Table of Contents

5

Change and Development in Industrial Society

Which was the last film you saw? We are sure you can tell us the name of the hero and heroine but can you remember the name of the sound and light technicians, the make up artists or the dance choreographers? Some people like the carpenters who make the sets are not even mentioned in the credits. Yet, without all these people, the film could not be made. Bollywood may be a place of dreams for you and me, but for many, it is their place of work. Like any industry, the workers there are part of unions. For instance, the dancers, stunt artists and the extras are all part of a junior artists association, whose demands include 8 hours shifts, proper wages and safe working conditions. The products of this industry are advertised and marketed through film distributors and cinema hall owners or through shops in the form of music cassettes and videos. And the people who work in this industry, as in any other, live in the same city, but depending on who they are and how much they earn, they do very different things in that city. Film stars and textile mill owners live in places like Juhu, while extras and textile workers may live in places like Girangaon. Some go to five star hotels and eat Japanese sushi and some eat vada pav from the local handcart. The residents of Mumbai are divided by where they live, what they eat and how much their clothes cost. But they are also united by certain common things that a city provides – they watch the same films and cricket matches, they suffer from the same air pollution and they all have aspirations for their children to do well.

How and where people work and what kind of jobs they have is an important part of who they are. In this chapter, we will see how changes in technology or the kind of work that is available has changed social relations in India. On the other hand, social institutions like caste, kinship networks, gender and region also influence the way that work is organised or the way in which products are marketed. This is a major area of research for sociologists.

For instance, why do we find more women in certain jobs like nursing or teaching than in other sectors like engineering? Is this just a coincidence or is it because society thinks that women are suited for caring and nurturing work as against jobs which are seen as ‘tough’ and masculine? Yet nursing is physically much harder work than designing a bridge. If more women move into engineering, how will that affect the profession? Ask yourself why some coffee advertisements in India display two cups on the package whereas in America they show one cup? The answer is that for many Indians drinking coffee is not an individual wake up activity, but an occasion to socialise with others. Sociologists are interested in the questions of who produces what, who works where, who sells to whom and how. These are not individual choices, but outcomes of social patterns. In turn, the choices that people make influences how society works.

5.1 Images of Industrial Society

Many of the great works of sociology were written at a time when industrialisation was new and machinery was assuming great importance. Thinkers like Karl Marx, Max Weber and Emile Durkheim associated a number of social features with industry, such as urbanisation, the loss of face-to-face relationships that were found in rural areas where people worked on their own farms or for a landlord they knew, and their substitution by anonymous professional relationships in modern factories and workplaces. Industrialisation involves a detailed division of labour. People often do not see the end result of their work because they are producing only one small part of a product. The work is often repetitive and exhausting. Yet, even this is better than having no work at all, i.e., being unemployed. Marx called this situation alienation, when people do not enjoy work, and see it as something they have to do only in order to survive, and even that survival depends on whether the technology has room for any human labour.

Industrialisation leads to greater equality, at least in some spheres. For example, caste distinctions do not matter any more on trains, buses or in cyber cafes. On the other hand, older forms of discrimination may persist even in new factory or workplace settings. And even as social inequalities are reducing, economic or income inequality is growing in the world. Often social inequality and income inequality overlap, for example, in the domination of upper caste men in well-paying professions like medicine, law or journalism. Women often get paid less than men for similar work.

Activity 5.1

According to the convergence thesis put forward by modernisation theorist Clark Kerr, an industrialised India of the 21st century shares more features with China or the United States in the 21st century than it shares with 19thcentury India. Do you think this is true? Do culture, language and tradition disappear with new technology or does culture influence the way people adapt to new products? Write a page of your own reflections on these issues, giving examples.

While the early sociologists saw industrialisation as both positive and negative, by the mid 20th century, under the influence of modernisation theory, industrialisation came to be seen as inevitable and positive. Modernisation theory argues that societies are at different stages on the road to modernisation, but they are all heading in the same direction. Modern society, for these theorists, is represented by the West.

5.2 Industrialisation in India

The Specificity of Indian Industrialisation

The experience of industrialisation in India is in many ways similar to the western model and in many ways different. Comparative analysis of different countries suggests that there is no standard model of industrial capitalism. Let us start with one point of difference, relating to what kind of work people are doing. In developed countries, the majority of people are in the services sector, followed by industry and less than 10% are in agriculture (ILO figures). In India, in 1999-2000, nearly 60% were employed in the primary sector (agriculture and mining), 17% in the secondary sector (manufacturing, construction and utilities), and 23% in the tertiary sector (trade, transport, financial services etc.) However, if we look at the contribution of these sectors to economic growth, the share of agriculture has declined sharply, and services contribute approximately more than half. This is a very serious situation because it means that the sector where the maximum people are employed is not able to generate much income for them. (Government of India, Economic Survey 2001-2002). In India, in 2006-07 the share of employment in agriculture was 15.19%, in mining and quarriying 0.61%, in production 13.33%, in manufacturing it was 6.10%, in trade, hotel and restaurant it was 13.18%, in transport, storage, communication it was 5.06%, in community, social and personal services it was 8.97%, in financial insurance, real state, business services it was 2.22% and electricity and water it was 0.33% (Source- Planning Commission 11th Five Year Plan, 2007-12, Vol. I, Page 66).

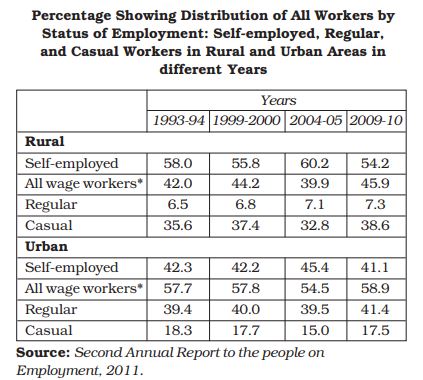

Another major difference between developing and developed countries is the number of people in regular salaried employment. In developed countries, the majority are formally employed. In India, over 50% of the population is self-employed, only about 14% are in regular salaried employment, while approx-imately 30% are in casual labour (Anant 2005: 239). The adjacent chart shows the changes between 1977-78 and 1999-2000.

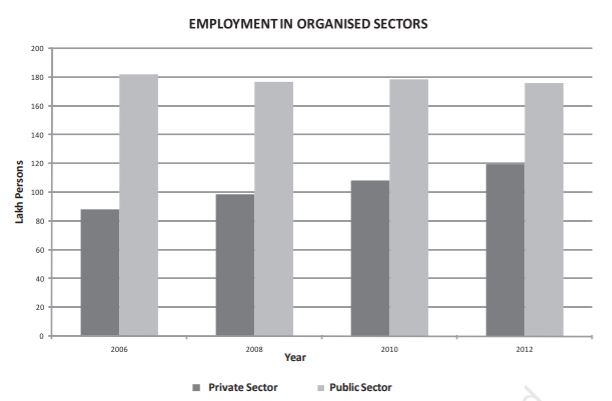

Economists and others often make a distinction between the organised or formal and unorganised or informal sector. There is a debate over how to define these sectors. According to one definition, the organised sector consists of all units employing ten or more people throughout the year. These have to be registered with the government to ensure that their employees get proper salaries or wages, pension and other benefits. In India, over 90% of the work, whether it is in agriculture, industry or services is in the unorganised or informal sector. What are the social implications of this small size of the organised sector?

First, it means that very few people have the experience of employment in large firms where they get to meet people from other regions and backgrounds. Urban settings do provide some corrective to this – your neighbours in a city may be from a different place – but by and large, work for most Indians is still in smallscale workplaces. Here personal relationships determine many aspects of work. If the employer likes you, you may get a salary raise, and if you have a fight with him or her, you may lose your job. This is different from a large organisation with well-defined rules, where recruitment is more transparent and there are mechanisms for complaints and redressal if you disagree with your immediate superior. Second, very few Indians have access to secure jobs with benefits. Of those who do, two-thirds work for the government. This is why government jobs are so popular. The rest are forced to depend on their children in their old age. Government employment in India has played a major role in overcoming boundaries of caste, religion and region. One sociologist has argued that the reason why there have never been communal riots in a place like Bhilai is because the public sector Bhilai Steel Plant employs people from all over India who work together. Others may question this. Third, since very few people are members of unions, a feature of the organised sector, they do not have the experience of collectively fighting for proper wages and safe working conditions. The government has laws to monitor conditions in the unorganised sector, but in practice they are left to the whims and fancies of the employer or contractor.

Industrialisation in the Early Years of Indian Independence

The first modern industries in India were cotton, jute, coal mines and railways. After independence, the government took over the ‘commanding heights of the economy.’ This involved defence, transport and communication, power, mining and other projects which only government had the power to do, and which was also necessary for private industry to flourish. In India’s mixed economy policy, some sectors were reserved for government, while others were open to the private sector. But within that, the government tried to ensure, through its licensing policy, that industries were spread over different regions. Before independence, industries were located mainly in the port cities like Madras, Bombay, Calcutta (now, Chennai, Mumbai and Kolkata, respectively). But since then, we see that places like Baroda, Coimbatore, Bengaluru, Pune, Faridabad and Rajkot have become important industrial centres. The government also tried to encourage the small-scale sector through special incentives and assistance. Many items like paper and wood products, stationery, glass and ceramics were reserved for the small-scale sector. In 1991, large-scale industry employed only 28 per cent of the total workforce engaged in manufacture, while the small-scale and traditional industry employed 72 per cent (Roy 2001:11).

Globalisation, Liberalisation and changes in Indian industry

Since the 1990s, however, the government has followed a policy of liberalisation. Private companies, especially foreign firms, are encouraged to invest in sectors earlier reserved for the government, including telecom, civil aviation, power etc. Licenses are no longer required to open industries. Foreign products are now easily available in Indian shops. As a result of liberalisation, many Indian companies have been bought over by multinationals. At the same time some Indian companies are becoming multinational companies. An instance of the first is when, Parle drinks was bought by Coca Cola. Parle’s annual turnover was Rs. 250 crores, while Coca Cola’s advertising budget alone was Rs. 400 crores. This level of advertising has naturally increased the consumption of coke across India replacing many traditional drinks. The next major area of liberalisation may be in retail. Do you think that Indians will prefer to shop in departmental stores, or will they go out of business?

The government is trying to sell its share in several public sector companies, a process which is known as disinvestment. Many government workers are scared that after disinvestment, they will lose their jobs. In Modern Foods, which was set up by the government to make healthy bread available at cheap prices, and which was the first company to be privatised, 60% of the workers were forced to retire in the first five years.

Let us see how this fits in with worldwide trends. More and more companies are reducing the number of permanent employees and outsourcing their work to smaller companies or even to homes. For multinational companies, this outsourcing is done across the globe, with developing countries like India providing cheap labour. Because small companies have to compete for orders from the big companies, they keep wages low, and working conditions are often poor. It is more difficult for trade unions to organise in smaller firms. Almost all companies, even government ones, now practice some form of outsourcing and contracting. But the trend is especially visible in the private sector.

To summarise, India is still largely an agricultural country. The service sector – shops, banks, the IT industry, hotels and other services are employing more people and the urban middle class is growing, along with urban middle class values like those we see in television serials and films. But we also see that very few people in India have access to secure jobs, with even the small number in regular salaried employment becoming more insecure due to the rise in contract labour. So far, employment by the government was a major avenue for increasing the well-being of the population, but now even that is coming down. Some economists debate this, but liberalisation and privatisation worldwide appear to be associated with rising income inequality. You will be reading more about this in the next chapter on globalisation.

Retail chains scramble to enter Indian market

Clamoring to enter India’s red-hot retail sector, the world’s largest chains, including Wal-Mart Stores, Carrefour and Tesco, are seeking the best way to enter the country, despite a government ban on foreign direct investment in the market. Recent large investments by major Indian businesses, like Reliance Industries and Bharti Airtel, have increased the sense of urgency for foreign retailers…..Last week, Bharti Airtel indicated that it was in talks with Wal-Mart, Carrefour and Tesco to set up a retailing joint venture….India’s retail sector is attractive not only because of its fast growth, but because family-run street corner stores have 97% of the nation’s business. But this industry trait is precisely why the government makes it hard for foreigners to enter the market. Politicians frequently argue that global retailers would destroy thousands of small local players and fledgling domestic chains.

Source: International Herald Tribune, 3 August 2006

At the same time as secure employment in large industry is declining, the government is embarking on a policy of land acquisition for industry. These industries do not necessarily provide employment to the people of the surrounding areas, but they cause major pollution. Many farmers, especially adivasis, who constitute approximately 40% of those displaced, are protesting at the low rates of compensation and the fact that they will be forced to become casual labour living and working on the footpaths of India’s big cities. You will recall the discussion on competing interests in chapter 3.

In the following sections, we will look at how people find work, what they actually do in their workplaces and what kind of working conditions they face.

5.3 How people find jobs

If you open the Times of India on a Wednesday morning, you will find a section called Times Ascent. Here, jobs are advertised, and tips are given about how to motivate yourself or your workers to perform better.

Box 5.2 on the next page shows an example of a public sector job. The person will get benefits like house rent allowance (HRA). The qualifications required for the job are specified in great detail. In such jobs there are clear avenues for promotions, and you can expect that seniority will matter.

Let us look at a private sector job in Box 5.3 on the next page. This is also regular salaried employment and the employer is a well-known hotel. But here the salary and qualifications required are flexible, and the job is likely to be on contract. Look at the language used in this advertisement, such as loyalty programme. Each organisation tries to create its own work culture.

But only a small percentage of people get jobs through advertisements or through the employment exchange. People who are self-employed, like plumbers, electricians and carpenters at one end and teachers who give private tuitions, architects and freelance photographers at the other end, all rely on personal contacts. They hope that their work will be an advertisement for them. Mobile phones have made life much easier for plumbers and others who can now cater to a wider circle of people.

Job recruitment as a factory worker takes a different pattern. In the past, many workers got their jobs through contractors or jobbers. In the Kanpur textile mills, these jobbers were known as mistris, and were themselves workers. They came from the same regions and communities as the workers, but because they had the owner’s backing they bossed over the workers. On the other hand, the mistri also put community-related pressures on the worker. Nowadays, the importance of the jobber has come down, and both management and unions play a role in recruiting their own people. Many workers also expect that they can pass on their jobs to their children. Many factories employ badli workers who substitute for regular permanent workers who are on leave. Many of these badli workers have actually worked for many years for the same company but are not given the same status and security. This is what is called contract work in the organised sector. Employment opportunities have two important components:

(i) job in an organisation

(ii) Self-employment

The schemes of the Government of India, like ‘Stand Up India Scheme’ and ‘Make in India’ are programmes by which employment and self-employment will become possible. These schemes are helpful to people of the marginalised sections of the society, like SC, ST and other backward classes. These are positive signs for creating economic potential amongst the demographic dividend of India.

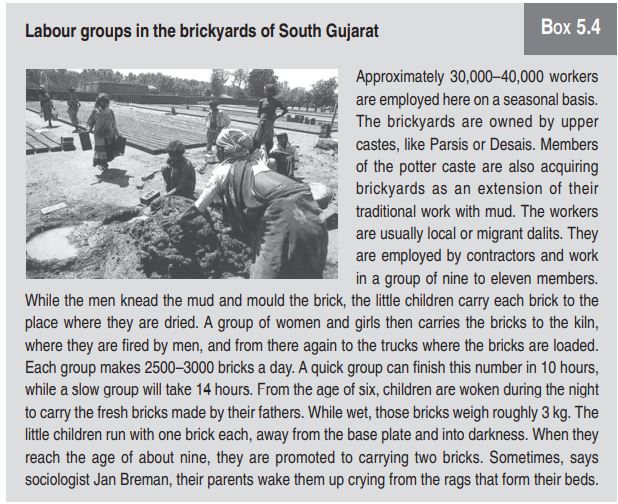

However, the contractor system is most visible in the hiring of casual labour for work at construction sites, brickyards, and so on. The contractor goes to villages and asks if people want work. He will loan them some money. This loan includes the cost of transport to the work site. The loaned money is treated as an advance wage and the worker works without wages until the loan is repaid. In the past, agricultural labourers were tied to their landlord by debt. Now, however, by moving to casual industrial work, while they are still in debt, they are not bound by other social obligations to the contractor. In that sense, they are more free in an industrial society. They can break the contract and find another employer. Sometimes, whole families migrate and the children help their parents.

Dyal Singh College

(Delhi University Maintained College)

Lodi Road, New Delhi 110003

Applications are invited for the post of PRINCIPAL in the scale of pay Rs. 16,400-22400 (with a minimum of Rs. 17,300 p.m.) plus D.A., CCA, H.R.A., T.A. and other benefits as permissible under the rules of the University of Delhi.

QUALIFICATIONS

(i) A Master’s Degree in a relevant subject with at least 55% marks or an quivalent grade of ‘B’ in the seven point scale with letter grade O, A, B, C, D, E & F.

(ii) Ph.D. or equivalent degree

(iii) Total experience of fifteen years of teaching and/or post-doctoral research in Universities/Colleges and other institution of higher education.

Applications stating full details of qualifications, experience, age, etc. with all the supporting documents should reach “The Chairman, Governing Body, Dyal Singh College, Lodi Road, New Delhi – 110 003” in a sealed cover within 15 days from the date of publication of this advertisement.

Chairman

Governing Body

Radisson Hotel Delhi has

immediate openings

for their loyalty program.

Customer Service Executives

Senior Tele-sales Executives

Candidates with a good command over English and a flair for sales may apply.

Prior experience preferred.

We offer a 5 star work environment, ongoing development and training, motivating atmosphere, day time jobs and good salary/incentives.

Part time & full time options available.

Please call between 9.30 am to 6.30 pm

30th- 31st August & 1st September, 2006

Ph: 66407361/66407351/66407353

Or Fax your CV to 26779062

Or Email: [email protected]

Radisson

5.4 How is work carried out?

In this section, we will explore how work actually takes place. How are all the products we see around us manufactured? What is the relationship between managers and workers in a factory or in an office? In India, there is a whole range of work settings from large companies where work is automated to small home-based production.

The basic task of a manager is to control workers and get more work out of them. There are two main ways of making workers produce more. One is to extend the working hours. The other is to increase the amount that is produced within a given time period. Machinery helps to increase production, but it also creates the danger that eventually machines will replace workers. Both Marx and Mahatma Gandhi saw mechanisation as a danger to employment.

Another way of increasing output is by organising work. An American called Frederick Winslow Taylor invented a new system in the 1890s, which he called ‘Scientific Management’. It is also known as Taylorism or industrial engineering. Under his system, all work was broken down into its smallest repetitive elements, and divided between workers. Workers were timed with the help of stopwatches and had to fulfil a certain target every day. Production was further speeded up by the introduction of the assembly line. Each worker sat along a conveyor belt and assembled only one part of the final product. The speed of work could be set by adjusting the speed of the conveyor belt. In the 1980s, there was an attempt to shift from this system of direct control to indirect control, where workers are supposed to motivate and monitor themselves. But often we find that the old Taylorist processes survive.

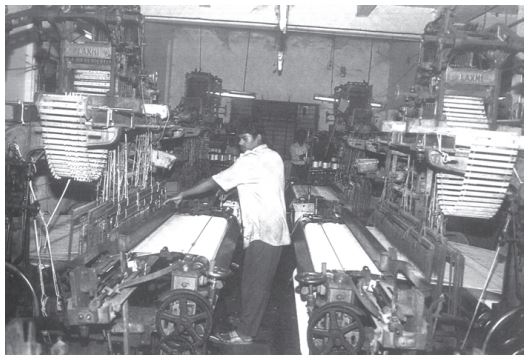

Workers in textile mills, which is one of the oldest industries in India, often described themselves as extensions of the machine. Ramcharan, a weaver who had worked in the Kanpur cotton mills since the 1940s, said:

You need energy. The eyes move, the neck, the legs and the hands, each part moves. Weaving is done under a continuous gaze - one cannot go anywhere, the focus must be on the machine. When four machines run all four must move together, they must not stop. (Joshi 2003)

The more mechanised an industry gets, the fewer people are employed, but they too have to work at the pace of the machine. In Maruti Udyog Ltd. two cars roll off the assembly line every minute. Workers get only 45 minutes rest in the entire day - two tea breaks of 7.5 minutes each and one lunch break of half an hour. Most of them are exhausted by the age of 40 and take voluntary retirement. While production has gone up, the number of permanent jobs in the factory has gone down. The firm has outsourced all services like cleaning, and security, as well as the manufacture of parts. The parts suppliers are located around the factory and send the parts every two hours or just-in-time. Outsourcing and just-in-time keeps costs low for the company, but the workers are very tense, because if the supplies fail to arrive, their production targets get delayed, and when they do arrive they have to run to keep up. No wonder they get exhausted.

Now let us look at the services sector. Software professionals are middle class and well educated. Their work is supposed to be self-motivated and creative. But, as we see from the box, their work is also subject to Taylorist labour processes.

‘Time Slavery’ in the IT Sector

An average work day has 10-12 hours and it is not uncommon for employees to stay overnight in the office (known as a ‘night out’), when faced with a project deadline. Long working hours are central to the industry’s ‘work culture’. In part, this is due to the time difference between India and the client site, such that conference calls tend to take place in the evening when the working day in the U.S. begins. Another reason is that overwork is built into the structure of outsourced projects: project costs and timelines are usually underestimated in terms of mandays, and because mandays are based on an eight-hour day, engineers have to put in extra hours and days in order to meet the deadlines. Extended working hours are legitimised by the common management practice of ‘flexi-time’, which in theory gives an employee freedom to choose his or her working hours (within limits) but, which in practice, means that they have to work as long as necessary to finish the task at hand. But even when there is no real work pressure, they tend to stay late in office either due to peer pressure or because they want to show the boss that they are working hard.

(Carol Upadhya, Forthcoming)

As a result of these working hours, in places like Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Gurugram, where many IT firms or call centres are located, shops and restaurants have also changed their opening hours, and are open late. If both husband and wife work, then children have to be put in crèches. The joint family, which was supposed to have disappeared with industrialisation, seems to have re-emerged, as grandparents are roped in to help with children.

One important debate in sociology is whether industrialisation and the shift to services and knowledge-based work, like IT, leads to greater skills in society. We often hear the phrase ‘knowledge economy’ to describe the growth of IT sector in India. But how do you compare the skills of a farmer who knows how to grow many hundreds of crops relying on his or her understanding of the weather, the soil and the seeds, with the knowledge of a software professional? Both are skilled but in different ways. The famous sociologist, Harry Braverman, argues that the use of machinery actually deskills workers. For example, whereas earlier architects and engineers had to be skilled draughtsmen, now the computer does a lot of the work for them.

5.5 Working conditions

We all want power, a solid house, clothes and other goods, but we should remember that these come to us because someone is working to produce them, often in very bad conditions. The government has passed a number of laws to regulate working conditions. Let us look at mining, where a number of people are employed. Coal mines alone employ 5.5 lakh workers. The Mines Act 1952 specifies the maximum number of hours a person can be made to work in a week, the need to pay overtime for any extra hours worked and safety rules. These rules may be followed in big companies, but not in smaller mines and quarries. Moreover, sub-contracting is widespread. Many contractors do not maintain proper registers of workers, thus avoiding any responsibility for accidents and benefits. After mining has finished in an area, the company is supposed to cover up the open holes and restore the area to its earlier condition. But they don’t do this.

Workers in underground mines face very dangerous conditions, due to flooding, fire, the collapse of roofs and sides, the emission of gases and ventilation failures. Many workers develop breathing problems and diseases like tuberculosis and silicosis. Those working in overground mines have to work in both hot sun and rain, and face injuries due to mine blasting, falling objects etc. The rate of mining accidents in India is very high compared to other countries.

Time running out for 54 trapped miners in Jharkhand

IANS, September 7, 2006

54 miners at the Bhatdih colliery of Nagada were trapped Wednesday night following a blast due to the accumulation of gases. It was about 8 p.m. when the explosion, caused by the pressure due to the accumulation of methane and carbon monoxide, shook the colliery belonging to the Bharat Coking Coal Limited (BCCL). The intensity was so high that a one-tonne trolley in inclination number 17 was thrown out.

Four rescue teams have been constituted. But they don’t have adequate number of oxygen masks to enter the deep mine where the incident occurred.

Most of the trapped miners are between the ages of 20 and 30.

Family members and union leaders have blamed the BCCL management for the incident. ‘This is one of the BCCL’s poisonous mines. No safety measures have been adopted by the management. Water sprinkling facilities and gas testing machines should be available in the colliery. But no such arrangements have been made here,’ said a union member.

In many industries, the workers are migrants. The fish processing plants along the coastline employ mostly single young women from Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala. Ten-twelve of them are housed in small rooms, and sometimes one shift has to make way for another. Young women are seen as submissive workers. Many men also migrate singly, either unmarried or leaving their families in the village. In 1992, 85% of the 2 lakh Oriya migrants in Surat were single. These migrants have little time to socialise and whatever little time and money they can spend is with other migrant workers. From a nation of interfering joint families, the nature of work in a globalised economy is taking people in the direction of loneliness and vulnerability. Yet for many young women, it also represents some independence and economic autonomy.

5.6 Home-based work

Home-based work is an important part of the economy. This includes the manufacture of lace, zari or brocade, carpets, bidis, agarbattis and many such products. This work is mainly done by women and children. An agent provides raw materials and also picks up the finished product. Home workers are paid on a piece-rate basis, depending on the number of pieces they make.

Let us look at the bidi industry. The process of making bidis starts in forested villages where villagers pluck tendu leaves and sell it to the forest department or a private contractor who in turn sells it to the forest department. On average a person can collect 100 bundles (of 50 leaves each) a day. The government then auctions the leaves to bidi factory owners who give it to the contractors. The contractor in turn supplies tobacco and leaves to home-based workers. These workers, mostly women, roll the bidis – first dampening the leaves, then cutting them, filling in tobacco evenly and then tying them with thread. The contractor picks up these bidis and sells them to the manufacturer who roasts them, and puts on his own brand label. The manufacturer then sells them to a distributor who distributes the packed bidis to wholesalers who in turn sell to your neighbourhood pan shops.

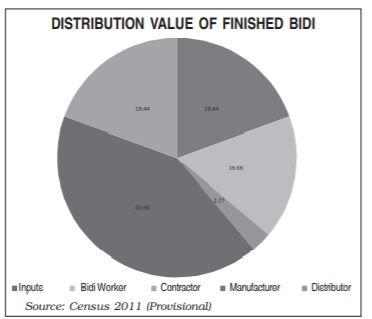

Let us see from the following pie diagram how the value of the finished bidi is distributed. The manufacturer gets the maximum amount because of the image of the brand, showing the power of images.

Life history of a bidi worker

Madhu is a 15-year old school dropout. She stopped going to school after failing in Class VIII. Her father, a tailor, expired last year. He was suffering from tuberculosis. This made it necessary for the children and their mother to work. Her elder brother aged 17 years works in a grocery shop and the younger one aged 14 years is engaged in chocolate packaging. Madhu and her mother roll bidis. Madhu started rolling bidis at an early age and she enjoys it as it provides her the opportunity to sit close to her mother and other women and listen to them chat. She fills tobacco into the rolled tendu leaves. She spends most of her time in this activity apart from the time spent doing household chores. Due to long hours of sitting in the same posture daily, she suffers from backache. Madhu wants to restart her schooling. (Bhandari 2005: 406)

5.7 Strikes and unions

Many workers are part of trade unions. Trade unions in India have to overcome a number of problems, such as regionalism and casteism. Datta Iswalkar, a mill worker, described how caste had been overcome but not entirely in the Mumbai mills:

They would sit and chew paan with him (Vishnu, a Mahar worker in Modern Mills) but they would not drink water from his hands! They never treated him badly, they were friends with him, but they would never go to his house. Or eat out of a lunchbox bought by any of the Mahars. The funny thing is the Marathi workers were unable to judge the caste of the North Indian workers. So they could not practice untouchability with them!

(Menon and Aadarkar, 2004: 113)

In response to harsh working conditions, sometimes workers went on strike. In a strike, workers do not go to work. In a lockout the management shuts the gate and prevents workers from coming. To call a strike is a difficult decision as managers may try to use substitute labour. Workers also find it hard to sustain themselves without wages.

Let us look at one famous strike, the Bombay Textile strike of 1982, which was led by the trade union leader, Dr. Datta Samant, and affected nearly a quarter of a million workers and their families. The strike lasted nearly two years. The workers wanted better wages and also wanted the right to form their own union. According to the Bombay Industrial Relations Act (BIRA), a union had to be ‘approved’ and the only way it could be ‘approved’ was if it gave up the idea of strikes. The Congress-led Rashtriya Mill Mazdoor Sangh (RMMS) was the only approved union and it helped to break the strike by bringing in other workers. The government also refused to listen to the workers’ demands. Slowly after two years, people started going back to work because they were desperate. Nearly one lakh workers lost their jobs and went back to their villages, or took up casual labour, others moved to smaller towns, like Bhiwandi, Malegaon and Icchalkaranji, to work in the powerloom sector. Mill owners did not invest in machinery and modernisation. Today, they are trying to sell off the mill land to real estate dealers to build luxury apartments, leading to a battle over who will define the future of Mumbai – the workers who built it or the mill owners and real estate agents.

Jayprakash Bhilare, ex-millworker, General Secretary of the Maharashtra Girni Kamgar Union: Textile workers were getting only their basic wage and DA, and no other allowance. We were getting only five days Casual Leave. Other workers in other industries had started getting allowances for travelling, health benefits, etc., and 10-12 days’ Casual Leave. This agitated the textile workers…On 22 October 1981, the workers of Standard Mills marched to the house of Dr. Datta Samant to ask him to lead them. At first Samant declined, saying the industry was covered by the BIRA and he did not know enough of the textile industry. These workers were in no mood to take no for an answer. They kept a night-long vigil outside his home and in the morning Samant finally relented.

Lakshmi Bhatkar, participant in the strike: I supported the strike. We would sit outside the gate every day and discuss what was to be done. We would go for the morcha that was organised from time to time…the morchaalways used to be huge – we never looted or hurt anybody. I was asked to speak sometimes but I was not able to make speeches. My legs would shake too much! Besides I was afraid of my children – what would they say? They would think here we are starving at home and she has her face printed in the newspapers…There was a morchato Century Mills showroom once. We were arrested and taken to Borivali. I was thinking about my children. I could not eat. I thought to myself that we are not criminals, we were mill workers, fighting for the wages of our blood.

Kisan Salunke, ex-millworker, Spring Mills: Century Mills was opened by the RMMS barely a month-and-half after the strike began. They could do this because they had the full backing of the state and the government. They brought outsiders into the mill and they kept them inside without letting them out at all… Anantrao Bhonsle (Chief Minister of Maharashtra then) offered a 30–rupee raise. Datta Samant called a meeting to discuss this. All the leading activists were there. We said, ‘No, we don’t want this. If there is no dignity, if there is no discussion with the strike leaders, we will not be able to go back to work without any harassment.”

Datta Iswalkar, President of the Mill Chawls Tenant Association: The Congress brought all the goondas out of jail to break the strike like Babu Reshim, Rama Naik and Arun Gawli. They started to threaten the workers.

Bhai Bhonsle, General Secretary of the RMMS during 1982 strike: We started getting people to work in the mills after three months of the strike…Our point was, if people want to go to work let them, in fact they should be helped. …About the mafia gangs being involved, I was responsible for that…These Datta Samant people would wait at convenient locations and lie in wait for those going to work. We set up counter groups in Parel and other places. Naturally there were some clashes, some bloodshed…When Rama Naik died, Bhujbal who was Mayor then, had come in his official car to pay his respects. These forces were used at one time or other by many people in politics.

Kisan Salunke, ex-millworker: Those were very difficult times. We had to sell all our vessels. We were ashamed to go to the market with our vessels so we would wrap them in gunny bags and take them to the shop to sell ..There were days when I had nothing to eat, only water. We bought sawdust and burnt it for fuel. I have three sons. Sometimes when the children had no milk to drink, I could not bear to see them hungry. I would take my umbrella and go out of the house.

Sindu Marhane, ex-millworker: The RMMS and goondas came for me too, to force me back to work. But I refused to go….There were rumours going round as to what happened to women who went to stay and work in the mills. There were incidents of rape.

EXERCISE FOR BOX 5.8

After reading these accounts of the 1982 strike answer the questions given below.

1. Describe the 1982 textile strike from the different perspectives of those involved.

2. Why did the workers go on strike?

3. How did Datta Samant take up the leadership of the strike?

4. What was the role played by strike-breakers?

5. How did the mafia get a foothold in these areas?

6. How were women affected and what were their concerns during the strike?

7. How did workers and their families survive the period of strike?

1. Choose any occupation you see around you – and describe it along the following lines: a) social composition of the work force – caste, gender, age, region; b) labour process – how the work takes place, c) wages and other benefits, d) working conditions – safety, rest times, working hours etc.

or

2. In the account of brickmaking, bidi rolling, software engineers or mines that are described in the boxes, describe the social composition of the workers. What are the working conditions and facilities available? How do girls like Madhu feel about their work?

3. How has liberalisation affected employment patterns in India?

References

Anant, T.C.A. 2005. ‘Labour Market Reforms in India: A Review’. In Bibek Debroy and P.D. Kaushik Eds. Reforming the Labour Market. pp. 235-252. Academic Foundation. New Delhi.

Bhandari, Laveesh. ‘Economic Efficiency of Sub-contracted Home-based Work’. In Bibek Debroy and P.D. Kaushik Eds. Reforming the Labour Market. pp. 397-417. Academic Foundation. New Delhi.

Breman, Jan. 2004. The Making and Unmaking of an Industrial Working Class. Oxford University Press. New Delhi.

Breman, Jan. 1999. ‘The Study of Industrial Labour in post-colonial India – The Formal Sector: An Introductory review’. Contributions to Indian Sociology.

Vol 33 (1&2), January-August 1999. pp. 1-42.

Breman, Jan. 1999. ‘The Study of Industrial Labour in post-colonial India – The Informal Sector: A concluding review’. Contributions to Indian Sociology.

Vol 33 (1&2), January-August 1999. pp. 407-431.

Breman, Jan and Arvind, N. Das. 2000. Down and Out: Labouring Under Global Capitalism. Oxford University Press. Delhi.

Datar, Chhaya. 1990. ‘Bidi Workers in Nipani’. In Illina Sen, A Space within the Struggle. pp. 1601-81. Kali for Women. New Delhi.

Gandhi, M.K. 1909. Hind Swaraj and other writings. Edited by Anthony J. Parel. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

George, Ajitha Susan. 2003. Laws Related to Mining in Jharkhand. Report for UNDP.

Holmstrom, Mark. 1984. Industry and Inequality: The Social Anthropology of Indian Labour. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Joshi, Chitra. 2003. Lost Worlds: Indian Labour and its Forgotten Histories Delhi. Permanent Black. New Delhi.

Kerr, Clark et al. 1973. Industrialism and Industrial Man. Penguin. Harmondsworth.

Kumar, K. 1973. Prophecy and Progress. Allen Lane. London.

Menon, Meena and Neera, Adarkar. 2004. One Hundred Years, One Hundred Voices: the Millworkers of Girangaon: An Oral History. Seagull Press. Kolkata.

PUDR. 2001. Hard Drive: Working Conditions and Workers Struggles at Maruti. PUDR. Delhi.

Roy, Tirthankar. 2001. ‘Outline of a History of Labour in Traditional Small-scale Iindustry in India’. NLI Research Studies Series. No 015/2001. V.V. Giri National Labour Institute. Noida.

Upadhya, Carol. forthcoming. Culture Incorporated: Control over Work and Workers in the Indian Software Outsourcing Industry.