Table of Contents

Stamps like these, issued mostly between 1955 and 1968, depicted a vision of planned development. Left to right, top to bottom: Damodar Valley, Bhakra Dam, Chittaranjan Locomotives, Gauhati Refinery, Tractor, Sindri Fertilisers, Bhakra Dam, Electric Train, Wheat Revolution, Hirakud Dam, Hindustan Aircraft Factory

In this chapter…

In the last two chapters we have studied how the leaders of independent India responded to the challenges of nation-building and establishing democracy. Let us now turn to the third challenge, that of economic development to ensure well-being of all. As in the case of the first two challenges, our leaders chose a path that was different and difficult. In this case their success was much more limited, for this challenge was tougher and more enduring.

In this chapter, we study the story of political choices involved in some of the key questions of economic development.

- What were the key choices and debates about development?

- Which strategy was adopted by our leaders in the first two decades? And why?

- What were the main achievements and limitations of this strategy?

- Why was this development strategy abandoned in later years?

CHAPTER 3

POLITICS OF PLANNED DEVELOPMENT

As the global demand for steel increases, Orissa, which has one of the largest reserves of untapped iron ore in the country, is being seen as an important investment destination. The State government hopes to cash in on this unprecedented demand for iron ore and has signed Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with both international and domestic steel makers. The government believes that this would bring in necessary capital investment and proivde a lot of employment opportunities. The iron ore resources lie in some of the most underdeveloped and predominantly tribal districts of the state. The tribal population fears that the setting up of industries would mean displacement from their home and livelihood. The environmentalists fear that mining and industry would pollute the environment. The central government feels that if the industry is not allowed it would set a bad example and discourage investments in the country.

Orissa villagers protest against POSCO plant

Staff Reporter

BHUBANESWAR: People facing displacement by the proposed POSCO-India steel plant in Jagatsinghpur district staged a demonstration outside the Korean company’s office here on Thursday. They were demanding cancellation of the memorandum of understanding signed between the company and the Orissa government one year ago.

More than 100 men and women from the gram panchayats of Dhinkia, Nuagaon and Gadakujanga tried to enter the office premises but the police prevented them. Raising slogans, the protesters said the company should not be allowed to set up its plant at the cost of their lives and livelihood. The demonstration was organised by the Rashtriya Yuva Sangathan and the Nabanirman Samiti.

The Hindu, 23 June 2006

Can you identify the various interests involved in this case? What are their key points of conflict? Do you think there are any common points on which everyone can agree? Can this issue be resolved in a way which satisfies all the various interests? As you ask these questions, you would find yourself facing yet bigger questions. What kind of development does Orissa need? Indeed, whose need can be called Orissa’s need?

Political contestation

These questions cannot be answered by an expert. Decisions of this kind involve weighing the interests of one social group against another, present generation against future generations. In a democracy such major decisions should be taken or at least approved by the people themselves. It is important to take advice from experts on mining, from environmentalists and from economists. Yet the final decision must be a political decision, taken by people’s representatives who are in touch with the feelings of the people.

After independence our country had to make a series of major decisions like this. Each of these decisions could not be made independent of other such decisions. All these decisions were bound together by a shared vision or model of economic development. Almost everyone agreed that the development of India should mean both economic growth and social and economic justice. It was also agreed that this matter cannot be left to businessmen, industrialists and farmers themselves, that the government should play a key role in this. There was disagreement, however, on the kind of role that the government must play in ensuring growth with justice. Was it necessary to have a centralised institution to plan for the entire country? Should the government itself run some key industries and business? How much importance was to be attached to the needs of justice if it differed from the requirements of economic growth?

What is Left and what is Right?

In the politics of most countries, you will always come across references to parties and groups

with a left or right ideology or leaning. These terms characterise the position of the concerned groups or parties regarding social change and role of the state in effecting economic redistribution. Left often refers to those who are in favour of the poor, downtrodden sections and support government policies for the benefit of these sections. The Right refers to those who believe that free competition and market economy alone ensure progress and that the government should not unnecessarily intervene in the economy.

Can you tell which of the parties in the 1960s were Rightist and which were the Left parties? Where would you place the Congress party of that time?

Each of these questions involved contestation which has continued ever since. Each of the decision had political consequence. Most of these issues involved political judgement and required consultations among political parties and approval of the public. That is why we need to study the process of development as a part of the history of politics in India.

Ideas of development

Very often this contestation involves the very idea of development. The example of Orissa shows us that it is not enough to say that everyone wants development. For ‘development’ has different meanings for different sections of the people. Development would mean different things for example, to an industrialist who is planning to set up a steel plant, to an urban consumer of steel and to the Adivasi who lives in that region. Thus any discussion on development is bound to generate contradictions, conflicts and debates.

The first decade after independence witnessed a lot of debate around this question. It was common then, as it is even now, for people to refer to the ‘West’ as the standard for measuring development. ‘Development’ was about becoming more ‘modern’ and modern was about becoming more like the industrialised countries of the West. This is how common people as well as the experts thought. It was believed that every country would go through the process of modernisation as in the West, which involved the breakdown of traditional social structures and the rise of capitalism and liberalism. Modernisation was also associated with the ideas of growth, material progress and scientific rationality. This kind of idea of development allowed everyone to talk about different countries as developed, developing or underdeveloped.

On the eve of independence, India had before it, two models of modern development: the liberal-capitalist model as in much of Europe and the US and the socialist model as in the USSR. You have already studied these two ideologies and read about the ‘cold war’ between the two super powers. There were many in India then who were deeply impressed by the Soviet model of development. These included not just the leaders of the Communist Party of India, but also those of the Socialist Party and leaders like Nehru within the Congress. There were very few supporters of the American style capitalist development.

This reflected a broad consensus that had developed during the national movement. The nationalist leaders were clear that the economic concerns of the government of free India would have to be different from the narrowly defined commercial functions of the colonial government. It was clear, moreover, that the task of poverty alleviation and social and economic redistribution was being seen primarily as the responsibility of the government. There were debates among them. For some, industrialisation seemed to be the preferred path. For others, the development of agriculture and in particular alleviation of rural poverty was the priority.

Planning

Despite the various differences, there was a consensus on one point: that development could not be left to private actors, that there was the need for the government to develop a design or plan for development. In fact the idea of planning as a process of rebuilding economy earned a good deal of public support in the 1940s and 1950s all over the world. The experience of Great Depression in Europe, the inter-war reconstruction of Japan and Germany, and most of all the spectacular economic growth against heavy odds in the Soviet Union in the 1930s and 1940s contributed to this consensus.

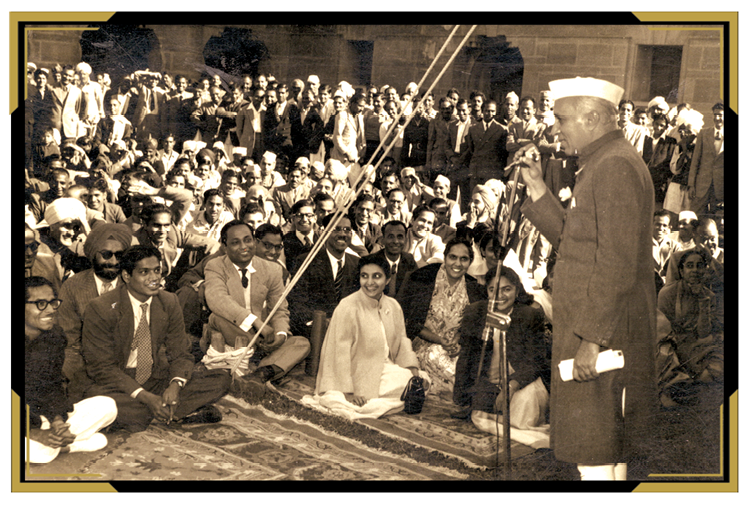

Credit: Hindustan Times

Nehru addressing the staff of the planning commission

Fast Forward Niti Aayog

Thus the Planning Commission was not a sudden invention. In fact, it has a very interesting history. We commonly assume that private investors, such as industrialists and big business entrepreneurs, are averse to ideas of planning: they seek an open economy without any state control in the flow of capital. That was not what happened here. Rather, a section of the big industrialists got together in 1944 and drafted a joint proposal for setting up a planned economy in the country. It was called the Bombay Plan. The Bombay Plan wanted the state to take major initiatives in industrial and other economic investments. Thus, from left to right, planning for development was the most obvious choice for the country after independence. Soon after India became independent, the Planning Commission came into being. The Prime Minister was its Chairperson. It became the most influential and central machinery for deciding what path and strategy India would adopt for its development.

The Early Initiatives

As in the USSR, the Planning Commission of India opted for five year plans (FYP). The idea is very simple: the government of India prepares a document that has a plan for all its income and expenditure for the next five years. Accordingly the budget of the central and all the State governments is divided into two parts: ‘non-plan’ budget that is spent on routine items on a yearly basis and ‘plan’ budget that is spent on a five year basis as per the priorities fixed by the plan. A five year plan has the advantage of permitting the government to focus on the larger picture and make long-term intervention in the economy.

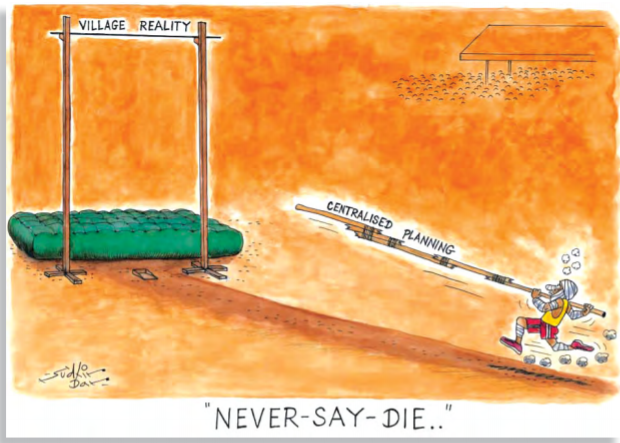

Credit: Sudhir Dar/UNDP and Planning Commission

The draft of the First Five Year Plan and then the actual Plan Document, released in December 1951, generated a lot of excitement in the country. People from all walks of life – academics, journalists, government and private sector employees, industrialists, farmers, politicians etc. – discussed and debated the documents extensively. The excitement with planning reached its peak with the launching of the Second Five Year Plan in 1956 and continued somewhat till the Third Five Year Plan in 1961. The Fourth Plan was due to start in 1966. By this time, the novelty of planning had declined considerably, and moreover, India was facing acute economic crisis. The government decided to take a ‘plan holiday’. Though many criticisms emerged both about the process and the priorities of these plans, the foundation of India’s economic development was firmly in place by then.

The First Five Year Plan

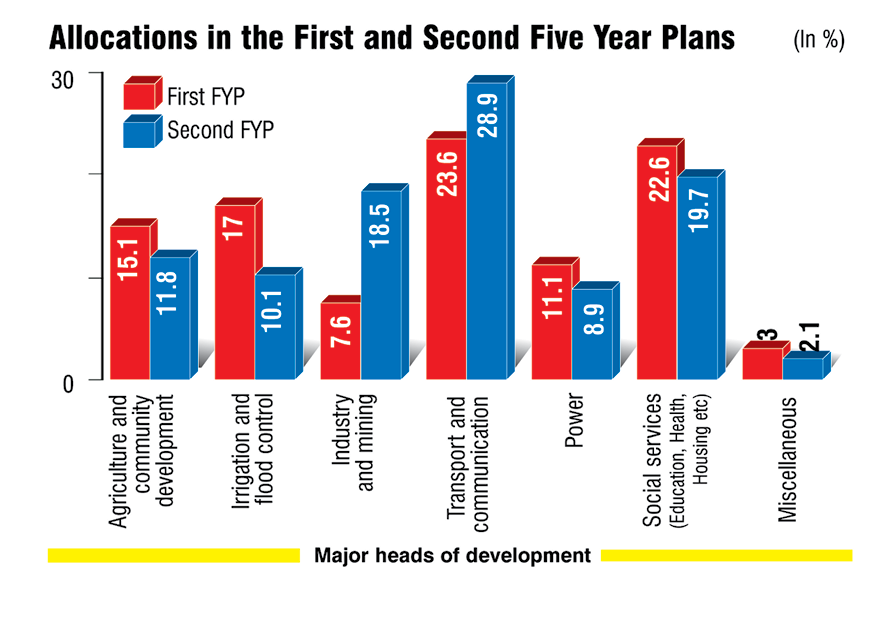

The First Five Year Plan (1951–1956) sought to get the country’s economy out of the cycle of poverty. K.N. Raj, a young economist involved in drafting the plan, argued that India should ‘hasten slowly’ for the first two decades as a fast rate of development might endanger democracy. The First Five Year Plan addressed, mainly, the agrarian sector including investment in dams and irrigation. Agricultural sector was hit hardest by partition and needed urgent attention. Huge allocations were made for large-scale projects like the Bhakhra Nangal Dam. The Plan identified the pattern of land distribution in the country as the principal obstacle in the way of agricultural growth. It focused on land reforms as the key to the country’s development.

Tenth Five Year Plan document

One of the basic aims of the planners was to raise the level of national income, which could be possible only if the people saved more money than they spent. As the basic level of spending was very low in the 1950s, it could not be reduced any more. So the planners sought to push savings up. That too was difficult as the total capital stock in the country was rather low compared to the total number of employable people. Nevertheless, people’s savings did rise in the first phase of the planned process until the end of the Third Five Year Plan. But, the rise was not as spectacular as was expected at the beginning of the First Plan. Later, from the early 1960s till the early 1970s, the proportion of savings in the country actually dropped consistently.

Rapid Industrialisation

The Second FYP stressed on heavy industries. It was drafted by a team of economists and planners under the leadership of P. C. Mahalanobis. If the first plan had preached patience, the second wanted to bring about quick structural transformation by making changes simultaneously in all possible directions. Before this plan was finalised, the Congress party at its session held at Avadi near the then Madras city, passed an important resolution. It declared that ‘socialist pattern of society’ was its goal. This was reflected in the second plan. The government imposed substantial tariffs on imports in order to protect domestic industries. Such protected environment helped both public and private sector industries to grow. As savings and investment were growing in this period, a bulk of these industries like electricity, railways, steel, machineries and communication could be developed in the public sector. Indeed, such a push for industrialisation marked a turning point in India’s development.

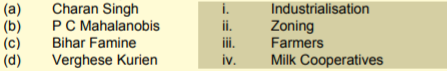

P.C. Mahalanobis (1893-1972): Scientist and statistician of international repute; founder of Indian Statistical Institute (1931); architect of the second plan; supporter of rapid industrialisation and active role of the public sector.

It, however, had its problems as well. India was technologically backward, so it had to spend precious foreign exchange to buy technology from the global market. That apart, as industry attracted more investment than agriculture, the possibility of food shortage loomed large. The Indian planners found balancing industry and agriculture really difficult. The Third Plan was not significantly different from the Second. Critics pointed out that the plan strategies from this time around displayed an unmistakable “urban bias”. Others thought that industry was wrongly given priority over agriculture. There were also those who wanted focus on agriculture-related industries rather than heavy ones.

Decentralised planning

It is not necessary that all planning always has to be centralised; nor is it that planning is only about big industries and large projects. The ‘Kerala model’ is the name given to the path of planning and development charted by the State of Kerala. There has been a focus in this model on education, health, land reform, effective food distribution, and poverty alleviation. Despite low per capita incomes, and a relatively weak industrial base, Kerala achieved nearly total literacy, long life expectancy, low infant and female mortality, low birth rates and high access to medical care. Between 1987 and 1991, the government launched the New Democratic Initiative which involved campaigns for development (including total literacy especially in science and environment) designed to involve people directly in development activities through voluntary citizens’ organisations. The State has also taken initiative to involve people in making plans at the Panchayat, block and district level.

Key Controversies

The strategy of development followed in the early years raised several important questions. Let us examine two of these disputes that continue to be relevant.

Agriculture versus industry

We have already touched upon a big question: between agriculture and industry, which one should attract more public resources in a backward economy like that of India? Many thought that the Second Plan lacked an agrarian strategy for development, and the emphasis on industry caused agriculture and rural India to suffer. Gandhian economists like J. C. Kumarappa proposed an alternative blueprint that put greater emphasis on rural industrialisation. Chaudhary Charan Singh, a Congress leader who later broke from the party to form Bharatiya Lok Dal, forcefully articulated the case for keeping agriculture at the centre of planning for India. He said that the planning was leading to creation of prosperity in urban and industrial section at the expense of the farmers and rural population.

J.C. Kumarappa (1892-1960): Original name J.C. Cornelius; economist and chartered accountant; studied in England and USA; follower of Mahatma Gandhi; tried to apply Gandhian principles to economic policies; author of ‘Economy of Permanence’; participated in planning process as member of the planning Commission

Let’s watch a Film

Pather Panchali

This film tells the story of a poor family in a Bengal village and its struggle to survive. Durga, the daughter of Harihar and Sarbajaya, with her younger brother, Apu, goes on enjoying life oblivious of the struggles and the poverty. The film revolves around the simple life and the efforts of the mother of Durga and Apu to maintain

the family.

Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road) narrates the desires and disappointments of the poor family through the tale of the youngsters. Finally, during monsoon, Durga falls ill and dies while her father is away. Harihar returns with gifts, including a sari for Durga…..

The film won numerous awards nationally and internationally, including the President’s Gold and Silver medals for the year 1955.

Year: 1955

Director: Satyajit Ray

Story: Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay

Screenplay: Satyajit Ray

Actors: Kanu Bannerjee, Karuna Bannerjee, Subir Bannerjee, Uma Das Gupta Durga, Chunibala Devi

Others thought that without a drastic increase in industrial production, there could be no escape from the cycle of poverty. They argued that Indian planning did have an agrarian strategy to boost the production of food-grains. The state made laws for land reforms and distribution of resources among the poor in the villages. It also proposed progra-mmes of community development and spent large sums on irrigation projects. The failure was not that of policy but its non-implementation, because the landowning classes had lot of social and political power. Besides, they also argue that even if the government had spent more money on agriculture it would not have solved the massive problem of rural poverty.

Public versus private sector

India did not follow any of the two known paths to development – it did not accept the capitalist model of development in which development was left entirely to the private sector, nor did it follow the socialist model in which private property was abolished and all the production was controlled by the state. Elements from both these models were taken and mixed together in India. That is why it was described as ‘mixed economy’. Much of the agriculture, trade and industry were left in private hands. The state controlled key heavy industries, provided industrial infrastructure, regulated trade and made some crucial interventions in agriculture.

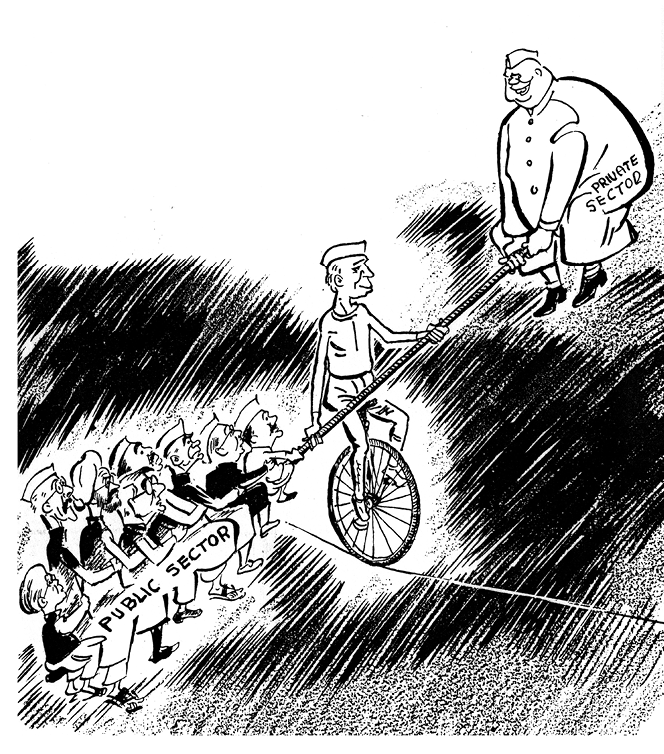

A mixed model like this was open to criticism from both the left and the right. Critics argued that the planners refused to provide the private sector with enough space and the stimulus to grow. The enlarged public sector produced powerful vested interests that created enough hurdles for private capital, especially by way of installing systems of licenses and permits for investment. Moreover, the state’s policy to restrict import of goods that could be produced in the domestic market with little or no competition left the private sector with no incentive to improve their products and make them cheaper. The state controlled more things than were necessary and this led to inefficiency and corruption.

Credit: Shankar, 6 May 1956

Astride the Public Sector are Central Ministers Lal Bahadur Shastri, Ajit Prasad Jain, Kailash Nath Katju, Jagjivan Ram, T. T. Krishnamachari, Swaran Singh, Gulzari Lal Nanda and B. V. Keskar

Then there were critics who thought that the state did not do enough. They pointed out that the state did not spend any significant amount for public education and healthcare. The state intervened only in those areas where the private sector was not prepared to go. Thus the state helped the private sector to make profit. Also, instead of helping the poor, the state intervention ended up creating a new ‘middle class’ that enjoyed the privileges of high salaries without much accountability. Poverty did not decline substantially during this period; even when the proportion of the poor reduced, their numbers kept going up.

Major Outcomes

Of the three objectives that were identified in independent India, discussed in the first three chapters here, the third objective proved most difficult to realise. Land reforms did not take place effectively in most parts of the country; political power remained in the hands of the landowning classes; and big industrialists continued to benefit and thrive while poverty did not reduce much. The early initiatives for planned development were at best realising the goals of economic development of the country and well-being of all its citizens. The inability to take significant steps in this direction in the very first stage was to become a political problem. Those who benefited from unequal development soon became politically powerful and made it even more difficult to move in the desired direction.

Foundations

An assessment of the outcomes of this early phase of planned development must begin by acknowledging the fact that in this period the foundations of India’s future economic growth were laid. Some of the largest developmental projects in India’s history were undertaken during this period. These included mega-dams like Bhakhra-Nangal and Hirakud for irrigation and power generation. Some of the heavy industries in the public sector – steel plants, oil refineries, manufacturing units, defense production etc. – were started during this period. Infrastructure for transport and communication was improved substantially. Of late, some of these mega projects have come in for a lot of criticism. Yet much of the later economic growth, including that by the private sector, may not have been possible in the absence of these foundations.

Government Campaign reaches the village

“In a way the advertisement stuck or written on walls gave an accurate introduction to the villager’s problems and how to solve them. For example, the problem was that India was a farming nation, but farmers refused to produce more grain out of sheer perversity. The solution was to give speeches to farmers and show them all sorts of attractive pictures. These advised them that if they didn’t want to grow more grain for themselves then they should do so for the nation. As a result the posters were stuck in various places to induce farmers to grow grain for the nation. The farmers were greatly influenced by the combined effect of the speeches and posters, and even most simple-minded cultivator began to feel the likelihood of there was some ulterior motive behind the whole campaign.

One advertisement had become especially well known in Shivpalganj. It showed a healthy farmer with turban wrapped around his head, earrings and a quilted jacket, cutting a tall crop of wheat with a sickle. A woman was standing behind him, very pleased with herself; she was laughing like an official from the Department of Agriculture.

Below and above the picture was written in Hindi and English – ‘Grow More Grain’. Farmers with earrings and a quilted jacket who were also scholars of English were expected to be won over by the English slogans, and those who were scholars of Hindi, by the Hindi version. And those who didn’t know how to read either language could at least recognise the figures of the man and the laughing woman. The government hoped that as soon as they saw the man and the laughing woman, farmer would turn away from the poster and start growing more grain like men possessed”.

Extracts of translation from ‘Raag Darbari’ by Shrilal Shukla. The satire is set in a village Shivpalganj in Uttar Pradesh in the 1960s.

Land reforms

In the agrarian sector, this period witnessed a serious attempt at land reforms. Perhaps the most significant and successful of these was the abolition of the colonial system of zamindari. This bold act not only released land from the clutches of a class that had little interest in agriculture, it also reduced the capacity of the landlords to dominate politics. Attempts at consolidation of land – bringing small pieces of land together in one place so that the farm size could become viable for agriculture – were also fairly successful. But the other two components of land reforms were much less successful. Though the laws were made to put an upper limit or ‘ceiling’ to how much agricultural land one person could own, people with excess land managed to evade the law. Similarly, the tenants who worked on someone else’s land were given greater legal security against eviction, but this provision was rarely implemented.

Food Crisis

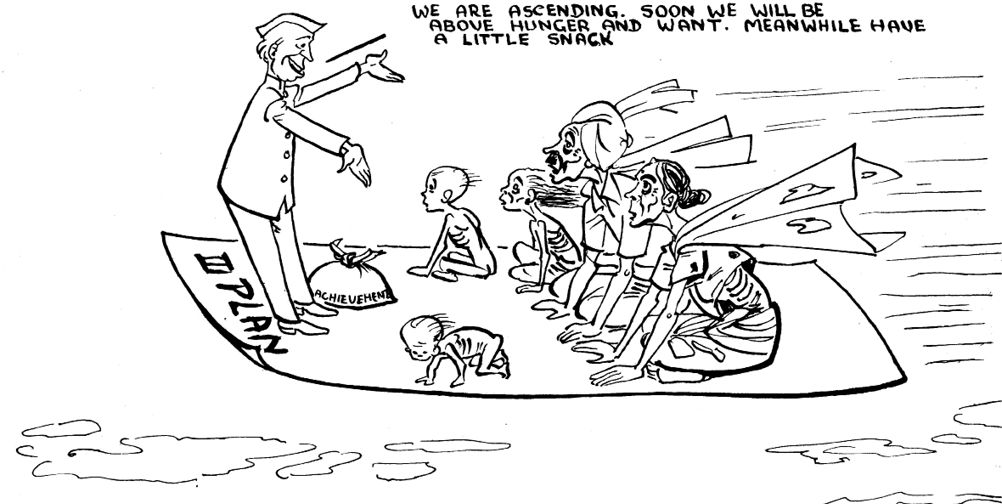

The agricultural situation went from bad to worse in the 1960s. Already, the rate of growth of food grain production in the 1940s and 1950s was barely staying above rate of population growth. Between 1965 and 1967, severe droughts occurred in many parts of the country. As we shall study in the next chapter, this was also the period when the country faced two wars and foreign exchange crisis. All this resulted in a severe food shortage and famine – like conditions in many parts of the country.

It was in Bihar that the food-crisis was most acutely felt as the state faced a near-famine situation. The food shortage was significant in all districts of Bihar, with 9 districts producing less than half of their normal output. Five of these districts, in fact, produced less than one-third of what they produced normally. Food deprivation subsequently led to acute and widespread malnutrition. It was estimated that the calorie intake dropped from 2200 per capita per day to as low as 1200 in many regions of the state (as against the requirement of 2450 per day for the average person). Death rate in Bihar in 1967 was 34% higher than the number of deaths that occurred in the following year. Food prices also hit a high in Bihar during the year, even when compared with other north Indian states. For wheat and rice the prices in the state were twice or more than their prices in more prosperous Punjab. The government had “zoning” policies that prohibited trade of food across states; this reduced the availability of food in Bihar dramatically. In situations such as this, the poorest sections of the society suffered the most.

The food crisis had many consequences. The government had to import wheat and had to accept foreign aid, mainly from the US. Now the first priority of the planners was to somehow attain self-sufficiency in food. The entire planning process and sense of optimism and pride associated with it suffered a setback.

It was not easy to turn these well-meaning policies on agriculture into genuine and effective action. This could happen only if the rural, landless poor were mobilised. But the landowners were very powerful and wielded considerable political influence. Therefore, many proposals for land reforms were either not translated into laws, or, when made into laws, they remained only on paper. This shows that economic policy is part of the actual political situation in the society. It also shows that in spite of good wishes of some top leaders, the dominant social groups would always effectively control policy making and implementation.

The Green Revolution

In the face of the prevailing food-crisis, the country was clearly vulnerable to external pressures and dependent on food aid, mainly from the United States. The United States, in turn, pushed India to change its economic policies. The government adopted a new strategy for agriculture in order to ensure food sufficiency. Instead of the earlier policy of giving more support to the areas and farmers that were lagging behind, now it was decided to put more resources into those areas which already had irrigation and those farmers who were already well-off. The argument was that those who already had the capacity could help increase production rapidly in the short run. Thus the government offered high-yielding variety seeds, fertilizers, pesticides and better irrigation at highly subsidised prices. The government also gave a guarantee to buy the produce of the farmers at a given price. This was the beginning of what was called the ‘green revolution’.

The rich peasants and the large landholders were the major beneficiaries of the process. The green revolution delivered only a moderate agricultural growth (mainly a rise in wheat production) and raised the availability of food in the country, but increased polarisation between classes and regions. Some regions like Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh became agriculturally prosperous, while others remained backward. The green revolution had two other effects: one was that in many parts, the stark contrast between the poor peasantry and the landlords produced conditions favourable for leftwing organisations to organise the poor peasants. Secondly, the green revolution also resulted in the rise of what is called the middle peasant sections. These were farmers with medium size holdings, who benefited from the changes and soon emerged politically influential in many parts of the country.

Let’s re-search

Srikanth still remembers the struggle his elder brother had to undergo in order to get the monthly supply of ration for the ration shop. Their family was totally dependent on the supplies from the ration shop for rice, oil and kerosene. Many times, his brother would stand in the queue for an hour or so only to find out that the supply had ended and he would have to come later when fresh supply arrives. Find out from talking to elders in your family what is a ration card and ask your elders what, if any, items they buy from the ration shop. Visit a ration shop in the vicinity of your school or home and find out what is the difference in the prices of at least three commodities—wheat\rice, cooking oil, sugar—between the ration shop and the open market.

Fast Forward The White Revolution

You must be familiar with the jingle ‘utterly butterly delicious’ and the endearing figure of the little girl holding a buttered toast. Yes, the Amul advertisements! Did you know that behind Amul products lies a successful history of cooperative dairy farming in India. Verghese Kurien, nicknamed the ‘milkman of India’, played a crucial role in the story of Gujarat Cooperative Milk and Marketing Federation Ltd that launched Amul.

Based in Anand, a town in Gujarat, Amul is a dairy cooperative movement joined by about 2 and half million milk producers in Gujarat. The Amul pattern became a uniquely appropriate model for rural development and poverty alleviation, spurring what has come to be known as the White Revolution. In 1970 the rural development programme called Operation Flood was started. Operation Flood organised cooperatives of milk producers into a nationwide milk grid, with the purpose of increasing milk production, bringing the producer and consumer closer by eliminating middlemen, and assuring the producers a regular income throughout the year. Operation Flood was, however, not just a dairy programme. It saw dairying as a path to development, for generating employment and income for rural households and alleviating poverty. The number of members of the cooperative has continued to increase with the numbers of women members and Women’s Dairy Cooperative Societies also increasing significantly.

Later developments

The story of development in India took a significant turn from the end of 1960s. You will see in Chapter Five how after Nehru’s death the Congress system encountered difficulties. Indira Gandhi emerged as a popular leader. She decided to further strengthen the role of the state in controlling and directing the economy. The period from 1967 onwards witnessed many new restrictions on private industry. Fourteen private banks were nationalised. The government announced many pro-poor programmes. These changes were accompanied by an ideological tilt towards socialist policies. This emphasis generated heated debates within the country among political parties and also among experts.

However, the consensus for a state-led economic development did not last forever. Planning did continue, but its salience was significantly reduced. Between 1950 and 1980 the Indian economy grew at a sluggish per annum rate of 3 to 3.5%. In view of the prevailing inefficiency and corruption in some public sector enterprises and the not-so-positive role of the bureaucracy in economic development, the public opinion in the country lost the faith it initially placed in many of these institutions. Such lack of public faith led the policy makers to reduce the importance of the state in India’s economy from the 1980s onwards. We shall look at that part of the story towards the end of this book.

EXERCISES

1. Which of these statements about the Bombay Plan is incorrect?

(a) It was a blueprint for India’s economic future.

(b) It supported state-ownership of industry.

(c) It was made by some leading industrialists.

(d) It supported strongly the idea of planning.n

2. Which of the following ideas did not form part of the early phase of India’s development policy?

(a) Planning (c) Cooperative Farming

(b) Liberalisation (d) Self sufficiency

3. The idea of planning in India was drawn from

(a) the Bombay plan (c) Gandhian vision of society

(b) experiences of the Soviet bloc countries organisations (d) Demand by peasant

i. b and d only iii. a and b only

ii. d and c only iv. all the above

4. Match the following.

5. What were the major differences in the approach towards development at the time of Independence? Has the debate been resolved?

6. What was the major thrust of the First Five Year Plan? In which ways did the Second Plan differ from the first one?

7. What was the Green Revolution? Mention two positive and two negative consequences of the Green Revolution.

8. State the main arguments in the debate that ensued between industrialisation and agricultural development at the time of the second Five Year Plan.

9. “Indian policy makers made a mistake by emphasising the role of state in the economy. India could have developed much better if private sector was allowed a free play right from the beginning”. Give arguments for or against this proposition.

10. Read the following passage and answer the questions below:

“In the early years of Independence, two contradictory tendencies were already well advanced inside the Congress party. On the one hand, the national party executive endorsed socialist principles of state ownership, regulation and control over key sectors of the economy in order to improve productivity and at the same time curb economic concentration. On the other hand, the national Congress government pursued liberal economic policies and incentives to private investment that was justified in terms of the sole criterion of achieving maximum increase in production. “ — Francine Frankel

(a) What is the contradiction that the author is talking about? What would be the political implications of a contradiction like this?

(b) If the author is correct, why is it that the Congress was pursuing this policy? Was it related to the nature of the opposition parties?

(c) Was there also a contradiction between the central leadership of the Congress party and its Sate level leaders?