Table of Contents

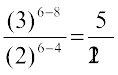

Chapter 8

Binomial Theorem

Mathematics is a most exact science and its conclusions are capable of

absolute proofs. – C.P. Steinmetz

8.1 Introduction

8.2 Binomial Theorem for Positive Integral Indices

Let us have a look at the following identities done earlier:

(a+ b)0 = 1 a + b ≠ 0

(a+ b)1 = a + b

(a+ b)2 = a2 + 2ab + b2

(a+ b)3 = a3 + 3a2b + 3ab2 + b3

(a+ b)4 = (a + b)3 (a + b) = a4 + 4a3b + 6a2b2 + 4ab3 + b4

In these expansions, we observe that

(i) The total number of terms in the expansion is one more than the index. For example, in the expansion of (a + b)2 , number of terms is 3 whereas the index of (a + b)2 is 2.

(ii) Powers of the first quantity ‘a’ go on decreasing by 1 whereas the powers of the second quantity ‘b’ increase by 1, in the successive terms.

(iii) In each term of the expansion, the sum of the indices of a and b is the same and is equal to the index of a + b.

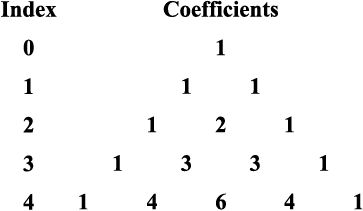

We now arrange the coefficients in these expansions as follows (Fig 8.1):

Fig 8.1

Do we observe any pattern in this table that will help us to write the next row? Yes we do. It can be seen that the addition of 1’s in the row for index 1 gives rise to 2 in the row for index 2. The addition of 1, 2 and 2, 1 in the row for index 2, gives rise to 3 and 3 in the row for index 3 and so on. Also, 1 is present at the beginning and at the end of each row. This can be continued till any index of our interest.

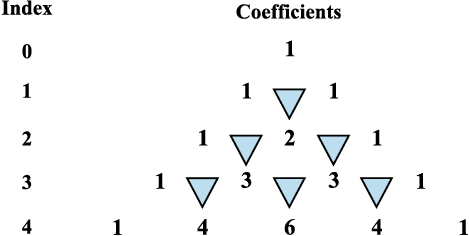

We can extend the pattern given in Fig 8.2 by writing a few more rows.

Fig 8.2

Pascal’s Triangle

The structure given in Fig 8.2 looks like a triangle with 1 at the top vertex and running down the two slanting sides. This array of numbers is known as Pascal’s triangle, after the name of French mathematician Blaise Pascal. It is also known as Meru Prastara by Pingla.

Expansions for the higher powers of a binomial are also possible by using Pascal’s triangle. Let us expand (2x + 3y)5 by using Pascal’s triangle. The row for index 5 is

1 5 10 10 5 1

Using this row and our observations (i), (ii) and (iii), we get

(2x + 3y)5 = (2x)5 + 5(2x)4 (3y) + 10(2x)3 (3y)2 +10 (2x)2 (3y)3 + 5(2x)(3y)4 +(3y)5

= 32x5 + 240x4y + 720x3y2 + 1080x2y3 + 810xy4 + 243y5.

Now, if we want to find the expansion of (2x + 3y)12, we are first required to get the row for index 12. This can be done by writing all the rows of the Pascal’s triangle till index 12. This is a slightly lengthy process. The process, as you observe, will become more difficult, if we need the expansions involving still larger powers.

We thus try to find a rule that will help us to find the expansion of the binomial for any power without writing all the rows of the Pascal’s triangle, that come before the row of the desired index.

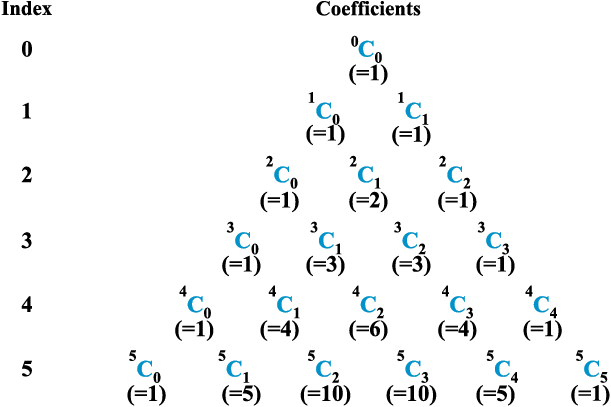

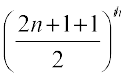

For this, we make use of the concept of combinations studied earlier to rewrite the numbers in the Pascal’s triangle. We know that  , 0 ≤ r ≤ n and n is a non-negative integer. Also, nC0 = 1 = nCn

, 0 ≤ r ≤ n and n is a non-negative integer. Also, nC0 = 1 = nCn

The Pascal’s triangle can now be rewritten as (Fig 8.3)

Fig 8.3 Pascal’s triangle

Observing this pattern, we can now write the row of the Pascal’s triangle for any index without writing the earlier rows. For example, for the index 7 the row would be

7C0 7C1 7C2 7C3 7C4 7C5 7C6 7C7.

Thus, using this row and the observations (i), (ii) and (iii), we have

(a + b)7 = 7C0 a7 + 7C1a6b + 7C2a5b2 + 7C3a4b3 + 7C4a3b4 + 7C5a2b5 + 7C6ab6 + 7C7b7

An expansion of a binomial to any positive integral index say n can now be visualised using these observations. We are now in a position to write the expansion of a binomial to any positive integral index.

8.2.1 Binomial theorem for any positive integer n,

(a + b)n = nC0an + nC1an–1b + nC2an–2 b2 + ...+ nCn – 1a.bn–1 + nCnbn

Proof The proof is obtained by applying principle of mathematical induction.

Let the given statement be

P(n) : (a + b)n = nC0an + nC1an – 1b + nC2an – 2b2 + ...+ nCn–1a.bn – 1 + nCnbn

For n = 1, we have

P (1) : (a + b)1 = 1C0a1 + 1C1b1 = a + b

Thus, P (1) is true.

Suppose P (k) is true for some positive integer k, i.e.

(a + b)k = kC0ak + kC1ak – 1b + kC2ak – 2b2 + ...+ kCkbk ... (1)

We shall prove that P(k + 1) is also true, i.e.,

(a + b)k + 1 = k + 1C0 ak + 1 + k + 1C1 akb + k + 1C2 ak – 1b2 + ...+ k + 1Ck+1 bk + 1

Now, (a + b)k + 1 = (a + b) (a + b)k

= (a + b) (kC0 ak + kC1ak – 1 b + kC2 ak – 2 b2 +...+ kCk – 1 abk – 1 + kCk bk)

[from (1)]

= kC0 ak + 1 + kC1 akb + kC2ak – 1b2 +...+ kCk – 1 a2bk – 1 + kCk abk + kC0 akb

+ kC1ak – 1b2 + kC2ak – 2b3+...+ kCk-1abk + kCkbk + 1

[by actual multiplication]

= kC0ak + 1 + (kC1+ kC0) akb + (kC2 + kC1)ak – 1b2 + ...

+ (kCk+ kCk–1) abk + kCkbk + 1 [grouping like terms]

= k + 1C0a k + 1 + k + 1C1akb + k + 1C2 ak – 1b2 +...+ k + 1Ckabk + k + 1Ck + 1 bk +1

(by using k + 1C0=1, kCr + kCr–1 = k + 1Cr and kCk = 1= k + 1Ck + 1)

Thus, it has been proved that P (k + 1) is true whenever P(k) is true. Therefore, by principle of mathematical induction, P(n) is true for every positive integer n.

We illustrate this theorem by expanding (x + 2)6:

(x + 2)6 = 6C0x6 + 6C1x5.2 + 6C2x422 + 6C3x3.23 + 6C4x2.24 + 6C5x.25 + 6C6.26.

= x6 + 12x5 + 60x4 + 160x3 + 240x2 + 192x + 64

Thus (x + 2)6 = x6 + 12x5 + 60x4 + 160x3 + 240x2 + 192x + 64.

Observations

1. The notation  stands for

stands for

nC0anb0 + nC1an–1b1 + ...+ nCran–rbr + ...+nCnan–nbn, where b0 = 1 = an–n.

Hence the theorem can also be stated as

.

.

2. The coefficients nCr occuring in the binomial theorem are known as binomial coefficients.

3. There are (n+1) terms in the expansion of (a+b)n, i.e., one more than the index.

4. In the successive terms of the expansion the index of a goes on decreasing by unity. It is n in the first term, (n–1) in the second term, and so on ending with zero in the last term. At the same time the index of b increases by unity, starting with zero in the first term, 1 in the second and so on ending with n in the last term.

5. In the expansion of (a+b)n, the sum of the indices of a and b is n + 0 = n in the first term, (n – 1) + 1 = n in the second term and so on 0 + n = n in the last term. Thus, it can be seen that the sum of the indices of a and b is n in every term of the expansion.

8.2.2 Some special cases In the expansion of (a + b)n,

(i) Taking a = x and b = – y, we obtain

(x – y)n = [x + (–y)]n

= nC0xn + nC1xn – 1(–y) + nC2xn–2(–y)2 + nC3xn–3(–y)3 + ... + nCn (–y)n

= nC0xn – nC1xn – 1y + nC2xn – 2y2 – nC3xn – 3y3 + ... + (–1)n nCn yn

Thus (x–y)n = nC0xn – nC1xn – 1 y + nC2xn – 2 y2 + ... + (–1)n nCn yn

Using this, we have (x–2y)5 = 5C0x5 – 5C1x4 (2y) + 5C2x3 (2y)2 – 5C3x2 (2y)3 +

5C4 x(2y)4 – 5C5(2y)5

= x5 –10x4y + 40x3y2 – 80x2y3 + 80xy4 – 32y5.

(ii) Taking a = 1, b = x, we obtain

(1 + x)n = nC0(1)n + nC1(1)n – 1x + nC2(1)n – 2 x2 + ... + nCnxn

= nC0 + nC1x + nC2x2 + nC3x3 + ... + nCnxn

Thus (1 + x)n = nC0 + nC1x + nC2x2 + nC3x3 + ... + nCnxn

In particular, for x = 1, we have

2n = nC0 + nC1 + nC2 + ... + nCn.

(iii) Taking a = 1, b = – x, we obtain

(1– x)n = nC0 – nC1x + nC2x2 – ... + (– 1)n nCnxn

In particular, for x = 1, we get

0 = nC0 – nC1 + nC2 – ... + (–1)n nCn

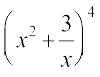

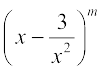

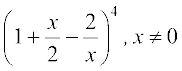

Example 1 Expand  , x ≠ 0

, x ≠ 0

Solution By using binomial theorem, we have

= 4C0(x2)4 + 4C1(x2)3

= 4C0(x2)4 + 4C1(x2)3  + 4C2(x2)2

+ 4C2(x2)2  + 4C3(x2)

+ 4C3(x2)  + 4C4

+ 4C4

= x8 + 4.x6 .  + 6.x4 .

+ 6.x4 .  + 4.x2.

+ 4.x2. +

+

= x8 + 12x5 + 54x2 +  .

.

Example 2 Compute (98)5.

Solution We express 98 as the sum or difference of two numbers whose powers are easier to calculate, and then use Binomial Theorem.

Write 98 = 100 – 2

Therefore, (98)5 = (100 – 2)5

= 5C0 (100)5 – 5C1 (100)4.2 + 5C2 (100)322

– 5C3 (100)2 (2)3 + 5C4 (100) (2)4 – 5C5 (2)5

= 10000000000 – 5 × 100000000 × 2 + 10 × 1000000 × 4 – 10 ×10000

× 8 + 5 × 100 × 16 – 32

= 10040008000 – 1000800032 = 9039207968.

Example 3 Which is larger (1.01)1000000 or 10,000?

Solution Splitting 1.01 and using binomial theorem to write the first few terms we have

(1.01)1000000 = (1 + 0.01)1000000

= 1000000C0 + 1000000C1(0.01) + other positive terms

= 1 + 1000000 × 0.01 + other positive terms

= 1 + 10000 + other positive terms

> 10000

Hence (1.01)1000000 > 10000

Example 4 Using binomial theorem, prove that 6n–5n always leaves remainder

1 when divided by 25.

Solution For two numbers a and b if we can find numbers q and r such that

a = bq + r, then we say that b divides a with q as quotient and r as remainder. Thus, in order to show that 6n – 5n leaves remainder 1 when divided by 25, we prove that

6n – 5n = 25k + 1, where k is some natural number.

We have

(1 + a)n = nC0 + nC1a + nC2a2 + ... + nCnan

For a = 5, we get

(1 + 5)n = nC0 + nC15 + nC252 + ... + nCn5n

i.e. (6)n = 1 + 5n + 52.nC2 + 53.nC3 + ... + 5n

i.e. 6n – 5n = 1+52 (nC2 + nC35 + ... + 5n-2)

or 6n – 5n = 1+ 25 (nC2 + 5 .nC3 + ... + 5n-2)

or 6n – 5n = 25k+1 where k = nC2 + 5 .nC3 + ... + 5n–2.

This shows that when divided by 25, 6n – 5n leaves remainder 1.

Exercise 8.1

Expand each of the expressions in Exercises 1 to 5.

1. (1–2x)5 2.  3. (2x – 3)6

3. (2x – 3)6

4.  5.

5.

Using binomial theorem, evaluate each of the following:

6. (96)3 7. (102)5 8. (101)4

9. (99)5

10. Using Binomial Theorem, indicate which number is larger (1.1)10000 or 1000.

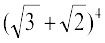

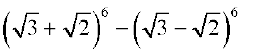

11. Find (a + b)4 – (a – b)4. Hence, evaluate  –

–  .

.

12. Find (x + 1)6 + (x – 1)6. Hence or otherwise evaluate ( + 1)6 + (

+ 1)6 + ( – 1)6.

– 1)6.

13. Show that 9n+1 – 8n – 9 is divisible by 64, whenever n is a positive integer.

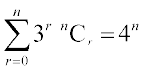

14. Prove that  .

.

8.3 General and Middle Terms

1. In the binomial expansion for (a + b)n, we observe that the first term is

nC0an, the second term is nC1an–1b, the third term is nC2an–2b2, and so on. Looking at the pattern of the successive terms we can say that the (r + 1)th term is

nCran–rbr. The (r + 1)th term is also called the general term of the expansion

(a + b)n. It is denoted by Tr+1. Thus Tr+1 = nCr an–rbr.

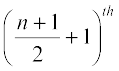

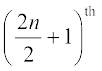

2. Regarding the middle term in the expansion (a + b)n, we have

(i) If n is even, then the number of terms in the expansion will be n + 1. Since n is even so n + 1 is odd. Therefore, the middle term is  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  term.

term.

For example, in the expansion of (x + 2y)8, the middle term is  i.e., 5th term.

i.e., 5th term.

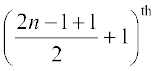

(ii) If n is odd, then n +1 is even, so there will be two middle terms in the expansion, namely,  term and

term and  term. So in the expansion

term. So in the expansion

(2x – y)7, the middle terms are  , i.e., 4th and

, i.e., 4th and  , i.e., 5th term.

, i.e., 5th term.

3. In the expansion of  , where x ≠ 0, the middle term is

, where x ≠ 0, the middle term is  , i.e., (n + 1)th term, as 2n is even.

, i.e., (n + 1)th term, as 2n is even.

It is given by 2nCnxn  = 2nCn (constant).

= 2nCn (constant).

This term is called the term independent of x or the constant term.

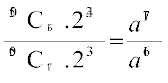

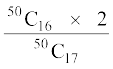

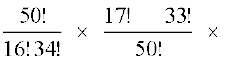

Example 5 Find a if the 17th and 18th terms of the expansion (2 + a)50 are equal.

Solution The (r + 1)th term of the expansion (x + y)n is given by Tr + 1 = nCrxn–ryr.

For the 17th term, we have, r + 1 = 17, i.e., r = 16

Therefore, T17 = T16 + 1 = 50C16 (2)50 – 16 a16

= 50C16 234 a16.

Similarly, T18 = 50C17 233 a17

Given that T17 = T18

So 50C16 (2)34 a16 = 50C17 (2)33 a17

Therefore

i.e., a =  =

=  2 = 1

2 = 1

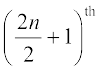

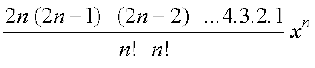

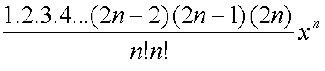

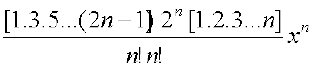

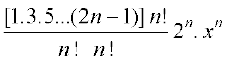

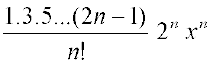

Example 6 Show that the middle term in the expansion of (1+x)2n is  2n xn, where n is a positive integer.

2n xn, where n is a positive integer.

Solution As 2n is even, the middle term of the expansion (1 + x)2n is  , i.e., (n + 1)th term which is given by,

, i.e., (n + 1)th term which is given by,

Tn+1 = 2nCn(1)2n – n(x)n = 2nCnxn =

=

=

=  xn

xn

=

=

=

Example 7 Find the coefficient of x6y3 in the expansion of (x + 2y)9.

Solution Suppose x6y3 occurs in the (r + 1)th term of the expansion (x + 2y)9.

Now Tr+1 = 9Cr x9 – r (2y)r = 9Cr 2 r . x9 – r . y r .

Comparing the indices of x as well as y in x6y3 and in Tr + 1 , we get r = 3.

Thus, the coefficient of x6y3 is

9C3 2 3 =  =

=  = 672.

= 672.

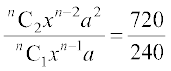

Example 8 The second, third and fourth terms in the binomial expansion (x + a)n are 240, 720 and 1080, respectively. Find x, a and n.

Solution Given that second term T2 = 240

We have T2 = nC1xn – 1 . a

So nC1xn–1 . a = 240 ... (1)

Similarly nC2xn–2 a2 = 720 ... (2)

and nC3xn–3 a3 = 1080 ... (3)

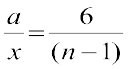

Dividing (2) by (1), we get

i.e.,

i.e.,

or  ... (4)

... (4)

Dividing (3) by (2), we have

... (5)

... (5)

From (4) and (5),

. Thus, n = 5

. Thus, n = 5

Hence, from (1), 5x4a = 240, and from (4),

Solving these equations for a and x, we get x = 2 and a = 3.

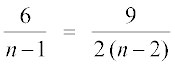

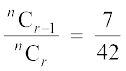

Example 9 The coefficients of three consecutive terms in the expansion of (1 + a)n are in the ratio1: 7 : 42. Find n.

Solution Suppose the three consecutive terms in the expansion of (1 + a)n are

(r – 1)th, rth and (r + 1)th terms.

The (r – 1)th term is nCr – 2 ar – 2, and its coefficient is nCr – 2. Similarly, the coefficients of rth and (r + 1)th terms are nCr – 1 and nCr , respectively.

Since the coefficients are in the ratio 1 : 7 : 42, so we have,

, i.e., n – 8r + 9 = 0 ... (1)

, i.e., n – 8r + 9 = 0 ... (1)

and  , i.e., n – 7r + 1 = 0 ... (2)

, i.e., n – 7r + 1 = 0 ... (2)

Solving equations(1) and (2), we get, n = 55.

Exercise 8.2

Find the coefficient of

1. x5 in (x + 3)8 2. a5b7 in (a – 2b)12 .

Write the general term in the expansion of

3. (x2 – y)6 4. (x2 – yx)12, x ≠ 0.

5. Find the 4th term in the expansion of (x – 2y)12.

6. Find the 13th term in the expansion of  , x

, x  0.

0.

Find the middle terms in the expansions of

7.  8.

8.  .

.

9. In the expansion of (1 + a)m+n, prove that coefficients of am and an are equal.

10. The coefficients of the (r – 1)th, rth and (r + 1)th terms in the expansion of (x + 1)n are in the ratio 1 : 3 : 5. Find n and r.

11. Prove that the coefficient of xn in the expansion of (1 + x)2n is twice the coefficient of xn in the expansion of (1 + x)2n – 1.

12. Find a positive value of m for which the coefficient of x2 in the expansion

(1 + x)m is 6.

Miscellaneous Examples

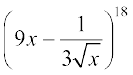

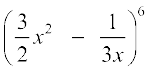

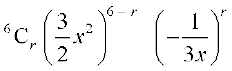

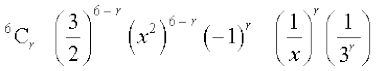

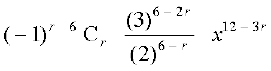

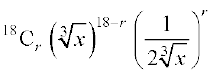

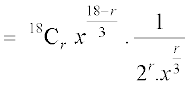

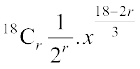

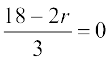

Example 10 Find the term independent of x in the expansion of  .

.

Solution We have Tr + 1 =

=

=

The term will be independent of x if the index of x is zero, i.e., 12 – 3r = 0. Thus, r = 4

Hence 5th term is independent of x and is given by (– 1)4 6 C4  .

.

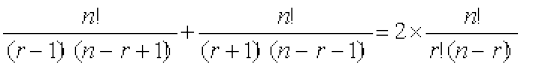

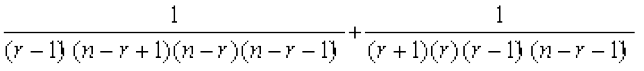

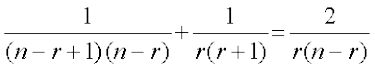

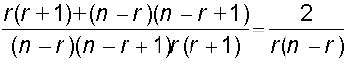

Example 11 If the coefficients of ar – 1, ar and ar + 1 in the expansion of (1 + a)n are in arithmetic progression, prove that n2 – n(4r + 1) + 4r2 – 2 = 0.

Solution The (r + 1)th term in the expansion is nCrar. Thus it can be seen that ar occurs in the (r + 1)th term, and its coefficient is nCr. Hence the coefficients of ar – 1, ar and

ar + 1 are nCr – 1, nCr and nCr + 1, respectively. Since these coefficients are in arithmetic progression, so we have, nCr – 1+ nCr + 1 = 2.nCr. This gives

i.e.

or

i.e.  ,

,

or

or r(r + 1) + (n – r) (n – r + 1) = 2 (r + 1) (n – r + 1)

or r2 + r + n2 – nr + n – nr + r2 – r = 2(nr – r2 + r + n – r + 1)

or n2 – 4nr – n + 4r2 – 2 = 0

i.e., n2 – n (4r + 1) + 4r2 – 2 = 0

Example 12 Show that the coefficient of the middle term in the expansion of (1 + x)2n is equal to the sum of the coefficients of two middle terms in the expansion of (1 + x)2n – 1.

Solution As 2n is even so the expansion (1 + x)2n has only one middle term which is  i.e., (n + 1)th term.

i.e., (n + 1)th term.

The (n + 1)th term is 2nCnxn. The coefficient of xn is 2nCn

Similarly, (2n – 1) being odd, the other expansion has two middle terms,

and

and  i.e., nth and (n + 1)th terms. The coefficients of these terms are 2n – 1Cn – 1 and 2n – 1Cn, respectively.

i.e., nth and (n + 1)th terms. The coefficients of these terms are 2n – 1Cn – 1 and 2n – 1Cn, respectively.

Now

2n – 1Cn – 1 + 2n – 1Cn= 2nCn [As nCr – 1+ nCr = n + 1Cr]. as required.

Example 13 Find the coefficient of a4 in the product (1 + 2a)4 (2 – a)5 using binomial theorem.

Solution We first expand each of the factors of the given product using Binomial Theorem. We have

(1 + 2a)4 = 4C0 + 4C1 (2a) + 4C2 (2a)2 + 4C3 (2a)3 + 4C4 (2a)4

= 1 + 4 (2a) + 6(4a2) + 4 (8a3) + 16a4.

= 1 + 8a + 24a2 + 32a3 + 16a4

and (2 – a)5 = 5C0 (2)5 – 5C1 (2)4 (a) + 5C2 (2)3 (a)2 – 5C3 (2)2 (a)3

+ 5C4 (2) (a)4 – 5C5 (a)5

= 32 – 80a + 80a2 – 40a3 + 10a4 – a5

Thus (1 + 2a)4 (2 – a)5

= (1 + 8a + 24a2 + 32a3+ 16a4) (32 –80a + 80a2– 40a3 + 10a4– a5)

The complete multiplication of the two brackets need not be carried out. We write only those terms which involve a4. This can be done if we note that ar. a4 – r = a4. The terms containing a4 are

1 (10a4) + (8a) (–40a3) + (24a2) (80a2) + (32a3) (– 80a) + (16a4) (32) = – 438a4

Thus, the coefficient of a4 in the given product is – 438.

Example 14 Find the rth term from the end in the expansion of (x + a)n.

Solution There are (n + 1) terms in the expansion of (x + a)n. Observing the terms we can say that the first term from the end is the last term, i.e., (n + 1)th term of the expansion and n + 1 = (n + 1) – (1 – 1). The second term from the end is the nth term of the expansion, and n = (n + 1) – (2 – 1). The third term from the end is the (n – 1)th term of the expansion and n – 1 = (n + 1) – (3 – 1) and so on. Thus rth term from the end will be term number (n + 1) – (r – 1) = (n – r + 2) of the expansion. And the

(n – r + 2)th term is nCn – r + 1 xr – 1 an – r + 1.

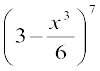

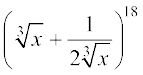

Example 15 Find the term independent of x in the expansion of  , x > 0.

, x > 0.

Solution We have Tr + 1 =

=

=

Since we have to find a term independent of x, i.e., term not having x, so take  . We get r = 9. The required term is 18C9

. We get r = 9. The required term is 18C9  .

.

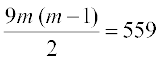

Example 16 The sum of the coefficients of the first three terms in the expansion of  , x ≠ 0, m being a natural number, is 559. Find the term of the expansion containing x3.

, x ≠ 0, m being a natural number, is 559. Find the term of the expansion containing x3.

Solution The coefficients of the first three terms of  are mC0, (–3) mC1

are mC0, (–3) mC1

and 9 mC2. Therefore, by the given condition, we have

mC0 –3 mC1+ 9 mC2 = 559, i.e., 1 – 3m +

which gives m = 12 (m being a natural number).

Now Tr + 1 = 12Cr x12 – r  = 12Cr (– 3)r . x12 – 3r

= 12Cr (– 3)r . x12 – 3r

Since we need the term containing x3, so put 12 – 3r = 3 i.e., r = 3.

Thus, the required term is 12C3 (– 3)3 x3, i.e., – 5940 x3.

Example 17 If the coefficients of (r – 5)th and (2r – 1)th terms in the expansion of

(1 + x)34 are equal, find r.

Solution The coefficients of (r – 5)th and (2r – 1)th terms of the expansion (1 + x)34 are 34Cr – 6 and 34C2r – 2, respectively. Since they are equal so 34Cr – 6 = 34C2r – 2

Therefore, either r – 6 = 2r – 2 or r–6 = 34 – (2r – 2)

[Using the fact that if nCr = nCp, then either r = p or r = n – p]

So, we get r = – 4 or r = 14. r being a natural number, r = – 4 is not possible.

So, r = 14.

Miscellaneous Exercise on Chapter 8

1. Find a, b and n in the expansion of (a + b)n if the first three terms of the expansion are 729, 7290 and 30375, respectively.

2. Find a if the coefficients of x2 and x3 in the expansion of (3 + ax)9 are equal.

3. Find the coefficient of x5 in the product (1 + 2x)6 (1 – x)7 using binomial theorem.

4. If a and b are distinct integers, prove that a – b is a factor of an – bn, whenever n is a positive integer.

[Hint write an = (a – b + b)n and expand]

5. Evaluate  .

.

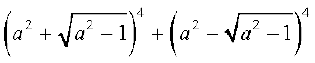

6. Find the value of  .

.

7. Find an approximation of (0.99)5 using the first three terms of its expansion.

8. Find n, if the ratio of the fifth term from the beginning to the fifth term from the end in the expansion of  is

is  .

.

9. Expand using Binomial Theorem  .

.

10. Find the expansion of (3x2 – 2ax + 3a2)3 using binomial theorem.

SUMMARY

The expansion of a binomial for any positive integral n is given by Binomial Theorem, which is (a + b)n = nC0an + nC1an – 1b + nC2an – 2b2 + ...+

nCn – 1a.bn – 1 + nCnbn.

The coefficients of the expansions are arranged in an array. This array is called Pascal’s triangle.

The general term of an expansion (a + b)n is Tr + 1 = nCran – r. br.

In the expansion (a + b)n, if n is even, then the middle term is the  term. If n is odd, then the middle terms are

term. If n is odd, then the middle terms are  and

and  terms.

terms.

HISTORICAL NOTE

The ancient Indian mathematicians knew about the coefficients in the expansions of (x + y)n, 0 ≤ n ≤7. The arrangement of these coefficients was in the form of a diagram called Meru-Prastara, provided by Pingla in his book Chhanda shastra (200B.C.). This triangular arrangement is also found in the work of Chinese mathematician Chu-shi-kie in 1303. The term binomial coefficients was first introduced by the German mathematician, Michael Stipel (1486-1567) in approximately 1544. Bombelli (1572) also gave the coefficients in the expansion of (a + b)n, for n = 1,2 ...,7 and Oughtred (1631) gave them for n = 1, 2,..., 10. The arithmetic triangle, popularly known as Pascal’s triangle and similar to the Meru-Prastara of Pingla was constructed by the French mathematician Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) in 1665.

The present form of the binomial theorem for integral values of n appeared in Trate du triange arithmetic, written by Pascal and published posthumously in 1665.