We know today that the latter ruled around 2370 bce.) Nabonidus, and indeed many intellectuals, had heard of this great king of remote times. Nabonidus felt he had to repair the statue. ‘Because of my reverence for the gods and respect for kingship,’ he writes, ‘I summoned skilled craftsmen, and replaced the head.’

Activity 4

Why do you think Assurbanipal and Nabonidus cherished early

Mesopotamian traditions?

Exercises

Answer in brief

1. Why do we say that it was not natural fertility and high levels of food production that were the causes of early urbanisation?

2. Which of the following were necessary conditions and which the causes, of early urbanisation, and which would you say were the outcome of the growth of cities:

(a) highly productive agriculture, (b) water transport, (c) the lack of metal and stone, (d) the division of labour, (e) the use of seals, (f) the military power of kings that made labour compulsory?

3. Why were mobile animal herders not necessarily a threat to town life?

4. Why would the early temple have been much like a house?

Answer in a short essay

5. Of the new institutions that came into being once city life had begun, which would have depended on the initiative of the king?

6. What do ancient stories tell us about the civilisation of Mesopotamia?