Table of Contents

Fig. 9.1

The mausoleum of Timur at Samarqand, 1404

The rulers of the Mughal Empire saw themselves as appointed by Divine Will to rule over a large and heterogeneous populace. Although this grand vision was often circumscribed by actual political circumstances, it remained important. One way of transmitting this vision was through the writing of dynastic histories. The Mughal kings commissioned court historians to write accounts. These accounts recorded the events of the emperor’s time. In addition, their writers collected vast amounts of information from the regions of the subcontinent to help the rulers govern their domain.

Modern historians writing in English have termed this genre of texts chronicles, as they present a continuous chronological record of events. Chronicles are an indispensable source for any scholar wishing to write a history of the Mughals. At one level they were a repository of factual information about the institutions of the Mughal state, painstakingly collected and classified by individuals closely connected with the court. At the same time these texts were intended as conveyors of meanings that the Mughal rulers sought to impose on their domain. They therefore give us a glimpse into how imperial ideologies were created and disseminated. This chapter will look at the workings of this rich and fascinating dimension of the Mughal Empire.

1. The Mughals and Their Empire

The name Mughal derives from Mongol. Though today the term evokes the grandeur of an empire, it was not the name the rulers of the dynasty chose for themselves. They referred to themselves as Timurids, as descendants of the Turkish ruler Timur on the paternal side. Babur, the first Mughal ruler, was related to Ghenghiz Khan from his mother’s side. He spoke Turkish and referred derisively to the Mongols as barbaric hordes.

During the sixteenth century, Europeans used the term Mughal to describe the Indian rulers of this branch of the family. Over the past centuries the word has been frequently used – even the name Mowgli, the young hero of Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book, is derived from it.

The empire was carved out of a number of regional states of India through conquests and political alliances between the Mughals and local chieftains. The founder of the empire, Zahiruddin Babur, was driven from his Central Asian homeland, Farghana, by the warring Uzbeks. He first established himself at Kabul and then in 1526 pushed further into the Indian subcontinent in search of territories and resources to satisfy the needs of the members of his clan.

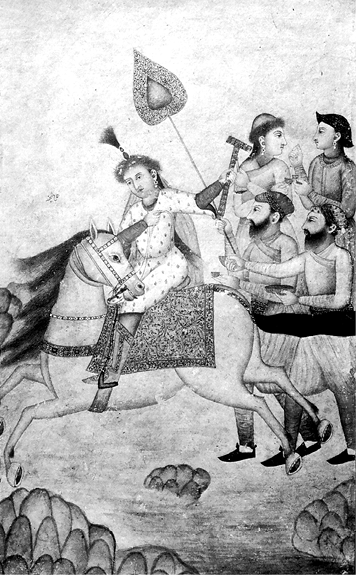

Fig. 9.2

An eighteenth-century depiction of Humayun’s wife Nadira crossing the desert of Rajasthan

His successor, Nasiruddin Humayun (1530-40, 1555-56) expanded the frontiers of the empire, but lost it to the Afghan leader Sher Shah Sur, who drove him into exile. Humayun took refuge in the court of the Safavid ruler of Iran. In 1555 Humayun defeated the Surs, but died a year later.

Many consider Jalaluddin Akbar (1556-1605) the greatest of all the Mughal emperors, for he not only expanded but also consolidated his empire, making it the largest, strongest and richest kingdom of his time. Akbar succeeded in extending the frontiers of the empire to the Hindukush mountains, and checked the expansionist designs of the Uzbeks of Turan (Central Asia) and the Safavids of Iran. Akbar had three fairly able successors in Jahangir (1605-27), Shah Jahan (1628-58) and Aurangzeb (1658-1707), much as their characters varied. Under them the territorial expansion continued, though at a much reduced pace. The three rulers maintained and consolidated the various instruments of governance.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the institutions of an imperial structure were created. These included effective methods of administration and taxation. The visible centre of Mughal power was the court. Here political alliances and relationships were forged, status and hierarchies defined. The political system devised by the Mughals was based on a combination of military power and conscious policy to accommodate the different traditions they encountered in the subcontinent.

Discuss...

Find out whether the state in which you live formed part of the Mughal Empire.

Were there any changes in the area as a result of the establishment of the empire? If your state was not part of the empire, find out more about contemporary regional rulers – their origins and policies. What kind of records did they maintain?

After 1707, following the death of Aurangzeb, the power of the dynasty diminished. In place of the vast apparatus of empire controlled from Delhi, Agra or Lahore – the different capital cities – regional powers acquired greater autonomy. Yet symbolically the prestige of the Mughal ruler did not lose its aura. In 1857 the last scion of this dynasty, Bahadur Shah Zafar II, was overthrown by the British.

2. The Production of Chronicles

Chronicles commissioned by the Mughal emperors are an important source for studying the empire and its court. They were written in order to project a vision of an enlightened kingdom to all those who came under its umbrella. At the same time they were meant to convey to those who resisted the rule of the Mughals that all resistance was destined to fail. Also, the rulers wanted to ensure that there was an account of their rule for posterity.

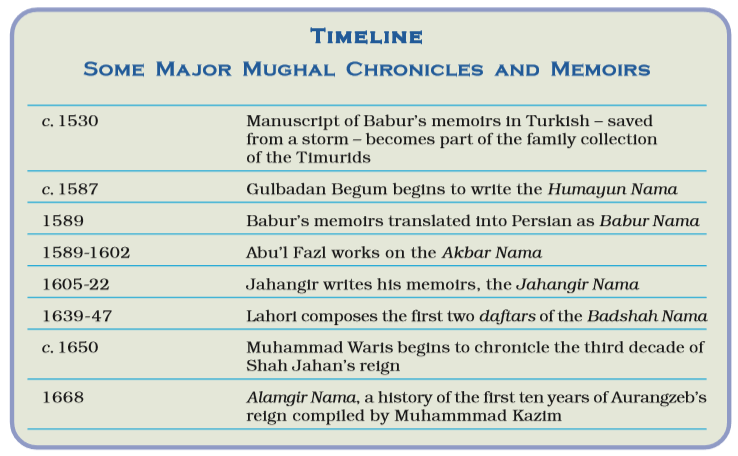

The authors of Mughal chronicles were invariably courtiers. The histories they wrote focused on events centred on the ruler, his family, the court and nobles, wars and administrative arrangements. Their titles, such as the Akbar Nama, Shahjahan Nama, Alamgir Nama, that is, the story of Akbar, Shah Jahan and Alamgir (a title of the Mughal ruler Aurangzeb), suggest that in the eyes of their authors the history of the empire and the court was synonymous with that of the emperor.

Chaghtai Turks traced descent from the eldest son of Ghengiz Khan.

2.1 From Turkish to Persian

Mughal court chronicles were written in Persian. Under the Sultans of Delhi it flourished as a language of the court and of literary writings, alongside north Indian languages, especially Hindavi and its regional variants. As the Mughals were Chaghtai Turks by origin, Turkish was their mother tongue. Their first ruler Babur wrote poetry and his memoirs in this language.

It was Akbar who consciously set out to make Persian the leading language of the Mughal court. Cultural and intellectual contacts with Iran, as well as a regular stream of Iranian and Central Asian migrants seeking positions at the Mughal court, might have motivated the emperor to adopt the language. Persian was elevated to a language of empire, conferring power and prestige on those who had a command of it. It was spoken by the king, the royal household and the elite at court. Further, it became the language of administration at all levels so that accountants, clerks and other functionaries also learnt it.

The flight of the written word

In Abu’l Fazl’s words:

The written word may embody the wisdom of bygone ages and may become a means to intellectual progress. The spoken word goes to the heart of those who are present to hear it. The written word gives wisdom to those who are near and far. If it was not for the written word, the spoken word would soon die, and no keepsake would be left us from those who are passed away. Superficial observers see in the letter a dark figure, but the deep-sighted see in it a lamp of wisdom (chirag-i shinasai). The written word looks black, notwithstanding the thousand rays within it, or it is a light with a mole on it that wards off the evil eye. A letter (khat) is the portrait of wisdom; a rough sketch from the realm of ideas; a dark light ushering in day; a black cloud pregnant with knowledge; speaking though dumb; stationary yet travelling; stretched on the sheet, and yet soaring upwards.

Even when Persian was not directly used, its vocabulary and idiom heavily influenced the language of official records in Rajasthani and Marathi and even Tamil. Since the people using Persian in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries came from many different regions of the subcontinent and spoke other Indian languages, Persian too became Indianised by absorbing local idioms. A new language, Urdu, sprang from the interaction of Persian with Hindavi.

Mughal chronicles such as the Akbar Nama were written in Persian, others, like Babur’s memoirs, were translated from the Turkish into the Persian Babur Nama. Translations of Sanskrit texts such as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana into Persian were commissioned by the Mughal emperors. The Mahabharata was translated as the Razmnama (Book of Wars).

2.2 The making of manuscripts

All books in Mughal India were manuscripts, that is, they were handwritten. The centre of manuscript production was the imperial kitabkhana. Although kitabkhana can be translated as library, it was a scriptorium, that is, a place where the emperor’s collection of manuscripts was kept and new manuscripts were produced.

The creation of a manuscript involved a number of people performing a variety of tasks. Paper makers were needed to prepare the folios of the manuscript, scribes or calligraphers to copy the text, gilders to illuminate the pages, painters to illustrate scenes from the text, bookbinders to gather the individual folios and set them within ornamental covers. The finished manuscript was seen as a precious object, a work of intellectual wealth and beauty. It exemplified the power of its patron, the Mughal emperor, to bring such beauty into being.

At the same time some of the people involved in the actual production of the manuscript also got recognition in the form of titles and awards. Of these, calligraphers and painters held a high social standing while others, such as paper makers or bookbinders, have remained anonymous artisans.

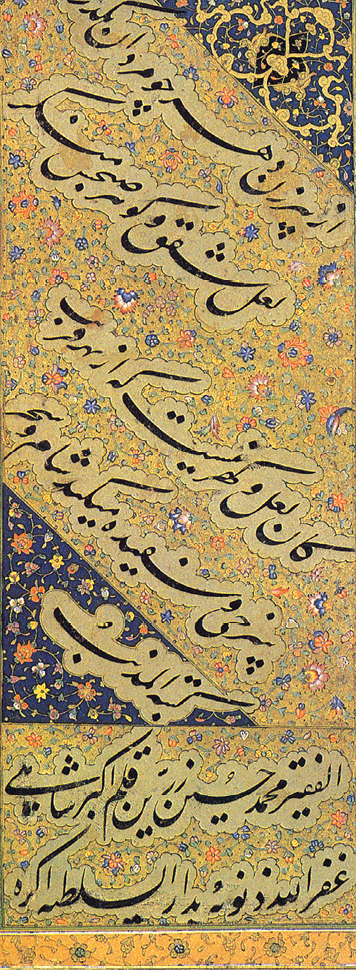

Fig. 9.3

A folio in nastaliq, the work of Muhammad Husayn of Kashmir

(c.1575-1605), one of the finest calligraphers at Akbar’s court, who was honoured with the title “zarrin qalam” (golden pen) in recognition of the perfectly proportioned curvature of his letters

The calligrapher has signed his name on the lower section of

the page, taking up almost

one-fourth of its space.

Calligraphy, the art of handwriting, was considered a skill of great importance. It was practised using different styles. Akbar’s favourite was the nastaliq, a fluid style with long horizontal strokes. It is written using a piece of trimmed reed with a tip of five to 10 mm called qalam, dipped in carbon ink (siyahi). The nib of the qalam is usually split in the middle to facilitate the absorption of ink.

Discuss...

In what ways do you think the production of books today is similar to or different from the ways in which Mughal chronicles were produced?

3. The Painted Image

As we read in the previous section, painters too were involved in the production of Mughal manuscripts. Chronicles narrating the events of a Mughal emperor’s reign contained, alongside the written text, images that described an event in visual form. When scenes or themes in a book were to be given visual expression, the scribe left blank spaces on nearby pages; paintings, executed separately by artists, were inserted to accompany what was described in words. These paintings were miniatures, and could therefore be passed around for viewing and mounting on the pages of manuscripts.

Paintings served not only to enhance the beauty of a book, but were believed to possess special powers of communicating ideas about the kingdom and the power of kings in ways that the written medium could not. The historian Abu’l Fazl described painting as a “magical art”: in his view it had the power to make inanimate objects look as if they possessed life.

The production of paintings portraying the emperor, his court and the people who were part of it, was a source of constant tension between rulers and representatives of the Muslim orthodoxy, the ulama. The latter did not fail to invoke the Islamic prohibition of the portrayal of human beings enshrined in the Qur’an as well as the hadis, which described an incident from the life of the Prophet Muhammad. Here the Prophet is cited as having forbidden the depiction of living beings in a naturalistic manner as it would suggest that the artist was seeking to appropriate the power of creation. This was a function that was believed to belong exclusively to God.

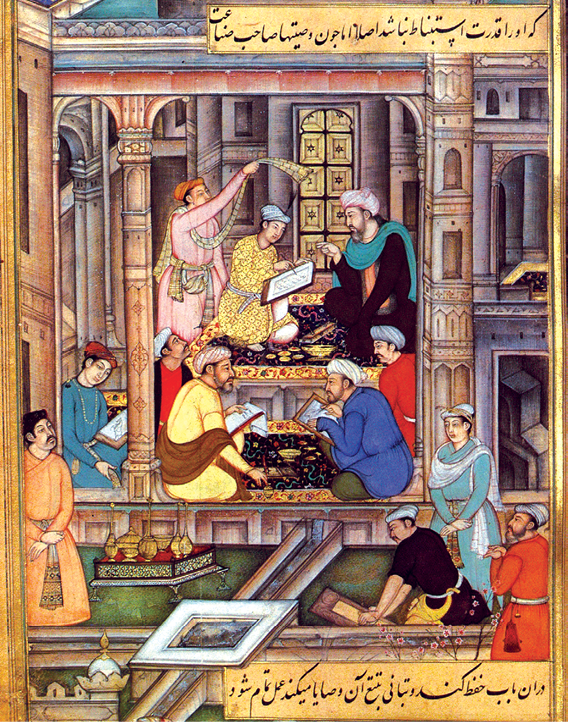

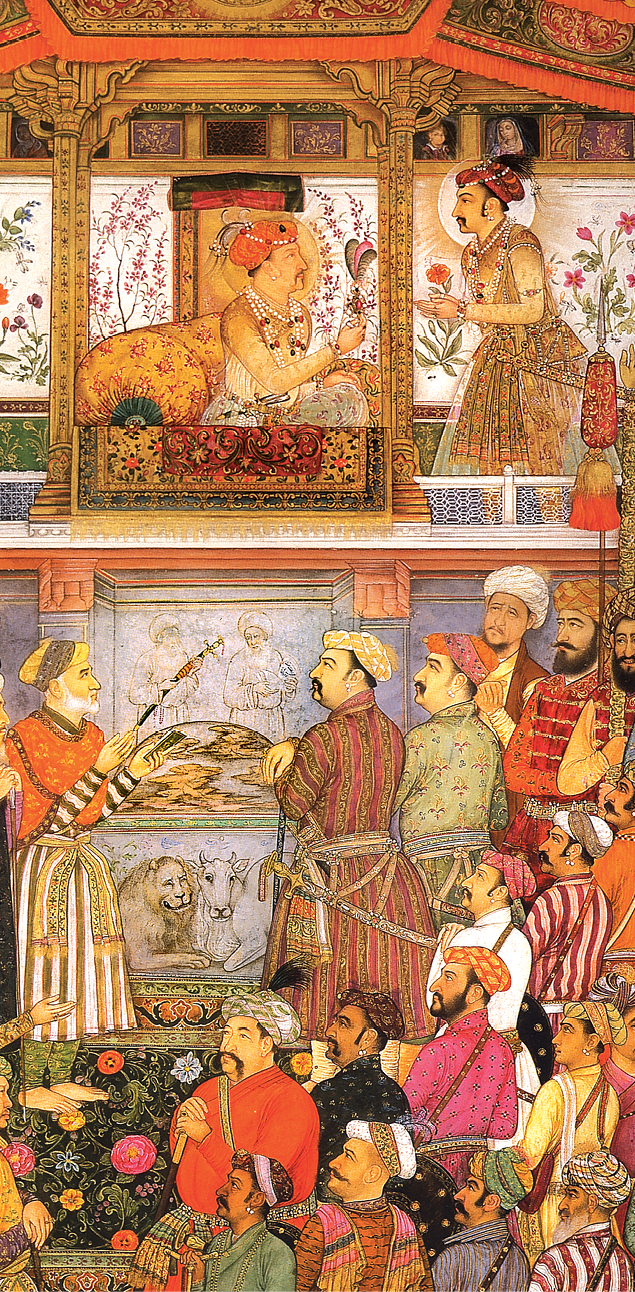

Fig. 9.4

A Mughal kitabkhana

Source 1

In praise of taswir

Abu’l Fazl held the art of painting in high esteem:

Drawing the likeness of anything is called taswir. His Majesty from his earliest youth, has shown a great predilection for this art, and gives it every encouragement, as he looks upon it as a means both of study and amusement. A very large number of painters have been set to work. Each week, several supervisors and clerks of the imperial workshop submit before the emperor the work done by each artist, and His Majesty gives a reward and increases the monthly salaries of the artists according to the excellence displayed. … Most excellent painters are now to be found, and masterpieces, worthy of a Bihzad, may be placed at the side of the wonderful works of the European painters who have attained worldwide fame. The minuteness in detail, the general finish and the boldness of execution now observed in pictures are incomparable; even inanimate objects look as if they have life. More than a hundred painters have become famous masters of the art. This is especially true of the Hindu artists. Their pictures surpass our conception of things. Few, indeed, in the whole world are found equal to them

Why did Abu’l Fazl consider the art of painting important? How did he seek to legitimise this art?

Yet interpretations of the shari‘a changed with time. The body of Islamic tradition was interpreted in different ways by various social groups. Frequently each group put forward an understanding of tradition that would best suit their political needs. Muslim rulers in many Asian regions during centuries of empire building regularly commissioned artists to paint their portraits and scenes of life in their kingdoms. The Safavid kings of Iran, for example, patronised the finest artists, who were trained in workshops set up at court. The names of painters – such as that of Bihzad – contributed to spreading the cultural fame of the Safavid court far and wide.

Artists from Iran also made their way to Mughal India. Some were brought to the Mughal court, as in the case of Mir Sayyid Ali and Abdus Samad, who were made to accompany Emperor Humayun to Delhi. Others migrated in search of opportunities to win patronage and prestige. A conflict between the emperor and the spokesmen of orthodox Muslim opinion on the question of visual representations of living beings was a source of tension at the Mughal court. Akbar’s court historian Abu’l Fazl cites the emperor as saying: “There are many that hate painting, but such men I dislike. It appears to me that an artist has a unique way of recognising God when he must come to feel that he cannot bestow life on his work ...”

Discuss...

Compare the painter’s representation (Fig. 9.4) of literary and artistic production with that of Abu’l Fazl (Source 1).

4. The Akbar Nama and the Badshah Nama

Among the important illustrated Mughal chronicles the Akbar Nama and Badshah Nama (The Chronicle of a King) are the most well known. Each manuscript contained an average of 150 full- or double-page paintings of battles, sieges, hunts, building construction, court scenes, etc.

The author of the Akbar Nama, Abu’l Fazl grew up in the Mughal capital of Agra. He was widely read in Arabic, Persian, Greek philosophy and Sufism. Moreover, he was a forceful debater and independent thinker who consistently opposed the views of the conservative ulama. These qualities impressed Akbar, who found Abu’l Fazl ideally suited as an adviser and a spokesperson for his policies. One major objective of the emperor was to free the state from the control of religious orthodoxy. In his role as court historian, Abu’l Fazl both shaped and articulated the ideas associated with the reign of Akbar.

Beginning in 1589, Abu’l Fazl worked on the Akbar Nama for thirteen years, repeatedly revising the draft. The chronicle is based on a range of sources, including actual records of events (waqai), official documents and oral testimonies of knowledgeable persons.

The Akbar Nama is divided into three books of which the first two are chronicles. The third book is the Ain-i Akbari. The first volume contains the history of mankind from Adam to one celestial cycle of Akbar’s life (30 years). The second volume closes in the forty- sixth regnal year (1601) of Akbar. The very next year Abu’l Fazl fell victim to a conspiracy hatched by Prince Salim, and was murdered by his accomplice, Bir Singh Bundela.

The Akbar Nama was written to provide a detailed description of Akbar’s reign in the traditional diachronic sense of recording politically significant events across time, as well as in the more novel sense of giving a synchronic picture of all aspects of Akbar’s empire – geographic, social, administrative and cultural – without reference to chronology. In the Ain-i Akbari the Mughal Empire is presented as having a diverse population consisting of Hindus, Jainas, Buddhists and Muslims and a composite culture.

Abu’l Fazl wrote in a language that was ornate and which attached importance to diction and rhythm, as texts were often read aloud. This Indo-Persian style was patronised at court, and there were a large number of writers who wanted to write like Abu’l Fazl.

A diachronic account traces developments over time, whereas a synchronic account depicts one or several situations at one particular moment or point of time.

A pupil of Abu’l Fazl, Abdul Hamid Lahori is known as the author of the Badshah Nama. Emperor Shah Jahan, hearing of his talents, commissioned him to write a history of his reign modelled on the Akbar Nama. The Badshah Nama is this official history in three volumes (daftars) of ten lunar years each. Lahori wrote the first and second daftars comprising the first two decades of the emperor’s rule (1627-47); these volumes were later revised by Sadullah Khan, Shah Jahan’s wazir. Infirmities of old age prevented Lahori from proceeding with the third decade which was then chronicled by the historian Waris.

Travels of the Badshah Nama

Gifting of precious manuscripts was an established diplomatic custom under the Mughals. In emulation of this, the Nawab of Awadh gifted the illustrated Badshah Nama to King George III in 1799. Since then it has been preserved in the English Royal Collections, now at Windsor Castle.

In 1994, conservation work required the bound manuscript to be taken apart. This made it possible to exhibit the paintings, and in 1997 for the first time, the Badshah Nama paintings were shown in exhibitions in New Delhi, London and Washington.

During the colonial period, British administrators began to study Indian history and to create an archive of knowledge about the subcontinent to help them better understand the people and the cultures of the empire they sought to rule. The Asiatic Society of Bengal, founded by Sir William Jones in 1784, undertook the editing, printing and translation of many Indian manuscripts.

Edited versions of the Akbar Nama and Badshah Nama were first published by the Asiatic Society in the nineteenth century. In the early twentieth century the Akbar Nama was translated into English by Henry Beveridge after years of hard labour. Only excerpts of the Badshah Nama have been translated into English to date; the text in its entirety still awaits translation.

Discuss...

Find out whether there was a tradition of illustrating manuscripts in your town or village. Who prepared these manuscripts? What were the subjects that they dealt with? How were these manuscripts preserved?

5. The Ideal Kingdom

5.1 A divine light

Court chroniclers drew upon many sources to show that the power of the Mughal kings came directly from God. One of the legends they narrated was that of the Mongol queen Alanqua, who was impregnated by a ray of sunshine while resting in her tent. The offspring she bore carried this Divine Light and passed it on from generation to generation.

Abu’l Fazl placed Mughal kingship as the highest station in the hierarchy of objects receiving light emanating from God (farr-i izadi). Here he was inspired by a famous Iranian sufi, Shihabuddin Suhrawardi (d. 1191) who first developed this idea. According to this idea, there was a hierarchy in which the Divine Light was transmitted to the king who then became the source of spiritual guidance for his subjects.

Paintings that accompanied the narrative of the chronicles transmitted these ideas in a way that left a lasting impression on the minds of viewers. Mughal artists, from the seventeenth century onwards, began to portray emperors wearing the halo, which they saw on European paintings of Christ and the Virgin Mary to symbolise the light of God.

The transmission of notions of luminosity

The origins of Suhrawardi’s philosophy went back to Plato’s Republic, where God is represented by the symbol of the sun. Suhrawardi’s writings were universally read in the Islamic world. They were studied by Shaikh Mubarak, who transmitted their ideas to his sons, Faizi and Abu’l Fazl, who were trained under him.

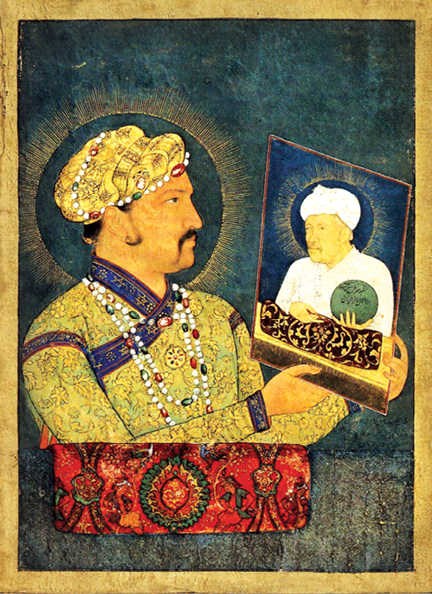

Fig. 9.5

This painting by Abu’l Hasan shows Jahangir dressed in resplendent clothes and jewels, holding up a portrait of his father Akbar.

Akbar is dressed in white, associated in sufi traditions with the enlightened soul. He proffers

a globe, symbolic of dynastic authority.

In the Mughal empire there was no law laying down which of the emperor’s sons would succeed to the throne. This meant that every dynastic change was accompanied and decided by a fratricidal war. Towards the end of Akbar’s reign, Prince Salim revolted against his father, seized power and assumed the title of Jahangir.

How does this painting describe the relationship between father and son? Why do you think Mughal artists frequently portrayed emperors against dark or dull backgrounds? What are the sources of light in this painting?

5.2 A unifying force

Mughal chronicles present the empire as comprising many different ethnic and religious communities – Hindus, Jainas, Zoroastrians and Muslims. As the source of all peace and stability the emperor stood above all religious and ethnic groups, mediated among them, and ensured that justice and peace prevailed. Abu’l Fazl describes the ideal of sulh-i kul (absolute peace) as the cornerstone of enlightened rule. In sulh-i kul all religions and schools of thought had freedom of expression but on condition that they did not undermine the authority of the state or fight among themselves.

The ideal of sulh-i kul was implemented through state policies – the nobility under the Mughals was a composite one comprising Iranis, Turanis, Afghans, Rajputs, Deccanis – all of whom were given positions and awards purely on the basis of their service and loyalty to the king. Further, Akbar abolished the tax on pilgrimage in 1563 and jizya in 1564 as the two were based on religious discrimination. Instructions were sent to officers of the empire to follow the precept of sulh-i kul in administration.

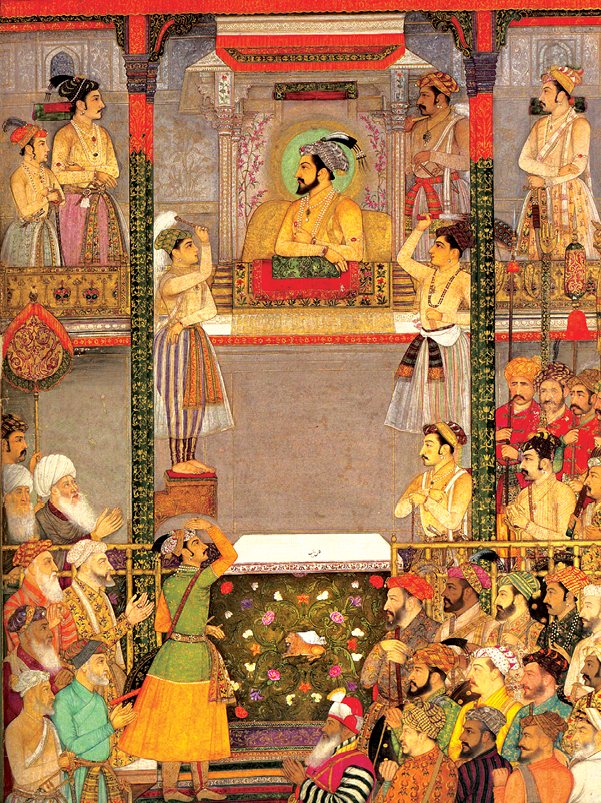

Fig. 9.6

Jahangir presenting Prince Khurram with a turban jewel

Scene from the Badshah Nama painted by the artist Payag,

c.1640.

All Mughal emperors gave grants to support the building and maintenance of places of worship. Even when temples were destroyed during war, grants were later issued for their repair – as we know from the reigns of Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb. However, during the reign of the latter, the jizya was re-imposed on non-Muslim subjects.

5.3 Just sovereignty as social contract

Abu’l Fazl defined sovereignty as a social contract: the emperor protects the four essences of his subjects, namely, life (jan), property (mal), honour (namus) and faith (din), and in return demands obedience and a share of resources. Only just sovereigns were thought to be able to honour the contract with power and Divine guidance.

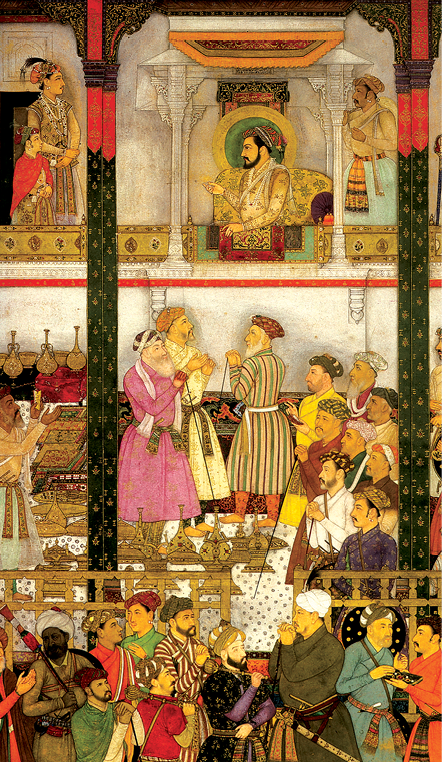

Fig. 9.7

Jahangir shooting the figure of poverty, painting by the artist

Abu’l Hasan

The artist has enveloped the target in a dark cloud to suggest that this is not a real person, but a human form used to symbolise an abstract quality. Such a mode of personification in art and literature is termed allegory.

The Chain of Justice is shown descending from heaven.This is how Jahangir described the Chain of Justice in his memoirs:

After my accession, the first order that I gave was for the fastening up of the Chain

of Justice, so that if those engaged in the administration of justice should delay or practise hypocrisy in the matter of those seeking justice, the oppressed might come to this chain and shake it so

that its noise might attract attention. The chain was made of pure gold, 30 gaz in length and containing 60 bells.

Identify and interpret the symbols in the painting. Summarise the message of this painting.

A number of symbols were created for visual representation of the idea of justice which came to stand for the highest virtue of Mughal monarchy. One of the favourite symbols used by artists was the motif of the lion and the lamb (or goat) peacefully nestling next to each other. This was meant to signify a realm where both the strong and the weak could exist in harmony. Court scenes from the illustrated Badshah Nama place such motifs in a niche directly below the emperor’s throne (see Fig. 9.6).

Discuss...

Why was justice regarded as such an important virtue of monarchy in the Mughal Empire?

6. Capitals and Courts

6.1 Capital cities

The heart of the Mughal Empire was its capital city, where the court assembled. The capital cities of the Mughals frequently shifted during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Babur took over the Lodi capital of Agra, though during the four years of his reign the court was frequently on the move. During the 1560s Akbar had the fort of Agra constructed with red sandstone quarried from the adjoining regions.

In the 1570s he decided to build a new capital, Fatehpur Sikri. One of the reasons prompting this may have been that Sikri was located on the direct road to Ajmer, where the dargah of Shaikh Muinuddin Chishti had become an important pilgrimage centre. The Mughal emperors entered into a close relationship with sufis of the Chishti silsila. Akbar commissioned the construction of a white marble tomb for Shaikh Salim Chishti next to the majestic Friday mosque at Sikri. The enormous arched gateway (Buland Darwaza) was meant to remind visitors of the Mughal victory in Gujarat. In 1585 the capital was transferred to Lahore to bring the north-west under greater control and Akbar closely watched the frontier for thirteen years.

Fig. 9.8

The Buland Darwaza,

Fatehpur Sikri

Shah Jahan pursued sound fiscal policies and accumulated enough money to indulge his passion for building. Building activity in monarchical cultures, as you have seen in the case of earlier rulers, was the most visible and tangible sign of dynastic power, wealth and prestige. In the case of Muslim rulers it was also considered an act of piety.

In 1648 the court, army and household moved from Agra to the newly completed imperial capital, Shahjahanabad. It was a new addition to the old residential city of Delhi, with the Red Fort, the Jama Masjid, a tree-lined esplanade with bazaars (Chandni Chowk) and spacious homes for the nobility. Shah Jahan’s new city was appropriate to a more formal vision of a grand monarchy.

6.2 The Mughal court

The physical arrangement of the court, focused on the sovereign, mirrored his status as the heart of society. Its centrepiece was therefore the throne, the takht, which gave physical form to the function of the sovereign as axis mundi. The canopy, a symbol of kingship in India for a millennium, was believed to separate the radiance of the sun from that of the sovereign.

Chronicles lay down with great precision the rules defining status amongst the Mughal elites. In court, status was determined by spatial proximity to the king. The place accorded to a courtier by the ruler was a sign of his importance in the eyes of the emperor. Once the emperor sat on the throne, no one was permitted to move from his position or to leave without permission. Social control in court society was exercised through carefully defining in full detail the forms of address, courtesies and speech which were acceptable in court. The slightest infringement of etiquette was noticed and punished on the spot.

Axis mundi is a Latin phrase for a pillar or pole that is visualised as the support of the earth.

Source 2

Darbar-i Akbari

Abu’l Fazl gives a vivid account of Akbar’s darbar:

Whenever His Majesty (Akbar) holds court (darbar) a large drum is beaten, the sounds of which are accompanied by Divine praise. In this manner, people of all classes receive notice. His Majesty’s sons and grandchildren, the grandees of the Court, and all other men who have admittance, attend to make the kornish, and remain standing in their proper places. Learned men of renown and skilful mechanics pay their respects; and the officers of justice present their reports. His Majesty, with his usual insights, gives orders, and settles everything in a satisfactory manner. During the whole time, skilful gladiators and wrestlers from all countries hold themselves in readiness, and singers, male and female, are in waiting. Clever jugglers and funny tumblers also are anxious to exhibit their dexterity and agility.

Describe the main activities taking place in the darbar.

Kornish was a form of ceremonial salutation in which the courtier placed the palm of his right hand against his forehead and bent his head. It suggested that the subject placed his head – the seat of the senses and the mind – into the hand of humility, presenting it to the royal assembly

The forms of salutation to the ruler indicated the person’s status in the hierarchy: deeper prostration represented higher status. The highest form of submission was sijda or complete prostration. Under Shah Jahan these rituals were replaced with chahar taslim and zaminbos (kissing the ground).

Chahar taslim is a mode of salutation which begins with placing the back of the right hand on the ground, and raising it gently till the person stands erect, when he puts the palm of his hand upon the crown of his head. It is done four (chahar) times. Taslim literally means submission.

The protocols governing diplomatic envoys at the Mughal court were equally explicit. An ambassador presented to the Mughal emperor was expected to offer an acceptable form of greeting – either by bowing deeply or kissing the ground, or else to follow the Persian custom of clasping one’s hands in front of the chest. Thomas Roe, the English envoy of James I, simply bowed before Jahangir according to European custom, and further shocked the court by demanding a chair.

Shab-i barat is the full moon night on the 14 Shaban, the eighth month of the hijri calendar, and is celebrated with prayers and fireworks in the subcontinent. It is the night when the destinies of the Muslims for the coming year are said to be determined and sins forgiven.

The emperor began his day at sunrise with personal religious devotions or prayers, and then appeared on a small balcony, the jharoka, facing the east. Below, a crowd of people (soldiers, merchants, craftspersons, peasants, women with sick children) waited for a view, darshan, of the emperor. Jharoka darshan was introduced by Akbar with the objective of broadening the acceptance of the imperial authority as part of popular faith.

The jewelled throne

This is how Shah Jahan’s jewelled throne (takht-i murassa) in the hall of public audience in the Agra palace is described in the Badshah Nama:

This gorgeous structure has a canopy supported by twelve-sided pillars and measures five cubits in height from the flight of steps to the overhanging dome. On His Majesty’s coronation, he had commanded that 86 lakh worth of gems and precious stones, and one lakh tolas of gold worth another 14 lakh, should be used in decorating it. … The throne was completed in the course of seven years, and among the precious stones used upon it was a ruby worth one lakh of rupees that Shah Abbas Safavi had sent to the late emperor Jahangir. And on this ruby were inscribed the names of the great emperor Timur Sahib-i qiran, Mirza Shahrukh, Mirza Ulugh Beg, and Shah Abbas as well as the names of the emperors Akbar, Jahangir, and that of His Majesty himself.

Fig. 9.9

Shah Jahan honouring Prince Aurangzeb at Agra before his wedding, painting by Payag

in the Badshah Nama

Identify the emperor. Aurangzeb is shown dressed in a yellow jama (upper garment) and green jacket with little blossoms. How is he placed and what does his gesture to his father suggest? How are the courtiers shown? Can you locate figures with big turbans to the left? These are depictions of scholars.

After spending an hour at the jharoka, the emperor walked to the public hall of audience (diwan-i am) to conduct the primary business of his government. State officials presented reports and made requests. Two hours later, the emperor was in the diwan-i khas to hold private audiences and discuss confidential matters. High ministers of state placed their petitions before him and tax officials presented their accounts. Occasionally, the emperor viewed the works of highly reputed artists or building plans of architects (mimar).

Fig. 9.10

Prince Khurram being weighed in precious metals in a ceremony called jashn-i wazn or tula dan (from Jahangir’s memoirs)

On special occasions such as the anniversary of accession to the throne, Id, Shab-i barat and Holi, the court was full of life. Perfumed candles set in rich holders and palace walls festooned with colourful hangings made a tremendous impression on visitors. The Mughal kings celebrated three major festivals a year: the solar and lunar birthdays of the monarch and Nauroz, the Iranian New Year on the vernal equinox. On his birthdays, the monarch was weighed against various commodities which were then distributed in charity.

Fig. 9.11a

Fig. 9.11b

Dara Shukoh’s wedding

Weddings were celebrated lavishly in the imperial household. In 1633 the wedding of Dara Shukoh and Nadira, the daughter of Prince Parwez, was arranged by Princess Jahanara and Sati un Nisa Khanum, the chief maid of the late empress,

Mumtaz Mahal. An exhibition of the wedding gifts was arranged in the diwan-i am. In the afternoon the emperor and the ladies of the harem paid a visit to it, and in the evening nobles were allowed access. The bride’s mother similarly arranged her presents in the same hall and Shah Jahan went to see them. The hinabandi (application of henna dye) ceremony was performed in the diwan-i khas.

Betel leaf (paan), cardamom and dry fruit were distributed among the attendants of the court.

The total cost of the wedding was Rs 32 lakh, of which Rs six lakh was contributed by the imperial treasury, Rs 16 lakh by Jahanara (including the amount earlier set aside by Mumtaz Mahal) and the rest by the bride’s mother. These paintings from the Badshah Nama depict some of the activities associated with the occasion.

Describe what you see in the pictures.

6.3 Titles and gifts

Grand titles were adopted by the Mughal emperors at the time of coronation or after a victory over an enemy. High-sounding and rhythmic, they created an atmosphere of awe in the audience when announced by ushers (naqib). Mughal coins carried the full title of the reigning emperor with regal protocol.

The granting of titles to men of merit was an important aspect of Mughal polity. A man’s ascent in the court hierarchy could be traced through the titles he held. The title Asaf Khan for one of the highest ministers originated with Asaf, the legendary minister of the prophet king Sulaiman (Solomon). The title Mirza Raja was accorded by Aurangzeb to his two highest-ranking nobles, Jai Singh and Jaswant Singh. Titles could be earned or paid for. Mir Khan offered Rs one lakh to Aurangzeb for the letter alif, that is A, to be added to his name to make it Amir Khan.

Other awards included the robe of honour (khilat), a garment once worn by the emperor and imbued with his benediction. One gift, the sarapa (“head to foot”), consisted of a tunic, a turban and a sash (patka). Jewelled ornaments were often given as gifts by the emperor. The lotus blossom set with jewels (padma murassa) was given only in exceptional circumstances.

A courtier never approached the emperor empty handed: he offered either a small sum of money (nazr) or a large amount (peshkash). In diplomatic relations, gifts were regarded as a sign of honour and respect. Ambassadors performed the important function of negotiating treaties and relationships between competing political powers. In such a context gifts had an important symbolic role. Thomas Roe was disappointed when a ring he had presented to Asaf Khan was returned to him for the reason that it was worth merely 400 rupees.

Discuss...

Are some of the rituals and practices associated with the Mughals followed by present-day political leaders?

7. The Imperial Household

The term “harem” is frequently used to refer to the domestic world of the Mughals. It originates in the Persian word haram, meaning a sacred place. The Mughal household consisted of the emperor’s wives and concubines, his near and distant relatives (mother, step- and foster-mothers, sisters, daughters, daughters-in-law, aunts, children, etc.), and female servants and slaves. Polygamy was practised widely in the Indian subcontinent, especially among the ruling groups.

Both for the Rajput clans as well as the Mughals marriage was a way of cementing political relationships and forging alliances. The gift of territory was often accompanied by the gift of a daughter in marriage. This ensured a continuing hierarchical relationship between ruling groups. It was through the link of marriage and the relationships that developed as a result that the Mughals were able to form a vast kinship network that linked them to important groups and helped to hold a vast empire together.

In the Mughal household a distinction was maintained between wives who came from royal families (begams), and other wives (aghas) who were not of noble birth. The begams, married after receiving huge amounts of cash and valuables as dower (mahr), naturally received a higher status and greater attention from their husbands than did aghas. The concubines (aghacha or the lesser agha) occupied the lowest position in the hierarchy of females intimately related to royalty. They all received monthly allowances in cash, supplemented with gifts according to their status. The lineage-based family structure was not entirely static. The agha and the aghacha could rise to the position of a begam depending on the husband’s will, and provided that he did not already have four wives. Love and motherhood played important roles in elevating such women to the status of legally wedded wives.

Fig. 9.13

Part of the inner apartments in Fatehpur Sikri

Apart from wives, numerous male and female slaves populated the Mughal household. The tasks they performed varied from the most mundane to those requiring skill, tact and intelligence. Slave eunuchs (khwajasara) moved between the external and internal life of the household as guards, servants, and also as agents for women dabbling in commerce.

After Nur Jahan, Mughal queens and princesses began to control significant financial resources. Shah Jahan’s daughters Jahanara and Roshanara enjoyed an annual income often equal to that of high imperial mansabdars. Jahanara, in addition, received revenues from the port city of Surat, which was a lucrative centre of overseas trade.

Describe the activities that the artist has depicted in each of the sections of the painting. On the basis of the tasks being performed by different people, identify the members of the imperial establishment that make up the scene.

Control over resources enabled important women of the Mughal household to commission buildings and gardens. Jahanara participated in many architectural projects of Shah Jahan’s new capital, Shahjahanabad (Delhi). Among these was an imposing double-storeyed caravanserai with a courtyard and garden. The bazaar of Chandni Chowk, the throbbing centre of Shahjahanabad, was designed by Jahanara.

An interesting book giving us a glimpse into the domestic world of the Mughals is the Humayun Nama written by Gulbadan Begum. Gulbadan was the daughter of Babur, Humayun’s sister and Akbar’s aunt. Gulbadan could write fluently in Turkish and Persian. When Akbar commissioned Abu’l Fazl to write a history of his reign, he requested his aunt to record her memoirs of earlier times under Babur and Humayun, for Abu’l Fazl to draw upon.

What Gulbadan wrote was no eulogy of the Mughal emperors. Rather she described in great detail the conflicts and tensions among the princes and kings and the important mediating role elderly women of the family played in resolving some of these conflicts.

Fig. 9.14

Birth of Prince Salim at Fatehpur Sikri, painted by Ramdas, Akbar Nama

8. The Imperial Officials

8.1 Recruitment and rank

Mughal chronicles, especially the Akbar Nama, have bequeathed a vision of empire in which agency rests almost solely with the emperor, while the rest of the kingdom has been portrayed as following his orders. Yet if we look more closely at the rich information these histories provide about the apparatus of the Mughal state, we may be able to understand the ways in which the imperial organisation was dependent on several different institutions to be able to function effectively. One important pillar of the Mughal state was its corps of officers, also referred to by historians collectively as the nobility.

The nobility was recruited from diverse ethnic and religious groups. This ensured that no faction was large enough to challenge the authority of the state. The officer corps of the Mughals was described as a bouquet of flowers (guldasta) held together by loyalty to the emperor. In Akbar’s imperial service, Turani and Iranian nobles were present from the earliest phase of carving out a political dominion. Many had accompanied Humayun; others migrated later to the Mughal court.

The Mughal nobility

This is how Chandrabhan Barahman described the Mughal nobility in his book Char Chaman (Four Gardens), written during the reign of Shah Jahan:

People from many races (Arabs, Iranians, Turks, Tajiks, Kurds, Tatars, Russians, Abyssinians, and so on) and from many countries (Turkey, Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Arabia, Iran, Khurasan, Turan) – in fact, different groups and classes of people from all societies – have sought refuge in the imperial court, as well as different groups from India, men with knowledge and skills as well as warriors, for example, Bukharis and Bhakkaris, Saiyyads of genuine lineage, Shaikhzadas with noble ancestry, Afghan tribes such as the Lodis, Rohillas, Yusufzai, and castes of Rajputs, who were to be addressed as rana, raja, rao and rayan – i.e. Rathor, Sisodia, Kachhwaha, Hada, Gaur, Chauhan, Panwar, Bhaduriya, Solanki, Bundela, Shekhawat, and all the other Indian tribes, such as Ghakkar, Khokar, Baluchi, and others who wielded the sword, and mansabs from 100 to 7000 zat, likewise landowners from the steppes and mountains, from the regions of Karnataka, Bengal, Assam, Udaipur, Srinagar, Kumaon, Tibet and Kishtwar and so on – whole tribes and groups of them have been privileged to kiss the threshold of the imperial court (i.e. attend the court or find employment).

Two ruling groups of Indian origin entered the imperial service from 1560 onwards: the Rajputs and the Indian Muslims (Shaikhzadas). The first to join was a Rajput chief, Raja Bharmal Kachhwaha of Amber, to whose daughter Akbar got married. Members of Hindu castes inclined towards education and accountancy were also promoted, a famous example being Akbar’s finance minister, Raja Todar Mal, who belonged to the Khatri caste.

Iranians gained high offices under Jahangir, whose politically influential queen, Nur Jahan (d. 1645), was an Iranian. Aurangzeb appointed Rajputs to high positions, and under him the Marathas accounted for a sizeable number within the body of officers.

Nobles at court

The Jesuit priest Father Antonio Monserrate, resident at the court of Akbar, noticed:

In order to prevent the great nobles becoming insolent through the unchallenged enjoyment of power, the King summons them to court and gives them imperious commands, as though they were his slaves. The obedience to these commands ill suits their exalted rank and dignity.

What does Father Monserrate’s observation suggest about the relationship between the Mughal emperor and his officials?

All holders of government offices held ranks (mansabs) comprising two numerical designations: zat which was an indicator of position in the imperial hierarchy and the salary of the official (mansabdar), and sawar which indicated the number of horsemen he was required to maintain in service. In the seventeenth century, mansabdars of 1,000 zat or above ranked as nobles (umara, which is the plural of amir).

The nobles participated in military campaigns with their armies and also served as officers of the empire in the provinces. Each military commander recruited, equipped and trained the main striking arm of the Mughal army, the cavalry. The troopers maintained superior horses branded on the flank by the imperial mark (dagh). The emperor personally reviewed changes in rank, titles and official postings for all except the lowest-ranked officers. Akbar, who designed the mansab system, also established spiritual relationships with a select band of his nobility by treating them as his disciples (murid).

Tajwiz was a petition presented by a nobleman to the emperor, recommending that an applicant be recruited as mansabdar.

For members of the nobility, imperial service was a way of acquiring power, wealth and the highest possible reputation. A person wishing to join the service petitioned through a noble, who presented a tajwiz to the emperor. If the applicant was found suitable a mansab was granted to him. The mir bakhshi (paymaster general) stood in open court on the right of the emperor and presented all candidates for appointment or promotion, while his office prepared orders bearing his seal and signature as well as those of the emperor. There were two other important ministers at the centre: the diwan-i ala (finance minister) and sadr-us sudur (minister of grants or madad-i maash, and in charge of appointing local judges or qazis). The three ministers occasionally came together as an advisory body, but were independent of each other. Akbar with these and other advisers shaped the administrative, fiscal and monetary institutions of the empire.

Nobles stationed at the court (tainat-i rakab) were a reserve force to be deputed to a province or military campaign. They were duty-bound to appear twice daily, morning and evening, to express submission to the emperor in the public audience hall. They shared the responsibility for guarding the emperor and his household round the clock.

8.2 Information and empire

The keeping of exact and detailed records was a major concern of the Mughal administration. The mir bakhshi supervised the corps of court writers (waqia nawis) who recorded all applications and documents presented to the court, and all imperial orders (farman). In addition, agents (wakil) of nobles and regional rulers recorded the entire proceedings of the court under the heading “News from the Exalted Court” (Akhbarat-i Darbar-i Mualla) with the date and time of the court session (pahar). The akhbarat contained all kinds of information such as attendance at the court, grant of offices and titles, diplomatic missions, presents received, or the enquiries made by the emperor about the health of an officer. This information is valuable for writing the history of the public and private lives of kings and nobles.

News reports and important official documents travelled across the length and breadth of the regions under Mughal rule by imperial post. Round-the-clock relays of foot-runners (qasid or pathmar) carried papers rolled up in bamboo containers. The emperor received reports from even distant provincial capitals within a few days. Agents of nobles posted outside the capital and Rajput princes and tributary rulers all assiduously copied these announcements and sent their contents by messenger back to their masters. The empire was connected by a surprisingly rapid information loop for public news.

8.3 Beyond the centre: provincial administration

The division of functions established at the centre was replicated in the provinces (subas) where the ministers had their corresponding subordinates (diwan, bakhshi and sadr). The head of the provincial administration was the governor (subadar) who reported directly to the emperor.

The sarkars, into which each suba was divided, often overlapped with the jurisdiction of faujdars (commandants) who were deployed with contingents of heavy cavalry and musketeers in districts. The local administration was looked after at the level of the pargana (sub-district) by three semi-hereditary officers, the qanungo (keeper of revenue records), the chaudhuri (in charge of revenue collection) and the qazi.

Each department of administration maintained a large support staff of clerks, accountants, auditors, messengers, and other functionaries who were technically qualified officials, functioning in accordance with standardised rules and procedures, and generating copious written orders and records. Persian was made the language of administration throughout, but local languages were used for village accounts.

The Mughal chroniclers usually portrayed the emperor and his court as controlling the entire administrative apparatus down to the village level. Yet, as you have seen (Chapter 8), this could hardly have been a process free of tension. The relationship between local landed magnates, the zamindars, and the representatives of the Mughal emperor was sometimes marked by conflicts over authority and a share of the resources. The zamindars often succeeded in mobilising peasant support against the state.

Discuss...

Read Section 2, Chapter 8 once more and discuss the extent to which the emperor’s presence may have been felt in villages.

9. Beyond the Frontiers

Writers of chronicles list many high-sounding titles assumed by the Mughal emperors. These included general titles such as Shahenshah (King of Kings) or specific titles assumed by individual kings upon ascending the throne, such as Jahangir (World-Seizer), or Shah Jahan (King of the World). The chroniclers often drew on these titles and their meanings to reiterate the claims of the Mughal emperors to uncontested territorial and political control. Yet the same contemporary histories provide accounts of diplomatic relationships and conflicts with neighbouring political powers. These reflect some tension and political rivalry arising from competing regional interests.

Fig. 9.15

The siege of Qandahar

9.1 The Safavids and Qandahar

The political and diplomatic relations between the Mughal kings and the neighbouring countries of Iran and Turan hinged on the control of the frontier defined by the Hindukush mountains that separated Afghanistan from the regions of Iran and Central Asia. All conquerors who sought to make their way into the Indian subcontinent had to cross the Hindukush to have access to north India. A constant aim of Mughal policy was to ward off this potential danger by controlling strategic outposts – notably Kabul and Qandahar.

Fig. 9.16

Jahangir’s dream

An inscription on this miniature records that Jahangir commissioned Abu’l Hasan to render in painting a dream the emperor had had recently. Abu’l Hasan painted this scene portraying the two rulers – Jahangir and the Safavid Shah Abbas – in friendly embrace. Both kings are depicted in their traditional costumes. The figure of the Shah is based upon portraits made by Bishandas who accompanied the Mughal embassy to Iran in 1613. This gave a sense of authenticity to a scene which is fictional, as the two rulers had never met.

Look at the painting carefully. How is the relationship between Jahangir and Shah Abbas shown? Compare their physique and postures. What do the animals stand for? What does the map suggest?

Qandahar was a bone of contention between the Safavids and the Mughals. The fortress-town had initially been in the possession of Humayun, reconquered in 1595 by Akbar. While the Safavid court retained diplomatic relations with the Mughals, it continued to stake claims to Qandahar. In 1613 Jahangir sent a diplomatic envoy to the court of Shah Abbas to plead the Mughal case for retaining Qandahar, but the mission failed. In the winter of 1622 a Persian army besieged Qandahar. The ill-prepared Mughal garrison was defeated and had to surrender the fortress and the city to the Safavids.

9.2 The Ottomans: pilgrimage and trade

The relationship between the Mughals and the Ottomans was marked by the concern to ensure free movement for merchants and pilgrims in the territories under Ottoman control. This was especially true for the Hijaz, that part of Ottoman Arabia where the important pilgrim centres of Mecca and Medina were located. The Mughal emperor usually combined religion and commerce by exporting valuable merchandise to Aden and Mokha, both Red Sea ports, and distributing the proceeds of the sales in charity to the keepers of shrines and religious men there. However, when Aurangzeb discovered cases of misappropriation of funds sent to Arabia, he favoured their distribution in India which, he thought, “was as much a house of God as Mecca”.

Source 4

The accessible emperor

In the account of his experiences, Monserrate, who was a member of the first Jesuit mission, says:

It is hard to exaggerate how accessible he (Akbar) makes himself to all who wish audience of him. For he creates an opportunity almost every day for any of the common people or of the nobles to see him and to converse with him; and he endeavours to show himself pleasant-spoken and affable rather than severe towards all who come to speak with him. It is very remarkable how great an effect this courtesy and affability has in attaching him to the minds of his subjects.

Compare this account with Source 2.

9.3 Jesuits at the Mughal court

Europe received knowledge of India through the accounts of Jesuit missionaries, travellers, merchants and diplomats. The Jesuit accounts are the earliest impressions of the Mughal court ever recorded by European writers.

Following the discovery of a direct sea route to India at the end of the fifteenth century, Portuguese merchants established a network of trading stations in coastal cities. The Portuguese king was also interested in the propagation of Christianity with the help of the missionaries of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits). The Christian missions to India during the sixteenth century were part of this process of trade and empire building.

Akbar was curious about Christianity and dispatched an embassy to Goa to invite Jesuit priests. The first Jesuit mission reached the Mughal court at Fatehpur Sikri in 1580 and stayed for about two years. The Jesuits spoke to Akbar about Christianity and debated its virtues with the ulama. Two more missions were sent to the Mughal court at Lahore, in 1591 and 1595.

The Jesuit accounts are based on personal observation and shed light on the character and mind of the emperor. At public assemblies the Jesuits were assigned places in close proximity to Akbar’s throne. They accompanied him on his campaigns, tutored his children, and were often companions of his leisure hours. The Jesuit accounts corroborate the information given in Persian chronicles about state officials and the general conditions of life in Mughal times.

Discuss...

What were the considerations that shaped the relations of the Mughal rulers with their contemporaries?

10. Questioning Formal Religion

The high respect shown by Akbar towards the members of the Jesuit mission impressed them deeply. They interpreted the emperor’s open interest in the doctrines of Christianity as a sign of his acceptance of their faith. This can be understood in the light of the prevailing climate of religious intolerance in Western Europe. Monserrate remarked that “the king cared little that in allowing everyone to follow his religion he was in reality violating all”.

Akbar’s quest for religious knowledge led to interfaith debates in the ibadat khana at Fatehpur Sikri between learned Muslims, Hindus, Jainas, Parsis and Christians. Akbar’s religious views matured as he queried scholars of different religions and sects and gathered knowledge about their doctrines. Increasingly, he moved away from the orthodox Islamic ways of understanding religions towards a self-conceived eclectic form of divine worship focused on light and the sun. We have seen that Akbar and Abu’l Fazl created a philosophy of light and used it to shape the image of the king and ideology of the state. In this, a divinely inspired individual has supreme sovereignty over his people and complete control over his enemies.

Fig. 9.17

Religious debates in the court

Padre Rudolf Acquaviva was the leader of the first Jesuit mission. His name is written on top of the painting.

Hom in the haram

This is an excerpt from Abdul Qadir Badauni’s Muntakhab-ut Tawarikh. A theologian and a courtier, Badauni was critical of his employer’s policies and did not wish to make the contents of his book public. From early youth, in compliment to his wives, the daughters of Rajas of Hind, His Majesty had been performing hom in the haram, which is a ceremony derived from fire-worship (atish-parasti). But on the New Year of the twenty-fifth regnal year (1578) he prostrated publicly before the sun and the fire. In the evening the whole Court had to rise up respectfully when the lamps and candles were lighted.

These ideas were in harmony with the perspective of the court chroniclers who give us a sense of the processes by which the Mughal rulers could effectively assimilate such a heterogeneous populace within an imperial edifice. The name of the dynasty continued to enjoy legitimacy in the subcontinent for a century and a half, even after its geographical extent and the political control it exercised had diminished considerably.

Fig. 9.18

Blue tiles from a shrine in Multan,

brought by migrant artisans

from Iran

Answer in100-150 words

1. Describe the process of manuscript production in the Mughal court.

2. In what ways would the daily routine and special festivities associated with the Mughal court have conveyed a sense of the power of the emperor?

3. Assess the role played by women of the imperial household in the Mughal Empire.

4. What were the concerns that shaped Mughal policies and attitudes towards regions outside the subcontinent?

5. Discuss the major features of Mughal provincial administration. How did the centre control the provinces?

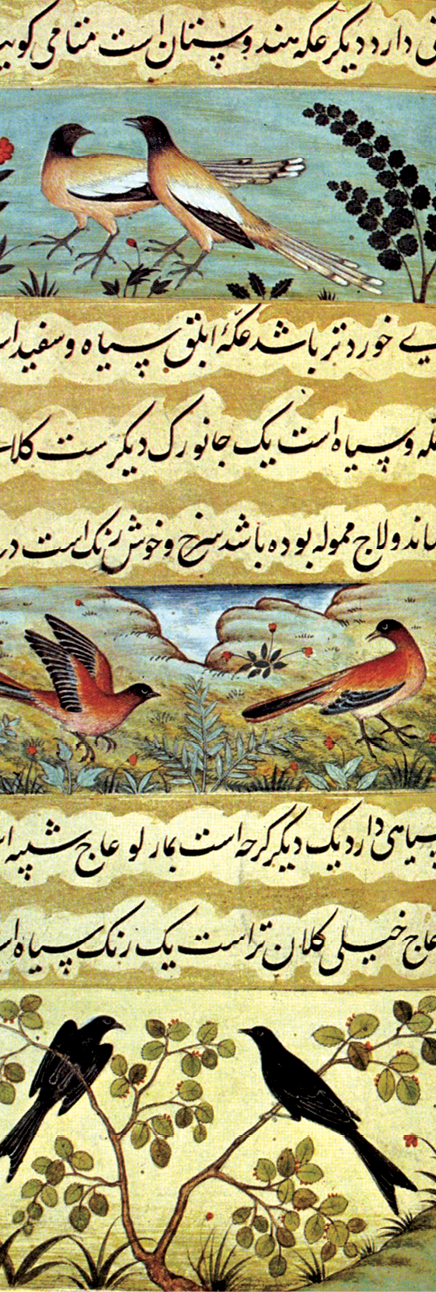

Fig. 9.19

Many Mughal manuscripts contained drawings of birds

Write a short essay (about 250-300 words) on the following:

6. Discuss, with examples, the distinctive features of Mughal chronicles.

7. To what extent do you think the visual material presented in this chapter corresponds with Abu’l Fazl’s description of the taswir (Source 1)?

8. What were the distinctive features of the Mughal nobility? How was their relationship with the emperor shaped?

9. Identify the elements that went into the making of the Mughal ideal of kingship.

Map work

10. On an outline map of the world, plot the areas with which the Mughals had political and cultural relations.

Project (choose one)

11. Find out more about any one Mughal chronicle. Prepare a report describing the author, and the language, style and content of the text. Describe at least two visuals used to illustrate the chronicle of your choice, focusing on the symbols used to indicate the power of the emperor.

12. Prepare a report comparing the present-day system of government with the Mughal court and administration, focusing on ideals of rulership, court rituals, and means of recruitment into the imperial service, highlighting the similarities and differences that you notice.

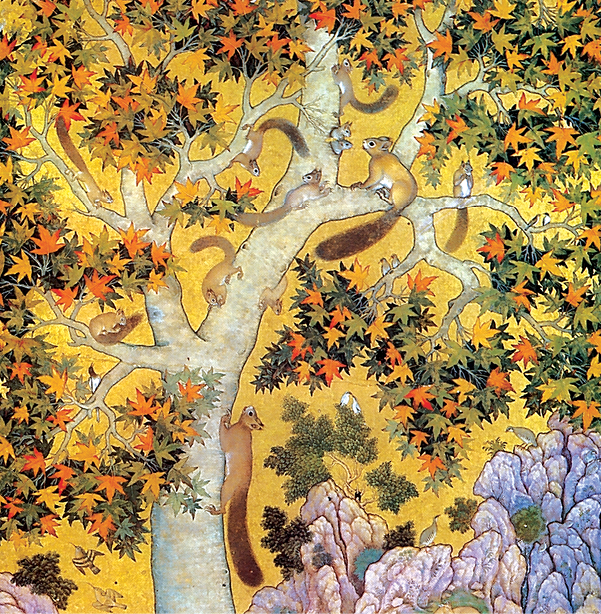

Fig. 9.20

A Mughal painting depicting squirrels on a tree

If you would like to know more, read:

Bamber Gascoigne. 1971.

The Great Moghuls.

Jonathan Cape Ltd., London.

Shireen Moosvi. 2006 (rpt).

Episodes in the Life of Akbar.

National Book Trust,

New Delhi.

Harbans Mukhia. 2004.

The Mughals of India. Blackwell, Oxford.

John F. Richards. 1996.

The Mughal Empire

(The New Cambridge History

of India, Vol.1).

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Annemarie Schimmel. 2005.

The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture.

Oxford University Press,

New Delhi.

For more information, you could visit:

www.mughalgardens.org

Credits for Illustrations

Theme 5

Fig. 5.1: Ritu Topa.

Fig. 5.2: Henri Stierlin, The Cultural History of the Arabs, Aurum Press, London, 1981.

Fig. 5.4, 5.13: FICCI, Footprints of Enterprise: Indian Business Through the Ages, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1999.

Fig. 5.5: Calcutta Art Gallery, printed in E.B. Havell,

The Art Heritage of India, D.B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay, 1964.

Fig. 5.6, 5.7, 5.12: Bamber Gascoigne, The Great Moghuls, Jonathan Cape Ltd., London, 1971.

Fig. 5.8, 5.9: Sunil Kumar.

Fig. 5.10: Rosemary Crill, Indian Ikat Textiles, Weatherhill, London, 1998.

Fig. 5.11, 5.14: C.A. Bayly (ed). An Illustrated History of Modern India, 1600-1947, Oxford University Press, Bombay, 1991.

Theme 6

Fig. 6.1: Susan L. Huntington, The Art of Ancient India, Weatherhill, New York, 1993.

Fig. 6.3, 6.17: Jim Masselos, Jackie Menzies and Pratapaditya Pal, Dancing to the Flute: Music and Dance in Indian Art, The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, 1997.

Fig. 6.4, 6.5: Benjamin Rowland, The Art and Architecture of India, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1970.

Fig. 6.6: Henri Stierlin, The Cultural History of the Arabs, Aurum Press, London, 1981.

Fig. 6.8: http://www.us.iis.ac.uk/view_article.asp/ContentID=104228

Fig. 6.9: http://www.thekkepuram.ourfamily.com/miskal.htm

Fig. 6.10: http://a-bangladesh.com/banglapedia/Images/A_0350A.JPG

Fig. 6.11: [email protected]

Fig. 6.12: Stuart Cary Welch, Indian Art and Culture 1300-1900, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1985.

Fig. 6.13: Bamber Gascoigne, The Great Moghuls, Jonathan Cape Ltd., London, 1971.

Fig. 6.15: CCRT.

Fig. 6.16: C. A. Bayly (ed). An Illustrated History of Modern India, 1600-1947, Oxford University Press, Bombay, 1991.

Fig. 6.18: Ahmad Nabi Khan, Islamic Architecture in Pakistan, National Hijra Council, Islamabad, 1990.

Theme 7

Fig. 7.1, 7.11, 7.12, 7.14, 7.15, 7.16, 7.18: Vasundhara Filliozat and George Michell (eds), The Splendours of Vijayanagara, Marg Publications, Bombay, 1981.

Fig. 7.2: C.A. Bayly (ed). An Illustrated History of Modern India, 1600-1947, Oxford University Press, Bombay, 1991.

Fig. 7.3: Susan L. Huntington, The Art of Ancient India, Weatherhill, New York, 1993.

Fig. 7.4, 7.6, 7.7, 7.20, 7. 23, 7.26, 7.27, 7.32: George Michell, Architecture and Art of South India, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995.

Fig. 7.5, 7.8, 7.9, 7.21 http://www.museum.upenn.edu/new/ research/Exp_Rese_Disc/Asia/vrp/HTML/Vijay_Hist.shtml

Fig 7.10: Catherine B. Asher and Cynthia Talbot. India Before Europe, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006.

Fig. 7.17, 7.22, 7.24, 7.28, 7.29, 7.30, 7.31, 7.33: George Michell and M.B.Wagoner, Vijayanagara: Architectural Inventory of the Sacred Centre, Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi.

Fig. 7.25: CCRT.

Theme 8

Fig. 8.1, 8.9: Milo Cleveland Beach and Ebba Koch, King of the World, Sackler Gallery, New York, 1997.

Fig. 8.3: India Office Library, printed in C.A. Bailey (ed). An Illustrated History of Modern India, 1600-1947, Oxford University Press, Bombay, 1991.

Fig. 8.4: Harvard University Art Museum, printed in Stuart Cary Welch, Indian Art and Culture 1300-1900, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1985.

Fig. 8.6, 8.11, 8.12, 8.14: C.A. Bayly (ed). An Illustrated History of Modern India, 1600-1947, Oxford University Press, Bombay, 1991.

Fig. 8.13, 8.15: Bamber Gascoigne, The Great Moghuls, Jonathan Cape Ltd., London, 1971.

Theme 9

Fig. 9.1, 9.2, 9.12, 9.13, 9.19: Bamber Gascoigne, The Great Moghuls,Jonathan Cape, London, 1971.

Fig. 9.3, 9.4, 9.17: Michael Brand and Glenn D. Lowry, Akbar’s India, New York, 1986.

Fig. 9.5, 9.15: Amina Okada, Indian Miniatures of the Mughal Court.

Fig. 9.6, 9.7: The Jahangirnama (tr. Wheeler Thackston)

Fig. 9.8: Photograph Friedrich Huneke.

Fig. 9.9, 9.11 a, b, c : Milo Cleveland Beach and Ebba Koch, King of the World, Sackler Gallery, New York, 1997.

Fig. 9.10, 9.16, 9.20: Stuart Carey Welch, Imperial Mughal Painting, George Braziller, New York, 1978.

Fig. 9.14: Geeti Sen, Paintings from the Akbarnama.

Fig. 9.18: Hermann Forkl et al. (eds), Die Gärten des Islam.