Table of Contents

Chapter 7

Social influence and group processes

After reading this chapter, you would be able to:

- understand the nature and types of groups and know how they are formed,

- examine the influence of group on individual behaviour,

- describe the process of cooperation and competition,

- reflect on the importance of social identity, and

- understand the nature of intergroup conflict and examine conflict resolution strategies.

Contents

Introduction

Nature and Formation of Groups

Groupthink (Box 7.1)

Type of Groups

The Minimal Group Paradigm Experiments (Box 7.2)

Influence of Group on Individual Behaviour

Social Loafing

Group Polarisation

Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

The Autokinetic Effect (Box 7.3)

Group Pressure and Conformity : The Asch Experiment (Box 7.4)

Cooperation and Competition

Sherif’s Summer Camp Experiments (Box 7.5)

Determinants of Cooperation and Competition

Social Identity

Intergroup Conflict : Nature and Causes

Conflict Resolution Strategies

Key Terms

Summary

Review Questions

Project Ideas

Weblinks

Pedagogical Hints

Introduction

Think about your day-to-day life and the various social interactions you have. In the morning, before going to school, you interact with your family members; in school, you discuss topics and issues with your teachers and classmates; and after school you phone up, visit or play with your friends. In each of these instances, you are part of a group which not only provides you the needed support and comfort but also facilitates your growth and development as an individual. Have you ever been away to a place where you were without your family, school, and friends? How did you feel? Did you feel there was something vital missing in your life?

Our lives are influenced by the nature of group membership we have. It is, therefore, important to be part of groups which would influence us positively and help us in becoming good citizens. In this chapter, we shall try to understand what groups are and how they influence our behaviour. At this point, it is also important to acknowledge that not only do others influence us, but we, as individuals, are also capable of changing others and the society. The benefits of cooperation and competition and how they influence our personal and social lives will also be examined. We will also see how identity develops — how we come to know ourselves. Similarly, we would try to understand why sometimes group conflicts arise; examine the perils of group conflict and apprise ourselves of various conflict resolution strategies so that we are able to contribute towards making a harmonious and cohesive society.

Nature and Formation of Groups

What is a Group?

The preceding introduction illustrates the importance of groups in our lives. One question that comes to mind is: “How are groups (e.g., your family, class, and the group with which you play) different from other collections of people?” For example, people who have assembled to watch a cricket match or your school function are at one place, but are not interdependent on each other. They do not have defined roles, status and expectations from each other. In the case of your family, class, and the group with which you play, you

will realise that there is mutual interdependence, each member has roles, there are status differentials, and there are expectations from each other. Thus, your family, class and playgroup are examples of groups and are different from other collections of people.

A group may be defined as an organised system of two or more individuals, who are interacting and interdependent, who have common motives, have a set of role relationships among its members, and have norms that regulate the behaviour of its members.

Groups have the following salient characteristics :

• A social unit consisting of two or more individuals who perceive themselves as belonging to the group. This characteristic of the group helps in distinguishing one group from the other and gives the group its unique identity.

• A collection of individuals who have common motives and goals. Groups function either working towards a given goal, or away from certain threats facing the group.

• A collection of individuals who are interdependent, i.e. what one is doing may have consequences for others. Suppose one of the fielders in a cricket team drops an important catch during a match — this will have consequence for the entire team.

• Individuals who are trying to satisfy a need through their joint association also influence each other.

• A gathering of individuals who interact with one another either directly or indirectly.

• A collection of individuals whose interactions are structured by a set of roles and norms. This means that the group members perform the same functions every time the group meets and the group members adhere to group norms. Norms tell us how we ought to behave in the group and specify the behaviours expected from group members.

Groups can be differentiated from other collections of people. For example, a crowd is also a collection of people who may be present at a place/situation by chance. Suppose you are going on the road and an accident takes place. Soon a large number of people tend to collect. This is an example of a crowd. There is neither any structure nor feeling of belongingness in a crowd. Behaviour of people in crowds is irrational and there is no interdependence among members.

Teams are special kinds of groups. Members of teams often have comple-mentary skills and are committed to a common goal or purpose. Members are mutually accountable for their activities. In teams, there is a positive synergy attained through the coordinated efforts of the members. The main differences between groups and teams are:

• In groups, performance is dependent on contributions of individual members. In teams, both individual contributions and teamwork matter.

• In groups, the leader or whoever is heading the group holds responsibility for the work. However in teams, although there is a leader, members hold themselves responsible.

An audience is also a collection of people who have assembled for a special purpose, may be to watch a cricket match or a movie. Audiences are generally passive but sometimes they go into a frenzy and become mobs. In mobs, there is a definite sense of purpose. There is polarisation in attention, and actions of persons are in a common direction. Mob behaviour is characterised by homogeneity of thought and behaviour as well as impulsivity.

Fig.7.1 : Look at these Two Pictures

Picture A shows a football team — a group in which members interact with one another, have roles and goals. Picture B depicts an audience watching the football match — a mere collection of people who by some coincidence (may be their interest in football) happened to be in the same place at the same time.

Why Do People Join Groups?

All of you are members of your family, class and groups with which you interact or play. Similarly, other people are also members of a number of groups at any given time. Different groups satisfy different needs, and therefore, we are simultaneously members of different groups. This sometimes creates pressures for us because there may be competing demands and expectations. Most often we are able to handle these competing demands and expectations. People join groups because these groups satisfy a range of needs. In general, people join groups for the following reasons :

• Security : When we are alone, we feel insecure. Groups reduce this insecurity. Being with people gives a sense of comfort, and protection. As a result, people feel stronger, and are less vulnerable to threats.

• Status : When we are members of a group that is perceived to be important by others, we feel recognised and experience a sense of power. Suppose your school wins in an inter- institutional debate competition, you feel proud and think that you are better than others.

• Self-esteem : Groups provide feelings of self-worth and establish a positive social identity. Being a member of prestigious groups enhances one’s self-concept.

• Satisfaction of one’s psychological and social needs : Groups satisfy one’s social and psychological needs such as sense of belongingness, giving and receiving attention, love, and power through a group.

• Goal achievement : Groups help in achieving such goals which cannot be attained individually. There is power in the majority.

• Provide knowledge and information : Group membership provides knowledge and information and thus broadens our view. As individuals, we may not have all the required information. Groups supplement this information and knowledge.

Group Formation

In this section, we will see how groups are formed. Basic to group formation is some contact and some form of interaction between people. This interaction is facilitated by the following conditions:

• Proximity : Just think about your group of friends. Would you have been friends if you were not living in the same colony, or going to the same school, or may be playing in the same playground? Probably your answer would be ‘No’. Repeated interactions with the same set of individuals give us a chance to know them, and their interests and attitudes. Common interests, attitudes, and background are important determinants of your liking for your group members.

• Similarity : Being exposed to someone over a period of time makes us assess our similarities and paves the way for formation of groups. Why do we like people who are similar? Psychologists have given several explanations for this. One explanation is that people prefer consistency and like relationships that are consistent. When two people are similar, there is consistency and they start liking each other. For example, you like playing football and another person in your class also loves playing football; there is a matching of your interests. There are higher chances that you may become friends. Another explanation given by psychologists is that when we meet similar people, they reinforce and validate our opinions and values, we feel we are right and thus we start liking them. Suppose you are of the opinion that too much watching of television is not good, because it shows too much violence. You meet someone who also has similar views. This validates your opinion, and you start liking the person who was instrumental in validating your opinion.

• Common motives and goals : When people have common motives or goals, they get together and form a group which may facilitate their goal attainment. Suppose you want to teach children in a slum area who are unable to go to school. You cannot do this alone because you have your own studies and homework. You, therefore, form a group of like-minded friends and start teaching these children. So you have been able to achieve what you could not have done alone.

Stages of Group Formation

Remember that, like everything else in life, groups develop. You do not become a group member the moment you come together. Groups usually go through different stages of formation, conflict, stabilisation, performance, and dismissal. Tuckman suggested that groups pass through five developmental sequences. These are: forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning.

• When group members first meet, there is a great deal of uncertainty about the group, the goal, and how it is to be achieved. People try to know each other and assess whether they will fit in. There is excitement as well as apprehensions. This stage is called the forming stage.

• Often, after this stage, there is a stage of intragroup conflict which is referred to as storming. In this stage, there is conflict among members about how the target of the group is to be achieved, who is to control the group and its resources, and who is to perform what task. When this stage is complete, some sort of hierarchy of leadership in the group develops and a clear vision as to how to achieve the group goal.

• The storming stage is followed by another stage known as norming. Group members by this time develop norms related to group behaviour. This leads to development of a positive group identity.

• The fourth stage is performing. By this time, the structure of the group has evolved and is accepted by group members. The group moves towards achieving the group goal. For some groups, this may be the last stage of group development.

• However, for some groups, for example, in the case of an organising committee for a school function, there may be another stage known as adjourning stage. In this stage, once the function is over, the group may be disbanded.

Activity 7.1

Identifying Stages of Group Formation

Select 10 members from your class randomly and form a committee to plan an open house. See how they go ahead. Give them full autonomy to do all the planning. Other members of the class observe them as they function.

Do you see any of these stages emerging? Which were those? What was the order of stages? Which stages were skipped?

Discuss in the class.

owever, it must be stated that all groups do not always proceed from one stage to the next in such a systematic manner. Sometimes several stages go on simultaneously, while in other instances groups may go back and forth through the various stages or they may just skip some of the stages.

During the process of group formation, groups also develop a structure. We should remember that group structure develops as members interact. Over time this interaction shows regularities in distribution of task to be performed, responsibilities assigned to members, and the prestige or relative status of members. Four important elements of group structure are :

• Roles are socially defined expectations that individuals in a given situation are expected to fulfil. Roles refer to the typical behaviour that depicts a person in a given social context. You have the role of a son or a daughter and with this role, there are certain role expectations, i.e. including the behaviour expected of someone in a particular role. As a daughter or a son, you are expected to respect elders, listen to them, and be responsible towards your studies.

• Norms are expected standards of behaviour and beliefs established, agreed upon, and enforced by group members. They may be considered as a group’s ‘unspoken rules’. In your family, there are norms that guide the behaviour of family members. These norms represent shared ways of viewing the world.

Box 7.1

Groupthink

Generally teamwork in groups leads to beneficial results. However, Irving Janis has suggested that cohesion can interfere with effective leadership and can lead to disastrous decisions. Janis discovered a process known as “groupthink” in which a group allows its concerns for unanimity. They, in fact, “override the motivation to realistically appraise courses of action”. It results in the tendency of decision makers to make irrational and uncritical decisions. Groupthink is characterised by the appearance of consensus or unanimous agreement within a group. Each member believes that all members agree upon a particular decision or a policy. No one expresses dissenting opinion because each person believes it would undermine the cohesion of the group and s/he would be unpopular. Studies have shown that such a group has an exaggerated sense of its own power to control events, and tends to ignore or minimise cues from the real world that suggest danger to its plan. In order to preserve the group’s internal harmony and collective well-being, it becomes increasingly out-of-touch with reality. Groupthink is likely to occur in socially homogenous, cohesive groups that are isolated from outsiders, that have no tradition of considering alternatives, and that face a decision with high costs or failures. Examples of several group decisions at the international level can be cited as illustrations of groupthink phenomenon. These decisions turned out to be major fiascos. The Vietnam War is an example. From 1964 to 1967, President Lyndon Johnson and his advisors in the U.S. escalated the Vietnam War thinking that this would bring North Vietnam to the peace table. The escalation decisions were made despite warnings. The grossly miscalculated move resulted in the loss of 56,000 American and more than one million Vietnamese lives and created huge budget deficits. Some ways to counteract or prevent groupthink are: (i) encouraging and rewarding critical thinking and even disagreement among group members, (ii) encouraging groups to present alternative courses of action, (iii) inviting outside experts to evaluate the group’s decisions, and (iv) encouraging members to seek feedback from trusted others.

• Status refers to the relative social position given to group members by others. This relative position or status may be either ascribed (given may be because of one’s seniority) or achieved (the person has achieved status because of expertise or hard work). By being members of the group, we enjoy the status associated with that group. All of us, therefore, strive to be members of such groups which are high in status or are viewed favourably by others. Even within a group, different members have different prestige and status. For example, the captain of a cricket team has a higher status compared to the other members, although all are equally important for the team’s success.

• Cohesiveness refers to togetherness, binding, or mutual attraction among group members. As the group becomes more cohesive, group members start to think, feel and act as a social unit, and less like isolated individuals. Members of a highly cohesive group have a greater desire to remain in the group in comparison to those who belong to low cohesive groups. Cohesiveness refers to the team spirit or ‘we feeling’ or a sense of belongingness to the group. It is difficult to leave a cohesive group or to gain membership of a group which is highly cohesive. Extreme cohesiveness however, may sometimes not be in a group’s interest. Psychologists have identified the phenomenon of groupthink (see Box 7.1) which is a consequence of extreme cohesiveness.

Type of Groups

Groups differ in many respects; some have a large number of members (e.g., a country), some are small (e.g., a family), some are short-lived (e.g., a committee), some remain together for many years (e.g., religious groups), some are highly organised (e.g., army, police, etc.), and others are informally organised (e.g., spectators of a match). People may belong to different types of group. Major types of groups are enumerated below :

• primary and secondary groups

• formal and informal groups

• ingroup and outgroup.

Primary and Secondary Groups

A major difference between primary and secondary groups is that primary groups are pre-existing formations which are usually given to the individual whereas secondary groups are those which the individual joins by choice. Thus, family, caste, and religion are primary groups whereas membership of a political party is an example of a secondary group. In a primary group, there is a face-to-face interaction, members have close physical proximity, and they share warm emotional bonds. Primary groups are central to individual’s functioning and have a very major role in developing values and ideals of the individual during the early stages of development. In contrast, secondary groups are those where relationships among members are more impersonal, indirect, and less frequent. In the primary group, boundaries are less permeable, i.e. members do not have the option to choose its membership as compared to secondary groups where it is easy to leave and join another group.

Formal and Informal Groups

These groups differ in the degree to which the functions of the group are stated explicitly and formally. The functions of a formal group are explicitly stated as in the case of an office organisation. The roles to be performed by group members are stated in an explicit manner. The formal and informal groups differ on the basis of structure. The formation of formal groups is based on some specific rules or laws and members have definite roles. There are a set of norms which help in establishing order. A university is an example of a formal group. On the other hand, the formation of informal groups is not based on rules or laws and there is close relationship among members.

Ingroup and Outgroup

Just as individuals compare themselves with others in terms of similarities and differences with respect to what they have and what others have, individuals also compare the group they belong to with groups of which they are not a member. The term ‘ingroup’ refers to one’s own group, and ‘outgroup’ refers to another group. For ingroup members, we use the word ‘we’ while for outgroup members, the word ‘they’ is used. By using the words they and we, one is categorising people as similar or different. It has been found that persons in the ingroup are generally supposed to be similar, are viewed favourably, and have desirable traits. Members of the outgroup are viewed differently and are often perceived negatively in comparison to the ingroup members. Perceptions of ingroup and outgroup affect our social lives. These differences can be easily understood by studying Tajfel’s experiments given in Box 7.2.

Although it is common to make these categorisations, it should be appreciated that these categories are not real and are created by us. In some cultures, plurality is celebrated as has been the case in India. We have a unique composite culture which is reflected not only in the lives we live, but also in our art, architecture, and music.

Activity 7.2

Ingroup and Outgroup Distinctions

Think of any interinstitutional competition held in the near past. Ask your friends to write a paragraph about your school and its students, and about another school and students of that school. Ask the class and list the behaviour and characteristics of your schoolmates, and students of the other school on the board. Observe the differences and discuss in the class. Do you also see similarities? If yes, discuss them too.

Box 7.2

The Minimal Group Paradigm Experiments

Tajfel and his colleagues were interested in knowing the minimal conditions for intergroup behaviour. ‘Minimal group paradigm’ was developed to answer this question. British school-boys expressed their preference for paintings by two artists — Vassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. Children were told that it was an experiment on decision-making. They knew the groups in which they were grouped (Kandinsky group and Klee group). The identity of other group members was hidden using code numbers. The children then distributed money between recipients only by code number and group membership.

Sample distribution matrix :

Ingroup member — 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

Outgroup member — 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25

You will agree that these groups were created on a flimsy criterion (i.e. preference for paintings by two artists) which had no past history or future. Yet, results showed that children favoured their own group.

Influence of Group on Individual Behaviour

We have seen that groups are powerful as they are able to influence the behaviour of individuals. What is the nature of this influence? What impact does the presence of others have on our performance? We will discuss two situations : (i) an individual performing an activity alone in the presence of others (social facilitation), and (ii) an individual performing an activity along with the others as part of a larger group (social loafing). Since social facilitation has been briefly discussed in Chapter 6, we would try to understand the phenomenon of social loafing in this section.

Social Loafing

Social facilitation research suggests that presence of others leads to arousal and can motivate individuals to enhance their performance if they are already good at solving something. This enhancement occurs when a person’s efforts are individually evaluated. What would happen if efforts of an individual in a group are pooled so that you look at the performance of the group as a whole? Do you know what often happens? It has been found that individuals work less hard in a group than they do when performing alone. This points to a phenomenon referred to as ‘social loafing’. Social loafing is a reduction in individual effort when working on a collective task, i.e. one in which outputs are pooled with those of other group members. An example of such a task is the game of tug-of-war. It is not possible for you to identify how much force each member of the team has been exerting. Such situations give opportunities to group members to relax and become a free rider. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in many experiments by Latane and his associates who asked group of male students to clap or cheer as loudly as possible as they (experimenters) were interested in knowing how much noise people make in social settings. They varied the group size; individuals were either alone, or in groups of two, four and six. The results of the study showed that although the total amount of noise rose up, as size increased, the amount of noise produced by each participant dropped. In other words, each participant put in less effort as the group size increased. Why does social loafing occur? The explanations offered are:

• Group members feel less responsible for the overall task being performed and therefore exert less effort.

• Motivation of members decreases because they realise that their contributions will not be evaluated on individual basis.

• The performance of the group is not to be compared with other groups.

• There is an improper coordination (or no coordination) among members.

• Belonging to the same group is not important for members. It is only an aggregate of individuals.

Social loafing may be reduced by:

• Making the efforts of each person identifiable.

• Increasing the pressure to work hard (making group members committed to successful task performance).

• Increasing the apparent importance or value of a task.

• Making people feel that their individual contribution is important.

• Strengthening group cohesiveness which increases the motivation for successful group outcome.

Group Polarisation

We all know that important decisions are taken by groups and not by individuals alone. For example, a decision is to be taken whether a school has to be established in a village. Such a decision has to be a group decision. We have also seen that when groups take decisions, there is a fear that the phenomenon of groupthink may sometimes occur (see Box 7.1). Groups show another tendency referred to as ‘group polarisation’. It has been found that groups are more likely to take extreme decisions than individuals alone. Suppose there is an employee who has been caught taking bribe or engaging in some other unethical act. Her/his colleagues are asked to decide on what punishment s/he should be given. They may let her/him go scot-free or decide to terminate her/his services instead of imposing a punishment which may be commensurate with the unethical act s/he had engaged in. Whatever the initial position in the group, this position becomes much stronger as a result of discussions in the group. This strengthening of the group’s initial position as a result of group interaction and discussion is referred to as group polarisation. This may sometimes have dangerous repercussions as groups may take extreme positions, i.e. from very weak to very strong decisions.

Why does group polarisation occur? Let us take an example whether capital punishment should be there. Suppose you favour capital punishment for heinous crimes, what would happen if you were interacting with and discussing this issue with like-minded people? After this interaction, your views may become stronger. This firm conviction is because of the following three reasons:

• In the company of like-minded people, you are likely to hear newer arguments favouring your viewpoints. This will make you more favourable towards capital punishment.

• When you find others also favouring capital punishment, you feel that this view is validated by the public. This is a sort of bandwagon effect.

• When you find people having similar views, you are likely to perceive them as ingroup. You start identifying with the group, begin showing conformity, and as a consequence your views become strengthened.

Activity 7.3

Assessing Polarisation

Give the class a short, 5-item attitude scale developed by your teacher to assess attitudes towards capital punishment. Based on their responses, divide the class into two groups, i.e. those pro-capital punishment and those anti-capital punishment. Now seat these groups into two different rooms and ask them to discuss a recent case in which death sentence has been given by the court. See how the discussion proceeds in the two groups. After the discussion, re-administer the attitude scale to the group members. Examine if, in both groups, positions have hardened in comparison to their initial position as a result of group discussion.

Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

Groups and individuals exert influence on us. This influence may force us to change our behaviours in a particular direction. The term ‘social influence’ refers to those processes whereby our attitudes and behaviours are influenced by the real or imagined presence of other people. Throughout the day you may encounter a number of situations where others have tried to influence you and make you think in ways they want. Your parents, teachers, friends, radio and television commercials create one or the other kind of social influence. Social influence is a part of our life. In some situations, social influence on us is very strong as a result of which we tend to do things which we otherwise would have not done. On other occasions, we are able to defy influence of others and may even influence them to adopt our own viewpoint. This section describes three important group influence processes, i.e. conformity, compliance and obedience.

Imagine the following situation in your school. Some of your friends come to you with a letter of protest against a rule that has been recently announced, i.e. banning use of mobile phones in the school. Personally you believe that the rule is very sensible and should be enforced. But you also know that if you do not sign the letter, you will lose many friends and get a bad name for not keeping ‘student unity’. What would you do in such a situation? What do you think most people of your age would do? If your answer is that you would agree to sign the letter, you have expressed a form of social influence called ‘conformity’ which means behaving according to the group norm, i.e. the expectations of other group members. Persons who do not conform (called ‘deviants’ or ‘non-conformists’) get noticed more than those who do conform.

Kelman distinguished three forms of social influence, viz. compliance, identification, and internalisation. In compliance, there are external conditions that force the individual to accept the influence of the significant other. Compliance also refers to behaving in a particular way in response to a request made by someone. Thus, in the example described above, you may sign the letter with the thought that you were accepting the request, not because you agree with other students, but because you have been requested to do so by a significant member. This would be a case of compliance also called ‘external/public conformity’. Compliance could take place even without a norm. For example, a member of a community group for ‘clean environment’ requests you to put a sticker on your bike that reads, ‘Say No to Plastic Bags’. You agree to do so, not because of a group norm, or even because you personally believe in banning plastic bags, but because you see no harm or problem in putting such a sticker on your bike. At the same time, you find it easier to say ‘yes’ rather than ‘no’ to such a harmless (and eventually meaningful) request. Identification, according to Kelman, refers to influence process based on agreement-seeking or identity-seeking. Internalisation, on the other hand, is a process based on information-seeking.

Yet another form of behaviour is ‘obedience’. A distinguishing feature of obedience is that such behaviour is a response to a person in authority. In the example given above, you may sign the letter more readily if a senior teacher or a student leader asks you to do so. In such a situation, you are not necessarily following a group norm but rather carrying out an instruction or an order. The presence of an authority figure immediately makes this behaviour different from conformity. For instance, you may stop talking loudly in the classroom when the teacher asks you to keep quiet, but not when your classmate tells you to do the same thing.

We can see that there are some similarities between conformity, compliance, and obedience, but there are also some differences. All three indicate the influence of others on an individual’s behaviour. Obedience is the most direct and explicit form of social influence, whereas compliance is less direct than obedience because someone has requested and thus you comply (here, the probability of refusal is there). Conformity is the most indirect form (you are conforming because you do not want to deviate from the norm).

Conformity

It seems that the tendency to follow a norm is natural, and does not need any special explanation. Yet, we need to understand why such a tendency appears to be natural or spontaneous. First,

norms represent a set of unwritten and informal ‘rules’ of behaviour that provide information to members of a group about what is expected of them in specific situations. This makes the whole situation clearer, and allows both the individual and the group to function more smoothly. Second, in general, people feel un-comfortable if they are considered ‘different’ from others. Behaving in a way that differs from the expected form of behaviour may lead to disapproval or dislike by others, which is a form of social punishment. This is something that most people fear, often in an imagined way. Recall the question we ask so often: “What will people (‘then’) say?” Following the norm is, thus, the simplest way of avoiding disapproval and obtaining approval from others. Third, the norm is seen as reflecting the views and beliefs of the majority. Most people believe that the majority is more likely to be right rather than wrong. An instance of this is often observed in quiz shows on television. When a contestant is at a loss for the correct answer to a question, s/he may opt for an audience opinion, the person most often tends to choose the same option that the majority of the audience chooses. By the same reasoning, people conform to the norm because they believe that the majority must be right.

The pioneering experiments on conformity were carried out by Sherif and Asch. They illustrate some of the conditions that determine the extent of conformity, and also methods that may be adopted for the study of conformity in groups. These experiments demonstrate what Sherif called the ‘autokinetic effect’ (Box 7.3) and the ‘Asch technique’ (Box 7.4).

What lessons are to be learned from the results of these experiments on conformity? The main lesson is that the degree of conformity among the group members is determined by many factors which are situation-specific.

Box 7.3

The Autokinetic Effect

Sherif conducted a series of experiments to demonstrate how groups form their norms, and members make their judgments according to these norms.

Participants were seated in a darkroom, and asked to concentrate on a point of light. After watching this point of light, each person was asked to estimate the distance through which the point had moved. This kind of judgment had to be made over a number of trials. After each trial, the group was given information about the average distance judged by the members. It was observed that on subsequent trials, subjects modified their judgments in a way that made them more similar to the group average. The interesting aspect of this experiment was that the point of light actually did not move at all. The light was only seen as moving by the participant (therefore, the effect has been called the ‘autokinetic effect’). Yet in response to instructions from the experimenter, the participants not only judged the distance the light moved, but also created a norm for this distance. Note that the participants were not given any information regarding the nature of change, if any, in their judgments over trials.

Determinants of Conformity

(i) Size of the group : Conformity is greater when the group is small than when the group is large. Why does it happen? It is easier for a deviant member (one who does not conform) to be noticed in a small group. However, in a large group, if there is strong agreement among most of the members, this makes the majority stronger, and therefore, the norm is also stronger. In such a case, the minority member(s) would be more likely to conform because the group pressure would be stronger.

(ii) Size of the minority : Take the case of the Asch experiment (see Box 7.4). Suppose the subject finds that after some rounds of judgment of the lines, there is another participant who starts agreeing with the subject’s answer. Would the subject now be more likely to conform, or less likely to do so? When the dissenting or deviating minority size increases, the likelihood of conformity decreases. In fact, it may increase the number of dissenters or non-conformists in the group.

(iii) Nature of the task : In Asch’s experiment, the task required an answer that could be verified, and could be correct or incorrect. Suppose the task involves giving an opinion about some topic. In such a case, there is no correct or incorrect answer. In which situation is there likely to be more conformity, the first one where there is something like a correct or an incorrect answer, or the second one where answers can vary widely without any answer being correct or incorrect? You may have guessed right; conformity would be less likely in the second situation.

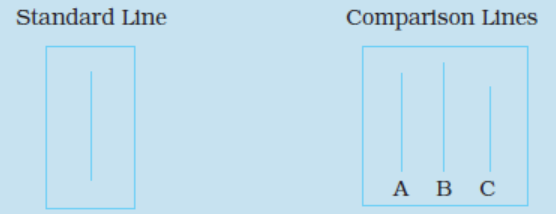

Box 7.4

Group Pressure and Conformity : The Asch Experiment

Asch examined how much conformity there would be when one member of a group experiences pressure from the rest of the group to behave in a specific way, or to give a particular judgment. A group of seven persons participated in an experiment that was a ‘vision test’. There was actually only one true subject. The other six participants were associates of the experimenter, or ‘confederates’ as they are called in social psychology. These confederates were given instructions to give specific responses. Of course, this was not known to the true subject. All participants were shown a vertical line (standard line) that had to be compared with three vertical lines of different lengths, A, B, and C (comparison lines). Participants had to state which of the comparison lines, A, B, or C, was equal to the standard line.

When the experiment began, each participant, by turn, announced her/his answer. The first five persons gave wrong answers (as they had been instructed to do so). The true subject’s turn came last-but-one in each round. So the true subject had the experience of 5 persons giving incorrect answers before her/him. The last person (also a confederate) gave the same incorrect answer as the first five persons. Even if the true subject felt that these answers were incorrect, a norm had been presented to her/him. There were twelve trials. Did the true subject conform to the majority answer, or did s/he give her/his own judgments ?

It was observed that 67 per cent subjects showed conformity, and gave the same incorrect answer as the majority. Remember that this was a situation in which the answers were to be given publicly.

(iv) Public or private expression of behaviour : In the Asch technique, the group members are asked to give their answers publicly, i.e. all members know who has given which response. However, there can be other situations (for example, voting by secret ballot) in which the behaviour of members is private (not known to others). Less conformity is found under private expression than it is seen under public expression.

(v) Personality : The conditions described above show how the features of the situation are important in determining the degree of conformity shown. We also find that some individuals have a conforming personality. Such persons have a tendency to change their behaviour according to what others say or do in most situations. By contrast, there are individuals who are independent, and do not look for a norm in order to decide how to behave in a specific situation. Research has shown that highly intelligent people, those who are confident of themselves, those who are strongly committed and have a high self-esteem are less likely to conform.

Conformity takes place because of informational influence, i.e. influence that results from accepting evidence rather than reality. This kind of rational conformity can be thought of as learning about the world from the actions of others. We learn by observing people, who are the best source of information about many social conventions. New group members learn about the group’s customs by observing the actions of other group members. Conformity may also occur because of normative influence, i.e. influence based on a person’s desire to be accepted or admired by others. In such cases, people conform because deviation from group may lead to rejection or at the least, non-acceptance of some form of punishment. It is generally observed that the group majority determines the final decision, but in certain conditions, a minority may be more influential. This occurs when the minority takes a firm and uncompromising stand, thereby creating a doubt on the correctness of the majority’s viewpoint. This creates a conflict within the group (see Box 7.4).

Compliance

It was stated earlier that compliance refers simply to behaving in response to a request from another person or group even in the absence of a norm. A good example of compliance is the kind of behaviour shown when a salesperson comes to our door. Very often, this person comes with some goods that we really do not wish to buy. Yet, sometimes to our own surprise, we find that the salesperson has spoken to us for a few minutes and the conversation has ended with a purchase of what he or she wished to sell. So why do people comply?

In many situations, this happens because it is an easy way out of the situation. It is more polite and the other party is pleased. In other situations, there could be other factors at work. The following techniques have been found to work when someone wants another person to comply.

• The foot-in-the-door technique : The person begins by making a small request that the other person is not likely to refuse. Once the other person carries out the request, a bigger request is made. Simply because the other person has already complied with the smaller request, he or she may feel uncomfortable refusing the second request. For example, someone may come to us on behalf of a group and give us a gift (something free), saying that it is for promotion. Soon afterwards, another member of the same group may come to us again, and ask us to buy a product made by the group.

• The door-in-the-face technique : In this technique, you begin with a large request and when this is refused a later request for something smaller, the one that was actually desired, is made, which is usually granted by the person.

Obedience

Why do people obey even when they know that their behaviour is harming others? Psychologists have identified several reasons for this. Some of these reasons are :

• People obey because they feel that they are not responsible for their own actions, they are simply carrying out orders from the authority.

• Authority generally possesses symbols of status (e.g., uniform, title) which people find difficult to resist.

• Authority gradually increases commands from lesser to greater levels and initial obedience binds the followers for commitment. Once you obey small orders, slowly there is an escalation of commitment for the person who is in authority and one starts obeying bigger orders.

• Many times, events are moving at such a fast speed, for example in a riot situation, that one has no time to think, just obey orders from above.

Activity 7.4

Demonstrating Obedience in Daily Life

Do you believe the results of Milgram studies on obedience to authority? See for yourself whether obedience occurs or not.

Take permission from your teacher to go to one of the junior classes. Go and make a series of requests to the students. Some examples of such requests are :

Ask students to change their seats with another student.

Ask students to croak like a frog.

Ask students to say ‘jai hind’.

Ask students to put their hands up.

(Feel free to add your own ideas)

What did you see? Did students obey you? Ask them why they did so? Explain to them that you were studying why we obey seniors. Come back and discuss what you saw in the class with your teacher and classmates.

Cooperation and Competition

People interact with each other in different contexts. Behaviours in most social situations are characterised by either ‘cooperation’ or ‘competition’. When groups work together to achieve shared goals, we refer to it as cooperation. The rewards in cooperative situations are group rewards and not individual rewards. However, when members try to maximise their own benefits and work for the realisation of self-interest, competition is likely to result. Social groups may have both competitive as well as cooperative goals. Competitive goals are set in such a way that each individual can get her/his goal only if others do not attain their goals. For example, you can come first in a competition only if others do not perform to such a level that they can be judged as first. A cooperative goal, on the other hand, is one in which each individual can attain the goal only if other members of the group also attain the goal. Let us try to understand this from an example from athletics. In a hundred metres race between six people, only one can be the winner. Success depends on individual performance. In a relay race, victory depends on the collective performance of all members of a team. Deutsch investigated cooperation and competition within groups. College students were assigned to groups of five persons and were required to solve puzzles and problems. One set of groups, referred to as the ‘cooperative group’, were told that they would be rewarded collectively for their performance. The other set of groups, labelled as ‘competitive group’ were told that there was a reward for individual excellence. Results showed that in cooperative groups, there was more coordination, there was acceptance for each other’s ideas, and members were more friendly than those in the competitive group. The main concern of the members of the cooperative group was to see that the group excels.

Although competition between individuals within a group may result in conflict and disharmony, competition between groups may increase within group cohesion and solidarity.

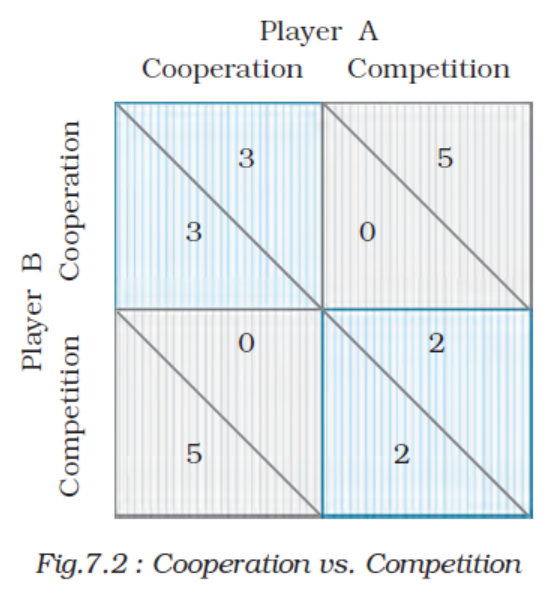

Prisoner’s Dilemma Game, which is a two person game in which both parties are faced with cooperation or competition, and depending upon their choices both can win or lose, is often used to study cooperation or competition. This game is based on an anecdote. Two suspects were quizzed by detectives separately. The detectives had only enough evidence to convict them for a small offence. Separately the two convicts were offered a chance to confess. If one confesses and the other does not, the one who confesses will get no punishment and her/his confession will be used to convict the other with a serious offence. If both confess, the punishment to both will be mild. If neither confesses, each will receive a light sentence. This game has been used in hundreds of experiments to demonstrate that when two parties are involved, there is a conflict between motive to cooperate and motive to compete (see Figure 7.2).

Sherif’s Summer Camp Experiments : A Journey from Ingroup Formation to Intergroup Competition and Finally Intergroup Cooperation

Sherif conducted a series of experiments on 11–12 year old boys who did not know each other. The boys were attending a summer camp. Unknown to the boys, there were researchers in the camp who examined their (the boys) behaviour. The experiment consisted of four phases, viz. friendship formation, group formation, intergroup competition, and intergroup cooperation.

• Friendship formation : When the boys arrived at the camp, they spent their initial time together. They mixed freely with each other and chose their friends for games and other activities.

• Ingroup formation : The boys were then divided into two groups by the experimenter. The boys belonging to the two groups lived separately. Members within the group engaged in cooperative projects to increase cohesiveness. The groups were given separate names. Over time, they developed their own norms.

• Intergroup competition : The two groups were brought together in several competitive situations. Matches were organised in which the groups competed against each other. This competition brought in tension and hostility against each other as a group; so much so that the groups started calling each other names. At the same time, ingroup cohesion and loyalty became stronger.

• Intergroup cooperation : To reduce the hostility generated by intergroup competition, the researchers created a problem which affected both the groups, and both groups wanted to solve them. Superordinate goals could be achieved only through cooperation between the groups. The water supply of both groups was disrupted. Members of both groups helped each other to overcome this. This intergroup cooperation phase reduced the hostility. This resulted in the development of a superordinate goal, i.e. a goal to which personal goals were subordinated.

This research is important as it showed that antagonistic and hostile behaviour can be generated by group situations. At the same time, it shows that hostility between groups can be reduced by focusing on superordinate goals, which are important and beneficial to both groups alike.

For example, there are two players, A and B. If both cooperate, both get three points each. If player A competes and wins, s/he gets 5 points and B gets 0 points. If B competes and wins s/he gets 5 points and A gets 0 points. If both A and B compete, both get two points each. What outcomes do you expect? Why do you expect so? Give reasons.

Determinants of Cooperation and Competition

What factors determine whether people will cooperate or compete? Some of the important ones are given below:

(i) Reward structure : Psychologists believe that whether people will co-operate or compete will depend on the reward structure. Cooperative reward structure is one in which there is promotive interdependence. Each is beneficiary of the reward and reward is possible only if all contribute. A competitive reward structure is one in which one can get a reward only if others do not get it.

(ii) Interpersonal communication : When there is good interpersonal communication, then cooperation is the likely consequence. Communication facilitates interaction, and discussion. As a result, group members can convince each other and learn about each other.

(iii) Reciprocity : Reciprocity means that people feel obliged to return what they get. Initial cooperation may encourage more cooperation. Competition may provoke more competition. If someone helps, you feel like helping that person; on the other hand, if someone refuses to help you when you need help, you would not like to help that person also.

Social Identity

Have you ever asked the question “who am I?” What was your answer to this question? Probably your answer was that you are a hard-working, happy-go-lucky girl/boy. This answer tells you about your social identity which is one’s self-definition of who s/he is. This self-definition may include both personal attributes, e.g. hard working, happy-go-lucky, or attributes which you share with others, e.g. girl or boy. Although some aspects of our identity are determined by physical characteristics, we may acquire other aspects as a consequence of our interaction with others in society. Sometimes we perceive ourselves as unique individuals and at other times we perceive ourselves as members of groups. Both are equally valid expressions of self. Our personal identities derived from views of oneself as a unique individual, and social identities derived from groups we perceive ourselves to be members of, are both important to us. The extent to which we define ourselves either at personal or at social levels is flexible. From your own experience, you would realise that identification with social groups can have a great deal of importance for your self-concept. How do you feel when India wins a cricket match? You feel elated and proud. You feel so because of your social identity as an Indian. Social identity is, thus, that aspect of our self-concept which is based on our group membership. Social identity places us, i.e. tells us what and where we are in the larger social context, and thus helps us to locate ourselves in society. You have a social identity of a student of your school. Once you have this identity of a student of your school, you internalise the values emphasised in your school and make these values your own. You strive to fulfil the motto of your school. Social identity provides members with a shared set of values, beliefs and goals about themselves and about their social world. Once you internalise the values of your school, this helps to coordinate and regulate your attitudes and behaviour. You work hard for your school to make it the best school in your city/state. When we develop a strong identity with our own group, the categorisation as ingroup and outgroup becomes salient. The group with which you identify yourself becomes the ingroup and others become the outgroup. The negative aspect of this own group and outgroup categorisation is that we start showing favouritism towards our ingroup by rating it more favourably in comparison to the outgroup, and begin devaluating the outgroup. This devaluation of the outgroup is the basis of a number of intergroup conflicts.

Intergroup Conflict : Nature and Causes

Conflict is a process in which either an individual or a group perceives that others (individual or group) have opposing interests, and both try to contradict each other. There is this intense feeling of ‘we’ and ‘other’ (also referred to as ‘they’). There is also a belief by both parties that the other will protect only its own interests; their (the other side’s) interests will, therefore, not be protected. There is not only opposition of each other, but they also try to exert power on each other. Groups have been found to be more aggressive than individuals. This often leads to escalation of conflict. All conflicts are costly as there is a human price for them. In wars, there are both victories and defeats, but the human cost of war is far beyond all this. Various types of conflict are commonly seen in society, which turn out to be costly for both sides as well as for society.

• One major reason is lack of communication and faulty communi-cation by both parties. This kind of communication leads to suspicion, i.e. there is a lack of trust. Hence, conflict results.

• Another reason for intergroup conflict is relative deprivation. It arises when members of a group compare themselves with members of another group, and perceive that they do not have what they desire to have, which the other group has. In other words, they feel that they are not doing well in comparison to other groups. This may lead to feelings of deprivation and discontentment, which may trigger off conflict.

• Another cause of conflict is one party’s belief that it is better than the other, and what it is saying should be done. When this does not happen, both parties start accusing each other. One may often witness a tendency to magnify even smaller differences, thereby conflict gets escalated because every member wants to respect the norms of her/his group.

• A feeling that the other group does not respect the norms of my group, and actually violates those norms because of a malevolent intent.

• Desire for retaliation for some harm done in the past could be another reason for conflict.

• Biased perceptions are at the root of most conflicts. As already mentioned earlier, feelings of ‘they’ and ‘we’ lead to biased perceptions.

• Research has shown that when acting in groups, people are more competitive as well as more aggressive than when they are on their own. Groups compete over scarce resources, both material resources, e.g. territory, and money as well as social resources, e.g. respect and esteem.

But, if you contribute more and get less, you are likely to feel irritated and exploited.

Conflicts between groups give impetus to a series of social and cognitive processes. These processes harden the stand of each side leading to ingroup polarisation. This may result in coalition formation of like-minded parties, thereby increasing the apprehensions of both parties resulting in misperceptions, and biased interpretations and attributions. The result is increased conflict. Present-day society is fraught with various intergroup conflicts. These are related to caste, class, religion, region, language, just to name a few of them. Gardner Murphy wrote a book entitled ‘In the Minds of Men’. Most conflicts begin in the minds of men and then go to the field. Explanations of such conflicts can be at the structural, group, and individual levels. Structural conditions include high rates of poverty, economic and social stratification, inequality, limited political and social opportunity, etc. Research on group level factors has shown that social identity, realistic conflict between groups over resources, and unequal power relations between groups lead to escalation of conflict. At the individual level, beliefs, biased attitudes, and personality characteristics are important determinants. It has been found that at the individual level, there is a progression along a continuum of violence. Very small acts that initially may have no significance, like calling the other group a name, may lead to psychological changes that make further destructive actions possible.

Deutsch identified the following consequences of intergroup conflict.

• Communication between the groups becomes poor. The groups do not trust each other, thereby leading to a breakdown in communication and this generates suspicion for each other.

• Groups start magnifying their differences and start perceiving their behaviour as fair and the other’s behaviour as unfair.

• Each side tries to increase its own power and legitimacy. As a conse-quence, the conflict gets escalated shifting from few specific issues to much larger issues.

• Once conflict starts, several other factors lead to escalation of conflict. Hardening of ingroup opinion, explicit threats directed at the outgroup, each group retaliating more and more, and other parties also choosing to take sides lead to escalation of conflict.

Conflict Resolution Strategies

Conflicts can be reduced if we know about their causes. The processes that increase conflict can be turned around to reduce it also. A number of strategies have been suggested by psychologists. Some of these are :

Introduction of superordinate goals : Sherif’s study, already mentioned in the section on cooperation and competition, showed that by introducing superordinate goals, intergroup conflict can be reduced. A superordinate goal is mutually beneficial to both parties, hence both groups work cooperatively.

Altering perceptions : Conflicts can also be reduced by altering perceptions and reactions through persuasion, educational and media appeals, and portrayal of groups differently in society. Promoting empathy for others should be taught to everyone right from the beginning.

Increasing intergroup contacts : Conflict can also be reduced by increasing contacts between the groups. This can be done by involving groups in conflict on neutral grounds through community projects and events. The idea is to bring them together so that they become more appreciative of each other’s stand. However, for contacts to be successful, they need to be maintained, which means that they should be supported over a period of time.

Redrawing group boundaries : Another technique that has been suggested by some psychologists is redrawing the group boundaries. This can be done by creating conditions where groups boundaries are redefined and groups come to perceive themselves as belonging to a common group.

Negotiations : Conflict can also be resolved through negotiations and third party interventions. Warring groups can resolve conflict by trying to find mutually acceptable solutions. This requires understanding and trust. Negotiation refers to reciprocal communications so as to reach an agreement in situations in which there is a conflict. Sometimes it is difficult to dissipate conflict through negotiations; at that time mediation and arbitration by a third party is needed. Mediators help both parties to focus their discussions on the relevant issues and reach a voluntary agreement. In arbitration, the third party has the authority to give a decision after hearing both parties.

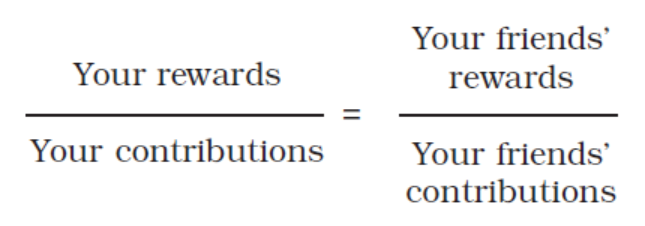

Structural solutions : Conflict can also be reduced by redistributing the societal resources according to principles based on justice. Research on justice has identified several principles of justice. Some of these are : equality (allocating equally to every one), need (allocating on the basis of needs), and equity (allocating on the basis of contributions of members).

Respect for other group’s norms : In a pluralist society like India, it is necessary to respect and be sensitive to the strong norms of various social and ethnic groups. It has been noticed that a number of communal riots between different groups have taken place because of such insensitivity.

Key Terms

Arbitration, Cohesiveness, Competition, Compliance, Conflict, Conformity, Cooperation, Goal achievement, Group, Group formation, Groupthink, Identity, Ingroup, Interdependence, Intergroup, Negotiation, Norms, Obedience, Outgroup, Proximity, Roles, Social facilitation, Social influence, Social inhibition, Social loafing, Status, Structure, Superordinate goals.

Groups are different from other collections of people. Mutual interdependence, roles, status, and expectations are the main characteristics of groups.

• Groups are organised systems of two or more individuals.

• People join groups because they provide security, status, self-esteem, satisfaction of one’s psychological and social needs, goal achievement, and knowledge and information.

• Proximity, similarity, and common motives and goals facilitate group formation.

• Generally, group work leads to beneficial results. However, sometimes in cohesive and homogeneous groups, the phenomenon of groupthink may occur.

• Groups are of different types, i.e. primary and secondary, formal and informal, and ingroup and outgroup.

• Groups influence individual behaviour. Social facilitation and social loafing are two important influences of groups.

• Conformity, compliance, and obedience are three important forms of social influence.

• Conformity is the most indirect form of social influence; obedience the most direct form; compliance is in-between the two.

• People interact in social situations by either cooperating or competing.

• One’s self-definition of who s/he is referred to as social identity.

• Group conflicts occur in all societies.

• Group conflicts can be reduced if we know the causes of such conflicts.

Review Questions

1. Compare and contrast formal and informal groups, and ingroups and outgroups.

2. Are you a member of a certain group? Discuss what motivated you to join that group.

3. How does Tuckman’s stage model help you to understand the formation of groups?

4. How do groups influence our behaviour?

5. How can you reduce social loafing in groups? Think of any two incidents of social loafing in school. How did you overcome it?

6. How often do you show conformity in your behaviour? What are the determinants of conformity?

7. Why do people obey even when they know that their behaviour may be harming others? Explain.

8. What are the benefits of cooperation?

9. How is one’s identity formed?

10. What are some of the causes of intergroup conflict? Think of any international conflict. Reflect on the human price of this conflict.

Project Ideas

1. “S/he who does not ask will never get a bargain.” Collect the newspapers of last one month. List the different bargains that were offered by shopkeepers. What compliance techniques were used by them? Ask your friends how many were attracted by these bargains.

2. Make a list of different conflicts that have occurred among different houses in the school. How were these conflicts resolved?

3. Identify any Test series in cricket which India played recently. Collect the newspapers of that period. Evaluate the reviews of the matches and comments made by Indian and rival commentators. Do you see any difference between the comments?

4. Imagine that you have to collect money to help an NGO working for the girl child. What techniques of social influence would you use? Try any two techniques and see the difference.

Weblinks

http://www.mapnp.org/library/grp_skill/theory/theory.htm

http://www.socialpsychology.org/social.htm

http://www.stanleymilgram.com/main.htm

http://www.psychclassics.yorku.ca/sheriff/chap1.htm

Pedagogical Hints

1. In the topic of nature and formation of groups, students should be made to understand the importance of groups in real-life. Here, it needs to be emphasised that they should be careful in choosing groups. Teachers can ask a few students how they have become members of different groups, and what do they get from membership in these groups.

2. For explaining social loafing, simple experiments can be conducted in the class by asking students to perform some activities in groups and then asking them about their contributions in the activities undertaken. Learning experience for students should be on ways to avoid social loafing.

3. In the topic of cooperation and competition, students should be told the benefits of both cooperation and competition. They should be able to appreciate that cooperation is a better strategy in society. Some cases of real-life where cooperative efforts have been successful can be discussed.

4. Students should be able to appreciate that identities are important and how our identities influence our social behaviour.

5. In the section on intergroup conflict, emphasis should be on conflict resolution strategies rather than conflict per se.