Table of Contents

3

The Story of Indian Democracy

We are all familiar with the idea that democracy is a government of the people, by the people, and for the people. Democracies fall into two basic categories, direct and representative. In a direct democracy, all citizens, without the intermediary of elected or appointed officials, can participate in making public decisions. Such a system is clearly only practical with relatively small numbers of people – in a community organisation or tribal council, for example, the local unit of a trade union, where members can meet in a single room to discuss issues and arrive at decisions by consensus or majority vote.

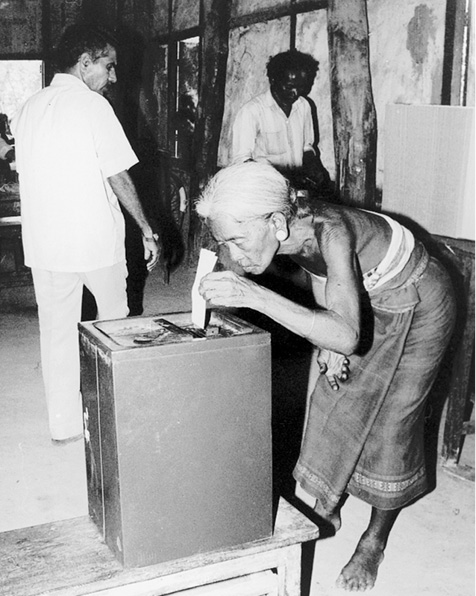

Modern society, with its size and complexity, offers few opportunities for direct democracy. Today, the most common form of democracy, whether for a town of 50,000 or nations of 1 billion, is representative democracy, in which citizens elect officials to make political decisions, formulate laws, and administer programmes for the public good. Ours is a representative democracy. Every citizen has the important right to vote her/his representative. People elect their representatives to all levels from Panchayats, Municipal Boards, State Assemblies and Parliament. There has increasingly been a feeling that democracy ought to involve people more regularly and should not just mean casting a vote every five years. Both the concepts of participatory democracy and decentralised governance have thus become popular. Participatory democracy is a system of democracy in which the members of a group or community participate collectively in the taking of major decisions. This chapter will discuss the panchayati raj system as an example of a major initiative towards decentralised and grassroot democracy.

An old lady voting in election

Both the procedures as well as the values that form Indian democracy have developed over the long years of India’s anti-colonial struggle. In the last 70 years, since Independence, the success of Indian democracy has been seen as a remarkable feat for a country with such great diversity as well as inequality. This chapter cannot possibly provide a comprehensive account of its rich and complex past and present.

In this chapter we, therefore, try and provide only a synoptic view of democracy in India. We first look at the Indian Constitution, the bedrock of Indian democracy. We focus on its key values, briefly look at the making of the Constitution, drawing upon some snippets of the debates representing different views. Second, we look at the grassroot level of functioning democracy, namely the Panchayat Raj system. In both expositions you will notice that there are different groups of people representing competing interest and often also different political parties. This is an essential part of any functioning democracy. The third part of this chapter seeks to discuss how competing interests function, what the terms interest groups and political parties mean and what their role is in a democratic system such as ours.

3.1 The Indian Constitution

The core values of Indian democracy

Like so many other features of modern India we need to begin the story about modern Indian democracy from the colonial period. You have just read about the many structural and cultural changes that British colonialism brought about deliberately. Some of the changes that came about happened in an unintended fashion. The British did not intend to introduce them. For instance, they sought to introduce western education to create a western educated Indian middle class that would help the colonial rulers to continue their rule. A western educated section of Indians did emerge. But, instead of aiding British rule, they used western liberal ideas of democracy, social justice and nationalism to challenge colonial rule.

This should not, however, suggest that democratic values and democratic institutions are purely western. Our ancient epics, our diverse folk tales from one corner of the country to another are full of dialogues, discussions and contrasting positions. Think of any folk tale, riddles, folk song or any story from any epic that reveals different viewpoints? We just draw from one example from the epic Mahabharata.

However, as we saw in chapter 1 and 2 social change in modern India is not just about Indian or western ideas. It is a combination as well as reinterpretation of western and Indian ideas. We saw that in the case of the social reformers. We saw the use of both modern ideas of equality and traditional ideas of justice. Democracy is no exception. In colonial India the undemocratic and discriminatory administrative practice of British colonialism contrasted sharply with the vision of freedom which western theories of democracy espoused and which the western educated Indians read about. The scale of poverty and intensity of social discrimination within India also led to deeper questioning of the meaning of democracy. Is democracy just about political freedom? Or is it also about economic freedom and social justice? Is it also about equal rights to all irrespective of caste, creed, race and gender? And if that is so how can such equality be realised in an unequal society?

BOX 3.1

The tradition of questioning

When, in the Mahabharata, Bhrigu tells Bharadvaja that caste division relates to differences in physical attributes of different human beings, reflected in skin colour, Bharadvaja responds not only by pointing to the considerable variations in skin colour within every caste (‘if different colours indicate different castes, then all castes are mixed castes’), but also by the more profound questions: “We all seem to be affected by desire, anger, fear, sorrow, worry, hunger and 37 BOX 3.1 labour; how do we have caste differences then?

Society has been aiming to lay a new foundation as was summarised by the French revolution in three words, fraternity, liberty and equality. The French Revolution was welcomed because of this slogan. It failed to produce equality. We welcomed the Russian revolution because it aims to produce equality. But it cannot be too much emphasised that in producing equality, society cannot afford to sacrifice fraternity or liberty. Equality will be of no value without fraternity or liberty. It seems that the three can coexist only if one follows the way of the Buddha…

(Ambedkar 1992)

Exercise For Box 3.2

Read the text above and discuss how diverse intellectual ideas from the west and from India were being used to interrogate and construct new models of democracy. Can you think of other reformers and nationalists who were trying to do the same?

Many of these issues were thought of much before India became free. Even as India fought for its independence from British colonialism a vision of what Indian democracy ought to look like emerged. As far back as in 1928, Motilal Nehru and eight other Congress leaders drafted a constitution for India. In 1931, the resolution at the Karachi session of the Indian National Congress dwelt on how independent India’s constitution should look like. The Karachi Resolution reflects a vision of democracy that meant not just formal holding of elections but a substantive reworking of the Indian social structure in order to have a genuine democratic society.

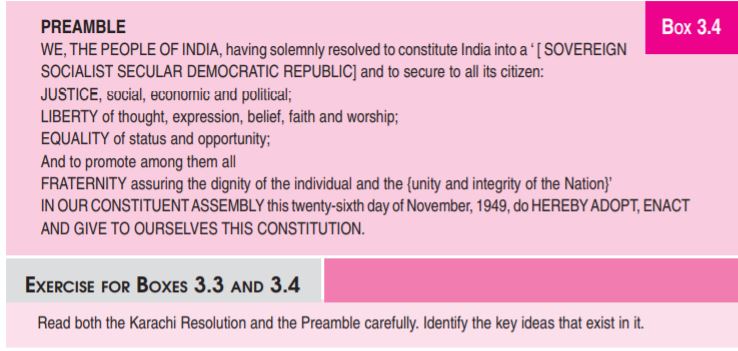

The Karachi Resolution clearly spells out the vision of democracy that the nationalist movement in India had. It articulates the values that were further given full expression in the Indian Constitution. You will notice how the Preamble of the Indian Constitution seeks to ensure not just political justice but also social and economic justice. You will likewise notice that equality is not just about equal political rights but also of status and opportunity.

Appendix No. 6

What Swaraj will Include

Karachi Congress Resolution, 1931

Swaraj as conceived by the Congress should include real economic freedom of the masses. The Congress declares that no constitution will be acceptable to it unless it provides or enables the Swaraj Government to provide for:

1. Freedom of expression, association and meeting.

2. Freedom of religion.

3. Protection of all cultures and languages.

4. All citizens shall be equal before the law.

5. No disability in employment or trade or profession on account of religion, caste or sex.

6. Equal rights and duties for all in regard to public wells, schools, etc.

7. All to have right to bear arms in accordance with regulations.

8. No person to be deprived of property or liberty except in accordance with law.

9. Religious neutrality of State.

10. Adult Suffrage.

11. Free compulsory primary education.

12. No titles to be conferred.

13. Capital punishment to be abolished.

14. Freedom of movement for every citizen of India and right to settle and acquire property

in any part thereof, and equal protection of law.

15. Proper standard of life for industrial workers and suitable machinery for settlement of disputes between employers and workers and protection against old age, sickness, etc.

16. All labour to be free from conditions of serfdom.

17. Special protection of women workers.

18. Children not to be employed in mines and factories.

19. Rights of peasants and workers to form unions.

20. Reform of system of land revenue and tenure and rent, exempting rent and revenue for uneconomical holdings and reduction of dues payable for smaller holdings.

21. Inheritance tax on graduated scale.

22. Reduction of military expenditure by at least half.

23. No servant of State ordinarily to be paid above Rs 500 per month.

24. Abolition of Salt tax.

25. Protection of indigenous cloth against competition of foreign cloth.

26. Total prohibition of intoxicating drinks and drugs.

27. Currency and exchange in national interest.

28. Nationalisation of key industries and services, railways, etc.

29. Relief of agricultural indebtedness and control of usury.

30. Military training for citizens.

Karachi resolution condensed to be printed on membership forms.

Democracy works at many levels. In this chapter we began with the vision of the Indian Constitution for this is the bedrock upon which democracy rests in India. Significantly, the Constitution emerged from intense and open discussions within the Constituent Assembly. Thus, its vision or ideological content as well as the process or procedure by which it was formed was democratic. The next section briefly looks at some of the debates.

Constituent Assembly debates: A history

In 1939, Gandhiji wrote an article in the ‘Harijan’ called ‘The Only Way’ in which he said “… the Constituent Assembly alone can produce a constitution indigenous to the country and truly and fully representing the will of the people” one based on “unadulterated adult franchise for both men and women”. The popular demand in 1939 for a Constituent Assembly was, after several ups and downs conceded by Imperialist Britain in 1945. In July 1946, the elections were held. In August 1946, The Indian National Congress’ Expert Committee moved a resolution in the Constituent Assembly. This contained the declaration that India shall be a Republic where the declared social, economic and political justice will be guaranteed to all the people of India.

On matters of social justice, there were lively debates on whether government functions should be prescribed and the state should be bound down to them. Issues debated ranged from right to employment, to social security, land reforms to property rights, to the organisation of panchayats. Here are some snippets from the debates:

Snippets from the debates

K.T. Shah said that the right to useful employment could and should be made real by a categoric obligation on the part of the state to provide useful work to every citizen who was able and qualified.

B. Das spoke against classifying the functions of the government as justiciable and non justiciable, “I think it is the primary duty of Government to remove hunger and render social justice to every citizen and to secure social security……..”. The teeming millions do not find any hope that the Union Constitution…. will ensure them freedom from hunger, will secure them social justice, will ensure them a minimum standard of living and a minimum standard of public health”

Ambedkar’s answer was as follows: “ The Draft Constitution as framed only provides a machinery for the government of the country. It is not a contrivance to install any particular party in power as has been done in some countries. Who should be in power is left to be determined by the people, as it must be, if the system is to satisfy the tests of democracy. But whoever captures power will not be free to do what he likes with it. In the exercise of it, he will have to respect these Instruments of Instructions which are called Directive Principles. He cannot ignore them. He may not have to answer for their breach in a court of law. But he will certainly have to answer for them before the electorate at election time. What great value these directive principles possess will be realised better when the forces of right contrive to capture power.”

On land reform Nehru said, that the social forces were such that law could not stand in the way of reform, an interesting reflection on the dynamics between the two. “If law and Parliaments do not fit themselves into the changing picture, they cannot control the situation”.

On the protection of the tribal people and their interests, leaders like Jaipal Singh were assured by Nehru in the following words during the Constituent Assembly debates: “It is our intention and our fixed desire to help them as possible; in as efficient a way as possible to protect them from possibly their rapacious neighbours occasionally and to make them advance”

Even as the Constituent Assembly adopted the title Directive Principles of State Policy to the rights that courts could not enforce, additional principles were added with unanimous acceptance. These included K. Santhanam’s clause that the state shall organise village panchayats and endow them with the powers and authority to be effective units of local self government.

T. A. Ramalingam Chettiar added the clause for promotion of cottage industries on co-operative lines in rural areas. Veteran parlimentarian Thakurdas Bhargava added that the state should organise agriculture and animal husbandry on modern lines.

EXERCISE FOR BOX 3.5

Read the above snippets of the debates carefully. Discuss how different concerns were being expressed and debated. How relevant are these issues today?

Competing Interests: the Constitution and Social Change

India exists at so many levels. The multi-religious and multicultural composition of the population with distinct streams of tribal culture is one aspect of the plurality. Many divides classify the Indian people. The impact that culture, religion, and caste have on the urban–rural divide, rich-poor divide and the literate-illiterate divide is varied. Deeply stratified by caste and poverty, there are groupings and sub-groupings among the rural poor. The urban working class comprises a very wide range. Then, there is the well-organised domestic business class as also the professional and commercial class. The urban professional class is highly vocal. Competing interests operate on the Indian social scene and clamour for control of the State’s resources.

However, there are some basic objectives laid down in the Constitution and which are generally agreed in the Indian political world as being obviously just. These would be empowerment of the poor and marginalised, poverty alleviation, ending of caste and positive steps to treat all groups equally.

Competing interests do not always reflect a clear class divide. Take the issue of the close down of a factory because it emits toxic waste and affects the health of those around. This is a matter of life, which the Constitution protects. The flipside is that the closure will render people jobless. Livelihood again, is a matter of life that the Constitution protects. It is interesting that at the time of drawing up the Constitution, the Constituent Assembly was fully aware of this complexity and plurality but was intent on securing social justice as a guarantee.

Constitutional norms and social justice: interpretation to aid social justice

It is useful to understand that there is a difference between law and justice. The essence of law is its force. Law is law because it carries the means to coerce or force obedience. The power of the state is behind it. The essence of justice is fairness. Any system of laws functions through a hierarchy of authorities. The basic norm from which all other rules and authorities flow is called the Constitution. It is the document that constitutes a nation’s tenets. The Indian Constitution is India’s basic norm. All other laws are made as per the procedures the Constitution prescribes. These laws are made and implemented by the authorities specified by the Constitution. A hierarchy of courts (which too are authorities created by the Constitution) interpret the laws when there is a dispute. The Supreme Court is the highest court and the ultimate interpreter of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court has enhanced the substance of Fundamental Rights in the Constitution in many important ways. The Box below illustrates a few instances.

Box 3.6

A Fundamental Right includes all that is incidental to it. The terse words of Article 21 recognising the right to life and liberty have been interpreted as including all that goes into a life of quality, including livelihood, health, shelter, education and dignity. In various pronouncements different attributes of ‘life’ have been expanded and ‘life’ has been explained to mean more than mere animal existence. These interpretations have been used to provide relief to prisoners subjected to torture and deprivation, release and rehabilitation of bonded labourers, against environmentally degrading activities, to provide primary health care and primary education.

In 1993 the Supreme Court held that Right to Information is part of and incidental to the Right to Expression under Article 19(1) (a).

Reading Directive Principles into the content of Fundamental Rights. The Supreme Court read the Directive Principle of “equal pay for equal work” into the Fundamental Right to Equality under Article 14 and has provided relief to many plantation and agricultural labourers and to others.

The Constitution is not just a ready referencer of do’s and don’ts for social justice. It has the potential for the meaning of social justice to be extended. Social movements have also aided the Courts and authorities to interpret the contents of rights and principles in keeping with the contemporary understanding on social justice. Law and Courts are sites where competing views are debated. The Constitution remains a means to channelise and civilise political power towards social welfare.

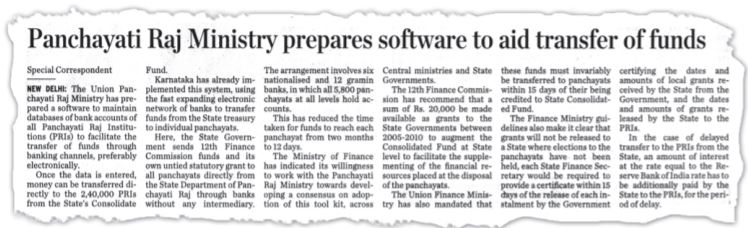

You will realise that the Constitution has the capacity to help people because it is based on basic norms of social justice. For instance, the Directive Principle on village panchayats was moved as an amendment in the Constituent assembly by K. Santhanam. After forty odd years it became a Constitutional imperative after the 73rd Amendment in 1992. You shall be dealing with this in the next section.

3.2 The Panchayati Raj and the challenges of rural social transformation

Ideals of Panchayati Raj

Panchayati Raj translates literally to ‘Governance by five individuals’. The idea is to ensure at the village or grass root level a functioning and vibrant democracy. While the idea of grassroot democracy is not an alien import to our country, in a society where there are sharp inequalities democratic participation is hindered on grounds of gender, caste and class. Furthermore, as you shall see in the newspaper reports later in the chapter, traditionally there have been caste panchayats in villages. But they have usually represented dominant groups. Furthermore, they often held conservative views and often have, and continue to take decisions that go against both democratic norms and procedures.

The three-tier system of Panchayati Raj Institution

The structure is like a pyramid. At the base of the structure stands the unit of democracy or Gram Sabha. This consists of the entire body of citizens in a village or grama. It is this general body that elects the local government and charges it with specific responsibilities. The Gram Sabhas ideally ought to provide an open forum for discussions and village-level development activities and play a crucial role in ensuring inclusion of the weaker sections in the decision-making processes.

The 73rd Amendment provided a three-tier system of Panchayati Raj for all states having a population of over twenty lakhs.

It became mandatory that election to these bodies be conducted every five years.

It provided reservation of seats for the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and thirty three percent seats for women.

It constituted District Planning Committee to prepare drafts and develop plans for the district as a whole.

When the constitution was being drafted panchayats did not find a mention in it. At this juncture, a number of members expressed their sorrow, anger and disappointment over this issue. At the same time, drawing on his own rural experience Dr. Ambedkar argued that local elites and upper castes were so well entrenched in society that local self-government only meant a continuing exploitation of the downtrodden masses of Indian society. The upper castes would no doubt silence this segment of the population further. The concept of local government was dear to Gandhiji too. He envisaged each village as a self-sufficient unit conducting its own affairs and saw gram-swarajya to be an ideal model to be continued after independence.

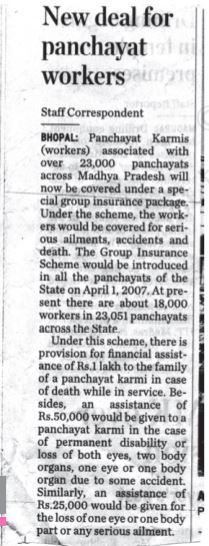

It was, however, only in 1992 that grassroot democracy or decentralised governance was ushered in by the 73rd Constitutional Amendment. This act provided constitutional status to the Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs). It is compulsory now for local self-government bodies in rural and municipal areas to be elected every five years. More importantly, control of local resources is given to the elected local bodies.

The 73rd and 74th amendments to the Constitution ensured the reservation of one third of the total seats for women in all elected offices of local bodies in both the rural and urban areas. Out of this, 17 per cent seats are reserved for women belonging to the scheduled castes and tribes. This amendment is significant as for the first time it brought women into elected bodies which also bestowed on them decision making powers. One third of the seats in local bodies, gram panchayats, village panchayats, municipalities, city corporations and district boards are reserved for women. The 1993-94 elections, soon after the 73rd amendment brought in 800,000 women into the political processes in a single election. That was a big step indeed in enfranchising women. A constitutional amendment prescribed a three-tier system of local self-governance (read box 3.7 on the last page) for the entire country, effective since 1992-93.

Powers and Responsibilities of Panchayats

According to the Constitution, Panchayats should be given powers and authority to function as institutions of self-government. It, thus, requires all state governments to revitalise local representative institutions.

The following powers and responsibility were delegated to the Panchayats:

to prepare plans and schemes for economic development

to promote schemes that will enhance social justice

to levy, collect and appropriate taxes, duties, tolls and fees

help in the devolution of governmental responsibilities, especially that of finances to local authorities

Social welfare responsibilities of the Panchayats include the maintenance of burning and burial grounds, recording statistics of births and deaths, establishment of child welfare and maternity centres, control of cattle pounds, propagation of family planning and promotion of agricultural activities. The development activities include the construction of roads, public buildings, wells, tanks and schools. They also promote small cottage industries and take care of minor irrigation works. Many government schemes like the Integrated Rural Development Programme (IRDP) and Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) are monitored by members of the panchayat.

The main income of the Panchayats is from tax levied on property, profession, animals, vehicles, cess on land revenue and rentals. The resources are further increased by the grants received through the Zilla Panchayat. It is also considered compulsory for Panchayat offices to put up boards outside their offices, listing the break up of funds received, and utilisation of the financial aid received. This exercise was taken up to ensure that people at the grassroot level should have the ‘right to information’ – opening all functioning to the public eye. People had the right to scrutinise allocation of money. And ask reasons for decisions that were taken for the welfare and development activities of the village.

Nyaya Panchayats have been constituted in some states. They possess the authority to hear some petty, civil and criminal cases. They can impose fines but cannot award a sentence. These village courts have often been successful in bringing about an agreement amongst contending parties. They have been particularly effective in punishing men who harass women for dowry and perpetrate violence against them.

Panchayati Raj in Tribal Areas

Van Panchayats

In Uttarakhand, women do most of the work since the men are often posted far away in defence services. Most of the villagers are still dependent on firewood for cooking. As you may know, deforestation is a big problem in the mountainous regions. Women sometimes walk many miles to collect firewood and fodder for their animals. To overcome this problem, women have set up van-panchayats. Members of the van-panchayats develop nurseries and nurture tree saplings for planting on the hill slopes. Members also police nearby forests to keep an eye on illegal felling of trees. The Chipko movement, where women hugged trees to prevent them from being cut, had its beginnings in this area.

Panchayati Raj training for illiterate women

Innovative modes of communicating the strength of the Panchyat Raj system

The story of two villages, Sukhipur and Dhukipur are unravelled through a cloth ‘phad’ or a scroll (a traditional folk medium of story telling). Village Dhukipur (sad village) has a corrupt Pradhan (Bimla), who has spent the money received from the panchayat for building a school, on constructing a house for herself and her family. The rest of the village are sad and poor. On the other hand Sukhipur (happy village) has a content populace as the Pradhan (Najma) has invested rural reconstruction money in developing good infrastructure for her village. Here the primary health centre is functioning, it has a ‘pucca’ building and also has a good road so that buses can reach the village.

Pictorial pictures on the ‘phad’, accompanied with folk music were useful tools to convey the message for able governance and participation. This innovative method of story telling was very affective in bringing awareness to unlettered women. Most importantly the campaign conveyed the message, that it was not enough to merely vote, or to stand for election, or to win. But important to know why one is voting for a particular person, what are the traits to look for, and what does he or she stand for .The value for integrity is also emphasised through the story and song media of the ‘phad’.

This training programme was conducted by Mahila Samakhya an NGO working towards Rural Women’s Empowerment.

Many tribal areas have had a rich tradition of grassroot democratic functioning. We give an illustrative example from Meghalaya. All the three major ethnic tribal groups, namely, the Khasis, Jaintias and the Garos have their own traditional political institutions that have existed for hundreds of years. These political institutions were fairly well-developed and functioned at various tiers, such as the village level, clan level and state level. For instance, in the traditional political system of the Khasis each clan had its own council known as the ‘Durbar Kur’ which was presided over by the clan headman. Though there is a long tradition of grassroot political institutions in Meghalaya, a large chunk of tribal areas lie outside the provisions of the 73rd Amendment. This may be because the concerned policy makers did not wish to interfere with the traditional tribal institutions.

However, as sociologist Tiplut Nongbri remarks that tribal institutions in themselves need not necessarily be democratic in its structure and functioning. Commenting on the Bhuria Committee Report that went into this issue Nongbri remarks that while the Committee’s concern for the traditional tribal institutions is appreciable, it fails to take stock of the complexity of the situation. For notwithstanding the strong egalitarian ethos that characterised tribal societies the element of stratification is not altogether absent. Tribal political institutions are not only marked by open intolerance to women but the process of social change has also introduced sharp distortions in the system, making it difficult to identify which is traditional and which is not. (Nongbri 2003: 220) This again brings you back to the changing nature of tradition that we discussed in chapter 1 and 2.

Democratisation and Inequality

It will be clear to you that democratisation is not easy in a society that has had a long history of inequality based on caste, community and gender. You have dealt with the different kinds of inequality in the earlier book. In chapter 4 you will get a fuller sense of rural Indian structure. Given this unequal and undemocratic social structure, it is not surprising that in many cases, certain members belonging to particular groups, communities, castes of the village are not included or informed about meetings and activities of the village. The Gram Sabha members are often controlled by a small coterie of rich landlords usually hailing from the upper castes or landed peasantry. They make decisions on development activities, allocate funds, leaving the silent majority as mere onlookers.

The reports in the boxes below show different kind of experiences at the grassroot level. One shows how traditional panchayats are being used. Another reports on how the new institution of Panchayati Raj, in some cases, are truly bringing in radical changes. Yet another on how democratic measures do not often work out in practice because interest groups resist change and money matters.

Bound by Honour

Caste panchayats are reasserting themselves as guardians of village morality….The first case that hit the headlines was in October 2004, when the Rathi khap panchayat in Asanda village of Jhajjar district ordered Sonia, who had already been married a year by then, to dissolve her marriage with Ram Pal, abort her unborn child and accept her husband as a brother if she wanted to stay in the village. The couple’s fault: sharing the same gotra even though the Hindu Marriage Act recognises such unions. Sonia and Ram Pal could live together again only after the high court directed the Haryana government to provide them security.

…One such jaati panchayat of Ansaris in Muzafarnagar decided in June last year that Imrana’s rape by her father-in-law had made her a mother to her husband. Another in a Meerut village ruled that Gudiya, pregnant with the child of her second husband, should return to her first who had reappeared after five years.

Source: Sunday Times (Times of India), New Delhi, October 29th 2006

Role of wealth and privilege? Role of villagers?

This time around, Soompa sarpanch seat fell within the quota reserved for women. Nevertheless panchayat residents considered this as a contest between the candidates’ husbands and a face-off among ‘equals’. On one hand was the incumbent sarpanch, Ram Rai Mewada who owns a liqour shop in Kekri and on the other Chand Singh Thakur, a rich landowner from the same village. Interestingly, Mewada had been exposed by the village residents for faking muster rolls in the drought relief works during 2002-03.

Although no action was taken against him, the villagers were determined to see him out of office this time and thus put up the thakur for a stiff competition. The residents of Sooma unanimousy decided that the thakur was best suited to oppose Mewada…

Role of social movements and organisations for greater participation and information

One such meeting took place on January 24 in Dhorela village (Kushalpura panchayat). The meeting was publicised by going from door-to-door and through announcements by gathering children, teaching them slogans where a worker from a very well reputed NGO led them around the village as they urged people to come to the chaupal for the meeting. …Tara’s (the local NGO supported candidate) ghoshana patra (manifestoe) was read out and she made a short speech. Her ghoshana patra, …included not just taking of bribes as sarpanch, not spending more than Rs. 2,000 on campaigning, etc. … Distribution of alcohol and gur, and the use of jeeps are frequently used means of buying votes and contribute to campaign expenditure. …The entire chain of corruption is explained to the gathered villagers: low cost elections not only allow the poor to participate, they also make corruption-free panchayats possiblity.

EXERCISE FOR BOXES 3.11, 3.12 AND 3.13

Read the boxes above carefully and discuss:

The role of wealth

The role of people

The role of women

3.3 Political parties, pressure groups and democratic politics

You will recall that this chapter began with the oft quoted definition of democracy as a form of government that is of the people, by the people and for the people. As the chapter unfolded you would have noticed how this definition captures the spirit of democracy but conceals the many divisions between one group of people and another. You have seen how interests and concerns are different. We have seen in section II on the Indian Constitution how different groups sought to represent their interests within the Constituent Assembly. We also saw in the story of Indian democracy the contending interests of different groups. A look at the newspaper every morning will show you many instances where different groups seek to make their voices heard. And draw the attention of the government to their grievances.

The question, however, arises whether all interest groups are comparable. Can an illiterate peasant or literate worker make her case to the government as coherently and convincingly as an industrialist? Neither the industrialist nor the peasant or worker, however, represents their case as individuals. Industrialists form associations such as Federation of Indian Chambers and Commerce (FICCI) and Association of Chambers of Commerce (ASSOCHAM). Workers form trade unions such as the Indian Trade Union Congress (INTUC) or the Centre for Indian Trade Unions (CITU). Farmers form agricultural unions such as Shetkari Sangathan. Agricultural labourers have their own unions. You will read about other kinds of organisations and social movements like tribal and environmental movements in the last chapter.

Activity 3.1

Follow any one newspaper or magazine for a week. Note down the many instances where there is a clash of interests.

Identify the issue over which the dispute occurs.

Identify the way the groups concerned take up their cause.

Is it a formal delegation of a political party to meet the Prime Minister or any other functionary?

Is it a protest on the streets?

Is it through writing or providing information in newspapers?

Is it through public meetings?

Identify the instances whether a political party, a professional association, a non governmental organisation or any other body takes up an issue.

Discuss the many actors in the story of Indian democracy.

In a democratic form of government political parties are key actors. A political party may be defined as an organisation oriented towards achieving legitimate control of government through an electoral process. Political Party is an organisation established with the aim of achieving governmental power and using that power to pursue a specific programme. Political parties are based on certain understanding of society and how it ought to be. In a democratic system the interests of different groups are also represented by political parties, who take up their case. Different interest groups will work towards influencing political parties. When certain groups feel that their interests are not being taken up, they may move to form an alternative party. Or they form pressure groups who lobby with the government. Interest Groups are organised to pursue specific interests in the political arena, operating primarily by lobbying the members of legislative bodies. In some situations, there may be political organisations which seek to achieve power but are denied the opportunity to do so through standard means. These organisations are best regarded as movements until they achieve recognition.

Every year at the tail end of February the Finance Minister of the Government of India presents the Budget to the Parliament. Prior to this there are reports every day in the newspaper of the meetings that the various confederation of Indian industrialists, of trade unions, farmers, and more recently womens’ groups had with the Ministry of Finance.

Exercise for Box 3.14

Can they be understood as pressure groups?

Whereas the genuine place of classes is within the economic order, the place of status groups is within the social order…But parties live in a house of power…

Party actions are always directed towards a goal which is striven for in a planned manner. The goal may be a ‘cause’ (the party may aim at realising a program for ideal or material purposes), or the goal may be ‘personal’ (sinecures, power, and from these, honour for the leader and followers of the party).

(Weber 1948: 194)

Exercise for Box 3.16

Read the box on the next page carefully. You can also draw from other similar events in other towns and cities.

Identify the interests of the poor, the serving class, the middle class and the rich.

How do the different groups see the role of the street?

Discuss what you think is the role of the government?

What is the role of consultancy firms like McKinsey? Whose interests do they represent?

What is the role of political parties?

Do you think the poor can influence political parties more than they can influence consultancy firms? Is it because political parties are accountable to the people that is i.e., they can be voted out?

BOX 3.16

Recent years have seen a great focus on making Indian cities global cities. For urban planners and dreamers, Mumbai urgently needs north-south and east-west connectivity. Towards this, they argue for the need to construct an ‘express ring freeway’ to circle the city ‘such that a freeway can be accessed from any point in the city in less than 10 minutes’. ‘Quick entry and exit’, and ‘efficient traffic dispersal’ are seen as critical to the smooth functioning of the city….

For the less privileged the streets have a different role to play. They are more than freeways of connectivity. Streets, for good or bad, all too often become effectively bazaars, and melas combining the different purposes of pilgrimage, recreation (transportation) and economic exchange. As people blur the boundaries between public and private space by living on the street, buying and selling, eating, drinking tea, playing cricket or even just standing, urban planners point to how these activities impeded traffic and cause congestion.

In order to decongest, poor people are shifted to the outskirts. In the Vision Mumbai document prepared by the private consultancy from McKinsey…mass housing for the poor is being planned in the salt pan lands outside the city. What happens to their livelihood? The long quote below captures the voice of the poor.

“We are in fact human earthmovers and tractors. We levelled the land first. We have contributed to the city. We carry your shit out of the city. I don’t see citizens’ groups dredging sewers and digging roads. The city is not for the rich only. We need each other. I don’t beg. I wash your clothes. Women can go to work because we are there to look after their children. The staff in Mantralay, the collectorate, the BMC, even the police live in slums. Because we are there, women can walk safely at night….Groups such as Bombay First talk about Mumbai a world class city. How can it be a world-class city without a place for its poor? (Anand 2006: 3422)

Questions

1. Interest groups are part and parcel of a functioning democracy. Discuss.

2. Read the snippets from the debates held in the Constituent Assembly. Identify the interest groups. Discuss what kind of interest groups exist in contemporary India. How do they function?

3. Create a’ phad’ or a scroll with your own mandate when standing for school election. (this could be done in small groups of 5, like a panchayat)

3. Have you heard of Bal Panchayats and Mazdoor Kissan Sanghathan? If not, find out and write a note about them in about 200 words.

4. The 73rd amendment has been monumental in bringing a voice to the people in the villages. Discuss.

5. Write an essay on the ways that the Indian Constitution touches peoples’ everyday life, drawing upon different examples.

REFERENCES

Anand, Nikhil. 2006. ‘Disconnecting Experience: Making World Class Roads in Mumbai’. Economic and Political Weekly (August 5th). pp. 3422-3429. Ambedkar, Babasaheb. 1992. ‘The Buddha and His Dharma’ in V. Moon (Ed.) Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches. Vol. 11. Bombay Educational Department. Government of Maharashtra. Sen, Amartya. 2004. The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture and Identity. Allen Lane. Penguin Group. London. Weber, Max. 1948. Essays in Sociology Ed. with an introduction by H.H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. Routledge and Kegan Paul. London.