Table of Contents

Women and men have travelled in search of work, to escape from natural disasters, as traders, merchants, soldiers, priests, pilgrims, or driven by a sense of adventure. Those who visit or come to stay in a new land invariably encounter a world that is different: in terms of the landscape or physical environment as well as customs, languages, beliefs and practices of people. Many of them try to adapt to these differences; others, somewhat exceptional, note them carefully in accounts, generally recording what they find unusual or remarkable. Unfortunately, we have practically no accounts of travel left by women, though we know that they travelled.

Fig. 5.1a

Paan leaves

The accounts that survive are often varied in terms of their subject matter. Some deal with affairs of the court, while others are mainly focused on religious issues, or architectural features and monuments. For example, one of the most important descriptions of the city of Vijayanagara (Chapter 7) in the fifteenth century comes from Abdur Razzaq Samarqandi, a diplomat who came visiting from Herat.

In a few cases, travellers did not go to distant lands. For example, in the Mughal Empire (Chapters 8 and 9), administrators sometimes travelled within the empire and recorded their observations. Some of them were interested in looking at popular customs and the folklore and traditions of their own land.

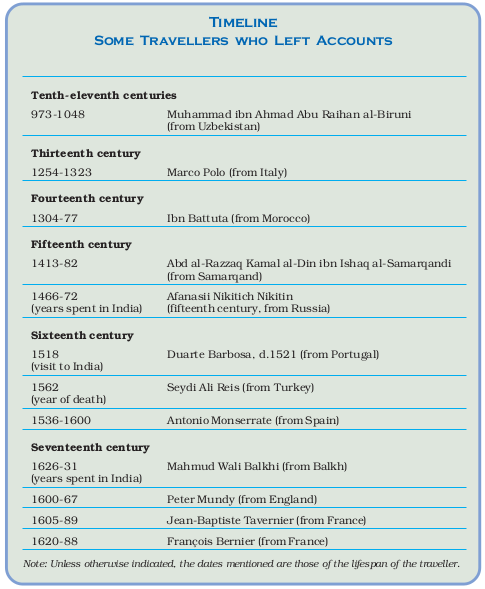

In this chapter we shall see how our knowledge of the past can be enriched through a consideration of descriptions of social life provided by travellers who visited the subcontinent, focusing on the accounts of three men: Al-Biruni who came from Uzbekistan (eleventh century), Ibn Battuta who came from Morocco, in northwestern Africa (fourteenth century) and the Frenchman François Bernier (seventeenth century).

Fig. 5.1b

A coconut

The coconut and the paan

were things that struck many travellers as unusual.

As these authors came from vastly different social and cultural environments, they were often more attentive to everyday activities and practices which were taken for granted by indigenous writers, for whom these were routine matters, not worthy of being recorded. It is this difference in perspective that makes the accounts of travellers interesting. Who did these travellers write for? As we will see, the answers vary from one instance to the next.

Source 1

Al-Biruni’s objectives

Al-Biruni described his work as:

a help to those who want to[ discuss religious questions with them (the Hindus), and as a repertory of information to those who want to associate with them.

⇒ Read the excerpt from Al-Biruni (Source 5) and discuss whether his work met these objectives.

1. Al-Biruni and the Kitab-ul-Hind

1.1 From Khwarizm to the Punjab

Al-Biruni was born in 973, in Khwarizm in present-day Uzbekistan. Khwarizm was an important centre of learning, and Al-Biruni received the best education available at the time. He was well versed in several languages: Syriac, Arabic, Persian, Hebrew and Sanskrit. Although he did not know Greek, he was familiar with the works of Plato and other Greek philosophers, having read them in Arabic translations. In 1017, when Sultan Mahmud invaded Khwarizm, he took several scholars and poets back to his capital, Ghazni; Al-Biruni was one of them. He arrived in Ghazni as a hostage, but gradually developed a liking for the city, where he spent the rest of his life until his death at the age of 70.

It was in Ghazni that Al-Biruni developed an interest in India. This was not unusual. Sanskrit works on astronomy, mathematics and medicine had been translated into Arabic from the eighth century onwards. When the Punjab became a part of the Ghaznavid empire, contacts with the local population helped create an environment of mutual trust and understanding. Al-Biruni spent years in the company of Brahmana priests and scholars, learning Sanskrit, and studying religious and philosophical texts. While his itinerary is not clear, it is likely that he travelled widely in the Punjab and parts of northern India.

Travel literature was already an accepted part of Arabic literature by the time he wrote. This literature dealt with lands as far apart as the Sahara desert in the west to the River Volga in the north. So, while few people in India would have read Al-Biruni before 1500, many others outside India may have done so.

Translating texts, sharing ideas

Al-Biruni’s expertise in several languages allowed him to compare languages and translate texts. He translated several Sanskrit works, including Patanjali’s work on grammar, into Arabic. For his Brahmana friends, he translated the works of Euclid (a Greek mathematician) into Sanskrit.

1.2 The Kitab-ul-Hind

Al-Biruni’s Kitab-ul-Hind, written in Arabic, is simple and lucid. It is a voluminous text, divided into 80 chapters on subjects such as religion and philosophy, festivals, astronomy, alchemy, manners and customs, social life, weights and measures, iconography, laws and metrology.

Metrology is the science of measurement.

Generally (though not always), Al-Biruni adopted a distinctive structure in each chapter, beginning with a question, following this up with a description based on Sanskritic traditions, and concluding with a comparison with other cultures. Some present-day scholars have argued that this almost geometric structure, remarkable for its precision and predictability, owed much to his mathematical orientation.

Al-Biruni, who wrote in Arabic, probably intended his work for peoples living along the frontiers of the subcontinent. He was familiar with translations and adaptations of Sanskrit, Pali and Prakrit texts into Arabic – these ranged from fables to works on astronomy and medicine. However, he was also critical about the ways in which these texts were written, and clearly wanted to improve on them.

Hindu

The term “Hindu” was derived from an Old Persian word, used c. sixth-fifth centuries bce, to refer to the region east of the river Sindhu (Indus). The Arabs continued the Persian usage and called this region “al-Hind” and its people “Hindi”. Later the Turks referred to the people east of the Indus as “Hindu”, their land as “Hindustan”, and their language as “Hindavi”. None of these expressions indicated the religious identity of the people. It was much later that the term developed religious connotations.

Discuss...

If Al-Biruni lived in the twenty-first century, which are the area

s of the world where he could have been easily understood, if he still knew the same languages?

Fig. 5.2

An illustration from a thirteenth-century Arabic manuscript showing the Athenian statesman and poet Solon, who lived in the sixth century bce, addressing his students

Notice the clothes they are shown in.

Are these clothes Greek or Arabian?

2. Ibn Battuta’s Rihla

2.1 An early globe-trotter

Ibn Battuta’s book of travels, called Rihla, written in Arabic, provides extremely rich and interesting details about the social and cultural life in the subcontinent in the fourteenth century. This Moroccan traveller was born in Tangier into one of the most respectable and educated families known for their expertise in Islamic religious law or shari‘a. True to the tradition of his family, Ibn Battuta received literary and scholastic education when he was quite young.

Unlike most other members of his class, Ibn Battuta considered experience gained through travels to be a more important source of knowledge than books. He just loved travelling, and went to far-off places, exploring new worlds and peoples. Before he set off for India in 1332-33, he had made pilgrimage trips to Mecca, and had already travelled extensively in Syria, Iraq, Persia, Yemen, Oman and a few trading ports on the coast of East Africa.

Source 2

The bird leaves its nest

This is an excerpt from the Rihla:

My departure from Tangier, my birthplace, took place on Thursday ... I set out alone, having neither fellow-traveller ... nor caravan whose party I might join, but swayed by an overmastering impulse within me and a desire long-cherished in my bosom to visit these illustrious sanctuaries. So I braced my resolution to quit all my dear ones, female and male, and forsook my home as birds forsake their nests ... My age at that time was twenty-two years.

Ibn Battuta returned home in 1354, about 30 years after he had set out.

Travelling overland through Central Asia, Ibn Battuta reached Sind in 1333. He had heard about Muhammad bin Tughlaq, the Sultan of Delhi, and lured by his reputation as a generous patron of arts and letters, set off for Delhi, passing through Multan and Uch. The Sultan was impressed by his scholarship, and appointed him the qazi or judge of Delhi. He remained in that position for several years, until he fell out of favour and was thrown into prison. Once the misunderstanding between him and the Sultan was cleared, he was restored to imperial service, and was ordered in 1342 to proceed to China as the Sultan’s envoy to the Mongol ruler.

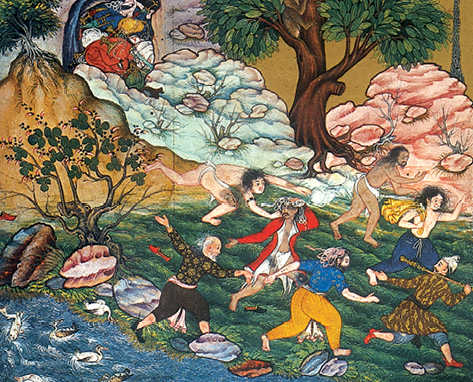

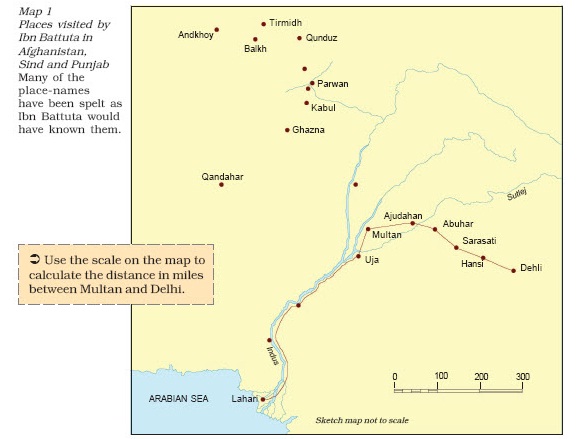

Fig. 5.3

Robbers attacking travellers, a sixteenth-century Mughal painting

How can you distinguish the travellers from the robbers?

With the new assignment, Ibn Battuta proceeded to the Malabar coast through central India. From Malabar he went to the Maldives, where he stayed for eighteen months as the qazi, but eventually decided to proceed to Sri Lanka. He then went back once more to the Malabar coast and the Maldives, and before resuming his mission to China, visited Bengal and Assam as well. He took a ship to Sumatra, and from there another ship for the Chinese port town of Zaytun (now known as Quanzhou). He travelled extensively in China, going as far as Beijing, but did not stay for long, deciding to return home in 1347. His account is often compared with that of Marco Polo, who visited China (and also India) from his home base in Venice in the late thirteenth century.

Fig. 5.4

A boat carrying passengers,

a terracotta sculpture from

a temple in Bengal

(c.seventeenth-eighteenth centuries)

Ibn Battuta meticulously recorded his observations about new cultures, peoples, beliefs, values, etc. We need to bear in mind that this globe-trotter was travelling in the fourteenth century, when it was much more arduous and hazardous to travel than it is today. According to Ibn Battuta, it took forty days to travel from Multan to Delhi and about fifty days from Sind to Delhi. The distance from Daulatabad to Delhi was covered in forty days, while that from Gwalior to Delhi took ten days.

The lonely traveller

Robbers were not the only hazard on long journeys: the traveller could feel homesick, or fall ill. Here is an excerpt from the Rihla:

I was attacked by the fever, and I actually tied myself on the saddle with a turban-cloth in case I should fall off by reason of my weakness ... So at last we reached the town of Tunis, and the townsfolk came out to welcome the shaikh ... and ... the son of the qazi ... On all sides they came forward with greetings and questions to one another, but not a soul said a word of greeting to me, since there was none of them I knew. I felt so sad at heart on account of my loneliness that I could not restrain the tears that started to my eyes, and wept bitterly. But one of the pilgrims, realising the cause of my distress, came up to me with a greeting ...

Travelling was also more insecure: Ibn Battuta was attacked by bands of robbers several times. In fact he preferred travelling in a caravan along with companions, but this did not deter highway robbers. While travelling from Multan to Delhi, for instance, his caravan was attacked and many of his fellow travellers lost their lives; those travellers who survived, including Ibn Battuta, were severely wounded.

2.2 The “enjoyment of curiosities”

As we have seen, Ibn Battuta was an inveterate traveller who spent several years travelling through north Africa, West Asia and parts of Central Asia (he may even have visited Russia), the Indian subcontinent and China, before returning to his native land, Morocco. When he returned, the local ruler issued instructions that his stories be recorded.

Source 3

Education and entertainment

This is what Ibn Juzayy, who was deputed to write what Ibn Battuta dictated, said in his introduction:

A gracious direction was transmitted (by the ruler) that he (Ibn Battuta) should dictate an account of the cities which he had seen in his travel, and of the interesting events which had clung to his memory, and that he should speak of those whom he had met of the rulers of countries, of their distinguished men of learning, and their pious saints. Accordingly, he dictated upon these subjects a narrative which gave entertainment to the mind and delight to the ears and eyes, with a variety of curious particulars by the exposition of which he gave edification and of marvellous things, by referring to which he aroused interest.

Fig. 5.5

An eighteenth-century painting depicting travellers gathered

around a campfire

In the footsteps of Ibn Battuta

In the centuries between 1400 and 1800 visitors to India wrote a number of travelogues in Persian. At the same time, Indian visitors to Central Asia, Iran and the Ottoman empire also sometimes wrote about their experiences. These writers followed in the footsteps of Al-Biruni and Ibn Battuta, and had sometimes read these earlier authors.

Among the best known of these writers were Abdur Razzaq Samarqandi, who visited south India in the 1440s, Mahmud Wali Balkhi, who travelled very widely in the 1620s, and Shaikh Ali Hazin, who came to north India in the 1740s. Some of these authors were fascinated by India, and one of them – Mahmud Balkhi – even became a sort of sanyasi for a time. Others such as Hazin were disappointed and even disgusted with India, where they expected to receive a red carpet treatment. Most of them saw India as a land of wonders.

Discuss...

Compare the objectives of Al-Biruni and Ibn Battuta in writing their accounts.

3. François Bernier A Doctor with a Difference

Once the Portuguese arrived in India in about 1500, a number of them wrote detailed accounts regarding Indian social customs and religious practices. A few of them, such as the Jesuit Roberto Nobili, even translated Indian texts into European languages.

Fig. 5.6

A seventeenth-century painting depicting Bernier in European clothes

Among the best known of the Portuguese writers is Duarte Barbosa, who wrote a detailed account of trade and society in south India. Later, after 1600, we find growing numbers of Dutch, English and French travellers coming to India. One of the most famous was the French jeweller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who travelled to India at least six times. He was particularly fascinated with the trading conditions in India, and compared India to Iran and the Ottoman empire. Some of these travellers, like the Italian doctor Manucci, never returned to Europe, and settled down in India.

François Bernier, a Frenchman, was a doctor, political philosopher and historian. Like many others, he came to the Mughal Empire in search of opportunities. He was in India for twelve years, from 1656 to 1668, and was closely associated with the Mughal court, as a physician to Prince Dara Shukoh, the eldest son of Emperor Shah Jahan, and later as an intellectual and scientist, with Danishmand Khan, an Armenian noble at the Mughal court.

3.1 Comparing “East” and “West”

Bernier travelled to several parts of the country, and wrote accounts of what he saw, frequently comparing what he saw in India with the situation in Europe. He dedicated his major writing to Louis XIV, the king of France, and many of his other works were written in the form of letters to influential officials and ministers. In virtually every instance Bernier described what he saw in India as a bleak situation in comparison to developments in Europe. As we will see, this assessment was not always accurate. However, when his works were published, Bernier’s writings became extremely popular.

Fig. 5.7

A painting depicting Tavernier in Indian clothes

Travelling with the Mughal army

Bernier often travelled with the army. This is an excerpt from his description of the army’s march to Kashmir:

I am expected to keep two good Turkoman horses, and I also take with me a powerful Persian camel and driver, a groom for my horses, a cook and a servant to go before my horse with a flask of water in his hand, according to the custom of the country. I am also provided with every useful article, such as a tent of moderate size, a carpet, a portable bed made of four very strong but light canes, a pillow, a mattress, round leather table-cloths used at meals, some few napkins of dyed cloth, three small bags with culinary utensils which are all placed in a large bag, and this bag is again carried in a very capacious and strong double sack or net made of leather thongs. This double sack likewise contains the provisions, linen and wearing apparel, both of master and servants. I have taken care to lay in a stock of excellent rice for five or six days’ consumption, of sweet biscuits flavoured with anise (a herb), of limes and sugar. Nor have I forgotten a linen bag with its small iron hook for the purpose of suspending and draining dahi or curds; nothing being considered so refreshing in this country as lemonade and dahi.

What are the things from Bernier’s list that you would take on a journey today?

The creation and circulation of ideas about India

The writings of European travellers helped produce an image of India for Europeans through the printing and circulation of their books. Later, after 1750, when Indians like Shaikh Itisamuddin and Mirza Abu Talib visited Europe and confronted this image that Europeans had of their society, they tried to influence it by producing their own version of matters.

Bernier’s works were published in France in 1670-71 and translated into English, Dutch, German and Italian within the next five years. Between 1670 and 1725 his account was reprinted eight times in French, and by 1684 it had been reprinted three times in English. This was in marked contrast to the accounts in Arabic and Persian, which circulated as manuscripts and were generally not published before 1800.

Discuss...

There is a very rich travel literature in Indian languages. Find out about travel writers in the language you use at home. Read one such account and describe the areas visited by the traveller, what s/he saw, and why s/he wrote the account.

4. Making Sense of an Alien World Al-Biruni and the Sanskritic Tradition

4.1 Overcoming barriers to understanding

As we have seen, travellers often compared what they saw in the subcontinent with practices with which they were familiar. Each traveller adopted distinct strategies to understand what they observed. Al-Biruni, for instance, was aware of the problems inherent in the task he had set himself. He discussed several “barriers” that he felt obstructed understanding. The first amongst these was language. According to him, Sanskrit was so different from Arabic and Persian that ideas and concepts could not be easily translated from one language into another.

A language with an enormous range

Al-Biruni described Sanskrit as follows:

If you want to conquer this difficulty (i.e. to learn Sanskrit), you will not find it easy, because the language is of an enormous range, both in words and inflections, something like the Arabic, calling one and the same thing by various names, both original and derivative, and using one and the same word for a variety of subjects, which, in order to be properly understood, must be distinguished from each other by various qualifying epithets.

The second barrier he identified was the difference in religious beliefs and practices. The self-absorption and consequent insularity of the local population according to him, constituted the third barrier. What is interesting is that even though he was aware of these problems, Al-Biruni depended almost exclusively on the works of Brahmanas, often citing passages from the Vedas, the Puranas, the Bhagavad Gita, the works of Patanjali, the Manusmriti, etc., to provide an understanding of Indian society.

4.2 Al-Biruni’s description of the caste system

Al-Biruni tried to explain the caste system by looking for parallels in other societies. He noted that in ancient Persia, four social categories were recognised: those of knights and princes; monks, fire-priests and lawyers; physicians, astronomers and other scientists; and finally, peasants and artisans. In other words, he attempted to suggest that social divisions were not unique to India. At the same time he pointed out that within Islam all men were considered equal, differing only in their observance of piety.

God knows best!

Travellers did not always believe what they were told. When faced with the story of a wooden idol that supposedly lasted for 216,432 years, Al-Biruni asks:

How, then, could wood have lasted such a length of time, and particularly in a place where the air and the soil are rather wet? God knows best!

In spite of his acceptance of the Brahmanical description of the caste system, Al-Biruni disapproved of the notion of pollution. He remarked that everything which falls into a state of impurity strives and succeeds in regaining its original condition of purity. The sun cleanses the air, and the salt in the sea prevents the water from becoming polluted. If it were not so, insisted Al-Biruni, life on earth would have been impossible. The conception of social pollution, intrinsic to the caste system, was according to him, contrary to the laws of nature.

Source 5

The system of varnas

This is Al-Biruni’s account of the system of varnas:

The highest caste are the Brahmana, of whom the books of the Hindus tell us that they were created from the head of Brahman. And as the Brahman is only another name for the force called nature, and the head is the highest part of the … body, the Brahmana are the choice part of the whole genus. Therefore the Hindus consider them as the very best of mankind.

The next caste are the Kshatriya, who were created, as they say, from the shoulders and hands of Brahman. Their degree is not much below that of the Brahmana.

After them follow the Vaishya, who were created from the thigh of Brahman.

The Shudra, who were created from his feet . . .

Between the latter two classes there is no very great distance. Much, however, as these classes differ from each other, they live together in the same towns and villages, mixed together in the same houses and lodgings.

Compare what Al-Biruni wrote with Source 6, Chapter 3. Do you notice any similarities and differences? Do you think Al-Biruni depended only on Sanskrit texts for his information and understanding of Indian society?

As we have seen, Al-Biruni’s description of the caste system was deeply influenced by his study of normative Sanskrit texts which laid down the rules governing the system from the point of view of the Brahmanas. However, in real life the system was not quite as rigid. For instance, the categories defined as antyaja (literally, born outside the system) were often expected to provide inexpensive labour to both peasants and zamindars (see also Chapter 8). In other words, while they were often subjected to social oppression, they were included within economic networks.

Discuss...

How important is knowledge of the language of the area for a traveller from a different region?

5. Ibn Battuta and the Excitement of the Unfamiliar

By the time Ibn Battuta arrived in Delhi in the fourteenth century, the subcontinent was part of a global network of communication that stretched from China in the east to north-west Africa and Europe in the west. As we have seen, Ibn Battuta himself travelled extensively through these lands, visiting sacred shrines, spending time with learned men and rulers, often officiating as qazi, and enjoying the cosmopolitan culture of urban centres where people who spoke Arabic, Persian, Turkish and other languages, shared ideas, information and anecdotes. These included stories about men noted for their piety, kings who could be both cruel and generous, and about the lives of ordinary men and women; anything that was unfamiliar was particularly highlighted in order to ensure that the listener or the reader was suitably impressed by accounts of distant yet accessible worlds.

Sorce 6

Nuts like a man’s head

The following is how Ibn Battuta described the coconut:

These trees are among the most peculiar trees in kind and most astonishing in habit. They look exactly like date-palms, without any difference between them except that the one produces nuts as its fruits and the other produces dates. The nut of a coconut tree resembles a man’s head, for in it are what look like two eyes and a mouth, and the inside of it when it is green looks like the brain, and attached to it is a fibre which looks like hair. They make from this cords with which they sew up ships instead of (using) iron nails, and they (also) make from it cables for vessels.

What are the comparisons that Ibn Battuta makes to give his readers an idea about what coconuts looked like? Do you think these are appropriate? How does he convey a sense that this fruit is unusual? How accurate is his description?

5.1 The coconut and the paan

Some of the best examples of Ibn Battuta’s strategies of representation are evident in the ways in which he described the coconut and the paan, two kinds of plant produce that were completely unfamiliar to his audience.

The paan

Read Ibn Battuta’s description of the paan:

The betel is a tree which is cultivated in the same manner as the grape-vine; … The betel has no fruit and is grown only for the sake of its leaves … The manner of its use is that before eating it one takes areca nut; this is like a nutmeg but is broken up until it is reduced to small pellets, and one places these in his mouth and chews them. Then he takes the leaves of betel, puts a little chalk on them, and masticates them along with the betel.

Why do you think this attracted Ibn Battuta’s attention? Is there anything you would like to add to this description?

5.2 Ibn Battuta and Indian cities

Ibn Battuta found cities in the subcontinent full of exciting opportunities for those who had the necessary drive, resources and skills. They were densely populated and prosperous, except for the occasional disruptions caused by wars and invasions. It appears from Ibn Battuta’s account that most cities had crowded streets and bright and colourful markets that were stacked with a wide variety of goods. Ibn Battuta described Delhi as a vast city, with a great population, the largest in India. Daulatabad (in Maharashtra) was no less, and easily rivalled Delhi in size.

What were the architectural features that Ibn Battuta noted?

Compare this description with the illustrations of the city shown in Figs. 5.8 and 5.9.

Source 8

Dehli

Here is an excerpt from Ibn Battuta’s account of Delhi, often spelt as Dehli in texts of the period:

The city of Dehli covers a wide area and has a large population ... The rampart round the city is without parallel. The breadth of its wall is eleven cubits; and inside it are houses for the night sentry and gate-keepers. Inside the ramparts, there are store-houses for storing edibles, magazines, ammunition, ballistas and siege machines.

Fig. 5.8

An arch in Tughlakabad, Delhi

The grains that are stored (in these ramparts) can last for a long time, without rotting ... In the interior of the rampart, horsemen as well as infantrymen move from one end of the city to another. The rampart is pierced through by windows which open on the side of the city, and it is through these windows that light enters inside. The lower part of the rampart is built of stone; the upper part of bricks. It has many towers close to one another. There are twenty eight gates of this city which are called darwaza, and of these, the Budaun darwaza is the greatest; inside the Mandwi darwaza there is a grain market; adjacent to the Gul darwaza there is an orchard ... It (the city of Dehli) has a fine cemetery in which graves have domes over them, and those that do not have a dome, have an arch, for sure. In the cemetery they sow flowers such as tuberose, jasmine, wild rose, etc.; and flowers blossom there in all seasons.

Fig. 5.9

Part of the fortification wall of the settlement

Fig. 5.10

Ikat weaving patterns such as this were adopted and modified at several coastal production centres in the subcontinent and in Southeast Asia.

The bazaars were not only places of economic transactions, but also the hub of social and cultural activities. Most bazaars had a mosque and a temple, and in some of them at least, spaces were marked for public performances by dancers, musicians and singers.

While Ibn Battuta was not particularly concerned with explaining the prosperity of towns, historians have used his account to suggest that towns derived a significant portion of their wealth through the appropriation of surplus from villages. Ibn Battuta found Indian agriculture very productive because of the fertility of the soil, which allowed farmers to cultivate two crops a year. He also noted that the subcontinent was well integrated with inter-Asian networks of trade and commerce, with Indian manufactures being in great demand in both West Asia and Southeast Asia, fetching huge profits for artisans and merchants. Indian textiles, particularly cotton cloth, fine muslins, silks, brocade and satin, were in great demand. Ibn Battuta informs us that certain varieties of fine muslin were so expensive that they could be worn only by the nobles and the very rich.

Source 9

Music in the market

Read Ibn Battuta’s description of Daulatabad:

In Daulatabad there is a market place for male and female singers, which is known as Tarababad. It is one of the greatest and most beautiful bazaars. It has numerous shops and every shop has a door which leads into the house of the owner ... The shops are decorated with carpets and at the centre of a shop there is a swing on which sits the female singer. She is decked with all kinds of finery and her female attendants swing her. In the middle of the market place there stands a large cupola, which is carpeted and decorated and in which the chief of the musicians takes his place every Thursday after the dawn prayers, accompanied by his servants and slaves. The female singers come in successive crowds, sing before him and dance until dusk after which he withdraws. In this bazaar there are mosques for offering prayers ... One of the Hindu rulers ... alighted at the cupola every time he passed by this market place, and the female singers would sing before him. Even some Muslim rulers did the same.

Why do you think Ibn Battuta highlighted these activities in his description?

5.3 A unique system of communication

The state evidently took special measures to encourage merchants. Almost all trade routes were well supplied with inns and guest houses. Ibn Battuta was also amazed by the efficiency of the postal system which allowed merchants to not only send information and remit credit across long distances, but also to dispatch goods required at short notice. The postal system was so efficient that while it took fifty days to reach Delhi from Sind, the news reports of spies would reach the Sultan through the postal system in just five days.

A strange nation?

The travelogue of Abdur Razzaq written in the 1440s is an interesting mixture of emotions and perceptions. On the one hand, he did not appreciate what he saw in the port of Calicut (present-day Kozhikode) in Kerala, which was populated by “a people the likes of whom I had never imagined”, describing them as “a strange nation”.

Later in his visit to India, he arrived in Mangalore, and crossed the Western Ghats. Here he saw a temple that filled him with admiration:

Within three leagues (about nine miles of Mangalore, I saw an idol-house the likes of which is not to be found in all the world. It was a square, approximately ten yards a side, five yards in height, all covered with cast bronze, with four porticos. In the entrance portico was a statue in the likeness of a human being, full stature, made of gold. It had two red rubies for eyes, so cunningly made that you would say it could see. What craft and artisanship!

Source 10

On horse and on foot

This is how Ibn Battuta describes the postal system:

In India the postal system is of two kinds. The horse-post, called uluq, is run by royal horses stationed at a distance of every four miles. The foot-post has three stations per mile; it is called dawa, that is one-third of a mile ... Now, at every third of a mile there is a well-populated village, outside which are three pavilions in which sit men with girded loins ready to start. Each of them carries a rod, two cubits in length, with copper bells at the top. When the courier starts from the city he holds the letter in one hand and the rod with its bells on the other; and he runs as fast as he can. When the men in the pavilion hear the ringing of the bell they get ready. As soon as the courier reaches them, one of them takes the letter from his hand and runs at top speed shaking the rod all the while until he reaches the next dawa. And the same process continues till the letter reaches its destination. This foot-post is quicker than the horse-post; and often it is used to transport the fruits of Khurasan which are much desired in India.

Do you think the foot-post system could have operated throughout the subcontinent?

Discuss...

How did Ibn Battuta handle the problem of describing things or situations to people who

had not seen or experienced them?

6. Bernier and the “Degenerate” East

If Ibn Battuta chose to describe everything that impressed and excited him because of its novelty, François Bernier belonged to a different intellectual tradition. He was far more preoccupied with comparing and contrasting what he saw in India with the situation in Europe in general and France in particular, focusing on situations which he considered depressing. His idea seems to have been to influence policy-makers and the intelligentsia to ensure that they made what he considered to be the “right” decisions.

Bernier’s Travels in the Mughal Empire is marked by detailed observations, critical insights and reflection. His account contains discussions trying to place the history of the Mughals within some sort of a universal framework. He constantly compared Mughal India with contemporary Europe, generally emphasising the superiority of the latter. His representation of India works on the model of binary opposition, where India is presented as the inverse of Europe. He also ordered the perceived differences hierarchically, so that India appeared to be inferior to the Western world.

Widespread poverty

Pelsaert, a Dutch traveller, visited the subcontinent during the early decades of the seventeenth century. Like Bernier, he was shocked to see the widespread poverty, “poverty so great and miserable that the life of the people can be depicted or accurately described only as the home of stark want and the dwelling place of bitter woe”. Holding the state responsible, he says: “So much is wrung from the peasants that even dry bread is scarcely left to fill their stomachs.”

6.1 The question of landownership

According to Bernier, one of the fundamental differences between Mughal India and Europe was the lack of private property in land in the former. He was a firm believer in the virtues of private property, and saw crown ownership of land as being harmful for both the state and its people. He thought that in the Mughal Empire the emperor owned all the land and distributed it among his nobles, and that this had disastrous consequences for the economy and society. This perception was not unique to Bernier, but is found in most travellers’ accounts of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Owing to crown ownership of land, argued Bernier, landholders could not pass on their land to their children. So they were averse to any long-term investment in the sustenance and expansion of production. The absence of private property in land had, therefore, prevented the emergence of the class of “improving” landlords (as in Western Europe) with a concern to maintain or improve the land. It had led to the uniform ruination of agriculture, excessive oppression of the peasantry and a continuous decline in the living standards of all sections of society, except the ruling aristocracy.

Source 11

The poor peasant

An excerpt from Bernier’s description of the peasantry in the countryside:

Of the vast tracts of country constituting the empire of Hindustan, many are little more than sand, or barren mountains, badly cultivated, and thinly populated. Even a considerable portion of the good land remains untilled for want of labourers; many of whom perish in consequence of the bad treatment they experience from Governors. The poor people, when they become incapable of discharging the demands of their rapacious lords, are not only often deprived of the means of subsistence, but are also made to lose their children, who are carried away as slaves. Thus, it happens that the peasantry, driven to despair by so excessive a tyranny, abandon the country.

In this instance, Bernier was participating in contemporary debates in Europe concerning the nature of state and society, and intended that his description of Mughal India would serve as a warning to those who did not recognise the “merits” of private property.

What, according to Bernier, were the problems faced by peasants in the subcontinent? Do you think his description would have served to strengthen his case?

As an extension of this, Bernier described Indian society as consisting of undifferentiated masses of impoverished people, subjugated by a small minority of a very rich and powerful ruling class. Between the poorest of the poor and the richest of the rich, there was no social group or class worth the name. Bernier confidently asserted: “There is no middle state in India.”

Fig. 5.11

Drawings such as this nineteenth-century example often reinforced the notion of an unchanging rural society.

This, then, is how Bernier saw the Mughal Empire – its king was the king of “beggars and barbarians”; its cities and towns were ruined and contaminated with “ill air”; and its fields, “overspread with bushes” and full of “pestilential marishes”. And, all this was because of one reason: crown ownership of land.

Curiously, none of the Mughal official documents suggest that the state was the sole owner of land. For instance, Abu’l Fazl, the sixteenth-century official chronicler of Akbar’s reign, describes the land revenue as “remunerations of sovereignty”, a claim made by the ruler on his subjects for the protection he provided rather than as rent on land that he owned. It is possible that European travellers regarded such claims as rent because land revenue demands were often very high. However, this was actually not a rent or even a land tax, but a tax on the crop (for more details, see Chapter 8).

Source 12

A warning for Europe

Bernier warned that if European kings followed the Mughal model:

Their kingdoms would be very far from being well-cultivated and peopled, so well built, so rich, so polite and flourishing as we see them. Our kings are otherwise rich and powerful; and we must avow that they are much better and more royally served. They would soon be kings of deserts and solitudes, of beggars and barbarians, such as those are whom I have been representing (the Mughals) … We should find the great Cities and the great Burroughs (boroughs) rendered uninhabitable because of ill air, and to fall to ruine (ruin) without any bodies (anybody) taking care of repairing them; the hillocks abandon’d, and the fields overspread with bushes, or fill’d with pestilential marishes (marshes), as hath been already intimated.

How does Bernier depict a scenario of doom?Once you have read Chapters 8 and 9, return to this description and analyse it again.

Bernier’s descriptions influenced Western theorists from the eighteenth century onwards. The French philosopher Montesquieu, for instance, used this account to develop the idea of oriental despotism, according to which rulers in Asia (the Orient or the East) enjoyed absolute authority over their subjects, who were kept in conditions of subjugation and poverty, arguing that all land belonged to the king and that private property was non-existent. According to this view, everybody, except the emperor and his nobles, barely managed to survive.

This idea was further developed as the concept of the Asiatic mode of production by Karl Marx in the nineteenth century. He argued that in India (and other Asian countries), before colonialism, surplus was appropriated by the state. This led to the emergence of a society that was composed of a large number of autonomous and (internally) egalitarian village communities. The imperial court presided over these village communities, respecting their autonomy as long as the flow of surplus was unimpeded. This was regarded as a stagnant system.

However, as we will see (Chapter 8), this picture of rural society was far from true. In fact, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, rural society was characterised by considerable social and economic differentiation. At one end of the spectrum were the big zamindars, who enjoyed superior rights in land and, at the other, the “untouchable” landless labourers. In between was the big peasant, who used hired labour and engaged in commodity production, and the smaller peasant who could barely produce for his subsistence.

6.2 A more complex social reality

While Bernier’s preoccupation with projecting the Mughal state as tyrannical is obvious, his descriptions occasionally hint at a more complex social reality. For instance, he felt that artisans had no incentive to improve the quality of their manufactures, since profits were appropriated by the state. Manufactures were, consequently, everywhere in decline. At the same time, he conceded that vast quantities of the world’s precious metals flowed into India, as manufactures were exported in exchange for gold and silver. He also noticed the existence of a prosperous merchant community, engaged in long-distance exchange.

Fig. 5.12

A gold spoon studded with emeralds and rubies, an example of the dexterity of Mughal artisans

Source 13

A different socio-economic scenario

Read this excerpt from Bernier’s description of both agriculture and craft production:

It is important to observe, that of this vast tract of country, a large portion is extremely fertile; the large kingdom of Bengale (Bengal), for instance, surpassing Egypt itself, not only in the production of rice, corn, and other necessaries of life, but of innumerable articles of commerce which are not cultivated in Egypt; such as silks, cotton, and indigo. There are also many parts of the Indies, where the population is sufficiently abundant, and the land pretty well tilled; and where the artisan, although naturally indolent, is yet compelled by necessity or otherwise to employ himself in manufacturing carpets, brocades, embroideries, gold and silver cloths, and the various sorts of silk and cotton goods, which are used in the country or exported abroad.

It should not escape notice that gold and silver, after circulating in every other quarter of the globe, come at length to be swallowed up, lost in some measure, in Hindustan.

In what ways is the description in this excerpt different from that in Source 11?

In fact, during the seventeenth century about 15 per cent of the population lived in towns. This was, on average, higher than the proportion of urban population in Western Europe in the same period. In spite of this Bernier described Mughal cities as “camp towns”, by which he meant towns that owed their existence, and depended for their survival, on the imperial camp. He believed that these came into existence when the imperial court moved in and rapidly declined when it moved out. He suggested that they did not have viable social and economic foundations but were dependent on imperial patronage.

As in the case of the question of landownership, Bernier was drawing an oversimplified picture. There were all kinds of towns: manufacturing towns, trading towns, port-towns, sacred centres, pilgrimage towns, etc. Their existence is an index of the prosperity of merchant communities and professional classes.

Source 14

The imperial karkhanas

Bernier is perhaps the only historian who provides a detailed account of the working of the imperial karkhanas or workshops:

Large halls are seen at many places, called karkhanas or workshops for the artisans. In one hall, embroiderers are busily employed, superintended by a master. In another, you see the goldsmiths; in a third, painters; in a fourth, varnishers in lacquer-work; in a fifth, joiners, turners, tailors and shoe-makers; in a sixth, manufacturers of silk, brocade and fine muslins …

The artisans come every morning to their karkhanas where they remain employed the whole day; and in the evening return to their homes. In this quiet regular manner, their time glides away; no one aspiring for any improvement in the condition of life wherein he happens to be born.

How does Bernier convey a sense that although there was a great deal of activity, there was little progress?

Merchants often had strong community or kin ties, and were organised into their own caste-cum-occupational bodies. In western India these groups were called mahajans, and their chief, the sheth. In urban centres such as Ahmedabad the mahajans were collectively represented by the chief of the merchant community who was called the nagarsheth.

Other urban groups included professional classes such as physicians (hakim or vaid), teachers (pundit or mulla), lawyers (wakil), painters, architects, musicians, calligraphers, etc. While some depended on imperial patronage, many made their living by serving other patrons, while still others served ordinary people in crowded markets or bazaars.

Discuss...

Why do you think scholars like Bernier chose to compare India with Europe?

7. Women Slaves, Sati and Labourers

Travellers who left written accounts were generally men who were interested in and sometimes intrigued by the condition of women in the subcontinent. Sometimes they took social inequities for granted as a “natural” state of affairs. For instance, slaves were openly sold in markets, like any other commodity, and were regularly exchanged as gifts. When Ibn Battuta reached Sind he purchased “horses, camels and slaves” as gifts for Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq. When he reached Multan, he presented the governor with, “a slave and horse together with raisins and almonds”. Muhammad bin Tughlaq, informs Ibn Battuta, was so happy with the sermon of a preacher named Nasiruddin that he gave him “a hundred thousand tankas (coins) and two hundred slaves”.

It appears from Ibn Battuta’s account that there was considerable differentiation among slaves. Some female slaves in the service of the Sultan were experts in music and dance, and Ibn Battuta enjoyed their performance at the wedding of the Sultan’s sister. Female slaves were also employed by the Sultan to keep a watch on his nobles.

Source 15

Slave women

Ibn Battuta informs us:

It is the habit of the emperor ... to keep with every noble, great or small, one of his slaves who spies on the nobles. He also appoints female scavengers who enter the houses unannounced; and to them the slave girls communicate all the information they possess.

Most female slaves were captured in raids and expeditions.

Slaves were generally used for domestic labour, and Ibn Battuta found their services particularly indispensable for carrying women and men on palanquins or dola. The price of slaves, particularly female slaves required for domestic labour, was very low, and most families who could afford to do so kept at least one or two of them.

Contemporary European travellers and writers often highlighted the treatment of women as a crucial marker of difference between Western and Eastern societies. Not surprisingly, Bernier chose the practice of sati for detailed description. He noted that while some women seemed to embrace death cheerfully, others were forced to die.

Source 16

The child sati

This is perhaps one of the most poignant descriptions by Bernier:

At Lahore I saw a most beautiful young widow sacrificed, who could not, I think, have been more than twelve years of age. The poor little creature appeared more dead than alive when she approached the dreadful pit: the agony of her mind cannot be described; she trembled and wept bitterly; but three or four of the Brahmanas, assisted by an old woman who held her under the arm, forced the unwilling victim toward the fatal spot, seated her on the wood, tied her hands and feet, lest she should run away, and in that situation the innocent creature was burnt alive. I found it difficult to repress my feelings and to prevent their bursting forth into clamorous and unavailing rage …

However, women’s lives revolved around much else besides the practice of sati. Their labour was crucial in both agricultural and non-agricultural production. Women from merchant families participated in commercial activities, sometimes even taking mercantile disputes to the court of law. It therefore seems unlikely that women were confined to the private spaces of their homes.

You may have noticed that travellers’ accounts provide us with a tantalising glimpse of the lives of men and women during these centuries. However, their observations were often shaped by the contexts from which they came. At the same time, there were many aspects of social life that these travellers did not notice.

Also relatively unknown are the experiences and observations of men (and possibly women) from the subcontinent who crossed seas and mountains and ventured into lands beyond the subcontinent. What did they see and hear? How were their relations with peoples of distant lands shaped? What were the languages they used? These and other questions will hopefully be systematically addressed by historians in the years to come.

Discuss...

Why do you think the lives of ordinary women workers did not attract the attention of travellers such as Ibn Battuta and Bernier?

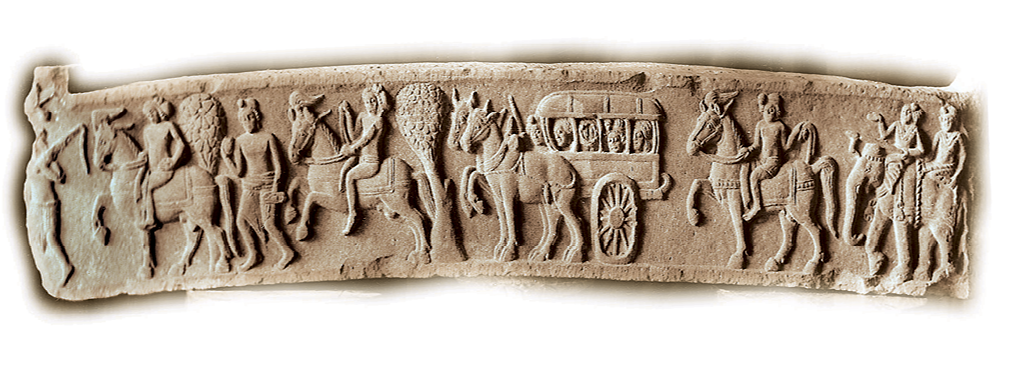

Fig. 5.13

A sculpted panel from Mathura depicting travellers

What are the various modes of transport that are shown?

Answer in100-150 words

1. Write a note on the Kitab-ul-Hind.

2. Compare and contrast the perspectives from which Ibn Battuta and Bernier wrote their accounts of their travels in India.

3. Discuss the picture of urban centres that emerges from Bernier’s account.

4. Analyse the evidence for slavery provided by Ibn Battuta.

5. What were the elements of the practice of sati that drew the attention of Bernier?

Write a short essay (about 250-300 words) on the following:

6. Discuss Al-Biruni’s understanding of the caste system.

7. Do you think Ibn Battuta’s account is useful in arriving at an understanding of life in contemporary urban centres? Give reasons for your answer.

8. Discuss the extent to which Bernier’s account enables historians to reconstruct contemporary rural society.

9. Read this excerpt from Bernier:

Numerous are the instances of handsome pieces of workmanship made by persons destitute of tools, and who can scarcely be said to have received instruction from a master. Sometimes they imitate so perfectly articles of European manufacture that the difference between the original and copy can hardly be discerned. Among other things, the Indians make excellent muskets, and fowling-pieces, and such beautiful gold ornaments that it may be doubted if the exquisite workmanship of those articles can be exceeded by any European goldsmith. I have often admired the beauty, softness, and delicacy of their paintings.

List the crafts mentioned in the passage. Compare these with the descriptions of artisanal activity in the chapter.

Map work

10. On an outline map of the world mark the countries visited by Ibn Battuta. What are the seas that he may have crossed?

Projects (choose one)

11. Interview any one of your older relatives (mother/father/grandparents/uncles/aunts) who has travelled outside your town or village. Find out (a) where they went, (b) how they travelled, (c) how long did it take, (d) why did they travel (e) and did they face any difficulties. List as many similarities and differences that they may have noticed between their place of residence and the place they visited, focusing on language, clothes, food, customs, buildings, roads, the lives of men and women. Write a report on your findings.

12. For any one of the travellers mentioned in the chapter, find out more about his life and writings. Prepare a report on his travels, noting in particular how he described society, and comparing these descriptions with the excerpts included in the chapter.

Fig. 5.14

A painting depicting travellers at rest

If you would like to know more, read:

Muzaffar Alam and Sanjay Subrahmanyam. 2006.

Indo-Persian Travels in the Age of Discoveries, 1400-1800. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Catherine Asher and Cynthia Talbot. 2006.

India Before Europe.

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

François Bernier. nd.

Travels in the Mogul Empire

ad 1656-1668.

Low Price Publications,

New Delhi.

H.A.R. Gibb (ed.). 1993.

The Travels of Ibn Battuta. Munshiram Manoharlal, Delhi.

Mushirul Hasan (ed.). 2005.

Westward Bound:

Travels of Mirza Abu Talib.

Oxford University Press,

New Delhi.

H.K. Kaul (ed.). 1997.

Travellers’ India – an Anthology.

Oxford University Press,

New Delhi.

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier. 1993.

Travels in India.

Munshiram Manoharlal, Delhi.

For more information, you could visit:

www.edumaritime.org