Table of Contents

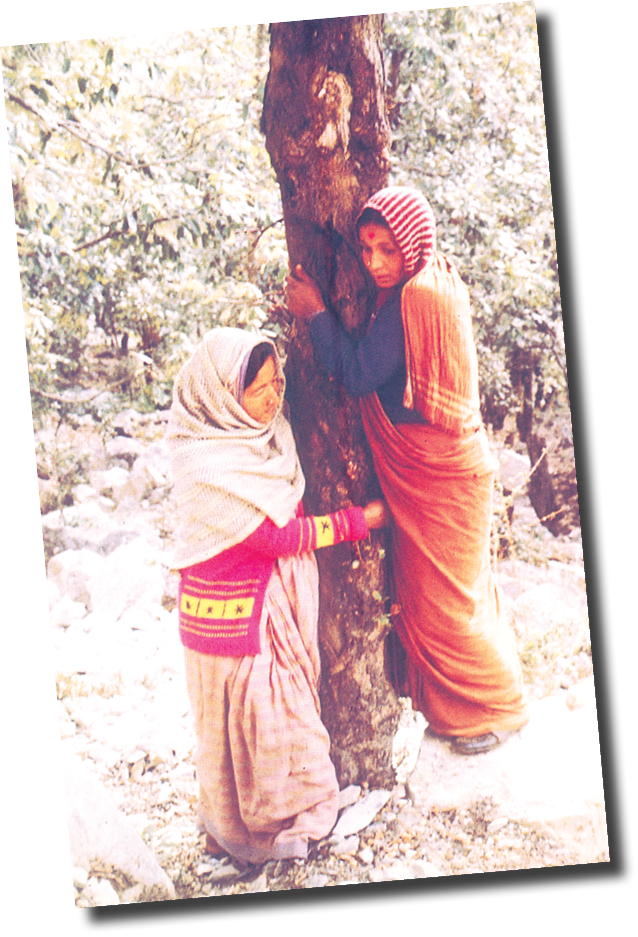

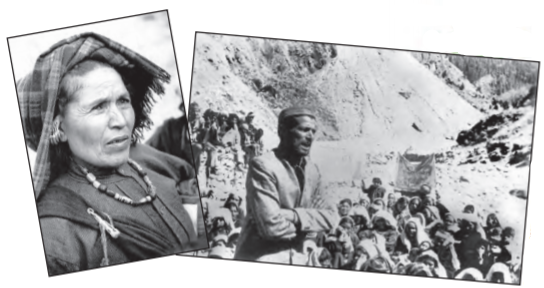

Photograph on this and the facing page are of the participants and leaders of the Chipko Movement, recognised as one of the first environmental movements in the country.

In this chapter…

Three decades after independence, the people were beginning to get impatient. Their unease expressed itself in various forms. In the previous chapter, we have already gone through the story of electoral upheavals and political crisis. Yet that was not the only form in which popular discontent expressed itself. In the 1970s, diverse social groups like women, students, Dalits and farmers felt that democratic politics did not address their needs and demands. Therefore, they came together under the banner of various social organisations to voice their demands. These assertions marked the rise of popular movements or new social movements in Indian politics.

In this chapter we trace the journey of some of the popular movements that developed after the 1970s in order to understand:

- what are popular movements?

- which sections of Indian society have they mobilised?

- what is the main agenda of these movements?

- what role do they play in a democratic set up like ours?

CHAPTER 7

RISE OF POPULAR MOVEMENTS

Nature of popular movements

Take a look at the opening image of this chapter. What do you see there? Villagers have literally embraced the trees. Are they playing some game? Or participating in some ritual or festival? Not really. The image here depicts a very unusual form of collective action in which men and women from a village in what is now Uttarakhand were engaged in early 1973. These villagers were protesting against the practices of commercial logging that the government had permitted. They used a novel tactic for their protest – that of hugging the trees to prevent them from being cut down. These protests marked the beginning of a world-famous environmental movement in our country – the Chipko movement.

Chipko movement

The movement began in two or three villages of Uttarakhand when the forest department refused permission to the villagers to fell ash trees for making agricultural tools. However, the forest department allotted the same patch of land to a sports manufacturer for commercial use. This enraged the villagers and they protested against the move of the government. The struggle soon spread across many parts of the Uttarakhand region. Larger issues of ecological and economic exploitation of the region were raised. The villagers demanded that no forest-exploiting contracts should be given to outsiders and local communities should have effective control over natural resources like land, water and forests. They wanted the government to provide low cost materials to small industries and ensure development of the region without disturbing the ecological balance. The movement took up economic issues of landless forest workers and asked for guarantees of minimum wage.

Two historic pictures of the early Chipko movement in Chamoli, Uttarakhand.

Women’s active participation in the Chipko agitation was a very novel aspect of the movement. The forest contractors of the region usually doubled up as suppliers of alcohol to men. Women held sustained agitations against the habit of alcoholism and broadened the agenda of the movement to cover other social issues. The movement achieved a victory when the government issued a ban on felling of trees in the Himalayan regions for fifteen years, until the green cover was fully restored. But more than that, the Chipko movement, which started over a single issue, became a symbol of many such popular movements emerging in different parts of the country during the 1970s and later. In this chapter we shall study some of these movements.

Party based movements

Popular movements may take the form of social movements or political movements and there is often an overlap between the two. The nationalist movement, for example, was mainly a political movement. But we also know that deliberations on social and economic issues during the colonial period gave rise to independent social movements like the anti-caste movement, the kisan sabhas and the trade union movement in early twentieth century. These movements raised issues related to some underlying social conflicts.

Some of these movements continued in the post-independence period as well. Trade union movement had a strong presence among industrial workers in major cities like Mumbai, Kolkata and Kanpur. All major political parties established their own trade unions for mobilising these sections of workers. Peasants in the Telangana region of Andhra Pradesh organised massive agitations under the leadership of Communist parties in the early years of independence and demanded redistribution of land to cultivators. Peasants and agricultural labourers in parts of Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, Bihar and adjoining areas continued their agitations under the leadership of the Marxist-Leninist workers; who were known as the Naxalites (you have already read about the Naxalite movement in the last chapter). The peasants’ and the workers’ movements mainly focussed on issues of economic injustice and inequality.

Some of these movements continued in the post-independence period as well. Trade union movement had a strong presence among industrial workers in major cities like Mumbai, Kolkata and Kanpur. All major political parties established their own trade unions for mobilising these sections of workers. Peasants in the Telangana region of Andhra Pradesh organised massive agitations under the leadership of Communist parties in the early years of independence and demanded redistribution of land to cultivators. Peasants and agricultural labourers in parts of Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, Bihar and adjoining areas continued their agitations under the leadership of the Marxist-Leninist workers; who were known as the Naxalites (you have already read about the Naxalite movement in the last chapter). The peasants’ and the workers’ movements mainly focussed on issues of economic injustice and inequality. These movements did not participate in elections formally. And yet they retained connections with political parties, as many participants in these movements, as individuals and as organisations, were actively associated with parties. These links ensured a better representation of the demands of diverse social sections in party politics.

Non-party movements

In the 1970s and 1980s, many sections of the society became disillusioned with the functioning of political parties. Failure of the Janata experiment and the resulting political instability were the immediate causes. But in the long run the disillusionment was also about economic policies of the state. The model of planned development that we adopted after independence was based on twin goals of growth and distribution. You have read about it in chapter three. In spite of the impressive growth in many sectors of economy in the first twenty years of independence, poverty and inequalities persisted on a large scale. Benefits of economic growth did not reach evenly to all sections of society. Existing social inequalities like caste and gender sharpened and complicated the issues of poverty in many ways. There also existed a gulf between the urban-industrial sector and the rural agrarian sector. A sense of injustice and deprivation grew among different groups.

Many of the politically active groups lost faith in existing democratic institutions and electoral politics. They therefore chose to step outside of party politics and engage in mass mobilisation for registering their protests. Students and young political activists from various sections of the society were in the forefront in organising the marginalised sections such as Dalits and Adivasis. The middle class young activists launched service organisations and constructive programmes among rural poor. Because of the voluntary nature of their social work, many of these organisations came to be known as voluntary organisations or voluntary sector organisations.

These voluntary organisations chose to remain outside party politics. They did not contest elections at the local or regional level nor did they support any one political party. Most of these groups believed in politics and wanted to participate in it, but not through political parties. Hence, these organisations were called ‘non-party political formations’. They hoped that direct and active participation by local groups of citizens would be more effective in resolving local issues than political parties. It was also hoped that direct participation by people will reform the nature of democratic government.

Such voluntary sector organisations still continue their work in rural and urban areas. However, their nature has changed. Of late many of these organisations are funded by external agencies including international service agencies. The ideal of local initiatives is weakened as a result of availability of external funds on a large scale to these organisations.

Namdeo Dhasal

Turning their backs to the sun, they journeyed through centuries.

Now, now we must refuse to be pilgrims of darkness.

That one, our father, carrying, carrying the darkness is now bent;

Now, now we must lift the burden from his back.

Our blood was spilled for this glorious city

And what we got was the right to eat stones

Now, now we must explode the building that kisses the sky!

After a thousand years we were blessed with sunflower giving fakir;

Now, now, we must like sunflowers turn our faces to the sun.

English translation by Jayant Karve and Eleanor Zelliot of Namdeo Dhasal’s Marathi poem in Golpitha.

Dalit Panthers

Read this poem by well-known Marathi poet Namdeo Dhasal. Do you know who these ‘pilgrims of darkness’ in this poem are and who the ‘sunflower-giving fakir’ was that blessed them? The pilgrims were the Dalit communities who had experienced brutal caste injustices for a long time in our society and the poet is referring to Dr. Ambedkar as their liberator. Dalit poets in Maharashtra wrote many such poems during the decade of seventies. These poems were expressions of anguish that the Dalit masses continued to face even after twenty years of independence. But they were also full of hope for the future, a future that Dalit groups wished to shape for themselves. You are aware of Dr. Ambedkar’s vision of socio-economic change and his relentless struggle for a dignified future for Dalits outside the Hindu caste-based social structure. It is not surprising that Dr. Ambedkar remains an iconic and inspirational figure in much of Dalit liberation writings.

Origins

By the early nineteen seventies, the first generation Dalit graduates, especially those living in city slums began to assert themselves from various platforms. Dalit Panthers, a militant organisation of the Dalit youth, was formed in Maharashtra in 1972 as a part of these assertions. In the post-independence period, Dalit groups were mainly fighting against the perpetual caste based inequalities and material injustices that the Dalits faced in spite of constitutional guarantees of equality and justice. Effective implementation of reservations and other such policies of social justice was one of their prominent demands.

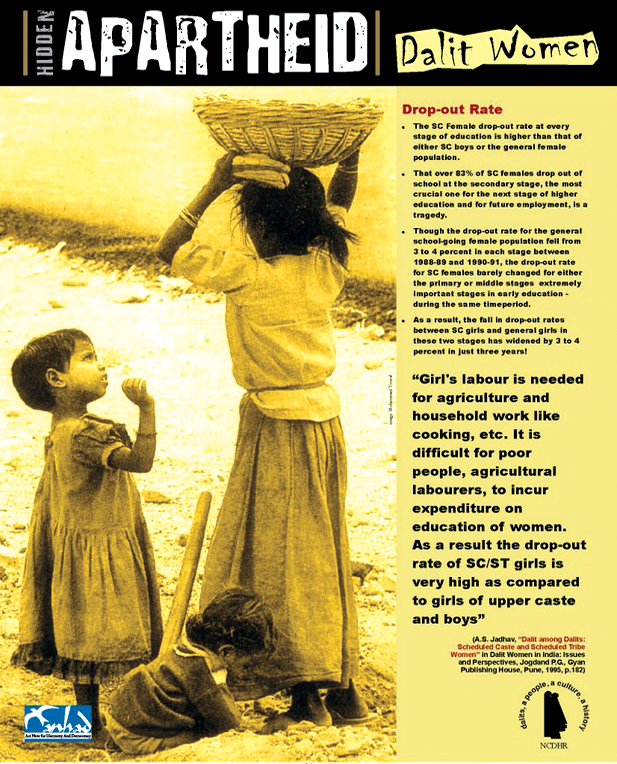

‘Apartheid’, meaning ‘separateness’, refers to the official policy of racial discrimination which existed in South Africa during the 20th century. Why is it called Hidden Apartheid here? Are there other examples of this?

You know that the Indian Constitution abolished the practice of untouchability. The government passed laws to that effect in the 1960s and 1970s. And yet, social discrimination and violence against the ex-untouchable groups continued in various ways. Dalit settlements in villages continued to be set apart from the main village. They were denied access to common source of drinking water. Dalit women were dishonoured and abused and worst of all, Dalits faced collective atrocities over minor, symbolic issues of caste pride. Legal mechanisms proved inadequate to stop the economic and social oppression of Dalits. On the other hand, political parties supported by the Dalits, like the Republican Party of India, were not successful in electoral politics. These parties always remained marginal; had to ally with some other party in order to win elections and faced constant splits. Therefore the Dalit Panthers resorted to mass action for assertion of Dalits’ rights.

Activities

Activities of Dalit Panthers mostly centred around fighting increasing atrocities on Dalits in various parts of the State. As a result of sustained agitations on the part of Dalit Panthers along with other like minded organisations over the issue of atrocities against Dalits, the government passed a comprehensive law in 1989 that provided for rigorous punishment for such acts. The larger ideological agenda of the Panthers was to destroy the caste system and to build an organisation of all oppressed sections like the landless poor peasants and urban industrial workers along with Dalits.

The movement provided a platform for Dalit educated youth to use their creativity as a protest activity. Dalit writers protested against the brutalities of the caste system in their numerous autobiographies and other literary works published during this period. These works portraying the life experiences of the most downtrodden social sections of Indian society sent shock waves in Marathi literary world, made literature more broad based and representative of different social sections and initiated contestations in the cultural realm. In the post-emergency period, Dalit Panthers got involved in electoral compromises; it also underwent many splits, which led to its decline. Organisations like the Backward and Minority Communities’ Employees Federation (BAMCEF) took over this space.

Bharatiya Kisan Union

The social discontent in Indian society since the seventies was manifold. Even those sections that partially benefited in the process of development had many complaints against the state and political parties. Agrarian struggles of the eighties is one such example where better off farmers protested against the policies of the state.

Growth

In January 1988, around twenty thousand farmers had gathered in the city of Meerut, Uttar Pradesh. They were protesting against the government decision to increase electricity rates. The farmers camped for about three weeks outside the district collector’s office until their demands were fulfilled. It was a very disciplined agitation of the farmers and all those days they received regular food supply from the nearby villages. The Meerut agitation was seen as a great show of rural power – power of farmer cultivators. These agitating farmers were members of the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU), an organisation of farmers from western Uttar Pradesh and Haryana regions. The BKU was one of the leading organisations in the farmers’ movement of the eighties.

A Bhartiya Kisan Union Rally in Punjab.

We have noted in Chapter Three that farmers of Haryana, Punjab and western Uttar Pradesh had benefited in the late 1960s from the state policies of ‘green revolution’. Sugar and wheat became the main cash crops in the region since then. The cash crop market faced a crisis in mid-eighties due to the beginning of the process of liberalisation of Indian economy. The BKU demanded higher government floor prices for sugarcane and wheat, abolition of restrictions on the inter-state movement of farm produce, guaranteed supply of electricity at reasonable rates, waiving of repayments due on loans to farmers and the provision of a government pension for farmers.

Similar demands were made by other farmers’ organisations in the country. Shetkari Sanghatana of Maharashtra declared the farmers’ movement as a war of Bharat (symbolising rural, agrarian sector) against forces of India (urban industrial sector). You have already studied in Chapter Three that the debate between industry and agriculture has been one of the prominent issues in India’s model of development. The same debate came alive once again in the eighties when the agricultural sector came under threat due to economic policies of liberalisation.

Characteristics

Activities conducted by the BKU to pressurise the state for accepting its demands included rallies, demonstrations, sit-ins, and jail bharo (courting imprisonment) agitations. These protests involved tens of thousands of farmers – sometimes over a lakh – from various villages in western Uttar Pradesh and adjoining regions. Throughout the decade of eighties, the BKU organised massive rallies of these farmers in many district headquarters of the State and also at the national capital. Another novel aspect of these mobilisations was the use of caste linkages of farmers. Most of the BKU members belonged to a single community. The organisation used traditional caste panchayats of these communities in bringing them together over economic issues. In spite of lack of any formal organisation, the BKU could sustain itself for a long time because it was based on clan networks among its members. Funds, resources and activities of BKU were mobilised through these networks.

Until the early nineties, the BKU distanced itself from all political parties. It operated as a pressure group in politics with its strength of sheer numbers. The organisation, along with the other farmers’ organisations across States, did manage to get some of their economic demands accepted. The farmers’ movement became one of the most successful social movements of the ’eighties in this respect. The success of the movement was an outcome of political bargaining powers that its members possessed. The movement was active mainly in the prosperous States of the country. Unlike most of the Indian farmers who engage in agriculture for subsistence, members of the organisations like the

BKU grew cash crops for the market. Like the BKU, farmers’ organisations across States recruited their members from communities that dominated regional electoral politics. Shetkari Sanghatana of Maharashtra and Rayata Sangha of Karnataka, are prominent examples of such organisations of the farmers.

Kisan union wants agriculture out of WTO purview

By Our Staff Correspondent

MYSORE, FEB. 15. The Bharatiya Kisan Union has warned of socio-economic upheavals in the country if India does not bargain to keep agriculture out of the purview of the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Addressing a press conference here today, the chief of the union, Mahendra Singh Tikait, and its national coordinating committee convener, M. Yudhveer Singh, warned of the impending dangers if India goes ahead and agrees to the stipulations of the WTO in the next round of meeting scheduled to be held in Hong Kong in November.

The leaders said a farmers’ rally will be taken out in New Delhi on March 17 to pressure the Government to keep agriculture out of the purview of the WTO. More than five lakh farmers from all over India are expected to attend the rally. Subsequently, the agitation will be intensified across the country.

The Hindu, Feb 16, 2005

Credit: Hindu

National Fish Workers’ Forum

Do you know that the Indian fishers constitute the second largest fishing population in the world? Both in the eastern and the western coastal areas of our country hundreds of thousands of families, mainly belonging to the indigenous fishermen communities, are engaged in the occupation of fishing. These fish workers’ lives were threatened in a major way when the government permitted entry to mechanised trawlers and technologies like bottom trawling for large-scale harvest of fish in the Indian seas. Throughout the seventies and eighties, local fish workers’ organisations fought with the State governments over the issues of their livelihood. Fisheries being a State subject, the fish workers were mostly mobilised at the regional level.

With the coming of policies of economic liberalisation in and around the mid ’eighties, these organisations were compelled to come together on a national level platform- the NFF or National Fishworkers’ Forum. Fish workers from Kerala took the main responsibility of mobilising fellow workers, including women workers from other States. Work of the NFF consolidated when in 1991 it fought its first legal battle with the Union government successfully. This was about the government’s deep sea fishing policy that opened up India’s waters to large commercial vessels including those of the multinational fishing companies. Throughout the nineties the NFF fought various legal and public battles with the government. It worked to protect the interests of those who rely on fishing for subsistence rather than those who invest in the sector for profit. In July 2002, NFF called for a nationwide strike to oppose the move of the government to issue licenses to foreign trawlers. The NFF joined hands with organisations all over the world for protecting ecology and for protecting lives of the fish workers.

Anti-Arrack Movement

Credit: Zuban

When the BKU was mobilising the farmers of the north, an altogether different kind of mobilisation in the rural areas was taking shape in the southern State of Andhra Pradesh. It was a spontaneous mobilisation of women demanding a ban on the sale of alcohol in their neighbourhoods.

Liquor Mafia take to Heels as Women Hit Back

The women of village Gundlur in Kalikari mandal of Chittoor district assembled and resolved to put an end to the sale of arrack in their village. They conveyed this resolution to the village arrack vendor. They turned back the jeep that brought arrack packets to the village. However, when the village arrack vendor informed the contractor about this, the contractor sent him a gang of men to help him resume sales. Women of the village were adamant and opposed this move. The contractor called in the police but even they had to beat a retreat. A week later, women who prevented the sale of arrack were assaulted by arrack contractor’s goondas with iron rods and other lethal weapons. But when the women resisted the assault unitedly, the hired mafia took to their heels. The women later destroyed three jeeps full of arrack.

Based on a report in Eenadu, October 29, 1992.

Credit: Zuban

Stories of this kind appeared in the Telugu press almost daily during the two months of September and October 1992. The name of the village would change in each case but the story was the same. Rural women in remote villages from the State of Andhra Pradesh fought a battle against alcoholism, against mafias and against the government during this period. These agitations shaped what was known as the anti-arrack movement in the State.

Origins

In a village in the interior of Dubagunta in Nellore district of Andhra Pradesh, women had enrolled in the Adult Literacy Drive on a large scale in the early nineteen nineties. It is during the discussion in the class that women complained of increased consumption of a locally brewed alcohol – arrack – by men in their families. The habit of alcoholism had taken deep roots among the village people and was ruining their physical and mental health. It affected the rural economy of the region a great deal. Indebtedness grew with increasing scales of consumption of alcohol, men remained absent from their jobs and the contractors of alcohol engaged in crime for securing their monopoly over the arrack trade. Women were the worst sufferers of these ill-effects of alcohol as it resulted in the collapse of the family economy and women had to bear the brunt of violence from the male family members, particularly the husband.

Credit: The Hindu

Women taking out procession in Hyderabad in 1992, protesting against the selling of arrack.

Women in Nellore came together in spontaneous local initiatives to protest against arrack and forced closure of the wine shop. The news spread fast and women of about 5000 villages got inspired and met together in meetings, passed resolutions for imposing prohibition and sent them to the District Collector. The arrack auctions in Nellore district were postponed 17 times. This movement in Nellore District slowly spread all over the State.

Linkages

The slogan of the anti-arrack movement was simple — prohibition on the sale of arrack. But this simple demand touched upon larger social, economic and political issues of the region that affected women’s life. A close nexus between crime and politics was established around the business of arrack. The State government collected huge revenues by way of taxes imposed on the sale of arrack and was therefore not willing to impose a ban. Groups of local women tried to address these complex issues in their agitation against arrack. They also openly discussed the issue of domestic violence. Their movement, for the first time, provided a platform to discuss private issues of domestic violence. Thus, the anti-arrack movement also became part of the women’s movement.

Earlier, women’s groups working on issues of domestic violence, the custom of dowry, sexual abuse at work and public places were active mainly among urban middle class women in different parts of the country. Their work led to a realisation that issues of injustice to women and of gender inequalities were complicated in nature. During the decade of the eighties women’s movement focused on issues of sexual violence against women – within the family and outside. These groups ran a campaign against the system of dowry and demanded personal and property laws based on the norms of gender equality.

Let’s watch a Film

Aakrosh

The lawyer Bhaskar Kulkarni is assigned a legal aid case to represent Bhiku Lahanya, an Adivasi who is charged with murdering his wife. The lawyer tries hard to find out the cause of the killing but the accused is determinedly silent and so is his family. The lawyer’s perseverance leads to an attack on him and also a tip off by a social worker about what had happened.

But the social worker disappears and Bhiku’s father dies. Bhiku is permitted to attend the funeral of his father. It is here that Bhiku breaks down and the ‘Aakrosh’ (screaming cry) erupts….This hard hitting film depicts the sub-human life of the oppressed and the uphill task facing any intervention against dominant social powers.

Year: 1980

Director: Govind Nihlani

Story: Vijay Tendulkar

Screenplay: Satyadev Dubey

Actors: Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri, Smita Patil, Nana Patekar, Mahesh Elkunchwar

These campaigns contributed a great deal in increasing overall social awareness about women’s questions. Focus of the women’s movement gradually shifted from legal reforms to open social confrontations like the one we discussed above. As a result the movement made demands of equal representation to women in politics during the nineties. We know that 73rd and 74th amendments have granted reservations to women in local level political offices. Demands for extending similar reservations in State and Central legislatures have also been made. A constitution amendment bill to this effect has been proposed but has not received enough support from the Parliament yet. Main opposition to the bill has come from groups, including some women’s groups, who are insisting on a separate quota for Dalit and OBC women within the proposed women’s quota in higher political offices.

Credit: India Today

Women’s demonstration in favour of anti-dowry act.

Narmada Bachao Aandolan

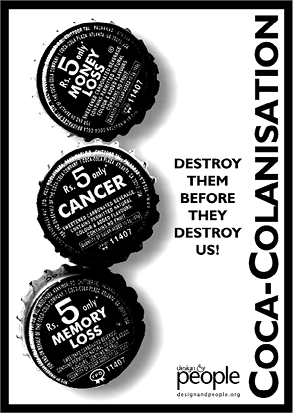

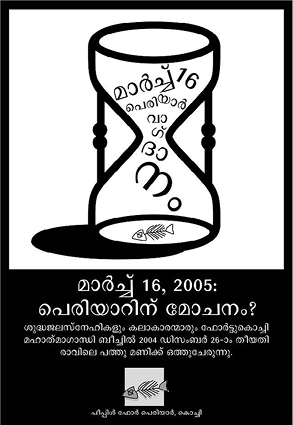

A poster in support of Narmada Bachao Andolan.

Sardar Sarovar Project

An ambitious developmental project was launched in the Narmada valley of central India in early ’eighties. The project consisted of 30 big dams, 135 medium sized and around 3,000 small dams to be constructed on the Narmada and its tributaries that flow across three states of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Maharashtra. Sardar Sarovar Project in Gujarat and the Narmada Sagar Project in Madhya Pradesh were two of the most important and biggest, multi-purpose dams planned under the project. Narmada Bachao Aandolan, a movement to save Narmada, opposed the construction of these dams and questioned the nature of ongoing developmental projects in the country.

Sardar Sarovar Project is a multipurpose mega-scale dam. Its advocates say that it would benefit huge areas of Gujarat and the three adjoining states in terms of availability of drinking water and water for irrigation, generation of electricity and increase in agricultural production. Many more subsidiary benefits like effective flood and drought control in the region were linked to the success of this dam. In the process of construction of the dam 245 villages from these States were expected to get submerged. It required relocation of around two and a half lakh people from these villages. Issues of relocation and proper rehabilitation of the project-affected people were first raised by local activist groups. It was around 1988-89 that the issues crystallised under the banner of the NBA – a loose collective of local voluntary organisations.

Debates and struggles

Credit: NBA

Credit: NBA

Top: NBA leader Medha Patkar and other activists in Jalsamadhi (protesting in rising waters) in 2002.

Bottom: A boat ralley organised by NBA.

Since its inception the NBA linked its opposition to the Sardar Sarovar Project with larger issues concerning the nature of ongoing developmental projects, efficacy of the model of development that the country followed and about what constituted public interest in a democracy. It demanded that there should be a cost-benefit analysis of the major developmental projects completed in the country so far. The movement argued that larger social costs of the developmental projects must be calculated in such an analysis. The social costs included forced resettlement of the project-affected people, a serious loss of their means of livelihood and culture and depletion of ecological resources.

Initially the movement demanded proper and just rehabilitation of all those who were directly or indirectly affected by the project. The movement also questioned the nature of decision-making processes that go in the making of mega scale developmental projects. The NBA insisted that local communities must have a say in such decisions and they should also have effective control over natural resources like water, land and forests. The movement also asked why, in a democracy, should some people be made to sacrifice for benefiting others. All these considerations led the NBA to shift from its initial demand for rehabilitation to its position of total opposition to the dam.

Arguments and agitations of the movement met vociferous opposition in the States benefiting from the project, especially in Gujarat. At the same time, the point about right to rehabilitation has been now recognised by the government and the judiciary. A comprehensive National Rehabilitation Policy formed by the government in 2003 can be seen as an achievement of the movements like the NBA. However, its demand to stop the construction of the dam was severely criticised by many as obstructing the process of development, denying access to water and to economic development for many. The Supreme Court upheld the government’s decision to go ahead with the construction of the dam while also instructing to ensure proper rehabilitation.

Narmada Bachao Aandolan continued a sustained agitation for more than twenty years. It used every available democratic strategy to put forward its demands. These included appeals to the judiciary, mobilisation of support at the international level, public rallies in support of the movement and a revival of forms of Satyagraha to convince people about the movement’s position. However, the movement could not garner much support among the mainstream political parties – including the opposition parties. In fact, the journey of the Narmada Bachao Aandolan depicted a gradual process of disjunction between political parties and social movements in Indian politics. By the end of the ’nineties, however, the NBA was not alone. There emerged many local groups and movements that challenged the logic of large scale developmental projects in their areas. Around this time, the NBA became part of a larger alliance of people’s movements that are involved in struggles for similar issues in different regions of the country.

Lessons from popular movements

The history of these popular movements helps us to understand better the nature of democratic politics. We have seen that these non-party movements are neither sporadic in nature nor are these a problem. These movements came up to rectify some problems in the functioning of party politics and should be seen as integral part of our democratic politics. They represented new social groups whose economic and social grievances were not redressed in the realm of electoral politics. Popular movements ensured effective representation of diverse groups and their demands. This reduced the possibility of deep social conflict and disaffection of these groups from democracy. Popular movements suggested new forms of active participation and thus broadened the idea of participation in Indian democracy.

Critics of these movements often argue that collective actions like strikes, sit-ins and rallies disrupt the functioning of the government, delay decision making and destabilise the routines of democracy. Such an argument invites a deeper question: why do these movements resort to such assertive forms of action? We have seen in this chapter that popular movements have raised legitimate demands of the people and have involved large scale participation of citizens. It should be noted that the groups mobilised by these movements are poor, socially and economically disadvantaged sections of the society from marginal social groups. The frequency and the methods used by the movements suggest that the routine functioning of democracy did not have enough space for the voices of these social groups. That is perhaps why these groups turned to mass actions and mobilisations outside the electoral arena.

Movement for Right to Information

Credit: Pankaj Pushkar

"Ghotala Rathyatra", a popular theatre form evolved by MKSS

The movement for Right to Information (RTI) is one of the few recent examples of a movement that did succeed in getting the state to accept its major demand. The movement started in 1990, when a mass based organisation called the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) in Rajasthan took the initiative in demanding records of famine relief work and accounts of labourers. The demand was first raised in Bhim Tehsil in a very backward region of Rajasthan. The villagers asserted their right to information by asking for copies of bills and vouchers and names of persons on the muster rolls who have been paid wages on the construction of schools, dispensaries, small dams and community centres. On paper such development projects were all completed, but it was common knowledge of the villagers that there was gross misappropriation of funds. In 1994 and 1996, the MKSS organised Jan Sunwais or Public Hearings, where the administration was asked to explain its stand in public.

Credit: Sudhir Tailang/UNDP and Planning Commission

The movement had a small success when they could force an amendment in the Rajasthan Panchayati Raj Act to permit the public to procure certified copies of documents held by the Panchayats. The Panchayats were also required to publish on a board and in newspapers the budget, accounts, expenditure, policies and beneficiaries. In 1996 MKSS formed National Council for People’s Right to Information in Delhi to raise RTI to the status of a national campaign. Prior to that, the Consumer Education and Research Center, the Press Council and the Shourie committee had proposed a draft RTI law. In 2002, a weak Freedom of Information Act was legislated but never came into force. In 2004 RTI Bill was table and received presidential assent in June 2005.

Let’s re-search

Identify at least one popular movement in your city or district in the last 25 years. Collect the following information about that movement.

- When did it start? How long did it last?

- Who were the main leaders? Which social groups supported the movement?

- What were the main issues or demands of the movement?

- Did it succeed? What was the long term effect of the movement in your area?

This can be seen in the recent case of the new economic policies. As you will read in Chapter Nine, there is a growing consensus among political parties over the implementation of these policies. It follows that those marginal social groups who may be adversely affected by these policies get less and less attention from political parties as well as the media. Therefore, any effective protest against these policies involves assertive forms of action that are taken up by the popular movements outside the framework of political parties.

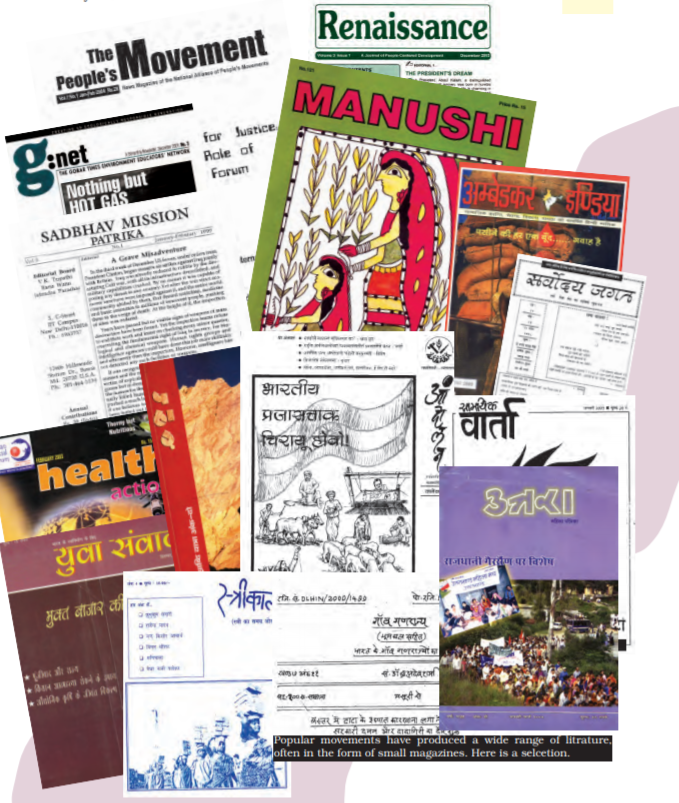

Movements are not only about collective assertions or only about rallies and protests. They involve a gradual process of coming together of people with similar problems, similar demands and similar expectations. But then movements are also about making people aware of their rights and the expectations that they can have from democratic institutions. Social movements in India have been involved in these educative tasks for a long time and have thus contributed to expansion of democracy rather than causing disruptions. The struggle for the right to information is a case in point.

Yet the real life impact of these movements on the nature of public policies seems to be very limited. This is partly because most of the contemporary movements focus on a single issue and represent the interest of one section of society. Thus it becomes possible to ignore their reasonable demands. Democratic politics requires a broad alliance of various disadvantaged social groups. Such an alliance does not seem to be shaping under the leadership of these movements. Political parties are required to bring together different sectional interests, but they also seem to be unable to do so. Parties do not seem to be taking up issues of marginal social groups. The movements that take up these issues operate in a very restrictive manner. The relationship between popular movements and political parties has grown weaker over the years, creating a vacuum in politics. In the recent years, this has become a major problem in Indian politics.

Exercises

1. Which of these statements are incorrect

The Chipko Movement

(a) was an environmental movement to prevent cutting down of trees.

(b) raised questions of ecological and economic exploitation.

(c) was a movement against alcoholism started by the women

(d) demanded that local communities should have control over their natural resources

2. Some of the statements below are incorrect. Identify the incorrect statements and rewrite those with necessary correction:

(a) Social movements are hampering the functioning of India’s democracy.

(b) The main strength of social movements lies in their mass base across social sections.

(c) Social movements in India emerged because there were many issues that political parties did not address.

3. Identify the reasons which led to the Chipko Movement in U.P in early 1970s. What was the impact of this movement?

4. The Bharatiya Kisan Union is a leading organisation highlighting the plight of farmers. What were the issues addressed by it in the nineties and to what extent were they successful?

5. The anti-arrack movement in Andhra Pradesh drew the attention of the country to some serious issues. What were these issues?

6. Would you consider the anti-arrack movement as a women’s movement? Why?

7. Why did the Narmada Bachao Aandolan oppose the dam projects in the Narmada Valley?

8. Do movements and protests in a country strengthen democracy? Justify your answer with examples.

9. What issues did the Dalit Panthers address?

10. Read the passage and answer questions below:

…., nearly all ‘new social movements’ have emerged as corrective to new maladies – environmental degradation, violation of the status of women, destruction of tribal cultures and the undermining of human rights – none of which are in and by themselves transformative of the social order. They are in that way quite different from revolutionary ideologies of the past. But their weakness lies in their being so heavily fragmented. …… …. …….a large part of the space occupied by the new social movements seem to be suffering from .. various characteristics which have prevented them from being relevant to the truly oppressed and the poor in the form of a solid unified movement of the people. They are too fragmented, reactive, ad hocish, providing no comprehensive framework of basic social change. Their being anti-this or that (anti-West, anti-capitalist, anti-development, etc) does not make them any more coherent, any more relevant to oppressed and peripheralized communities. — Rajni Kothari

(a) What is the difference between new social movements and revolutionary ideologies?

(b) What according to the author are the limitations of social movements?

(c) If social movements address specific issues, would you say that they are ‘fragmented’ or that they are more focused? Give reasons for your answer by giving examples.

LET US DO IT TOGETHER

Trace newspaper reports for a week and identify any three news stories you would classify as ‘Popular Movement’. Find out the core demands of these movements; the methods used by them to pursue their demands and the response of political parties to these demands.