Table of Contents

Chapter 3

The Bases of Human Behaviour

After reading this chapter, you would be able to

• understand the evolutionary nature of human behaviour,

• relate the functions of nervous system and endocrine system to behaviour,

• explain the role of genetic factors in determining behaviour,

• understand the role of culture in shaping human behaviour,

• describe the processes of enculturation, socialisation, and acculturation, and

• relate biological and socio-cultural factors in understanding human behaviour.

There are one hundred and ninety-three species of monkeys and apes. One-hundred and ninety-two of them are covered with hair. The exception is the naked ape self-named, homo-sapiens.

– Desmond Morris

Contents

Introduction

Evolutionary Perspective

Biological and Cultural Roots

Biological Basis of Behaviour

Neurons

Structure and Functions of Nervous System and Endocrine System and their Relationship with Behaviour and Experience

The Nervous System

The Endocrine System

Heredity: Genes and Behaviour

Cultural Basis : Socio-Cultural Shaping of Behaviour

Concept of Culture

Biological and Cultural Transmission (Box 3.1)

Enculturation

Socialisation

Acculturation

Key Terms

Summary

Review Questions

Project Ideas

Introduction

Human beings, the homo sapiens, are the most developed organisms among all creatures on this earth. Their ability to walk upright, larger brain size relative to body weight, and the proportion of specialised brain tissues make them distinct from other species. These features have evolved through millions of years and have enabled them to engage in several complex behaviours. Scientists have attempted to study the relationship of complex human behaviour with the processes of the nervous system, particularly the brain. They have tried to discover the neural basis of thoughts, feelings, and actions. By understanding the biological aspects of human beings, you will be able to appreciate how the brain, environment and behaviour interact to generate unique forms of behaviour. In this chapter, we begin with a general description of the nervous system in an evolutionary perspective. You will also study the structure and functions of the nervous system. You will learn about the endocrine system, and its influence on human behaviour. Later in this chapter, you will also study the notion of culture and show its relevance to the understanding of behaviour. This will be followed by an analysis of the processes of enculturation, socialisation, and acculturation.

Evolutionary Perspective

You must have observed that people differ with respect to their physical and psychological characteristics. The uniqueness of individuals results from the interaction of their genetic endowments and environmental demands.

In this world, there are millions of different species of organisms differing in a variety of ways. Biologists believe that these species were not always like this; they have evolved to their present form from their pre-existing forms. It is estimated that the characteristics of modern human beings developed some 2,00,000 years ago as a result of their continuous interaction with the environment.

Evolution refers to gradual and orderly biological changes that result in a species from their pre-existing forms in response to the changing adaptational demands of their environment. Physiological as well as behavioural changes that occur due to the evolutionary process are so slow that they become visible after hundreds of generations. Evolution occurs through the process of natural selection. You know that members of each species vary greatly in their physical structure and behaviour. The traits or characteristics that are associated with high rate of survival and reproduction of those species are the most likely ones to be passed on to the next generations. When repeated generation after generation, natural selection leads to the evolution of new species that are more effectively adapted to their particular environment. This is very similar to the selective breeding of horses or other animals these days. Breeders select the fittest and the fastest male and female horses from their stock, and promote them for selective breeding so that they can get the fittest horses. Fitness is the ability of an organism to survive and contribute its genes to the next generation.

Three important features of modern human beings differentiate them from their ancestors: (i) a bigger and developed brain with increased capacity for cognitive behaviours like perception, memory, reasoning, problem solving, and use of language for communication, (ii) ability to walk upright on two legs, and (iii) a free hand with a workable opposing thumb. These features have been with us for several thousand years.

Our behaviours are highly complex and more developed than those of other species because we have got a large and highly developed brain. Human brain development is evidenced by two facts. Firstly, the weight of the brain is about 2.35 per cent of the total body weight, and it is the highest among all species (in elephant it is 0.2 per cent). Secondly, the human cerebrum is more evolved than other parts of the brain.

These evolutions have resulted due to the influence of environmental demands. Some behaviours play an obvious role in evolution. For example, the ability to find food, avoid predators, and defend one’s young are the objectives related to the survival of the organisms as well as their species. The biological and behavioural qualities, which are helpful in meeting these objectives, increase an organism’s ability to pass it on to the future generation through its genes. The environmental demands lead to biological and behavioural changes over a long period of time.

Biological and Cultural Roots

An important determinant of our behaviour is the biological structures that we have inherited from our ancestors in the form of developed body and brain. The importance of such a biological bases becomes obvious when we observe cases in which brain cells have been destroyed by any disease, use of drug or an accident. Such cases develop various kinds of physical and behavioural disabilities. Many children develop mental retardation and other abnormal symptoms due to transmission of a faulty gene from the parents.

As human beings, we not only share a biological system, but also certain cultural systems. These systems are quite varied across human populations. All of us negotiate our lives with the culture in which we are born and brought up. Culture provides us with different experiences and opportunities of learning by putting us in a variety of situations or placing different demands on our lives. Such experiences, opportunities and demands also influence our behaviour considerably. These influences become more potent and visible as we move from infancy to later years of life. Thus, besides biological bases, there are cultural bases of behaviour also. You will learn about the role of culture in behaviour at a later point in this chapter.

Biological Basis of Behaviour

Neurons

Neuron is the basic unit of our nervous system. Neurons are specialised cells, which possess the unique property of converting various forms of stimuli into electrical impulses. They are also specialised for reception, conduction and transmission of information in the form of electrochemical signals. They receive information from sense organs or from other adjacent neurons, carry them to the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), and bring motor information from the central nervous system to the motor organs (muscles and glands).

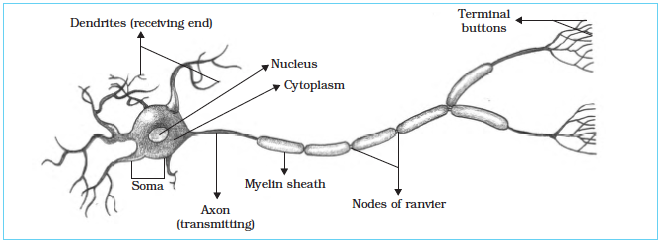

Nearly 12 billion neurons are found in the human nervous system. They are of many types and vary considerably in shape, size, chemical composition, and function. Despite these differences, they share three fundamental components, i.e. soma, dendrites, and axon.

The soma or cell body is the main body of the nerve cell. It contains the nucleus of the cell as well as other structures common to living cells of all types (Figure 3.1). The genetic material of the neuron is stored inside the nucleus and it becomes actively engaged during cell reproduction and protein synthesis. The soma also contains most of the cytoplasm (cell-fluid) of the neuron. Dendrites are the branch-like specialised structures emanating from the soma. They are the receiving ends of a neuron. Their function is to receive the incoming neural impulses from adjacent neurons or directly from the sense organs. On dendrites are found specialised receptors, which become active when a signal arrives in electrochemical or biochemical form. The received signals are passed on to soma and then to axon so that the information is relayed to another neuron or to muscles. The axon conducts the information along its length, which can be several feet in the spinal cord and less than a millimeter in the brain. At the terminal point the axon branches into small structures, called terminal buttons. These buttons have the capability for transmitting information to another neuron, gland and muscle. Neurons generally conduct information in one direction, that is, from the dendrites through soma and axon to the terminal buttons.

Fig.3.1 : The Structure of Neuron

The conduction of information from one place to another in the nervous system is done through nerves, which are bundles of axons. Nerves are mainly of two types: sensory and motor. Sensory nerves, also called afferent nerves, carry information from sense organs to central nervous system. On the other hand, motor nerves, also called efferent nerves, carry information from central nervous system to muscles or glands. A motor nerve conducts neural commands which direct, control, and regulates our movements and other responses. There are some mixed nerves also, but sensory and motor fibers in these nerves are separate.

Nerve Impulse

Information travels within the nervous system in the form of a nerve impulse. When stimulus energy comes into contact with receptors, electrical changes in the nerve potential start. Nerve potential is a sudden change in the electrical potential of the surface of a neuron. When the stimulus energy is relatively weak, the electrical changes are so small that the nerve impulse is not generated, and we do not feel that stimulus. If the stimulus energy is relatively strong, electrical impulses are generated and conducted towards the central nervous system. The strength of the nerve impulse, however, does not depend on the strength of the stimulus that started the impulse. The nerve fibers work according to the “all or none principle”, which means that they either respond completely or do not respond at all. The strength of the nerve impulse remains constant along the nerve fiber.

Synapse

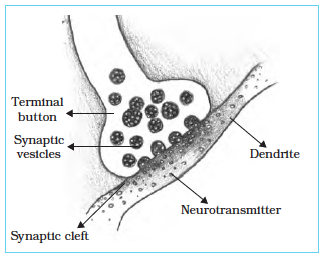

Information is transmitted from one place to another within the nervous system in the form of a neural impulse. A single neuron can carry a neural impulse up to a distance covered by the length of its axon. When the impulse is to be conducted to a distant part of the body, a number of neurons participate in the process. In this process, one neuron faithfully relays the information to a neighboring neuron. The axon tip of a preceding neuron make functional connections or synapse with dendrites of the other neuron. A neuron is never physically connected with another neuron; rather there is a small gap between the two. This gap is known as synaptic cleft. The neural impulse from one neuron is transmitted by a complex synaptic transmission process to another neuron. The conduction of neural impulse in the axon is electrochemical, while the nature of synaptic transmission is chemical (Figure 3.2). The chemical substances are known as neurotransmitters.

Fig.3.2 : Transmission of Nerve Impulse through Synapse

Structure and Functions of Nervous System and Endocrine System and their Relationship with Behaviour and Experience

Since our biological structures play an important role in organisation and execution of behaviour, we shall look at these structures in some detail. In particular, you will read about the nervous system and the endocrine system, which work together in giving a shape to human behaviour and experience.

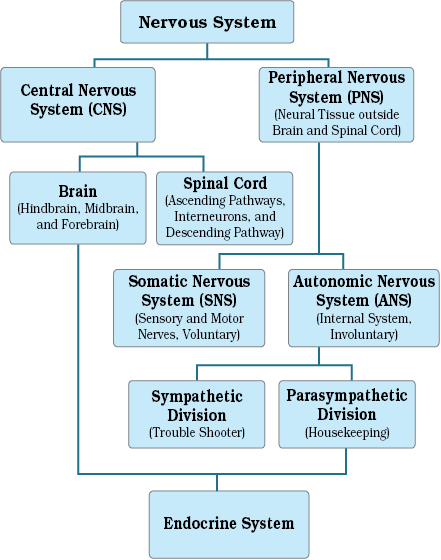

The Nervous System

Human nervous system is the most complex and most developed of all living creatures. Though the nervous system functions as a whole, for the ease of study, we can divide it into many parts depending on its location or functions. Based on location, the nervous system can be divided into two parts: Central Nervous System (CNS) and Peripheral Nervous System (PNS). The part of the nervous system found inside the hard bony cases (cranium and backbone) is classified as CNS. Brain and spinal cord are the organs of this system. The parts of the nervous system other than central nervous system are placed in the PNS. PNS can be further classified into Somatic and Autonomic nervous system. Somatic nervous system is concerned with voluntary actions, while the autonomic nervous system performs functions on which we have no voluntary control. The organisation of the nervous system is schematically presented in Figure 3.3.

Fig.3.3 : Schematic Representation of the Nervous System

The Peripheral Nervous System

The PNS is composed of all the neurons and nerve fibers that connect the CNS to the rest of the body. The PNS is divided into Somatic Nervous System and Autonomic Nervous System. The autonomic nervous system is further divided into Sympathetic and Parasympathetic systems. The PNS provides information to the CNS from sensory receptors (eyes, ears, skin, etc.) and relays back motor commands from the brain to the muscles and glands.

The Somatic Nervous System

This system consists of two types of nerves, called cranial nerves and spinal nerves. There are twelve sets of cranial nerves which either emanate from or reach different locations of the brain. There are three types of cranial nerves - sensory, motor, and mixed. Sensory nerves collect sensory information from receptors of the head region (vision, audition, smell, taste, touch, etc.) and carry them to the brain. The motor nerves carry motor impulses originating from the brain to muscles of the head region. For example, movements of the eyeballs are controlled by motor cranial nerves. Mixed nerves have both sensory and motor fibers, which conduct sensory and motor information to and from the brain.

There are thirty one sets of spinal nerves coming out of or reaching to the spinal cord. Each set has sensory and motor nerves. Spinal nerves have two functions. The sensory fibers of the spinal nerves collect sensory information from all over the body (except the head region) and send them to the spinal cord from where they are then carried out to the brain. In addition, motor impulses coming down from the brain are sent to the muscles by the motor fibers of the spinal nerves.

The Autonomic Nervous System

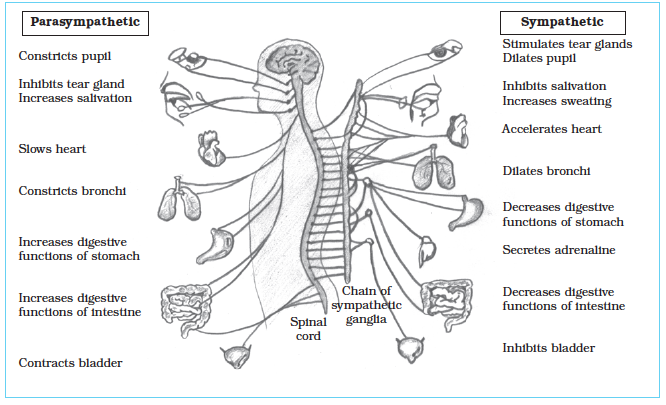

This system governs activities which are normally not under direct control of individuals. It controls such internal functions as breathing, blood circulation, salivation, stomach contraction, and emotional reactions (Figure 3.4). These activities of the autonomic system are under the control of different structures of the brain.

Fig.3.4 : The Functions of the Autonomic Nervous System

The Autonomic Nervous System has two divisions: Sympathetic division and Parasympathetic division. Although the effect of one division is opposite to the effect of the other, both work together to maintain a state of equilibrium. The sympathetic division deals with emergencies when the action must be quick and powerful, such as in situations of fight or flight. During this period, the digestion stops, blood flows from internal organs to the muscles, and breathing rate, oxygen supply, heart rate, and blood sugar level increases.

The Parasympathetic division is mainly concerned with conservation of energy. It monitors the routine functions of the internal system of the body. When the emergency is over, the parasympathetic division takes over; it decelerates the sympathetic activation and calms down the individual to a normal condition. As a result all body functions like heart beat, breathing, and blood flow return to their normal levels.

The Central Nervous System

The central nervous system (CNS) is the centre of all neural activity. It integrates all incoming sensory information, performs all kinds of cognitive activities, and issues motor commands to muscles and glands. The CNS comprises of the (a) brain and (b) spinal cord. You will now read about the functions of the major parts of the brain and for what behaviours is each part responsible.

The Brain and Behaviour

It is believed that the human brain has evolved over millions of years from the brains of lower animals, and this evolutionary process still continues. We can examine the levels of structures in the brain, from its earliest to the most recent form in the process of evolution. The limbic system, brain stem and cerebellum are the oldest structures, while Cerebral Cortex is the latest development in the course of evolution. An adult brain weighs about 1.36 kg and contains around 100 billion neurons. However, the most amazing thing about the brain is not its number of neurons but its ability to guide human behaviour and thought. The brain is organised into structures and regions that perform specific functions. Brain scanning reveals that while some mental functions are distributed among different areas of the brain, many activities are localised also. For example, the occipital lobe of the brain is a specialised area for vision.

Activity 3.1

Ask some students to make small slips of paper and write names of the parts of the nervous system on them. Put the slips together in a bowl and ask the students from the class to pick one slip each. Give them a few minutes and ask them to learn the location and function of the part mentioned in the slip. Each student is to then come forward and introduce him/herself as that part and explain the location and functions of that part.

Structure of the Brain

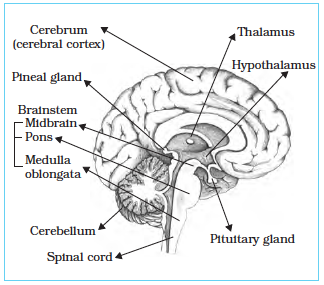

For the convenience of study, the brain can be divided into three parts: Hindbrain, Midbrain and Forebrain (Figure 3.5).'

Fig.3.5 : Structure of the Brain

Hindbrain

This part of the brain consists of the following structures:

Medulla Oblongata : It is the lowest part of the brain that exists in continuation of the spinal cord. It contains neural centres, which regulate basic life supporting activities like breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure. This is why medulla is known as the vital centre of the brain. It has some centres of autonomic activities also.

Pons : It is connected with medulla on one side and with the midbrain on the other. A nucleus (neural centre) of pons receives auditory signals relayed by our ears. It is believed that pons is involved in sleep mechanism, particularly the sleep characterised by dreaming. It contains nuclei affecting respiratory movement and facial expressions also.

Cerebellum : This highly developed part of the hindbrain can be easily recognised by its wrinkled surface. It maintains and controls posture and equilibrium of the body. Its main function is coordination of muscular movements. Though the motor commands originate in the forebrain, the cerebellum receives and coordinates them to relay to the muscles. It also stores the memory of movement patterns so that we do not have to concentrate on how to walk, dance, or ride a bicycle.

Midbrain

The midbrain is relatively small in size and it connects the hindbrain with the forebrain. A few neural centres related to some special reflexes and visual and auditory sensations are found here. An important part of midbrain, known as Reticular Activating System (RAS), is responsible for our arousal. It makes us alert and active by regulating sensory inputs. It also helps us in selecting information from the environment.

Forebrain

It is considered to be the most important part of the brain because it performs all cognitive, emotional, and motor activities. We will discuss four major parts of the forebrain: hypothalamus, thalamus, limbic system, and cerebrum.

Hypothalamus : The hypothalamus is one of the smallest structures in the brain, but plays a vital role in our behaviour. It regulates physiological processes involved in emotional and motivational behaviour, such as eating, drinking, sleeping, temperature regulation, and sexual arousal. It also regulates and controls the internal environment of the body (e.g., heart rate, blood pressure, temperature) and regulates the secretion of hormones from various endocrine glands.

Thalamus : It consists of an egg-shaped cluster of neurons situated on the ventral (upper) side of the hypothalamus. It is like a relay station that receives all incoming sensory signals from sense organs and sends them to appropriate parts of the cortex for processing. It also receives all outgoing motor signals coming from the cortex and sends them to appropriate parts of the body.

The Limbic System : This system is composed of a group of structures that form part of the old mammalian brain. It helps in maintaining internal homeostasis by regulating body temperature, blood pressure, and blood sugar level. It has close links with the hypothalamus. Besides hypothalamus, the limbic system comprises the Hippocampus and Amygdala. The hippocampus plays an important role in long-term memory. The amygdala plays an important role in emotional behaviour.

The Cerebrum : Also known as Cerebral Cortex, this part regulates all higher levels of cognitive functions, such as attention, perception, learning, memory, language behaviour, reasoning, and problem solving. The cerebrum makes two-third of the total mass of the human brain. Its thickness varies from 1.5 mm to 4 mm, which covers the entire surface of the brain and contains neurons, neural nets, and bundles of axons. All these make it possible for us to perform organised actions and create images, symbols, associations, and memories.

The cerebrum is divided into two symmetrical halves, called the Cerebral Hemispheres. Although the two hemispheres appear identical, functionally one hemisphere usually dominates the other. For example, the left hemisphere usually controls language behaviour. The right hemisphere is usually specialised to deal with images, spatial relationships, and pattern recognition. These two hemispheres are connected by a white bundle of myelinated fibers, called Corpus Callosum that carries messages back and forth between the hemispheres.

Cerebral cortex has also been divided into four lobes - Frontal lobe, Parietal lobe, Temporal lobe, and Occipital lobe. The Frontal lobe is mainly concerned with cognitive functions, such as attention, thinking, memory, learning, and reasoning, but it also exerts inhibitory effects on autonomic and emotional responses. The Parietal lobe is mainly concerned with cutaneous sensations and their coordination with visual and auditory sensations. The Temporal lobe is primarily concerned with the processing of auditory information. Memory for symbolic sounds and words resides here. Understanding of speech and written language depends on this lobe. The Occipital lobe is mainly concerned with visual information. It is believed that interpretation of visual impulses, memory for visual stimuli and colour visual orientation is performed by this lobe.

Physiologists and psychologists have tried to identify specific functions associated with specific brain structures. They have found that no activity of the brain is performed only by a single part of the cortex. Normally, other parts are involved, but it is also correct that there is some localisation of functions, i.e. for a particular function, a particular part of the cortex plays a more important role than the other parts. For example, if you are driving a car, you see the road and other vehicles by the function of your occipital lobe, hear the horns by the function of your temporal lobe, do many motor activities controlled by parietal lobe, and make decisions by the help of frontal lobe. The whole brain acts as a well coordinated unit in which different parts contribute their functions separately.

Spinal Cord

The spinal cord is a long rope-like collection of nerve fibers, which run along the full length inside the spine. Its one end is connected with the medulla of the brain and another is free at the tail end. Its structure all along its length is similar. The butterfly shaped mass of grey matter present in the centre of the spinal cord contains association neurons and other cells. Surrounding the grey matter is the white matter of the spinal cord, which is composed of the ascending and descending neural tracts. These tracts (collections of nerve fibers) connect the brain with the rest of the body. The spinal cord plays the role of a huge cable, which exchanges innumerable messages with the CNS. There are two main functions of the spinal cord. Firstly, it carries sensory impulses coming from the lower parts of the body to the brain; and motor impulses originating from the brain to all over the body. Secondly, it performs some simple reflexes that do not involve the brain. Simple reflexes involve a sensory nerve, a motor nerve, and the association neurons of the grey matter of the spinal cord.

Reflex Action

A reflex is an involuntary action that occurs very quickly after its specific kind of stimulation. The reflex action takes place automatically without conscious decision of the brain. Reflex actions are inherited in our nervous system through evolutionary processes, for example, the eye-blinking reflex. Whenever any object suddenly comes near our eyes, our eyelids blink. Reflexes serve to protect the organism from potential threats and preserve life. Though several reflex actions are performed by our nervous system, the familiar reflexes are the knee jerk, pupil constriction, pulling away from very hot or cold objects, breathing and stretching. Most reflex actions are carried out by the spinal cord and do not involve the brain.

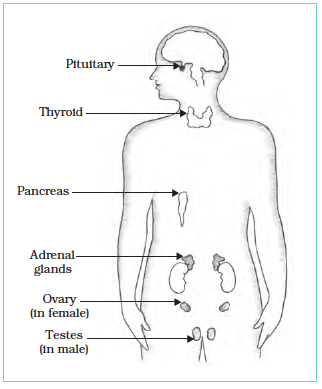

The Endocrine System

The endocrine glands play a crucial role in our development and behaviour. They secrete specific chemical substances, called hormones, which control some of our behaviours. These glands are called ductless glands or endocrine glands, because they do not have any duct (unlike other glands) to send their secretions to specific places. Hormones are circulated by the bloodstream. The endocrine glands form the endocrine system of the body. This system works in conjunction with different parts of the nervous system. The whole system is thus known as neuroendocrine system. Figure 3.6 shows the major endocrine glands of the body.

Fig.3.6 : Major Endocrine Glands

Pituitary Gland

This gland is situated within the cranium just below the hypothalamus. The pituitary gland is divided into anterior pituitary and posterior pituitary. The anterior pituitary is directly connected with hypothalamus, which regulates its hormonal secretions. The pituitary gland secretes the growth hormone and many other hormones, which direct and regulate the secretions of many other endocrine glands found in our body. This is why the pituitary gland is known as the “master gland”.

Some hormones are secreted at a steady rate throughout life, while others are secreted at an appropriate time in life. For example, the growth hormone is released steadily through childhood, with some spurt during adolescence, but gonadotropic hormones are secreted at the age of puberty, which stimulates the secretion of appropriate sex hormones among boys and girls. As a result, primary and secondary sexual changes take place.

Thyroid Gland

This gland is located in the neck. It produces thyroxin that influences the body’s metabolic rate. Optimum amount of thyroxin is secreted and regulated by an anterior pituitary hormone, the Thyroid Stimulating Hormone. (TSH). The steady secretion of this hormone maintains the production of energy, consumption of oxygen and elimination of wastes in body cells. On the other hand, underproduction of thyroxin leads to physical and psychological lethargy. If thyroid gland is removed in young animals, their growth is stunted and they fail to develop sexually.

Adrenal Gland

This gland is located above each kidney. It has two parts, adrenal cortex and adrenal medulla, each secreting different hormones. The secretion of adrenal cortex is controlled and regulated by Adrenocorticotrophic Hormone (ACTH) secreted by anterior pituitary gland. When the secretion of adrenal cortex goes down, anterior pituitary gets the message and increases the secretion of ACTH, which stimulates the adrenal cortex to secrete more hormones.

The adrenal cortex secretes a group of hormones, called corticoids, which are utilised by the body for a number of physiological purposes, e.g., regulation of minerals in the body, particularly sodium, potassium, and chlorides. Any disturbance in its function seriously affects the functions of the nervous system.

Adrenal medulla secretes two hormones, namely epinephrine and norepinephrine (also known as adrenaline and noradrenaline, respectively). Sympathetic activation, such as increased heart rate, oxygen consumption, metabolic rate, muscle tone, etc., take place through the secretion of these two hormones. Epinephrine and norepinephrine stimulate the hypothalamus, which prolongs emotions in an individual even when the stressor has been removed.

Pancreas

The pancreas, lying near the stomach, has a primary role in digestion of food, but it also secretes a hormone known as insulin. Insulin helps the liver to break down glucose for use by the body or for storage as glycogen by the liver. When insulin is not secreted in proper amount, people develop a disease, called diabetic mellitus or simply diabetes.

Gonads

Gonads refer to testes in males and ovaries in females. The hormones secreted by these glands control and regulate sexual behaviours and reproductive functions of males and females. Secretion of hormones of these glands is initiated, maintained and regulated by a hormone, called gonadotrophic hormone (GTH) secreted by the anterior pituitary. The secretion of GTH starts at the age of puberty (10 to 14 years in human beings) and stimulates gonads to secrete hormones, which in turn stimulates development of primary and secondary sexual characteristics.

The ovaries in females produce estrogens and progesterone. Estrogens guide the sexual development of the female body. Primary sexual characteristics related with reproduction, such as development of ovum or egg cell, appear on every 28 days or so in the ovary of a sexually mature female. Secondary sexual characteristics, such as breast development, rounded body contours, widened pelvis, etc., also depend on this hormone. Progesterone has no role in sexual development. Its function is related with preparation of uterus for the possible reception of fertilised ovum.

The hormonal system for reproductive behaviour is much simpler in the male because there is no cyclic pattern. Testes in males produce sperm continuously and secrete male sex hormones called androgens. The major androgen is testosterone. Testosterone prompts secondary sexual changes such as physical changes, growth of facial and body hairs, deepening of voice, and increase in sexually oriented behaviour. Increased aggression and other behaviours are also linked with testosterone production.

The normal functioning of all hormones is crucial to our behavioural well-being. Without a balanced secretion of hormones, the body would be unable to maintain the state of internal equilibrium. Without the increased secretion of hormones during the times of stress, we would not be able to react effectively to potential dangers in our environment. Finally, without the secretion of hormones at specific times in our lives, we would not be able to grow, mature and reproduce.

Heredity : Genes and Behaviour

We inherit characteristics from our parents in the form of genes. A child at birth possesses a unique combination of genes received from both parents. This inheritance provides a distinct biological blueprint and timetable for an individual’s development. The study of the inheritance of physical and psychological characteristics from ancestors is referred to as genetics. The child begins life as a single zygote cell (mother’s ovum fertilised by father’s sperm). Zygote is a tiny cell with a nucleus in its center containing chromosomes. These chromosomes with all genes are inherited from each parent in equal numbers.

Chromosomes

Chromosomes are the hereditary elements of the body. They are threadlike-paired structures in the nucleus of each cell. The number of chromosomes per nucleus is distinctive, and is constant for each living organism. The gametic cells (sperm and ovum) have 23 chromosomes but not in pairs. A new generation results from the fusion of a sperm cell and an egg cell.

At the time of conception, the organism inherits 46 chromosomes from parents, 23 from the mother and 23 from the father. Each of these chromosomes contains thousands of genes. However, the sperm cell (fathers’) differs from the egg cell (mother’s) in one important respect. The 23rd chromosome of the sperm cell can be either the capital X or Y type of the English alphabet. If the X type sperm fertilises the egg cell, the fertilised egg will have an XX 23rd chromosome pair, and the child will be a female. On the other hand, if a Y type sperm fertilises the egg, the 23rd chromosome pair will be XY, and the child will be a male.

Activity 3.2

Divide the class in two groups and have a debate on the topic “Psychologists should leave the study of neurons, synapses and the nervous system to biologists”. One group should speak in favour and the other group against the motion.

Chromosomes are composed mainly of a substance called Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA). Our genes are composed chiefly of DNA molecules. The two genes that control the development of each trait are situated at the same locus, one on each chromosome of a particular pair. The exception is the sex chromosomes, i.e. the pair of chromosomes that determines an individual’s sex.

Genes

Every chromosome stores thousands of genetic commands in the form of genes. These genes dictate much of the course of an organism’s development. They contain instructions for the production of specific proteins, which regulate the body’s physiological processes and the expression of phenotypic traits. The observable traits of an organism are called phenotype (e.g., body built, physical strength, intelligence, and other behavioural traits). The traits, which can be passed on to the offspring through genetic material are called its genotype. All biological and psychological characteristics that a modern man possesses are the result of genotype inheritance with phenotypical variations.

A given gene can exist in several different forms. Change of a gene from one form to another is called mutation. The type of mutation that occurs spontaneously in nature provides variation in genotypes and permits the evolution of new species. Mutation permits recombination of new genes with the genes already present. This new combination of genes structure is then put to test in the environment, which can select out those genotypes that turn out to be best fitted for the environment.

Cultural Basis : Socio-Cultural Shaping of Behaviour

After reading the biological basis of behaviour you may have developed an idea that many of our behaviours are influenced by hormones and many others occur as reflexive responses. However, hormones and reflexes do not explain all of our behaviour. The hormones play an important role in regulating human physiology, but they do not completely control human behaviour. Similarly stereotype (fixed pattern), which is the most distinguishing feature of a reflex, does not appear with most human responses.

We can draw examples from several domains of our life to argue that our behaviour is more complex than the behaviour of animals. A major reason for this complexity is that unlike animals, human beings have a culture to regulate their behaviour. Let us consider the basic need of hunger. We know that it has a biological basis, which is common among animals and human beings, but the way this need is gratified by human beings is extremely complex. For example, some people eat vegetarian food, while others eat non-vegetarian food. How have they become vegetarians and non-vegetarians? Some vegetarians take eggs; others do not. Why is that so? Try to think how people have come to behave so differently in terms of food intake. If you explore further you will also find variations in the manner in which food is eaten (e.g., directly with hand, or with the help of spoons, forks and knives).

Sexual behaviour can be taken as another example. We know that this behaviour involves hormones and reflexive reactions in animals and human beings alike. While among animals sexual behaviour is fairly simple and reflexive (all animals indulge in sexual behaviour almost in the same manner), it is so complex among human beings that it can hardly be described as reflexive. Partner preferences are a key feature of human sexual behaviour. The bases of these preferences widely differ within and across societies. Human sexual behaviour is also governed by many rules, standards, values, and laws. However, these rules and standards also remain in a continuous process of change.

These examples illustrate that biological factors alone cannot help us very much in understanding human behaviour. The nature of human beings is very different from those provided to us by biological scientists. Human nature has evolved through an interplay of biological and cultural forces. These forces have made us similar in many ways and different in others.

Box 3.1 Biological and Cultural Transmission

In relatively modern years, a discipline called sociobiology has emerged that deals with the interaction of biology and society. It explains human social behaviour in an evolutionary framework on the basis of “inclusive fitness”, which means that each organism is supposed to behave in a manner so as to maximise its reproductive success. Researchers, who have studied several social behaviours (e.g., courtship, mating, child rearing), underscore the continuity of development of biologically related creatures. They recognise that human behaviour cannot be attributed solely to biological predispositions. It is greatly affected by learning. Heidi Keller, a distinguished psychologist, recently argued that genetic endowment should not be misunderstood as expressing fixed, deterministic relationships between genes and behaviour. She has proposed the notion of “genetic preparedness”, which suggests that acquisition of particular behaviours via learning occurs in fairly efficient ways to facilitate our adaptations with the environment.

It is now believed that human evolution involves both genetic and cultural transmissions. These transmission processes are different in certain respects, but they have parallel features. Genetic transmission is a process that occurs in all organisms in a similar manner, but cultural transmission is a unique human process. It involves intergenerational learning (via teaching and imitation), which makes it distinct from biological transmission. In cultural transmission, individuals are influenced by people other than their biological parents, while in biological transmission only the parents can be the source of influence. Thus, only human beings have “cultural parents” (e.g., members of extended families, teachers, and other influential people). Cultural evolution is also not restricted to intergenerational influences. Ideas are transmitted within generations so much so that it is even possible for older people to model their behaviour after younger ones.

The two processes are also similar in important ways. Both proceed in interaction with the demands of environment. Both involve changes that either stay or get lost depending on how adaptive they are (i.e., how nicely they fit the environment in which they first occurred). Thus, at the human level, we find evidence for a “dual inheritance” theory. Biological inheritance takes place through genes, while cultural inheritance takes place through memes. The former takes place in a “top-down” manner (i.e. from parents to children), while the latter may also take place in a “bottom-up” manner (i.e. from children to parents). Dual inheritance theory also shows that although biological and cultural forces may involve different processes, they work as parallel forces, and interact with each other in offering explanation of an individual’s behaviour.

Concept of Culture

You have read that human behaviour can be understood only by viewing it in the socio-cultural context in which it occurs. Human behaviour is fundamentally social. It involves relationships with other people, reactions to their behaviour, and engagement with innumerable products made available to us by our predecessors. Although many other species are also social like us, human beings are cultural as well.

You may ask: what does it mean to be cultural? In order to answer this question, we will need to understand the meaning of culture. In the simplest terms, culture refers to “the man-made part of the environment”. It comprises diverse products of the behaviour of many people, including ourselves. These products can be material objects (e.g., tools, sculptures), ideas (e.g., categories, norms) or social institutions (e.g., family, school). We find them almost everywhere. They influence behaviour, although we may not always be aware of it.

Let us look at some examples. The room you might be in now is a cultural product. It is the result of someone’s architectural ideas and building skills. Your room may be rectangular, but there are many places where rooms are not rectangular (e.g., those of Eskimos). While reading this chapter you might be sitting on a chair that some people designed and built some time ago. Since sitting in a chair requires a particular posture, this invention is shaping your behaviour. There are societies without chairs. Just try to think how people in those societies would be sitting in order to do some reading.

Students sit on chairs in the “classrooms”, but chairs are not found in all schools. In schools in most villages there are no chairs for students. They sit on the ground, or on a piece of sack spread over it. That in some societies children gather in rooms facing a teacher is another kind of cultural product, called “schooling”. This institution may have material aspects, such as buildings, and ideational aspects, such as the notion that schooling should take place at a specific place and time, or the idea that individuals attending “schools” must be evaluated and given certificates on successful completion of schooling. This institution also provides with behavioural expectation for all those who participate in it . Both teachers and students have a series of roles to play and responsibilities to share. Individuals, families and communities have different views about schooling. Some believe that school education is a valuable thing. They have unshaken faith that school education can make people powerful and change their destiny. Others consider it neither valuable nor do they have faith in its strength as such. Some societies emphasise on equal education for boys and girls; others do not. Some groups widely participate in the process of schooling, others (e.g., some tribal groups) participate little or not at all. People with special needs often remain deprived of school education for a number of reasons. People’s views about communities, gender, caste groups and those with special needs and their educability also differ widely across societies.

As you look around you will find that much of our life as human beings involves interacting with various cultural products, and behaving in accord with them. This means that culture shapes our behaviour in a significant manner. However, it may also be noted at this point that just as culture shapes us, we also shape our culture. Several anthropologists have pointed out the mutual influences of culture and psyche on each other. They suggest that the relationship between individuals and their social surroundings is interactive, and in the course of these interactions, they constitute each other. This perspective emphasises that human beings are not passive recipients of cultural forces. Instead, they themselves create the context in which their behaviour is shaped.

Activity 3.3

Talk to students belonging to different States regarding their food, festivals, dress, customs, etc.

Prepare a list of the differences and similarities and discuss with your teacher.

What is Culture?

In spite of the fact that culture is always with us, much confusion exists in defining culture. It is more like the notion of “energy” in physics or “group” in sociology. Some believe that culture really exists out there, and it matters to individuals, while others believe that culture does not really exist, instead it is an idea created and shared by a group of people.

The innumerable definitions of culture commonly point to some of its essential features. One is that culture includes behavioural products of others who preceded us. It indicates both substantial and abstract particulars that have prior existence in one form or another. Thus, culture is already there as we begin life. It contains values that will be expressed and a language in which to express them. It contains a way of life that will be followed by most of us who grow up in that context. Such a conceptualisation of culture tends to place it outside the individual, but there are also treatments of culture that places it in the minds of individuals. In the latter case, culture is identified with a historically transmitted pattern of meanings embodied in symbols. Culture provides meaning by creating significant categories like social practices (e.g., marriage) and roles (e.g., bridegroom) as well as values, beliefs and premises. As Richard Shweder put it, to learn that “a mother’s sister’s husband is an uncle”, one must somehow receive the ‘frame’ of understanding from others.

Whether culture is taken as an existing reality, or as an abstraction, or both, it exerts many real influences on human behaviour. It allows us to categorise and explain many important differences in human behaviour that were previously attributed to biological differences. Social and cultural contexts within which human development takes place vary widely over time and place. For example, some twenty years ago children in India would not have known several products that are now part of a child’s world. Similarly an Adivasi living in a remote forest or hilly area would not have a “pizza” or “sandwich” as breakfast.

In the previous paragraphs, we have made frequent use of the terms culture and society. Often they are considered to carry similar meaning. Let us note at this point that they are not the same thing. A society is a group of people who occupy a particular territory and speak a common language not generally understood by neighbouring people. A society may or may not be a single nation, but every society has its own culture, and it is culture that shapes human behaviour from society to society. Culture is the label for all the different features that vary from society to society. It is these different features of society whose influences psychologists want to examine in their studies of human behaviour. Thus, a group of people, who manage their livelihood through hunting and gathering in forests, would present a life characterised by certain features that will not be found in a society that lives mainly on agricultural produce or wage earnings.

Cultural Transmission

We have seen earlier that as human beings we are both biological and socio-cultural creatures. As biological creatures, we have certain vital needs. Their fulfilment enhances our chances of surviving. In fulfilling these needs we use most of our acquired skills. We also have a highly developed capacity to benefit from experiences of our own and those of others. No other creature has learning capacity to the same extent as we have. No other creature has created an organised system of learning, called education, and none in this universe wants to learn as much as we do. As a result, we display many forms of behaviour that are uniquely human, and creations of what we call culture. The processes of enculturation and socialisation make us cultural beings.

Enculturation

Enculturation refers to all learning that takes place without direct, deliberate teaching. We learn certain ideas, concepts, and values simply because of their availability in our cultural context. For example, what is “vegetable” and what is “weed” or what is “cereal” and what is “non-cereal” is defined by what is already there, previously labelled as “vegetable” or “cereal” and agreed upon by people at large. Such concepts are transmitted, both directly and indirectly, and are learned very well because they are an integral part of the life of a cultural group, and are never questioned. All such examples of learning are called “enculturation”.

Thus, enculturation refers to all learning that occurs in human life because of its availability in our socio-cultural context. The key element of enculturation is learning by observation. Whenever we learn any content of our society by observation, enculturation is in evidence. These contents are culturally shaped by our preceding generations. In this sense, enculturation always refers to learning something that is already available. A major part of our behaviour is the product of enculturation. In Indian families, many complex activities, like cooking, are learned by observation. There is no prescribed curriculum and no textbook for such activities, and there is also no deliberate instruction for cooking.

Although the effects of enculturation are obvious, people are generally not aware of these effects. They are also generally not aware of what is not available in the society to be learned. This leads to an apparent paradox that people who are most thoroughly enculturated are often the least aware of their culture’s role in modeling them.

Socialisation

Socialisation is a process by which individuals acquire knowledge, skills and dispositions, which enable them to participate as effective members of groups and society. It is a process that continues over the entire life-span, and through which one learns and develops ways of effective functioning at any stage of development. Socialisation forms the basis of social and cultural transmission from one generation to the next. Its failure in any society may endanger the very existence of that society.

The concept of socialisation suggests that all human beings are capable of a far greater repertoire of behaviours than they ever exhibit. We begin life in a particular social context, and there we learn to make certain responses and not others. The most clear example is our linguistic behaviour. Although we can speak any language that exists in this world, we learn to speak only that language which people around us speak. Within this social context we also learn many other things (e.g., when to express emotions and when to suppress them).

The probability of our behaving in a particular way is greatly affected by people who relate to us. Any one who possesses power relative to us can socialise us. Such people are called “socialisation agents”. These agents include parents, teachers and other elders, who are more knowledgeable in the ways of their society. Under certain conditions, however, even our age peers can affect socialisation.

The process of socialisation is not always a smooth transition between the individual and the socialisation agent. It sometimes involves conflicts. In such situations not only are some responses punished, but some are also blocked by the behaviour of others in effective ways. At the same time, several responses need to be rewarded so that they acquire greater strength. Thus, reward and punishment serve as basic means for achieving the goals of socialisation. In this sense, all socialisation seems to involve efforts by others to control behaviour.

Socialisation although primarily consists of deliberate teaching for producing “acceptable” behaviour, the process is not unidirectional. Individuals are not only influenced by their social environment, but they also influence it. In societies that comprise many social groups, individuals may choose those to which they wish to belong. With increased migration, individuals are not only socialised once, but are often re-socialised differently in their life-span. This process is known as acculturation which we will discuss later in this chapter.

Due to the processes of enculturation and socialisation we find behavioural similarities within societies and behavioural differences across societies. Both processes involve learning from other people. In the case of socialisation, the learning involves deliberate teaching. In the case of enculturation, teaching is not necessary for learning to take place. Enculturation means engagement of people in their culture. Since most of the learning takes place with our engagement in our culture, socialisation can be easily subsumed under the process of enculturation.

A good deal of our learning involves both enculturation and socialisation. Language learning is a good example. While a lot of language learning takes place spontaneously, there is also certain amount of direct teaching of the language, such as in grammar courses in elementary schools. On the other hand, learning of language other than the mother tongue, such as learning of Hindi by a European child, or of French by a child in India, is completely a deliberate process.

Socialisation Agents

A number of people who relate to us possess power to socialise us. Such people are called “socialisation agents”. Parents and family members are the most significant socialisation agents. Legal responsibility of child care, too, lies with parents. Their task is to nurture children in such a manner that their natural potentials are maximised and negative behaviour tendencies are minimised or controlled. Since each child is also part of a larger community or society, several other influences (e.g., teachers, peer groups) also operate on her/his life. We will briefly discuss some of these influences.

Parents

Parents have most direct and significant impact on children’s development. Children respond in different ways to parents in different situations. Parents encourage certain behaviours by rewarding them verbally (e.g., praising) or in other tangible ways (e.g., buying chocolates or objects of child’s desire). They also discourage certain behaviours through non-approving behaviours. They also arrange to put children in a variety of situations that provide them with a variety of positive experiences, learning opportunities, and challenges. While interacting with children parents adopt different strategies, which are generally known as parenting styles. A distinction is made between authoritative, authoritarian and democratic or permissive parenting styles. Studies indicate that parents vary enormously in the treatment of children in terms of their degree of acceptance and degree of control. The conditions of life in which parents live (poverty, illness, job stress, nature of family) also influence the styles they adopt in socialising children. Grandparental proximity and network of social relationships play considerable role in child socialisation directly or through parental influences.

School

School is another important socialising agent. Since children spend a long time in schools, which provide them with a fairly organised set up for interaction with teachers and peers, school is today being viewed as a more important agent of child socialisation than parents and family. Children learn not only cognitive skills (e.g., reading, writing, doing mathematics) but also many social skills (e.g., ways of behaving with elders and age mates, accepting roles, fulfilling responsibilities). They also learn and internalise the norms and rules of society. Several other positive qualities, such as self-initiative, self-control, responsibility, and creativity are encouraged in schools. These qualities make children more self-reliant. If the transaction has been successful, the skills and knowledge children acquire in schools either through curriculum or interaction with teachers and peers also get transferred to other domains of their life. Many researchers believe that a good school can altogether transform a child’s personality. That is why we find that even poor parents want to send their children to good schools.

Peer Groups

One of the chief characteristics of the middle childhood stage is the extension of social network beyond home. Friendship acquires great significance in this respect. It provides children not only with a good opportunity to be in company of others, but also for organising various activities (e.g., play) collectively with the members of their own age. Qualities like sharing, trust, mutual understanding, role acceptance and fulfilment develop in interaction with peers. Children also learn to assert their own point of view and accept and adapt to those of others. Development of self-identity is greatly facilitated by the peer group. Since communication of children with peer group is direct, process of socialisation is generally smooth.

Media Influences

In recent years media has also acquired the property of a socialisation agent. Through television, newspapers, books and cinema the external world has made/is making its way into our home and our lives. While children learn about many things from these sources, adolescents and young adults often derive their models from them, particularly from television and cinema. The exposure to violence on television is a major issue of discussion, since studies indicate that observing violence on television enhances aggressive behaviour among children. There is a need to use this agent of socialisation in a better way in order to prevent children from developing undesirable behaviours.

Activity 3.4

Observe 4-5 families belonging to different cultural and socio-economic background for about half an hour in the morning and evening interacting with their children for five days.

Do you find any difference in parental interaction with their sons and daughters?

Note their distinct pattern of behaviour and discuss this with your teacher.

Acculturation

Acculturation refers to cultural and psychological changes resulting from contact with other cultures. Contact may be direct (e.g., when one moves and settles in a new culture) or indirect (e.g., through media or other means). It may be voluntary (e.g., when one goes abroad for higher studies, training, job, or trade) or involuntary (e.g., through colonial experience, invasion, political refuge). In both cases, people often need to learn (and also they do learn) something new to negotiate life with people of other cultural groups. For example, during the British rule in India many individuals and groups adopted several aspects of British lifestyle. They preferred to go to the English schools, take up salaried jobs, dress in English clothes, speak English language, and change their religion.

Acculturation can take place any time in one’s life. Whenever it occurs, it requires re-learning of norms, values, dispositions, and patterns of behaviour. Changes in these aspects require re-socialisation. Sometimes people find it easy to learn these new things, and if their learning has been successful, shifts in their behaviour easily take place in the direction of the group that brings in acculturation. In this situation transition to a new life is relatively smooth and free from problems. On the other hand, in many situations people experience difficulties in dealing with new demands of change. They find change difficult, and are thrown into a state of conflict. This situation is relatively painful as it leads to experience of stress and other behavioural difficulties by acculturating individuals and groups.

Psychologists have widely studied how people psychologically change during acculturation. For any acculturation to take place contact with another cultural group is essential. This often generates some sort of conflict. Since people cannot live in a state of conflict for a long time, they often resort to certain strategies to resolve their conflicts. For a long time it was felt that social or cultural change oriented towards modernity was unidirectional, which meant that all people confronting the problem of change would move from a traditional state to a state of modernity. However, studies carried out with immigrants to western countries and native or tribal people in different parts of the world have revealed that people have various options to deal with the problem of acculturative changes. Thus, the course of acculturative change is multidirectional.

Activity 3.5

Make an attempt to find out people who have lived for an extended period of time in different cultures. Interview and ask them to give some examples of cultural differences and similarities in attitudes, norms, and values.

Changes due to acculturation may be examined at subjective and objective levels. At the subjective level, changes are often reflected in people’s attitudes towards change. They are referred to as acculturation attitudes. At the objective level, changes are reflected in people’s day-to-day behaviours and activities. These are referred to as acculturation strategies. In order to understand acculturation, it is necessary to examine it at both levels. At the objective level of acculturation, one can look at a variety of changes that might be evident in people’s life. Language, dressing style, means of livelihood, housing and household goods, ornaments, furniture, means of entertainment, use of technology, travel experience, and exposure to movies, etc. can provide clear indications of change that individuals and groups might have accepted in their life. Based on these indicators, we can easily identify the degree to which acculturative change has entered into an individual’s or a group’s life. The only problem is that these indicators do not always indicate conscious acceptance of change by individuals or groups; they are held by people because they are easily available and economically affordable. Thus, in some cases, these indicators appear somewhat deceptive.

In order to place some confidence in conscious acceptance of change, we need to analyse them at the subjective level. John Berry is well-known for his studies on psychological acculturation. He argues that there are two important issues that all acculturating individuals and groups face in culture-contact situations. One relates to the degree to which there is a desire to maintain one’s culture and identity. Another relates to the degree to which there is a desire to engage in daily interactions with members of other cultural group(s).

Based on people’s positive or negative answer to these issues, the following four acculturative strategies have been derived:

Integration : It refers to an attitude in which there is an interest in both, maintaining one’s original culture and identity, while staying in daily interaction with other cultural groups. In this case, there is some degree of cultural integrity maintained while interacting with other cultural groups.

Assimilation : It refers to an attitude, which people do not wish to maintain their cultural identity, and they move to become an integral part of the other culture. In this case, there is loss of one’s culture and identity.

Separation : It refers to an attitude in which people seem to place a value on holding on to their original culture, and wish to avoid interaction with other cultural groups. In this case, people often tend to glorify their cultural identity.

Marginalisation : It refers to an attitude in which there is little possibility or interest in one’s cultural maintenance, and little interest in having relations with other cultural groups. In this case, people generally remain undecided about what they should do, and continue to stay with a great deal of stress.

You have read in this chapter that human behaviour is not fully under the control of biological factors alone. Socio-cultural factors interact with biological dispositions of individuals to give a particular shape to their behaviour in a given society. Since societies and cultures across the globe are not homogeneous, human behaviour is also not expressed in the same way everywhere. This allows us to say that besides biological roots, there are cultural roots of human behaviour. While genes write the script of biological transmissions, memes write the script of cultural transmissions. The genes and memes work together to allow behaviour to unfold partly in some similar and partly in different ways within and across societies. Understanding of cultural basis of behaviour will make you realise that behavioural differences between individuals or groups are not due to the structural and functional properties of their biological system alone. Cultural features of individuals and groups contribute in significant ways in generating behavioural differences.

KeyTerms

Acculturation, All-Or-None Property/Principle, Arousal, Axons, Brain stem, Central nervous system, Cerebellum, Cerebral cortex, Chromosomes, Cortex, Culture, Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA), Enculturation, Endocrine glands, Environment, Evolution, Genes, Hemispheres, Heredity, Homo sapiens, Homeostasis, Hypothalamus, Medulla, Memes, Nerve impulse, Neurons, Nucleus, Reticular Activating System (RAS), Skeletal muscles, Socialisation, Soma (Cell body), Somatic nervous system, Species, Synaptic vesicles

Summary

• The human nervous system consists of billions of interconnected, highly specialised cells called neurons. Neurons or nerve cells control and coordinate all human behaviour.

• The central nervous system (CNS) consists of the brain and spinal cord. Peripheral nervous system branches out from the CNS to all parts of the body. It has two divisions: the somatic nervous system (related to the control of skeletal muscles) and the autonomic nervous system (related to control of internal organs). The autonomic system is sub-divided into the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems.

• Neurons have dendrites, which receive impulses; and the axon, which transmits impulses from cell body to other neurons or to muscle tissue.

• Every axon is separated by a gap called synapse. A chemical called neurotransmitter is released from the axon terminal that carries the message to the other neuron.

• The central core of the human brain includes hindbrain (consisting of the medulla, the pons, the reticular formation, and the cerebellum), the midbrain, and the thalamus and hypothalamus. Above the central core lies the forebrain or cerebral hemispheres.

• The limbic system is involved in the regulation of behaviours such as fighting, fleeing etc. It is comprised of hippocampus, amygdala and hypothalamus.

• The endocrine system consists of the glands; pituitary gland, thyroid gland, adrenal gland, pancreas and gonads. The hormones secreted by them play a crucial role in behaviour and development.

• In addition to biological factors, culture is considered an important determinant of human behaviour. If refers to the man-made part of the environment, which has two aspects —material and subjective. It refers to a shared way of life of a group of people through which they derive meanings of their behaviours and base their practices. These meanings and practices are transmitted through generations.

• Though, biological factors play a general enabling role, the development of specific skills and competencies is dependent upon the cultural factors and processes.

• We learn about culture through the processes of enculturation and socialisation. Enculturation refers to all learning that take place without direct, deliberate teaching.

• Socialisation is a process by which individuals acquire knowledge, skills and dispositions, which enable them to participate as effective members of groups and society. The most significant socialisation agents are parents, school, peer groups, mass media, etc.

• Acculturation refers to cultural and psychological changes resulting from contact with other cultures. The acculturative strategies adopted by individuals during the course of acculturation are integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalisation.

Review Questions

1. How does the evolutionary perspective explain the biological basis of behaviour?

2. Describe how neurons transmit information?

3. Name the four lobes of the cerebral cortex. What functions do they perform?

4. Name the various endocrine glands and the hormones secreted by them. How does the endocrine system affect our behaviour?

5. How does the autonomic nervous system help us in dealing with an emergency situation?

6. Explain the meaning of culture and describe its important features.

7. Do you agree with the statement that ‘biology plays an enabling role, while specific aspects of behaviour are related to cultural factors’? Give reasons in support of your answer.

8. Describe the main agents of socialisation.

9. How can we distinguish between enculturation and socialisation? Explain.

10. What is meant by acculturation? Is acculturation a smooth process? Discuss.

11. Discuss the acculturative strategies adopted by individuals during the course of acculturation.

Project Ideas

1. Collect information on a person with brain damage. You can take help from a doctor, consult books or search the internet. Compare it with the normal functioning brain and prepare a report.

2. Write down your daily routine. This should include the activity undertaken, as well as the time when it is done. For example, if you watch television between 7 p.m. and 8 p.m. daily, you should write down the time as well as the activity. Put in as many details as you can. You could include names of the specific programmes you watch on Television. Make a separate schedule for weekdays and weekends. The class can examine the daily schedules, and see which activities are more common amongst the students. Can some cultural values/beliefs be inferred to underlie common, shared experiences? (for example, that all students spend many hours in school on a daily basis reflects that they come from cultures which value school education).