Table of Contents

In this chapter…

In this last chapter we take a synoptic view of the last two decades of politics in India. These developments are complex, for various kinds of factors came together to produce unanticipated outcomes in this period. The new era in politics was impossible to foresee; it is still very difficult to understand. These developments are also controversial, for these involve deep conflicts and we are still too close to the events. Yet we can ask some questions central to the political change in this period.

- What are the implications of the rise of coalition politics for our democracy?

- What is Mandalisation all about? In which ways will it change the nature of political representation?

- What is the legacy of the Ramjanambhoomi movement and the Ayodhya demolition for the nature of political mobilisation?

- What does the rise of a new policy consensus do to the nature of political choices?

The chapter does not answer these questions. It simply gives you the necessary information and some tools so that you can ask and answer these questions when you are through with this book. We cannot avoid asking these questions just because they are politically sensitive, for the whole point of studying the history of politics in India since independence is to make sense of our present.

CHAPTER 9

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN INDIAN POLITICS

Context of the 1990s

You have read in the last chapter that Rajiv Gandhi became the Prime Minister after the assassination of Indira Gandhi. He led the Congress to a massive victory in the Lok Sabha elections held immediately thereafter in 1984. As the decade of the eighties came to a close, the country witnessed five developments that were to make a long-lasting impact on our politics.

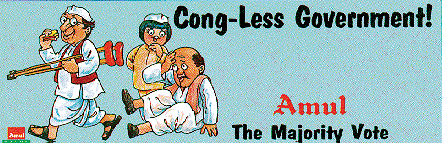

First the most crucial development of this period was the defeat of the Congress party in the elections held in 1989. The party that had won as many as 415 seats in the Lok Sabha in 1984 was reduced to only 197 in this election. The Congress improved its performance and came back to power soon after the mid-term elections held in 1991. But the elections of 1989 marked the end of what political scientists have called the ‘Congress system’. To be sure, the Congress remained an important party and ruled the country more than any other party even in this period since 1989. But it lost the kind of centrality it earlier enjoyed in the party system.

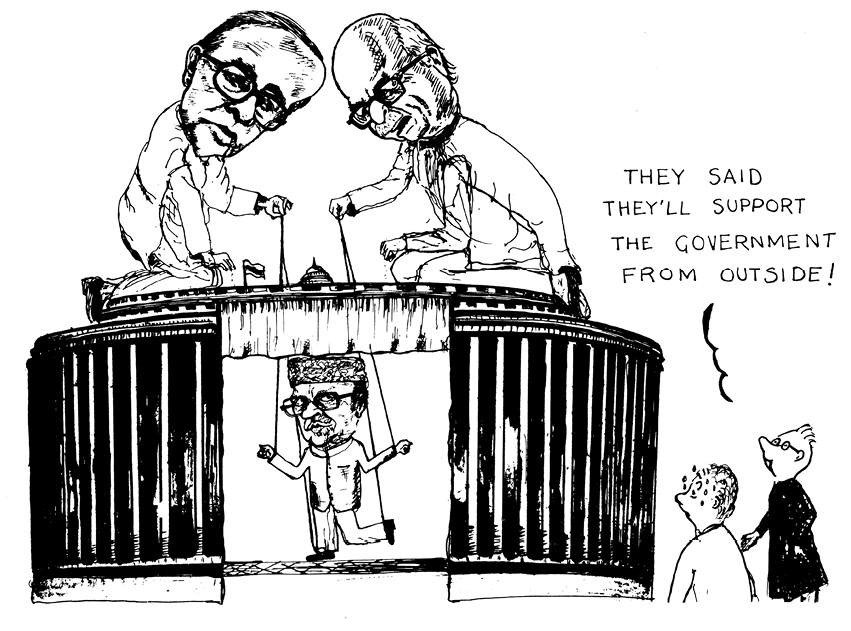

Congress leader Sitaram Kesri withdrew the crutches of support from Deve Gowda’s United Front Government.

Second development was the rise of the ‘Mandal issue’ in national politics. This followed the decision by the new National Front government in 1990, to implement the recommendation of the Mandal Commission that jobs in central government should be reserved for the Other Backward Classes. This led to violent ‘anti-Mandal’ protests in different parts of the country. This dispute between the supporters and opponents of OBC reservations was known as the ‘Mandal issue’ and was to play an important role in shaping politics since 1989.

A reaction to Mandalisation.

Third, the economic policy followed by the various governments took a radically different turn. This is known as the initiation of the structural adjustment programme or the new economic reforms. Started by Rajiv Gandhi, these changes first became very visible in 1991 and radically changed the direction that the Indian economy had pursued since independence. These policies have been widely criticised by various movements and organisations. But the various governments that came to power in this period have continued to follow these.

Credit: R. K. Laxman in the Times of India

Manmohan Singh, the then Finance Minister, with Prime Minister Narsimha Rao, in the initial phase of the ‘New Economic Policy’.

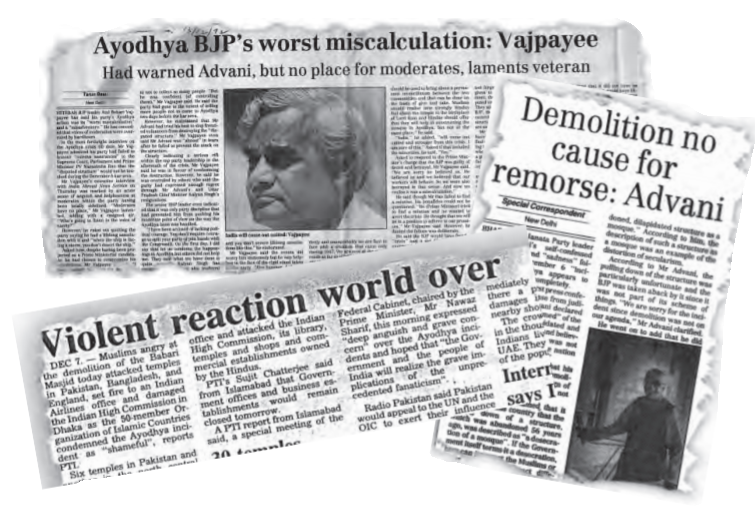

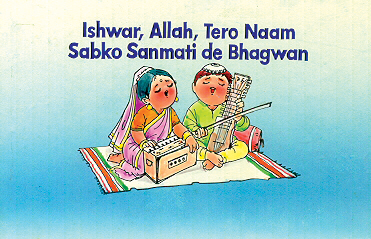

Fourth, a number of events culminated in the demolition of the disputed structure at Ayodhya (known as Babri Masjid) in December 1992. This event symbolised and triggered various changes in the politics of the country and intensified debates about the nature of Indian nationalism and secularism. These developments are associated with the rise of the BJP and the politics of ‘Hindutva’.

A reaction to rising communalism.

Finally, the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi in May 1991 led to a change in leadership of the Congress party. He was assassinated by a Sri Lankan Tamil linked to the LTTE when he was on an election campaign tour in Tamil Nadu. In the elections of 1991, Congress emerged as the single largest party. Following Rajiv Gandhi’s death, the party chose Narsimha Rao as the Prime Minister.

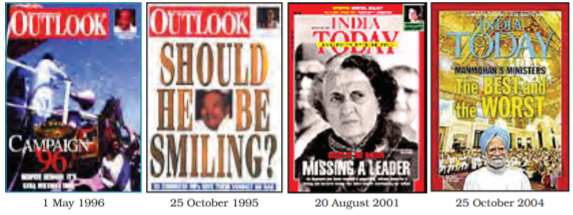

Leadership in Congress made many headlines.

Era of Coalitions

Elections in 1989 led to the defeat of the Congress party but did not result in a majority for any other party. Though the Congress was the largest party in the Lok Sabha, it did not have a clear majority and therefore, it decided to sit in the opposition. The National Front (which itself was an alliance of Janata Dal and some other regional parties) received support from two diametrically opposite political groups: the BJP and the Left Front. On this basis, the National Front formed a coalition government, but the BJP and the Left Front did not join in this government.

The National Front Government lead by V. P. Singh was supported by the Left (represented here by Jyoti Basu) as well as the BJP (represented by L. K. Advani)

Decline of Congress

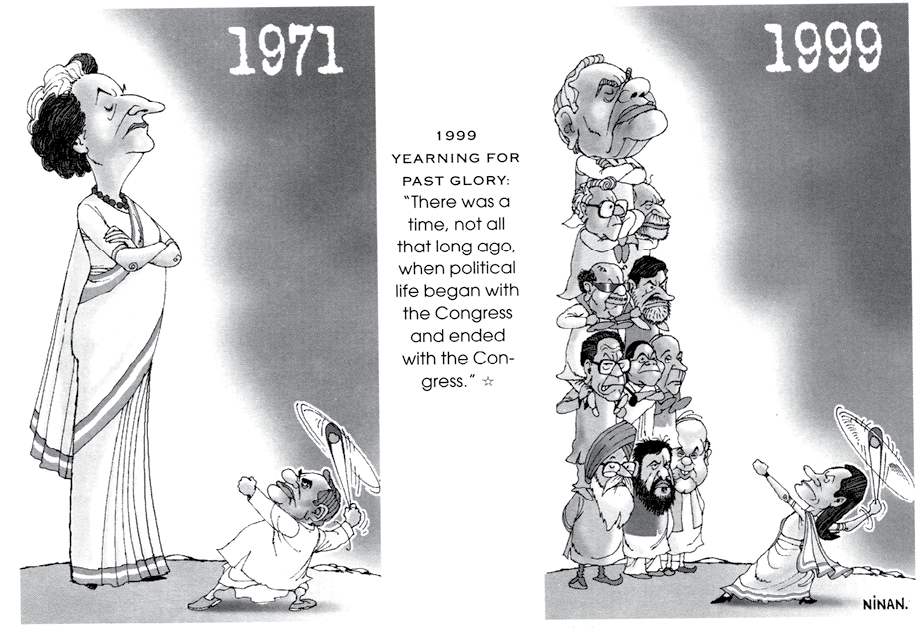

The defeat of the Congress party marked the end of Congress dominance over the Indian party system. Do you remember the discussion in chapter five about the restoration of the Congress system? Way back in the late sixties, the dominance of the Congress party was challenged; but the Congress under the leadership of Indira Gandhi, managed to re-establish its predominant position in politics. The nineties saw yet another challenge to the predominant position of the Congress. It did not, however, mean the emergence of any other single party to fill in its place.

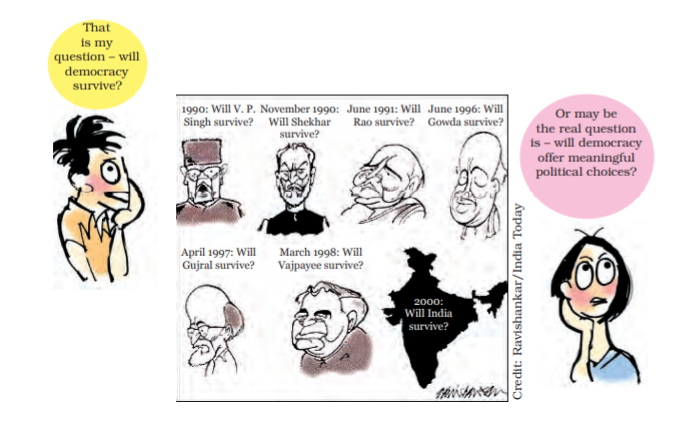

Thus, began an era of multi-party system. To be sure, a large number of political parties always contested elections in our country. Our parliament always had representatives from several political parties. What happened after 1989 was the emergence of several parties in such a way that one or two parties did not get most of the votes or seats. This also meant that no single party secured a clear majority of seats in any Lok Sabha election held since 1989 till 2014. This development initiated an era of coalition governments at the Centre, in which regional parties played a crucial role in forming ruling alliances.

Let’s re-search

Talk to your parents about their memories of the events happening since the 1990s. Ask them what they felt were the most significant events of the period. Sit together in groups and draw a comprehensive list of the events reported by your parents, see which events get cited most, and compare them with what the chapter suggests were the most significant. You can also discuss why some events are more important for some and not for others.

Alliance politics

The nineties also saw the emergence of powerful parties and movements that represented the Dalit and backward castes (Other Backward Classes or OBCs). Many of these parties represented powerful regional assertion as well. These parties played an important role in the United Front government that came to power in 1996. The United Front was similar to the National Front of 1989 for it included Janata Dal and several regional parties. This time the BJP did not support the government. The United Front government was supported by the Congress. This shows how unstable the political equations were. In 1989, both the Left and the BJP supported the National Front Government because they wanted to keep the Congress out of power. In 1996, the Left continued to support the non-Congress government but this time the Congress, supported it, as both the Congress and the Left wanted to keep the BJP out of power.

They did not succeed for long, as the BJP continued to consolidate its position in the elections of 1991 and 1996. It emerged as the largest party in the 1996 election and was invited to form the government. But most other parties were opposed to its policies and therefore, the BJP government could not secure a majority in the Lok Sabha. It finally came to power by leading a coalition government from May 1998 to June 1999 and was

re-elected in October 1999. Atal Behari Vajpayee was the Prime Minister during both these NDA governments and his government formed in 1999 completed its full term.

Credit: Ajit Ninan/India Today

A cartoonist’s depiction of the change from one-party dominance to a multi-party alliance system.

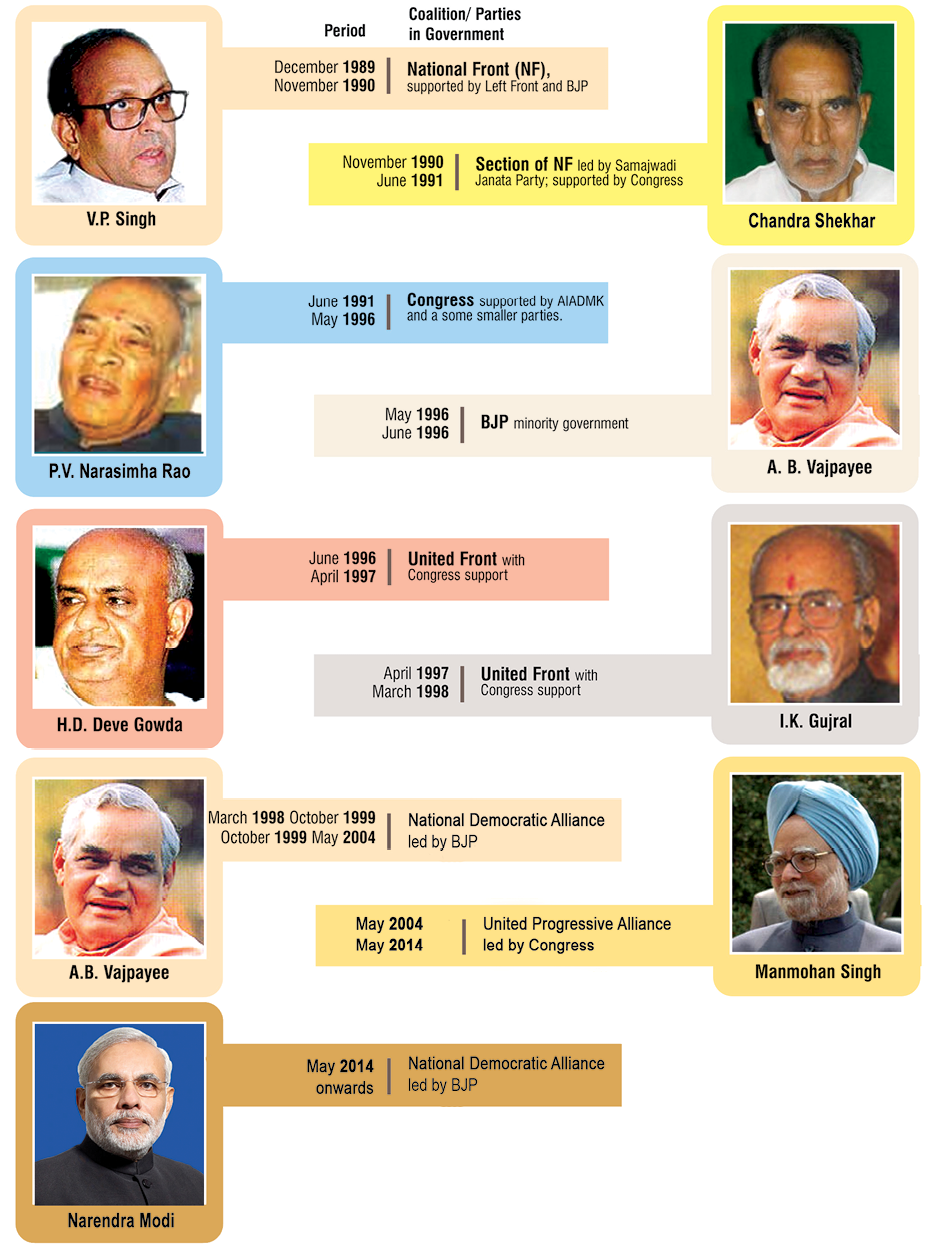

Thus, with the elections of 1989, a long phase of coalition politics began in India. Since then, there have been eleven governments at the Centre, all of which have either been coalition governments or minority governments supported by other parties, which did not join the government. In this new phase, any government could be formed only with the participation or support of many regional parties. This applied to the National Front in 1989, the United Front in 1996 and 1997, the NDA in 1997, the BJP-led coalition in 1998, the NDA in 1999, the UPA in 2004 and 2009. However, this trend changed in 2014.

Let us connect this development with what we have learnt so far. The era of coalition governments may be seen as a long-term trend resulting from relatively silent changes that were taking place over the last few decades.

We saw in chapter two that in earlier times, it was the Congress party itself that was a ‘coalition’ of different interests and different social strata and groups. This gave rise to the term ‘Congress system’.

CENTRAL GOVERNMENTS SINCE 1989

For more details about the current and former Prime Ministers, visit http://pmindia.gov.in/en

Note: The blank space is for you to record more information on the major policies, performance and controversies about that government.

We also saw in chapter five that, especially since the late 1960s, various sections had been leaving the Congress fold and forming separate political parties of their own. We also noted the rise of many regional parties in the period after 1977. While these developments weakened the Congress party, they did not enable any single party to replace the Congress.

Political Rise of Other Backward Classes

One long-term development of this period was the rise of Other Backward Classes as a political force. You have already come across this term ‘OBC’. This refers to the administrative category ‘other backward classes’. These are communities other than SC and ST who suffer from educational and social backwardness. These are also referred to as ‘backward castes’. We have already noted in chapter six that the support for the Congress among many sections of the ‘backward castes’ had declined. This created a space for non-Congress parties that drew more support from these communities. You would recall that the rise of these parties first found political expression at the national level in the form of the Janata Party government in 1977. Many of the constituents of the Janata Party, like the Bharatiya Kranti Dal and the Samyukta Socialist Party, had a powerful rural base among some sections of the OBC.

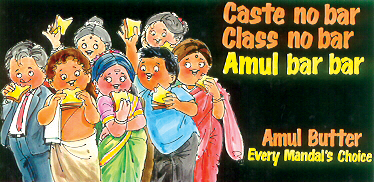

‘Mandal’ implemented

In the 1980s, the Janata Dal brought together a similar combination of political groups with strong support among the OBCs. The decision of the National Front government to implement the recommendations of the Mandal Commission further helped in shaping the politics of ‘other backward classes’. The intense national debate for and against reservation in jobs made people from the OBC communities more aware of this identity. Thus, it helped those who wanted to mobilise these groups in politics. This period saw the emergence of many parties that sought better opportunities for OBCs in education and employment and also raised the question of the share of power enjoyed by the OBCs. These parties claimed that since OBCs constituted a large segment of Indian society, it was only democratic that the OBCs should get adequate representation in administration and have their due share of political power.

Implementation of Mandal Commission report sparked off agitations and political upheavals.

The Mandal Commission

Reservations for the OBC were in existence in southern States since the 1960s, if not earlier. But this policy was not operative in north Indian States. It was during the tenure of Janata Party government in 1977-79 that the demand for reservations for backward castes in north India and at the national level was strongly raised. Karpoori Thakur, the then chief minister of Bihar, was a pioneer in this direction. His government had introduced a new policy of reservations for OBCs in Bihar. Following this, the central government appointed a Commission in 1978 to look into and recommend ways to improve the conditions of the backward classes. This was the second time since independence that the government had appointed such a commission. Therefore, this commission was officially known as the Second Backward Classes Commission. Popularly, the commission is known as the Mandal Commission, after the name of its chairperson, Bindeshwari Prasad Mandal.

B.P. Mandal (1918-1982): M.P. from Bihar for 1967-1970 and 1977-1979; chaired the Second Backward Classes Commission that recommended reservations for Other Backward Classes; a socialist leader from Bihar; Chief Minister of Bihar for just a month and a half in 1968; joined the Janata Party in 1977.

The Mandal Commission was set up to investigate the extent of educational and social backwardness among various sections of Indian society and recommend ways of identifying these ‘backward classes’. It was also expected to give its recommendations on the ways in which this backwardness could be ended. The Commission gave its recommendations in 1980. By then the Janata government had fallen. The Commission advised that ‘backward classes’ should be understood to mean ‘backward castes’, since many castes, other than the Scheduled Castes, were also treated as low in the caste hierarchy. The Commission did a survey and found that these backward castes had a very low presence in both educational institutions and in employment in public services. It therefore recommended reserving 27 per cent of seats in educational institutions and government jobs for these groups. The Mandal Commission also made many other recommendations, like, land reform, to improve the conditions of the OBCs.

In August 1990, the National Front government decided to implement one of the recommendations of Mandal Commission pertaining to reservations for OBCs in jobs in the central government and its undertakings. This decision sparked agitations and violent protests in many cities of north India. The decision was also challenged in the Supreme Court and came to be known as the ‘Indira Sawhney case’, after the name of one of the petitioners. In November 1992, the Supreme Court gave a ruling upholding the decision of the government. There were some differences among political parties about the manner of implementation of this decision. But now the policy of reservation for OBCs has support of all the major political parties of the country.

Political fallouts

The 1980s also saw the rise of political organisation of the Dalits. In 1978 the Backward and Minority Communities Employees Federation (BAMCEF) was formed. This organisation was not an ordinary trade union of government employees. It took a strong position in favour of political power to the ‘bahujan’ – the SC, ST, OBC and minorities. It was out of this that the subsequent Dalit Shoshit Samaj Sangharsh Samiti and later the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) emerged under the leadership of Kanshi Ram. The BSP began as a small party supported largely by Dalit voters in Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. But in 1989 and the 1991 elections, it achieved a breakthrough in Uttar Pradesh. This was the first time in independent India that a political party supported mainly by Dalit voters had achieved this kind of political success.

In fact, the BSP, under Kanshi Ram’s leadership was envisaged as an organisation based on pragmatic politics. It derived confidence from the fact that the bahujans (SC, ST, OBC and religious minorities) constituted the majority of the population, and were a formidable political force on the strength of their numbers. Since then the BSP has emerged as a major political player in the State and has been in government on more than one occasion. Its strongest support still comes from Dalit voters, but it has expanded its support now to various other social groups. In many parts of India, Dalit politics and OBC politics have developed independently and often in competition with each other.

Kanshi Ram (1934-2006): Proponent of Bahujan empowerment and founder of Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP); left his central government job for social and political work; founder of BAMCEF, DS-4 and finally the BSP in 1984; astute political strategist, he regarded political power as master key to attaining social equality; credited with Dalit resurgence in north Indian States.

Communalism, Secularism, Democracy

The other long-term development during this period was the rise of politics based on religious identity, leading to a debate about secularism and democracy. We noted in Chapter Six that in the aftermath of the Emergency, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh had merged into the Janata Party. After the fall of the Janata Party and its break-up, the supporters of erstwhile Jana Sangh formed the Bharatiya Janata Party ( BJP) in 1980. Initially, the BJP adopted a broader political platform than that of the Jana Sangh. It embraced ‘Gandhian Socialism’ as its ideology. But it did not get much success in the elections held in 1980 and 1984. After 1986, the party began to emphasise the Hindu nationalist element in its ideology. The BJP pursued the politics of ‘Hindutva’ and adopted the strategy of mobilising the Hindus.

Hindutva literally means ‘Hinduness’ and was defined by its originator, V. D. Savarkar, as the basis of Indian (in his language also Hindu) nationhood. It basically meant that to be members of the Indian nation, everyone must not only accept India as their ‘fatherland’ (pitrubhu) but also as their holy land (punyabhu). Believers of ‘Hindutva’ argue that a strong nation can be built only on the basis of a strong and united national culture. They also believe that in the case of India the Hindu culture alone can provide this base.

Two developments around 1986 became central to the politics of BJP as a ‘Hindutva’ party. The first was the Shah Bano case in 1985. In this case a 62-year old divorced Muslim woman, had filed a case for maintenance from her former husband. The Supreme Court ruled in her favour. The orthodox Muslims saw the Supreme Court’s order as an interference in Muslim Personal Law. On the demand of some Muslim leaders, the government passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986 that nullified the Supreme Court’s judgment. This action of the government was opposed by many women’s organisations, many Muslim groups and most of the intellectuals. The BJP criticised this action of the Congress government as an unnecessary concession and ‘appeasement’ of the minority community.

Ayodhya dispute

The second development was the order by the Faizabad district court in February 1986. The court ordered that the Babri Masjid premises be unlocked so that Hindus could offer prayers at the site which they considered as a temple. A dispute had been going on for many decades over the mosque known as Babri Masjid at Ayodhya. The Babri Masjid was a 16th century mosque in Ayodhya and was built by Mir Baqi – Mughal emperor Babur’s general. Some Hindus believe that it was built after demolishing a temple for Lord Rama in what is believed to be his birthplace. The dispute took the form of a court case and has continued for many decades. In the late 1940s the mosque was locked up as the matter was with the court.

As soon as the locks of the Babri Masjid were opened, mobilisation began on both sides. Many Hindu and Muslim organisations tried to mobilise their communities on this question. Suddenly this local dispute became a major national question and led to communal tensions. The BJP made this issue its major electoral and political plank. Along with many other organisations like the RSS and the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP), it convened a series of symbolic and mobilisational programmes. This large scale mobilisation led to surcharged atmosphere and many instances of communal violence. The BJP, in order to generate public support, took out a massive march called the Rathyatra from Somnath in Gujarat to Ayodhya in UP.

Demolition and after

In December 1992, the organisations supporting the construction of the temple had organised a Karseva, meaning voluntary service by the devotees, for building the Ram temple. The situation had become tense all over the country and especially at Ayodhya. The Supreme Court had ordered the State government to take care that the disputed site will not be endangered. However, thousands of people gathered from all over the country at Ayodhya on 6 December 1992 and demolished the mosque. This news led to clashes between the Hindus and Muslims in many parts of the country. The violence in Mumbai erupted again in January 1993 and continued for over two weeks.

Credit (Clockwise): The Pioneer, The Pioneer and The Statesman.

The events at Ayodhya led to a series of other developments. The State government, with the BJP as the ruling party, was dismissed by the Centre. Along with that, other States where the BJP was in power, were also put under president’s rule. A case against the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh was registered in the Supreme Court for contempt of court since he had given an undertaking that the disputed structure will be protected. The BJP officially expressed regret over the happenings at Ayodhya. The central government appointed a commission to investigate into the circumstances leading to the demolition of the mosque. Most political parties condemned the demolition and declared that this was against the principles of secularism. This led to a serious debate over secularism and posed the kind of questions our country faced immediately after partition – was India going to be a country where the majority religious community dominated over the minorities? Or would India continue to offer equal protection of law and equal citizenship rights to all Indians irrespective of their religion?

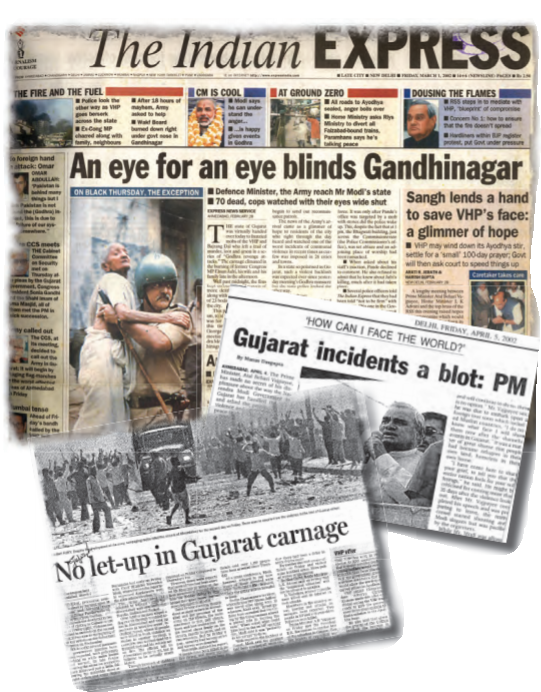

During this time, there has also been a debate about using religious sentiments for electoral purposes. India’s democratic politics is based on the premise that all religious communities enjoy the freedom that they may join any party and that there will not be community-based political parties. This democratic atmosphere of communal amity has faced many challenges since 1984. As we have read in chapter eight, this happened in 1984 in the form of anti-Sikh riots. In February-March 2002, similar violence broke out against the Muslims in Gujarat. Such violence against the minority community and violence between two communities is a threat to democracy.

"These proceedings have the echo of the disastrous event that ended in the demolition on the 6th December, 1992 of the disputed structure of ‘Ram Janam Bhoomi-Babri Masjid’ in Ayodhya. Thousands of innocent lives of citizens were lost, extensive damage to property caused and more than all a damage to the image of this great land as one fostering great traditions of tolerance, faith, brotherhood amongst the various communities inhabiting the land was impaired in the international scene.

It is unhappy that a leader of a political party and the Chief Minister has to be convicted of an offence of Contempt of Court. But it has to be done to uphold the majesty of law. We convict him of the offence of contempt of Court. Since the contempt raises larger issues which affect the very foundation of the secular fabric of our nation, we also sentence him to a token imprisonment of one day."

Chief Justice Venkatachaliah and Justice G.N. Ray of Supreme Court

Observations in a judgement on the failure of the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh to keep the promise that he had made before the National Integration Council to protect the ‘Ram Janam Bhumi-Babri Masjid’ structure, Mohd. Aslam v. Union of India, 24 October 1994

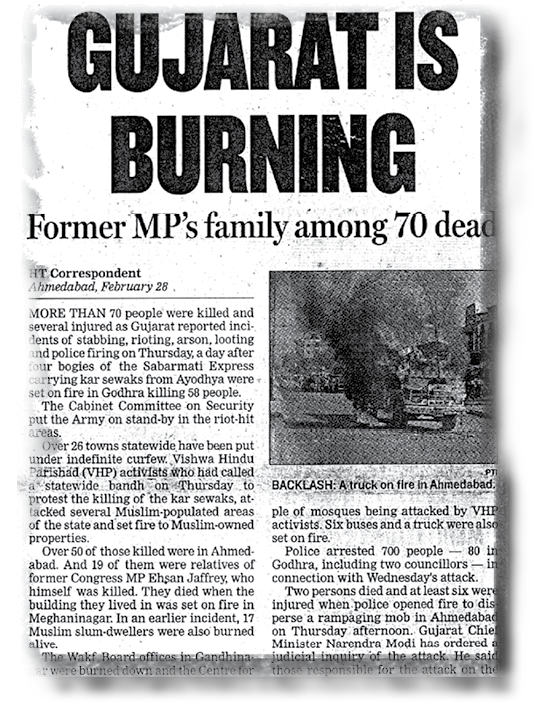

Gujarat riots

In February-March 2002, large-scale violence took place in Gujarat. The immediate provocation for this violence was an incident that took place at a station called Godhra. A bogey of a train that was returning from Ayodhya and was full of Karsevaks was set on fire. Fifty- seven people died in that fire. Suspecting the hand of the Muslims in setting fire to the bogey, large-scale violence against Muslims began in many parts of Gujarat from the next day. This violence continued for almost a whole month. Nearly 1100 persons, mostly Muslims, were killed in this violence. The National Human Rights Commission criticised the Gujarat government’s role in failing to control violence, provide relief to the victims and prosecute the perpetrators of this violence. The Election Commission of India ordered the assembly elections to be postponed. As in the case of anti-Sikh riots of 1984, Gujarat riots show that the governmental machinery also becomes susceptible to sectarian passions. Instances, like in Gujarat, alert us to the dangers involved in using religious sentiments for political purposes. This poses a threat to democratic politics.

"On 27 February1947, at the very first meeting of the Advisory Committee of the Constituent Assembly on Fundamental Rights, Minorities and Tribals and Excluded Areas, Sardar Patel asserted:

“It is for us to prove that it is a bogus claim, a false claim, and that nobody can be more interested than us, in India, in the protection of our minorities. Our mission is to satisfy every one of them. Let us prove we can rule ourselves and we have no ambition to rule others”.

“The tragic events in Gujarat, starting with the Godhra incident and continuing with the violence that rocked the state for over two months, have greatly saddened the nation. There is no doubt, in the opinion of the Commission, that there was a comprehensive failure on the part of the state government to control the persistent violation of the rights to life, liberty, equality and dignity of the people of the state. It is, of course, essential to heal the wounds and to look to a future of peace and harmony. But the pursuit of these high objectives must be based on justice and upholding of the values of the constitution of the republic and the laws of the land."

National Human Rights Commission, Annual Report 2001-2002.

Emergence of a new consensus

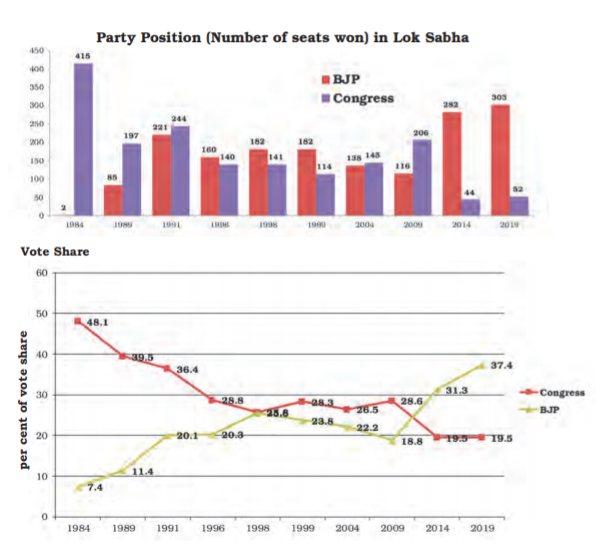

The period after 1989 is seen sometimes as the period of decline of Congress and rise of BJP. If you want to understand the complex nature of political competition in this period, you have to compare the electoral performances of the Congress and the BJP.

Now let us try to understand the meaning of the information given in the figure.

- You will notice that BJP and Congress were engaged in a tough competition in this period. What is the difference between their electoral fortunes if you compare these with the 1984 elections?

- You will notice that since the 1989 election, the votes polled by the two parties, Congress and the BJP do not add up to more than fifty per cent. The seats won by them too, do not add up to more than half the seats in the Lok Sabha. So, where did the rest of the votes and seats go?

- Look at both the charts showing Congress and Janata ‘family’ of parties. Which among the parties that exist today are neither part of Congress family of parties nor part of Janata family of parties?

- The political competition during the nineties is divided between the coalition led by BJP and the coalition led by the Congress. Can you list the parties that are not part of any of these two coalitions?

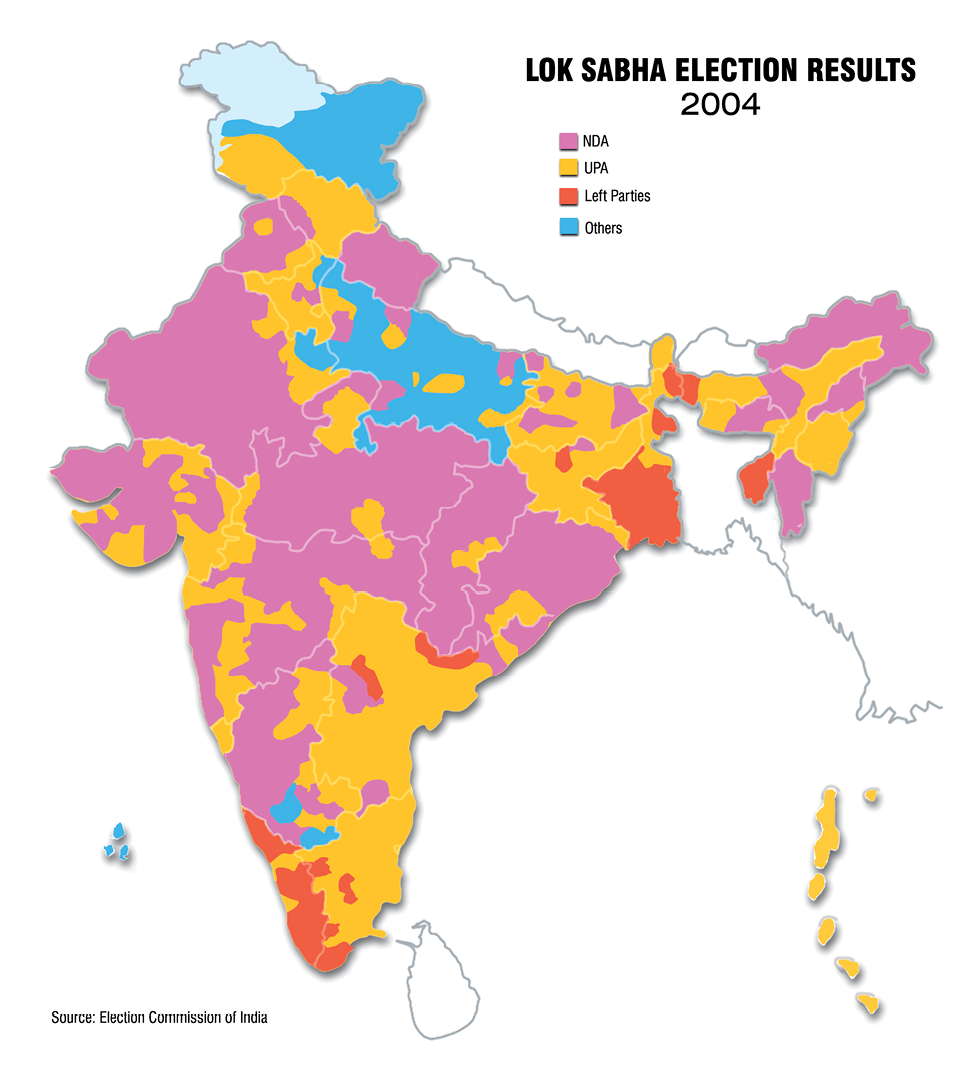

Lok Sabha Elections 2004

In the elections of 2004, the Congress party too entered into coalitions in a big way. The NDA was defeated and a new coalition government led by the Congress, known as the United Progressive Alliance came to power. This government received support from the Left Front parties. The elections of 2004 also witnessed the partial revival of Congress party. It could increase its seats for the first time since 1991. However, in the 2004 elections, there was a negligible difference between the votes polled by the Congress and its allies and the BJP and its allies. Thus, the party system has now changed almost dramatically from what it was till the seventies.

The political processes that are unfolding around us after the 1990s show the emergence of broadly four groups of parties – parties that are in coalition with the Congress; parties that are in alliance with the BJP; Left Front parties; and other parties who are not part of any of these three. The situation suggests that political competition will be multi-cornered. By implication the situation also assumes a divergence of political ideologies.

Growing consensus

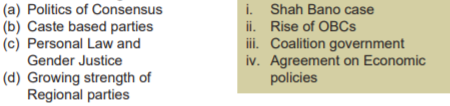

However, on many crucial issues, a broad agreement has emerged among most parties. In the midst of severe competition and many conflicts, a consensus appears to have emerged among most parties. This consensus consists of four elements.

First, agreement on new economic policies – while many groups are opposed to the new economic policies, most political parties are in support of the new economic policies. Most parties believe that these policies would lead the country to prosperity and a status of economic power in the world.

Note: This illustration is not a map drawn to scale and should not be taken to be an authentic depiction of India’s external boundaries.

Second, acceptance of the political and social claims of the backward castes – political parties have recognised that the social and political claims of the backward castes need to be accepted. As a result, all political parties now support reservation of seats for the ‘backward classes’ in education and employment. Political parties are also willing to ensure that the OBCs get adequate share of power.

Third, acceptance of the role of State level parties in governance of the country – the distinction between State level and national level parties is fast becoming less important. As we saw in this chapter, State level parties are sharing power at the national level and have played a central role in the country’s politics of last twenty years or so.

Fourth, emphasis on pragmatic considerations rather than ideological positions and political alliances without ideological agreement – coalition politics has shifted the focus of political parties from ideological differences to power sharing arrangements. Thus, most parties of the NDA did not agree with the ‘Hindutva’ ideology of the BJP. Yet, they came together to form a government and remained in power for a full term.

All these are momentous changes and are going to shape politics in the near future. We started this study of politics in India with the discussion of how the Congress emerged as a dominant party. From that situation, we have now arrived at a more competitive politics, but politics that is based on a certain implicit agreement among the main political actors. Thus, even as political parties act within the sphere of this consenus, popular movements and organisations are simultaneously identifying new forms, visions and pathways of development. Issues like poverty, displacement, minimum wages, livelihood and social security are being put on the political agenda by peoples’ movements, reminding the state of its responsibility. Similarly, issues of justice and democracy are being voiced by the people in terms of class, caste, gender and regions. We cannot predict the future of democracy. All we know is that democratic politics is here to stay in India and that it will unfold through a continuous churning of some of the factors mentioned in this chapter.

Source: http://loksabha.nic.in

EXERCISES

1. Unscramble a bunch of disarranged press clipping file of Unni-Munni… and arrange the file chronologically.

(a) Mandal Recommendations and Anti Reservation Stir

(b) Formation of the Janata Dal

(c) The demolition of Babri Masjid

(d) Assassination of Indira Gandhi

(e) The formation of NDA government

(f) Godhra incident and its fallout

(g) Formation of the UPA government

2. Match the following.

3. State the main issues in Indian politics in the period after 1989. What different configurations of political parties these differences lead to?

4. “In the new era of coalition politics, political parties are not aligning or re-aligning on the basis of ideology.” What arguments would you put forward to support or oppose this statement?

5. Trace the emergence of BJP as a significant force in post-Emergency politics.

6. In spite of the decline of Congress dominance, the Congress party continues to influence politics in the country. Do you agree? Give reasons.

7. Many people think that a two-party system is required for successful democracy. Drawing from India’s experience of last 30 years, write an essay on what advantages the present party system in India has.

8. Read the passage and answer the questions below:

Party politics in India has confronted numerous challenges. Not only has the Congress system destroyed itself, but the fragmentation of the Congress coalition has triggered a new emphasis on self-representation which raises questions about the party system and its capacity to accommodate diverse interests, …. . An important test facing the polity is to evolve a party system or political parties that can effectively articulate and aggregate a variety of interests. — Zoya Hasan

(a) Write a short note on what the author calls challenges of the

party system in the light of what you have read in this chapter.

(b) Given an example from this chapter of the lack of accommodation and aggregation mentioned in this passage.

(c) Why is it necessary for parties to accommodate and aggregate variety of interests?

LET US DO IT TOGETHER

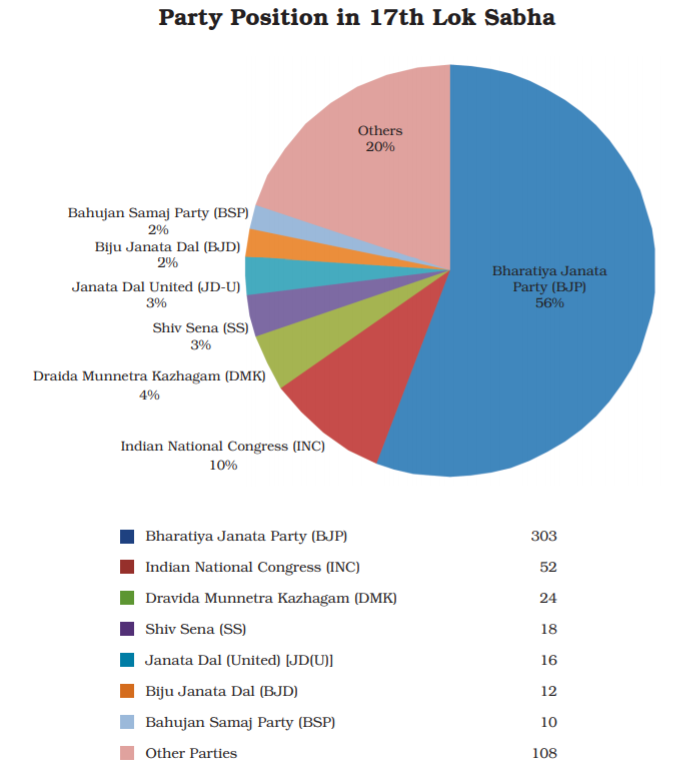

- This chapter covers the major developments in Indian politics until the 2004 Elections (14th Lok Sabha). Subsequently, the Lok Sabha elections were held in 2009, during which the UPA led by the Congress won. In the 2014 and 2019 Elections, the NDA led by the BJP emerged victorious. The position of various parties in the 17th Lok Sabha is given on page 193.

- A detailed study of Members of the 17th Lok Sabha is available on the website of the Lok Sabha (http://loksabha.nic.in).

- Compare and contrast the electoral performances of various political parties since 2004. The table given below can be used for this. You can also collect the data about the results from the website of the Election Commission of India (http://eci.nic.in).

- Prepare a timeline of the major political events in India since 2004. Share and discuss it in your classroom.

Party Positions in Indian Parliament since 2004

|

| Party | 2004 | 2009 | 2014 | 2019 |

| 1 | Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) | - | - | 4 | 1 |

| 2 | All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) | 0 | 9 | 37 | 1 |

| 3 | 19 | 21 | - | 10 | |

| 4 | 138 | 116 | 282 | 303 | |

| 5 | 11 | 14 | 20 | 12 | |

| 6 | 43 | 16 | 9 | 3 | |

| 7 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 2 | |

| 8 | 16 | 18 | - | 24 | |

| 9 | 145 | 206 | 44 | 52 | |

| 10 | 8 | 20 | 2 | 16 | |

| 11 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| 12 | 4 | - | 6 | 6 | |

| 13 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 5 | |

| 14 | 24 | 4 | 4 | - | |

| 15 | 3 | 5 | 1 | - | |

| 16 | 36 | 23 | 5 | 5 | |

| 17 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2 | |

| 18 | 12 | 11 | 18 | 18 | |

| 19 | Others | 54 | 60 | 98 | 82 |

|

| Total | 543 | 543 | 543 | 543 |

Total Positions in Indian Parliament : 545 (530 from States, 13 from UTs and 2 from Anglo-Indian Community are nominated by President)