Table of Contents

Motivation and Emotion

After reading this chapter, you would be able to

• understand the nature of human motivation,

• describe the nature of some important motives,

• describe the nature of emotional expression,

• understand the relationship between culture and emotion, and

• know how to manage your own emotions.

Emotion has taught mankind to reason.

– Marquis de Vauvenargues

Contents

Introduction

Nature of Motivation

Types of Motives

Biological Motives

Psychosocial Motives

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Self-Motivation (Box 9.1)

Nature of Emotions

Physiological Bases of Emotions

Physiology of Emotion (Box 9.2)

Lie Detection (Box 9.3)

Cognitive Bases of Emotions

Cultural Bases of Emotions

Expression of Emotions

Culture and Emotional Expression

Culture and Emotional Labeling

Managing Negative Emotions

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (Box 9.4)

Management of Examination Anxiety (Box 9.5)

Enhancing Positive Emotions

Emotional Intelligence (Box 9.6)

Key Terms

Summary

Project Ideas

Review Questions

Introduction

Sunita, a girl from a little known town, puts in 10-12 hours of hard work everyday in order to get through the various engineering entrance examinations. Hemant, a physically challenged boy, wants to take part in an expedition and trains himself extensively in a mountaineering institute. Aman saves money from his scholarship so that he can buy a gift for his mother. These are just a few examples, which indicate the role motivation plays in human behaviour. Each of these behaviours are caused by an underlying motive. Behaviour is goal-driven. Goal-seeking behaviour tends to persist until the goal is achieved. For achieving their goals people plan and undertake different activities. How is Sunita going to feel if after all the hard work she has put in, she does not succeed or Aman’s scholarship money gets stolen. Sunita, perhaps, will be sad and Aman angry. This chapter will help you to understand the basic concepts of motivation and emotion, and related developments in these two areas. You will also get to know the concepts of frustration and conflict. The basic emotions, their biological bases, overt expressions, cultural influences, their relationship with motivation, and some techniques to help you manage your emotions better will also be dealt with.

Nature of Motivation

The concept of motivation focuses on explaining what “moves” behaviour. In fact, the term motivation is derived from the Latin word ‘movere’, referring to movement of activity. Most of our everyday explanation of behaviour is given in terms of motives. Why do you come to the school or college? There may be any number of reasons for this behaviour, such as you want to learn or to make friends, you need a diploma or degree to get a good job, you want to make your parents happy, and so on. Some combination of these reasons and/or others would explain why you choose to go in for higher education. Motives also help in making predictions about behaviour. A person will work hard in school, in sports, in business, in music, and in many other situations, if s/he has a very strong need for achievement. Hence, motives are the general states that enable us to make predictions about behaviour in many different situations. In other words, motivation is one of the determinants of behaviour. Instincts, drives, needs, goals, and incentives come under the broad cluster of motivation.

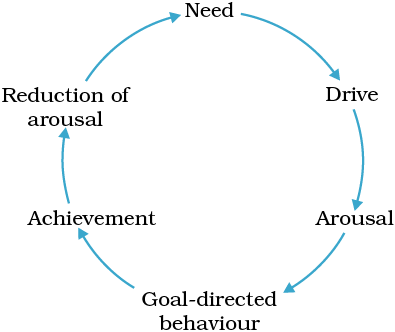

The Motivational Cycle

Psychologists now use the concept of need to describe the motivational properties of behaviour. A need is lack or deficit of some necessity. The condition of need leads to drive. A drive is a state of tension or arousal produced by a need. It energises random activity. When one of the random activities leads to a goal, it reduces the drive, and the organism stops being active. The organism returns to a balanced state. Thus, the cycle of motivational events can be presented as shown in Fig.9.1.

Fig.9.1 : The Motivational Cycle

Are there different types of motives? Are there any biological bases explaining different kinds of motives? What happens if your motive remains unfulfilled? These are some of the questions we will discuss in the following sections.

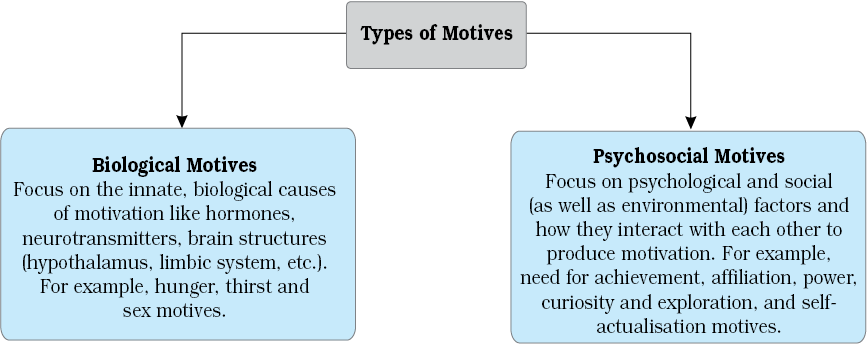

Types of Motives

Basically, there are two types of motives : biological and psychosocial. Biological motives are also known as physiological motives as they are guided mostly by the physiological mechanisms of the body. Psychosocial motives, on the other hand, are primarily learned from the individual’s interactions with the various environmental factors.

However, both types of motives are interdependent on each other. That is, in some kind of situations the biological factors may trigger a motive whereas in some other situations, the psychosocial factors may trigger the motive. Hence, you should keep in mind that no motive is absolutely biological or psychosocial per se, rather they are aroused in the individual with varying combinations.

Biological Motives

The biological or physiological approach to explain motivation is the earliest attempt to understand causes of behaviour. Most of the theories, which developed later, carry traces of the influence of the biological approach. The approach adhering to the concept of adaptive act holds that organisms have needs (internal physiological imbalances) that produce drive, which stimulates behaviour leading to certain actions towards achieving certain goals, which reduce the drive. The earliest explanations of motivation relied on the concept of instinct. The term instinct denotes inborn patterns of behaviour that are biologically determined rather than learned. Some common human instincts include curiosity, flight, repulsion, reproduction, parental care, etc. Instincts are innate tendencies found in all members of a species that direct behaviour in predictable ways. The term instinct most approximately refers to an urge to do something. Instinct has an “impetus” which drives the organism to do something to reduce that impetus. Some of the basic biological needs explained by this approach are hunger, thirst, and sex, which are essential for the sustenance of the individual.

Fig.9.2 : Types of Motives

Hunger

When someone is hungry, the need for food dominates everything else. It motivates people to obtain and consume food. Of course we must eat to live. But, what makes you feel hungry? Studies have indicated that many events inside and outside the body may trigger hunger or inhibit it. The stimuli for hunger include stomach contractions, which signify that the stomach is empty, a low concentration of glucose in the blood, a low level of protein and the amount of fats stored in the body. The liver also responds to the lack of bodily fuel by sending nerve impulses to the brain. The aroma, taste or appearance of food may also result in a desire to eat. It may be noted that none of these alone gives you the feeling that you are hungry. All in combination act with external factors (such as taste, colour, by observing others eating, and the smell of food, etc.) to help you understand that you are hungry. Thus, it can be said that our food intake is regulated by a complex feeding-satiety system located in the hypothalamus, liver, and other parts of the body as well as the external cues available in the environment.

Some physiologists hold that changes in the metabolic functions of the liver result in a feeling of hunger. The liver sends a signal to a part of the brain called hypothalamus. The two regions of hypothalamus involved in hunger are - the lateral hypothalamus (LH) and the ventro-medial hypothalamus (VMH). LH is considered to be the excitatory area. Animals eat when this area is stimulated. When it is damaged, animals stop eating and die of starvation. The VMH is located in the middle of the hypothalamus, which is otherwise known as hunger-controlling area which inhibits the hunger drive. Now can you guess about people who overeat and become obese, and people who eat very little or who are on a diet?

Thirst

What would happen to you, if you were deprived of water for a long time? What makes you feel thirsty? When we are deprived of water for a period of several hours, the mouth and throat become dry, which leads to dehydration of body tissues. Drinking water is necessary to wet a dry mouth. But a dry mouth does not always result in water drinking behaviour. In fact processes within the body itself control thirst and drinking of water. Water must get into the tissues sufficiently to remove the dryness of mouth and throat.

Motivation to drink water is mainly triggered by the conditions of the body: loss of water from cells and reduction of blood volume. When water is lost by bodily fluids, water leaves the interior of the cells. The anterior hypothalamus contains nerve cells called ‘osmoreceptors’, which generate nerve impulses in case of cell dehydration. These nerve impulses act as a signal for thirst and drinking; when thirst is regulated by loss of water from the osmoreceptors, it is called cellular-dehydration thirst. But what mechanisms stop the drinking of water? Some researchers assume that the mechanism which explains the intake of water is also responsible for stopping the intake of water. Others have pointed out that the role of stimuli resulting from the intake of water in the stomach must have something to do with stopping of drinking water. However, the precise physiological mechanisms underlying the thirst drive are yet to be understood.

Sex

One of the most powerful drives in both animals and human beings is the sex drive. Motivation to engage in sexual activity is a very strong factor influencing human behaviour. However, sex is far more than a biological motive. It is different from other primary motives (hunger, thirst) in many ways like, (a) sexual activity is not necessary for an individual’s survival; (b) homeostasis (the tendency of the organism as a whole to maintain constancy or to attempt to restore equilibrium if constancy is disturbed) is not the goal of sexual activity; and (c) sex drive develops with age, etc. In case of lower animals, it depends on many physiological conditions; in case of human beings, the sex drive is very closely regulated biologically, sometimes it is very difficult to classify sex purely as a biological drive.

Physiologists suggest that intensity of the sexual urge is dependent upon chemical substances circulating in the blood, known as sex hormones. Studies on animals as well as human beings have mentioned that sex hormones secreted by gonads, i.e. testes in males and the ovaries in females are responsible for sexual motivation. Sexual motivation is also influenced by other endocrine glands, such as adrenal and pituitary glands. Sexual drive in human beings is primarily stimulated by external stimuli and its expression depends upon cultural learning.

Psychosocial Motives

Social motives are mostly learned or acquired. Social groups such as family, neighbourhood, friends, and relatives do contribute a lot in acquiring social motives. These are complex forms of motives mainly resulting from the individual’s interaction with her/his social environment.

Need for Affiliation

Most of us need company or friend or want to maintain some form of relationship with others. Nobody likes to remain alone all the time. As soon as people see some kinds of similarities among themselves or they like each other, they form a group. Formation of group or collectivity is an important feature of human life. Often people try desperately to get close to other people, to seek their help, and to become members of their group. Seeking other human beings and wanting to be close to them both physically and psychologically is called affiliation. It involves motivation for social contact. Need for affiliation is aroused when individuals feel threatened or helpless and also when they are happy. People high on this need are motivated to seek the company of others and to maintain friendly relationships with other people.

Need for Power

Need for power is an ability of a person to produce intended effects on the behaviour and emotions of another person. The various goals of power motivation are to influence, control, persuade, lead, and charm others and most importantly to enhance one’s own reputation in the eyes of other people.

David McClelland (1975) described four general ways of expression of the power motive. First, people do things to gain feeling of power and strength from sources outside themselves by reading stories about sports stars or attaching themselves to a popular figure. Second, power can also be felt from sources within us and may be expressed by building up the body and mastering urges and impulses. Third, people do things as individuals to have an impact on others. For example, a person argues, or competes with another individual in order to have an impact or influence on that person. Fourth, people do things as members of organisations to have an impact on others as in the case of the leader of a political party; the individual may use the party apparatus to influence others. However, for any individual, one of these ways of expressing power motivation may dominate, but with age and life experiences, it varies.

Need for Achievement

You might have observed some students work very hard and compete with others for good marks/grades in the examination, as good marks/grades will create opportunities for higher studies and better job prospects. It is the achievement motivation, which refers to the desire of a person to meet standards of excellence. Need for achievement, also known as n-Ach, energises and directs behaviour as well as influences the perception of situations.

During the formative years of social development, children acquire achievement motivation. The sources from which they learn it, include parents, other role models, and socio-cultural influences. Persons high in achievement motivation tend to prefer tasks that are moderately difficult and challenging. They have stronger-than-average desire for feedback on their performance, that is to know how they are doing, so that they can adjust their goals to meet the challenge.

Curiosity and Exploration

Often people engage in activities without a clear goal or purpose but they derive some kind of pleasure out of it. It is a motivational tendency to act without any specific identifiable goal. The tendency to seek for a novel experience, gain pleasure by obtaining information, etc. are signs of curiosity. Hence, curiosity describes behaviour whose primary motive appears to remain in the activities themselves.

What will happen if the sky falls on us? Questions of this kind (What will happen if…) stimulate intellectuals to find answers. Studies show that this curiosity behaviour is not only limited to human beings, animals too show the same kind of behaviour. We are driven to explore the environment by our curiosity and our need for sensory stimulation. The need for varied types of sensory stimulations is closely related to curiosity. It is the basic motive, and exploration and curiosity are the expressions of it.

Our ignorance about a number of things around us becomes a powerful motivator to explore the world. We get easily bored with repetitive experiences. So we look for something new.

In the case of infants and small children, this motive is very dominant. They get satisfaction from being allowed to explore, which is reflected in their smiling and babbling. Children become easily distressed, when the motive to explore is discouraged, as you have read in Chapter 4.

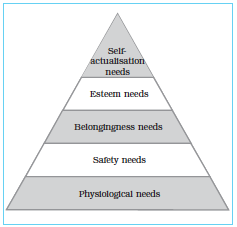

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

There are various views on human motivation, the most popular among these is given by Abraham H. Maslow (1968; 1970). He attempted to portray a picture of human behaviour by arranging the various needs in a hierarchy. His viewpoint about motivation is very popular because of its theoretical and applied value which is popularly known as the “Theory of Self-actualisation” (see Fig.9.3).

Fig.9.3 : Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s model can be conceptualised as a pyramid in which the bottom of this hierarchy represents basic physiological or biological needs which are basic to survival such as hunger, thirst, etc. Only when these needs are met, the need to be free from threatened danger arises. This refers to the safety needs of physical and psychological nature. Next comes the need to seek out other people, to love and to be loved. After these needs are fulfilled, the individual strives for esteem, i.e. the need to develop a sense of self-worth. The next higher need in the hierarchy reflects an individual’s motive towards the fullest development of potential, i.e. self-actualisation. A self-actualised person is self-aware, socially responsive, creative, spontaneous, open to novelty, and challenge. S/he also has a sense of humour and capacity for deep interpersonal relationships.

Lower level needs (physiological) in the hierarchy dominate as long as they are unsatisfied. Once they are adequately satisfied, the higher needs occupy the individual’s attention and effort. However, it must be noted that very few people reach the highest level because most people are concerned more with the lower level needs.

Activity 9.1

Actual actions sometimes contradict the hierarchy of needs. Soldiers, police officers, and fire personnels have been known to protect others by facing very endangering situations, seemingly in direct contradiction to the prominence of safety needs.

Why does it happen? Discuss it in your group and then with your teacher.

Frustration and Conflict

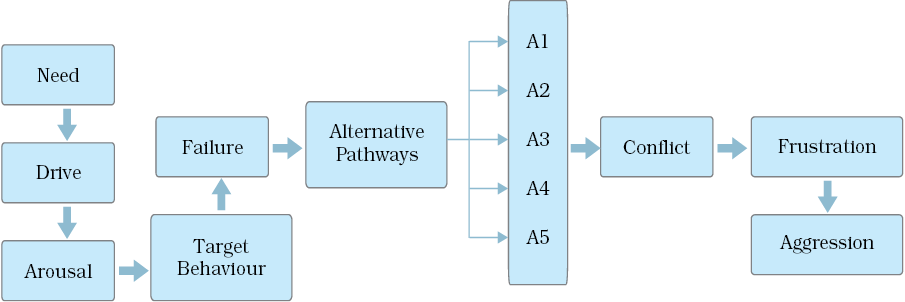

Frustration

We come across many occasions when things go in an unexpected direction and we fail to realise our goal. The blocking of a desired goal is painful, but all of us experience it in life in different degrees. Frustration occurs when an anticipated desirable goal is not attained and the motive is blocked. It is an aversive state and no one likes it. Frustration results in a variety of behavioural and emotional reactions. They include aggressive behaviour, fixation, escape, avoidance, and crying. In fact frustration-aggression is a very famous hypothesis proposed by Dollard and Miller. It states that frustration produces aggression. Aggressive acts are often directed towards the self or blocking agent, or a substitute. Direct aggressive acts may be inhibited by the threat of punishment. The main sources or causes of frustration are found in: (i) environmental forces, which could be physical objects, constraining situations or even other people who prevent a person from reaching a particular goal, (ii) personal factors like inadequacies or lack of resources that make it difficult or impossible to reach goals, and (iii) conflicts between different motives.

Fig.9.4 : Need-Conflict-Frustration Route

Conflict

Conflict occurs whenever a person must choose between contradictory needs, desires, motives, or demands. There are three basic forms of conflicts, for example, approach-approach conflict, avoidance-avoidance conflict, and approach-avoidance conflict.

Approach-approach conflict comes from having to choose between two positives and desirable alternatives. Avoidance-avoidance conflict comes from choosing between two negatives, or mutually undesirable alternatives. In real life, these double avoidance conflicts involve dilemmas such as choosing between the dentist and tooth decay, roadside food and starvation, etc. Approach-avoidance conflict comes from being attracted to and repelled by the same goal or activity. These types of conflicts are also difficult to resolve, as they are more troublesome than avoidance conflicts. A central characteristic of approach-avoidance conflict is ambivalence — a mix of positive and negative conflicts. Some examples of approach-avoidance conflicts are: a person wanting to buy a new motorbike but not wanting to make monthly payments, wanting to eat when one is overweight, and planning to marry someone her/his parents strongly disapprove of. Many of life’s important decisions have approach-avoidance dimensions.

Box 9.1 Self-Motivation

Here are a few ways of motivating your own self as well as others:

1. Be planned and organised in whatever you do.

2. Learn to prioritise your goals (Rank them 1,2, 3…).

3. Set short-term targets (In a few days, a week, a month, and so on).

4. Reward yourself for hitting the set targets (You could reward yourself with small things like a new pen, chocolates or anything that you want to have but attach it with some small goal).

5. Compliment yourself on being an achiever each time you hit a target (Say “Cheers! I did it”, “I am really good with that”, “I think I can do things smartly”, etc.).

6. If the targets seem difficult to attain, again break them up into smaller ones and approach them one by one.

7. Always try to visualise or imagine the outcomes of all the hard work you have to put in to reach your set goals.

A major source of frustration lies in motivational conflict. In life, we are often influenced by a number of competing forces that propel us in different directions. Such situations demonstrate the condition of conflict. Hence, the simultaneous existence of multiple wishes and needs characterise conflict.

In all the cases of conflicts, the selection of one option against the other depends on the relative strength/importance of one over the other, and environmental factors. Conflicting situations should be resolved after due consideration of the pros and cons of each of the choices. A point to note here is that conflicts cause frustration, which in turn, can lead to aggression. For instance, a young man who wants to be a musician but is pursuing a course in management due to parental pressure and is not able to perform as per the expectations of his parents may turn aggressive upon being questioned on his poor performance in the course.

Activity 9.2

Try to answer the following questions and work on the weaker areas:

1. List the plans/activities you intend to undertake during this week.

2. Do you have any goals set for the month ahead? If yes, what are they? Try to list them.

3. Do you have a daily routine chart? If not, then try to prepare one by distributing your time judiciously for studies, rest, recreation, and other activities, if any.

4. Are you able to follow your routine chart successfully? (If you already have one).

5. If you are not able to follow a routine successfully think about the ways in which you could overcome your irregular habits and try to follow them.

Nature of Emotions

Joy, sorrow, hope, love, excitement, anger, hate, and many such feelings are experienced in the course of the day by all of us. The term emotion is often considered synonymous with the terms ‘feeling’ and ‘mood’. Feeling denotes the pleasure or pain dimension of emotion, which usually involves bodily functions. Mood is an affective state of long duration but of lesser intensity than emotion. Both these terms are narrower than the concept of emotion. Emotions are a complex pattern of arousal, subjective feeling, and cognitive interpretation. Emotions, as we experience them, move us internally, and this process involves physiological as well as psychological reactions.

Emotion is a subjective feeling and the experience of emotions varies from person to person. In psychology, attempts have been made to identify basic emotions. It has been noted that at least six emotions are experienced and recognised everywhere. These are: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. Izard has proposed a set of ten basic emotions, i.e. joy, surprise, anger, disgust, contempt, fear, shame, guilt, interest, and excitement with combinations of them resulting in other emotional blends. According to Plutchik, there are eight basic or primary emotions. All other emotions result from various mixtures of these basic emotions. He arranged these emotions in four pairs of opposites, i.e. joy-sadness, acceptance-disgust, fear-anger, and surprise-anticipation.

Emotions vary in their intensity (high, low) and quality (happiness, sadness, fear). Subjective factors and situational contexts influence the experience of emotions. These factors are gender, personality, and psychopathology of certain kinds. Evidence indicates that women experience all the emotions except anger more intensely than men. Men are prone to experience high intensity and frequency of anger. This gender difference has been attributed to the social roles attached to men (competitiveness) and women (affiliation and caring).

Physiological Bases of Emotions

‘Divya is desperate to get a job. She has prepared well for the interview and feels confident. As she enters the room and the interview begins, she becomes extremely tense. Her feet go cold, her heart starts pounding, and she is unable to answer appropriately’.

Why did this happen? Try thinking about a similar situation that you have faced sometime in your life. Can you describe probable reasons for this? As we will see, a great deal of physiological changes happen when we experience emotion. When we are excited, afraid or angry, these bodily changes might be relatively easy to note. All of you must have noted the increase in heart rate, throbbing temples, increased perspiration, and trembling in your limbs when you are angry or excited about something. Sophisticated equipment has made it possible to measure the exact physiological changes that accompany emotions. Both autonomic as well as somatic nervous system play important roles in the emotional process. The experience of emotions is a result of a series of neurophysiological activations in which thalamus, hypothalamus, limbic system, and the cerebral cortex are involved significantly. Individuals with extensive injury in these brain areas have been known to demonstrate impaired emotional abilities. Selective activation of different brain areas has been experimentally shown to arouse different emotions in infants and adults.

Box 9.2 Physiology of Emotion

The nervous system, central as well as peripheral, plays a vital role in the regulation of emotion.

Thalamus : It is composed of a group of nerve cells and acts as a relay center of sensory nerves. Stimulation of thalamus produces fear, anxiety, and autonomic reactions. A theory of emotion given by Cannon and Bard (1931) emphasises the role of thalamus in mediating and initiating all emotional experiences.

Hypothalamus : It is considered the primary center for regulation of emotion. It also regulates the homeostatic balance, controls autonomic activity and secretion of endocrine glands, and organises the somatic pattern of emotional behaviour.

Limbic System : Along with thalamus and hypothalamus the limbic system plays a vital role in regulation of emotion. Amygdala is a part of limbic system, responsible for emotional control and involves formation of emotional memories.

Cortex : Cortex is intimately involved in emotions. However, its hemispheres have a contrasting role to play. The left frontal cortex is associated with positive feelings whereas the right frontal cortex with negative feelings.

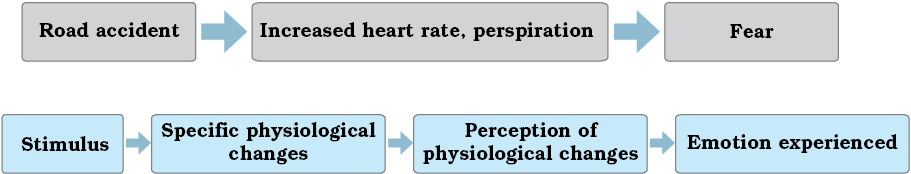

One of the earliest physiological theories of emotion was given by James (1884) and supported by Lange, hence, it has been named the James-Lange theory of emotion (see Fig.9.5). The theory suggests that environmental stimuli elicit physiological responses from viscera (the internal organs like heart and lungs), which in turn, are associated with muscle movement. For example, startling at an unexpected intense noise triggers activation in visceral and muscular organs followed by an emotional arousal. Put in other words, James-Lange theory argues that your perception about your bodily changes, like rapid breathing, a pounding heart, and running legs, following an event, brings forth emotional arousal. The main implication made by this theory is that particular events or stimuli provoke particular physiological changes and the individual’s perception of these changes results in the emotion being experienced.

Fig.9.5 : James-Lange Theory of Emotion

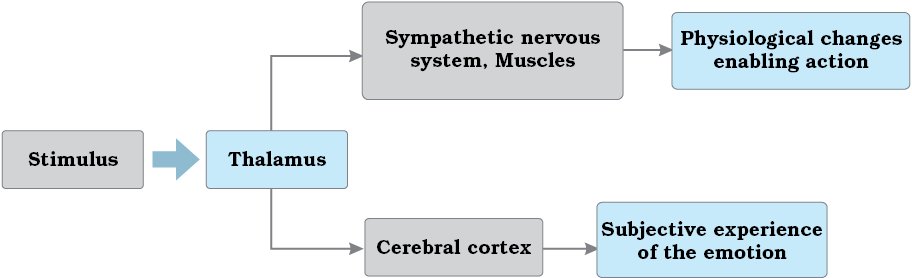

However,this theory faced a lot of criticism and fell in disuse. Another theory was proposed by Cannon(1927) and Bard (1934). The Cannon-Bard theory claims that the entire process of emotion is mediated by thalamus which after perception of the emotion-provoking stimulus, conveys this information simultaneously to the cerebral cortex and to the skeletal muscles and sympathetic nervous system. The cerebral cortex then determines the nature of the perceived stimulus by referring to past experiences. This determines the subjective experience of the emotion. At the same time the sympathetic nervous system and the muscles provide physiological arousal and prepare the individual to take action (see Fig.9.6).

Fig.9.6 : Cannon-Bard Theory of Emotion

The ANS is divided into two systems, sympathetic and parasympathetic. These two systems function together in a reciprocal manner. In a stressful situation the sympathetic system prepares the body to face the situation. It strengthens the internal environment of the individual by controlling the fall in heart rate, blood pressure, blood sugar, etc. It induces a state of physiological arousal that prepares the individual for fight or flight response in order to face the stressful situation. As the threat is removed the parasympathetic system gets active and restores the balance by calming the body. It restores and conserves energy and brings the individual back to a normal state.

Fig.9.7 : Schachter-Singer Theory of Emotion

Though acting in an antagonistic manner, the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are complementary to each other in completing the process of experience and expression of emotion.

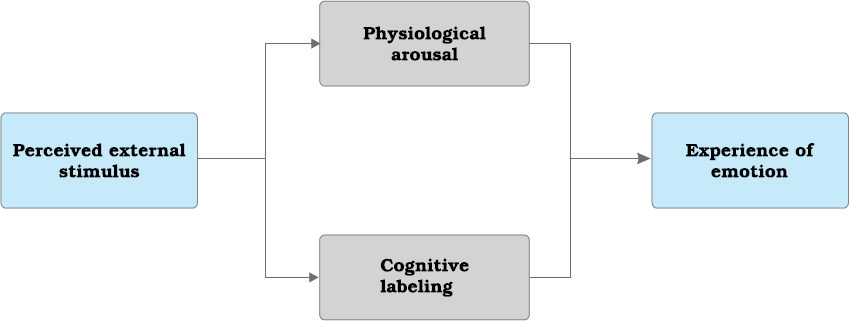

Cognitive Bases of Emotions

Most psychologists today believe that our cognitions, i.e. our perceptions, memories, interpretations are essential ingredients of emotions. Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer have proposed a two-factor theory in which emotions have two ingredients: physical arousal and a cognitive label. They presumed that our experience of emotion grows from our awareness of our present arousal. They also believed that emotions are physiologically similar. For example, your heart beats faster when you are excited or scared or angry. You are physiologically aroused and look to the external world for explanation. Thus, in their view an emotional experience requires a conscious interpretation of the arousal.

Box 9.3 Lie Detection

Lie detectors are also called polygraphs because they graphically record several bodily reactions simultaneously which measure the bodily arousal of the individual. Typically a lie detector measures changes in blood pressure, heart rate, breathing rate and depth, and the Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) which indicates variations in the electrical conductivity of the skin.

The individual being tested is first asked a series of neutral (control) questions to establish the baseline. Simple questions are followed by specific questions that are designed to evoke responses from a guilty knowledge supposedly indicating the individual’s involvement in the crime being investigated. The lie detector or the polygraph records the changes in neurophysiological activities that occur while the suspected individual answers these questions.

Though the polygraph makes several objective recordings, the interpretation of these records relies heavily on the subjective judgment by the examiner. It is also probable that several unrelated factors like fear, pain or anxiety being felt by the individual during the test may affect her/his level of arousal. It is possible for the individual to lie with it. The validity of polygraph results is doubtful; however these are still used by law-enforcing agencies for lie detection.

If you are aroused after physical exercise and someone teases you, the arousal already caused by the exercise may lead to provocation. To test this theory, Schachter and Singer (1962) injected subjects with epinephrine, a drug that produces high arousal. Then these subjects were made to observe the behaviour of others, either in an euphoric manner (i.e. shooting papers at a waste basket) or in an angry manner (i.e. stomping out of the room). As predicted, the euphoric and angry behaviour of others influenced the cognitive interpretation of the subjects’ own arousal.

Cultural Bases of Emotions

Till now we have been discussing the physiological and the cognitive bases of emotions. This section will examine the role of culture in emotions. Studies have revealed that the most basic emotions are inborn and do not have to be learned. Psychologists largely have a notion that emotions, especially facial expressions, have strong biological ties. For example, children who are visually impaired from birth and have never observed the smile or seen another person’s face, still smile or frown in the same way that children with normal vision do.

But on comparing different cultures we see that learning plays an important role in emotions. This happens in two ways. First, cultural learning influences the expression of emotions more than what is experienced, for example, some cultures encourage free emotional expression, whereas other cultures teach people, through modeling and reinforcement, to reveal little of their emotions in public.

Second, learning has a great deal to do with the stimuli that produce emotional reactions. It has been shown that individuals with excessive fears (phobia) of elevators, automobiles, and the like learnt these fears through modeling, classical conditioning or avoidance conditioning.

Expression of Emotions

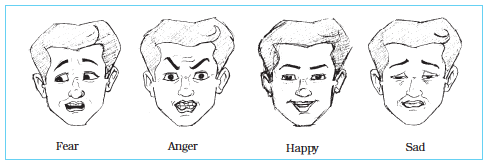

Do you get to know that your friend is happy or sad or indifferent? Does s/he understand your feelings? Emotion is an internal experience not directly observable by others. Emotions are inferred from verbal and non-verbal expressions. These verbal and non-verbal expressions act as the channels of communication and enable an individual to express one’s emotions and to understand the feelings of others.

Fig.9.8 : Sketches of Facial Expressions of Emotions

Culture and Emotional Expression

The verbal channel of communication is composed of spoken words as well as other vocal features of speech like pitch and loudness of the voice. These non-verbal aspects of the voice and temporal characteristics of speech are called ‘paralanguage’. Other non-verbal channels include facial expression, kinetic (gesture, posture, movement of the body) and proximal (physical distance during face-to-face interaction) behaviours. Facial expression is the most common channel of emotional communication. The amount and kind of information conveyed by the face is easy to comprehend as the face is exposed to the full view of others (see Fig.9.8). Facial expressions can convey the intensity as well as the pleasantness or unpleasantness of the individual’s emotional state. Facial expressions play an important role in our everyday lives. There has been some research evidence supporting Darwin’s view that facial expressions for basic emotions (joy, fear, anger, disgust, sadness, and surprise) are inborn and universal.

Bodily movements further facilitate the communication of emotions. Can you feel the difference between your body movements when you feel angry and movements when you feel shy? Theatre and drama provide an excellent opportunity to understand the impact of body movements in communicating emotions. The roles of gestures and proximal behaviours are also significant. You must have seen how in Indian classical dances like Bharatanatyam, Odissi, Kuchipudi, Kathak and others, emotions are expressed with the help of movements of eyes, legs, and fingers. The dancers are trained rigorously in the grammar of body movement and non-verbal communication to express joy, sorrow, love, anger, and various other forms of emotional states.

The processes involved in emotions have been known to be influenced by culture. Current research has dealt more specifically with the issue of universality or culture specificity of emotions. Most of this research has been carried out on the facial expression of emotions as the face is open to easy observation, is relatively free from complexity and provides a link between subjective experience and overt expression of an emotion. Still it must be emphasised that emotions are conveyed not only via face. A felt emotion may be communicated through other non-verbal channels as well, for example, gaze behaviour, gestures, paralanguage, and proximal behaviour. The emotional meaning conveyed via gestures (body language) varies from culture to culture. For example, in China, a handclap is an expression of worry or disappointment, and anger is expressed with laughter. Silence has also been found to convey different meanings for different cultures. For example, in India, deep emotions are sometimes communicated via silence. This may convey embarrassment during communication in Western countries. Cultural differences have also been found in the gaze behaviour. It has been observed that the Latin Americans and the Southern Europeans direct their gaze to the eyes of the interactant. Asians, in particular, Indians and Pakistanis, prefer a peripheral gaze (looking away from the conversational partner) during an interaction. The physical space (proximity) also divulges different kinds of emotional meaning during emotional exchanges. The Americans, for example, do not prefer an interaction too close; the Oriental Indians consider a close space comfortable for an interaction. In fact, the touching behaviour in physical proximity is considered reflective of emotional warmth. For example, it was observed that the Arabs experience alienation during an interaction with the North Americans who prefer to be interacted from outside the olfactory (too close) zone.

Activity 9.3

Emotional expressions vary in their intensity as well as variety. In your spare time, try collecting from old magazines or newspapers as many pictures of different individuals expressing various emotions. Make picture cards pasting each photograph on a piece of cardboard and number them. You can make a set of such cards that represent different emotional expressions. Involve a group of your friends in the activity. Display these cards one by one to your friends and ask them to identify the emotions being portrayed. Note down the responses and notice how your friends differ from each other in labelling the same emotion. You can also try to categorise the pictures using categories like positive and negative, intense and subtle emotions, and so on. Try to notice how people differ from each other in expressing the same emotion. What could be the reason for such differences? Discuss in class.

Culture and Emotional Labeling

Basic emotions also vary in the extent of elaboration and categorical labels. The Tahitian language includes 46 labels for the English word anger. When asked to label freely, the North American subjects produced 40 different responses for the facial expression of anger and 81 different responses for the facial expression of contempt. The Japanese produced varied emotional labels for facial expressions of happiness (10 labels), anger (8 labels), and disgust (6 labels). Ancient Chinese literature cites seven emotions, namely, joy, anger, sadness, fear, love, dislike, and liking. Ancient Indian literature identifies eight such emotions, namely, love, mirth, energy, wonder, anger, grief, disgust, and fear. In Western literature, certain emotions like happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust are uniformly treated as basic to human beings. Emotions like surprise, contempt, shame, and guilt are not accepted as basic to all.

In brief, it might be said that there are certain basic emotions that are expressed and understood by all despite their cultural and ethnic differences, and there are certain others that are specific to a particular culture. Again, it is important to remember that culture plays a significant role in all processes of emotion. Both expression and experience of emotions are mediated and modified by culture specific ‘display rules’ that delimit the conditions under which an emotion may be expressed and the intensity with which it is displayed.

Managing Negative Emotions

Try living a day in which you do not feel any emotion. You would realise that it is difficult even to imagine a life without emotions. Emotions are a part of our daily life and existence. They form the very fabric of our life and interpersonal relations.

Emotions exist on a continuum. There are various intensities of an emotion that can be experienced by us. You can experience extreme elation or slight happiness, severe grief or just pensiveness. However, most of us usually maintain a balance of emotions.

When faced with a conflicting situation, individuals attempt to adjust and derive a coping mechanism either with task or defense-oriented reactions. These coping patterns help them prevent abnormal emotional reactions such as anxiety, depression etc. Anxiety is a condition that an individual develops in case of failure to adopt an appropriate ego defense. For example, if the individual fails to adhere to a defense of rationalisation for his immoral act (like cheating or stealing), he may develop intense apprehension about the outcomes of such an act. Anxious individuals find it difficult to concentrate or to make decisions even for trivial matters.

The state of depression affects an individual’s ability to think rationally, feel realistically, and work effectively. The condition overwhelms the mood state of the individual. Because of its enduring nature, the individual who suffers from depression develops a variety of symptoms like difficulty in falling asleep, increased level of psychomotor agitation or retardation, decreased ability to think or concentrate, and loss of interest in personal or social activities, etc.

In daily life, we are often faced with conflicting situations. Under demanding and stressful conditions, a lot of negative emotions like fear, anxiety, disgust, etc. develop in an individual to a considerable extent. Such negative emotions, if allowed to prevail for a long time, are likely to affect adversely the person’s psychological and physical health. This is the reason why most of the stress management programmes emphasise emotion management as an integral part of stress management. The major focus of emotion management techniques is the reduction of negative emotions and enhancing positive emotions.

Though most researchers focus their attention only on negative emotions like anger, fear, anxiety, etc., recently the field of ‘Positive Psychology’ has gained much prominence. As the name suggests, positive psychology concerns itself with the study of features that enrich life like, hope, happiness, creativity, courage, optimism, cheerfulness, etc.

Box 9.4 Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

A disaster produces serious disruption of the functioning of human society, resulting in widespread material or environmental loss, which cannot be dealt with immediately with the existing resources. Disaster may be natural (like earthquake/cyclone/tsunami) or man-made (like war). The trauma an individual experiences during a disaster may range from mere perception of such an event to actually encountering it, which may be life threatening. Either of these conditions may lead to development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), where the person tends to re-experience the event through flashbacks and get overwhelming thoughts about the event even after a substantial period of time. This condition makes a person emotionally disturbed and the person fails to adopt an appropriate coping strategy in regular activities. Emotions manifest in uniquely recognisable patterns with maladaptive behaviour (like depression) and autonomic arousal.

Effective emotion management is the key to effective social functioning in modern times. The following tips might prove useful to you for achieving the desired balance of emotions :

• Enhance self-awareness : Be aware of your own emotions and feelings. Try to gain insight into the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of your feelings.

• Appraise the situation objectively : It has been proposed that emotion is preceded by evaluation of the event. If the event is experienced as disturbing, your sympathetic nervous system is activated and you feel stressed. If you do not experience the event as disturbing, then there is no stress. Hence, it is you who decides whether to feel sad and anxious or happy and relaxed.

• Do some self-monitoring : This involves constant or periodic evaluation of your past accomplishments, emotional and physical states, real and vicarious experiences. A positive appraisal would enhance your faith in yourself and lead to enhanced feeling of wellness and contentment.

• Engage in self-modeling : Be the ideal for yourself. Repeatedly observe the best parts of your past performance and use them as an inspiration and motivation to perform better in the future.

• Perceptual reorganisation and cognitive restructuring : Try viewing the events differently and visualise the other side of the coin. Restructure your thoughts to enhance positive and reassuring feelings and eliminate negative thoughts.

• Be creative : Find and develop an interest or a hobby. Engage in an activity that interests and amuses you.

• Develop and nurture good relation-ships : Choose your friends carefully. In the company of happy and cheerful friends you will feel happy in general.

• Have empathy : Try understanding other’s feelings too. Make your relationships meaningful and valuable. Seek as well as provide support mutually.

Box 9.5 Management of Examination Anxiety

For most of us an approaching examination brings about a feeling of a churning stomach and anxiety. In fact, any situation which involves performing a task and the awareness of being evaluated for the performance is an anxiety-provoking situation for most people. A certain level of anxiety is definitely essential as it motivates and pushes us to put up our best performance but a high level of anxiety becomes an impediment in optimum performance and achievement. An anxious individual is highly aroused physiologically and emotionally, and hence is not able to perform to the best of her/his abilities.

An examination is a potentially stress provoking situation and like other stressful situations coping involves two strategies, i.e. Monitoring or taking effective action, and Blunting or avoiding the situation.

Monitoring involves taking effective and direct action to deal with the stressful situation. The following strategies can be used for monitoring :

• Prepare well : Prepare well for the examination and prepare well in advance. Give yourself ample time. Familiarise yourself with the pattern of question papers and frequently asked questions. This gives you a sense of predictability and control and reduces the stress potential of the examination.

• Have a rehearsal : Make yourself go through a mock examination. Ask your friend to test your knowledge. You can also rehearse mentally in your mind. Visualise yourself taking the examination completely relaxed and confident and then passing with flying colours.

• Inoculation : Inoculate yourself against stress. Exposure through rehearsals and role-playing prepares you physically and mentally to face the examination situation better and with confidence.

• Positive thinking : Have faith in yourself. Structure your thoughts with systematically listing the thoughts that worry you and then rationally dealing with them one by one. Emphasise on your strengths. Suggest to yourself to be positive and enthusiastic.

• Seek support : Do not hesitate to ask for help from your friends, parents, teachers or seniors. Talking about a stressful situation to a close person makes one feel light and helps gain insight. The situation may not be as bad as it seems.

On the other hand, blunting strategies involve avoiding the stressful situation. True, avoidance is neither desirable nor possible in an examination situation, but the following techniques may prove useful:

• Relaxation : Learn to relax. Relaxation techniques help you calm your nerves and give you an opportunity to reframe your thoughts. There are many different relaxation techniques. In general, this involves sitting or lying down in a comfortable posture in a quiet place, relaxing your muscles, reducing the external stimulation as well as minimising the flow of thoughts and focusing.

• Exercise : A stressful situation overactivates the sympathetic nervous system. Exercise helps in channelising the excess energy generated by this. A brief period of light exercise or active sport will help you concentrate better on your studies.

• Participate in community service : Help yourself by helping others. By doing community service (for example, helping an intellectually challenged child learn an adaptive skill), you will gain important insights about your own difficulties.

Activity 9.4

Think of an intense emotional experience you have gone through recently and explain the sequence of events. How did you deal with it? Share it with your class.

Managing your Anger

• Recognise the power of your thoughts.

• Realise you alone can control it.

• Do not engage in ‘self-talk that burns’. Do not magnify negative feelings.

• Do not ascribe intentions and ulterior motives to others.

• Resist having irrational beliefs about people and events.

• Try to find constructive ways of expressing your anger. Have control on the degree and duration of anger that you choose to express.

• Look inward not outward for anger control.

• Give yourself time to change. It takes time and effort to change a habit.

Enhancing Positive Emotions

Our emotions have a purpose. They help us adapt to the ever-changing environment and are important for our survival and well-being. Negative emotions like fear, anger or disgust prepare us mentally and physically for taking immediate action towards the stimulus that is threatening. For example, if there was no fear we would have caught a poisonous snake in our hand. Though negative emotions protect us in such situations but excessive or inappropriate use of these emotions can become life threatening to us, as it can harm our immune system and have serious consequences for our health.

Positive emotions such as hope, joy, optimism, contentment, and gratitude energise us and enhance our sense of emotional well-being. When we experience positive affect, we display a greater preference for a large variety of actions and ideas. We can think of more possibilities and options to solve whatever problems we face and thus, we become proactive.

Box 9.6 Emotional Intelligence

Expressions of emotion depend on regulation of emotion for self or others. Persons who are capable of having awareness of emotions for self or others and regulate accordingly are called emotionally intelligent. Persons who fail to do so, deviate and thereby develop abreaction of emotion, resulting in psychopathology of certain kinds.

By emotional intelligence, we understand ‘the ability to monitor one’s own and other’s emotions, to discriminate among them and to use the information to guide one’s thinking and actions’ (Mayer & Salovey, 1999). The concept of emotional intelligence subsumes intrapersonal and interpersonal elements. The intrapersonal element includes factors like self-awareness (ability to keep negative emotions and impulses under control), and self-motivation (the drive to achieve despite setbacks, developing skills to attain targets and taking initiative to act on opportunities). The interpersonal element of emotional intelligence includes two components: social awareness (the awareness and the tendency to appreciate other’s feelings) and social competence (social skills that help to adjust with others, such as team building, conflict management, skills of communicating, etc.).

Psychologists have found that people, who were shown films depicting joy and contentment, came up with more ideas regarding things they would like to do as compared to those who were shown films evoking anger and fear. Positive emotions give us a greater ability to cope with adverse circumstances and quickly return to a normal state. They help us set up long-term plans and goals, and form new relationships. Various ways of enhancing positive emotions are given below:

• Personality traits of optimism, hopefulness, happiness and a positive self-regard.

• Finding positive meaning in dire circumstances.

• Having quality connections with others, and supportive network of close relationships.

• Being engaged in work and gaining mastery.

• A faith that embodies social support, purpose and hope, leading a life of purpose.

• Positive interpretations of most daily events.

KeyTerms

Amygdala, Anxiety, Arousal, Autonomic nervous system, Basic emotions, Biological needs (hunger, thirst, sex), Central nervous system, Conflict, Emotional intelligence, Esteem needs, Examination anxiety, Expression of emotions, Frustration, Hierarchy of needs, Motivation, Motives, Need, Power motive, Psychosocial motives, Self-actualisation, Self-esteem

Summary

• There are two types of motivation, namely, biological, and psychosocial motivation.

• Biological motivation focuses on the innate, biological causes of motivation like hormones, neurotransmitters, brain structures (hypothalamus, limbic system), etc. Examples of biological motivation are hunger, thirst, and sex.

• Psychosocial motivation explains motives resulting mainly from the interaction of the individual with his social environment. Examples of psychosocial motives are need for affiliation, need for achievement, curiosity and exploration, and the need for power.

• Maslow arranged various human needs in an ascending hierarchical order, beginning with the most basic physiological needs, and then safety needs, love and belongingness needs, esteem needs, and finally on the top of the hierarchy is the need for self-actualisation.

• Other concepts related to motivation are frustration and conflicts.

• Emotion is a complex pattern of arousal that involves physiological activation, conscious awareness of feeling, and a specific cognitive label that describes the process.

• Certain emotions are basic like joy, anger, sorrow, surprise, fear, etc. Other emotions are experienced as a result of combination of these emotions.

• Central and autonomic nervous system play a major role in regulating emotions.

• Culture strongly influences the expression and interpretation of emotions.

• Emotion is expressed through verbal and non-verbal channels.

• It is important to manage emotions effectively in order to ensure physical and psychological well-being.

Review Questions

1. Explain the concept of motivation.

2. What are the biological bases of hunger and thirst needs?

3. How do the needs for achievement, affiliation, and power influence the behaviour of adolescents? Explain with examples.

4. What is the basic idea behind Maslow’s hierarchy of needs? Explain with suitable examples.

5. Does physiological arousal precede or follow an emotional experience? Explain.

6. Is it important to consciously interpret and label emotions in order to explain them? Discuss giving suitable examples.

7. How does culture influence the expression of emotions?

8. Why is it important to manage negative emotions? Suggest ways to manage negative emotions.

Project Ideas

1. Using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, analyse what kind of motivational forces might have motivated the great mathematician S.A. Ramanujan and the great shehnai Maestro Ustad Bismillah Khan (Bharat Ratna) to perform exceptionally in their respective fields. Now place yourself and five more known people in terms of need satisfaction. Reflect and discuss.

2. In many households, family members do not eat without bathing first and practise religious fasts. How have different social practices influenced your expression of hunger and thirst? Conduct a survey on five people from different backgrounds and prepare a report.