Table of Contents

5

Before you read

Can a shoemaker be called an artist? Yes, if he has the same skill and pride in his trade as any other artist, and the same respect for it too. Mr Gessler, a German shoemaker settled in London, is a perfect artist. Read this story to see how he devotes his life to his art.

Quality

I knew him from the days of my extreme youth, because he made my father’s boots. He lived with his elder brother in his shop, which was in a small by-street in a fashionable part of London.

The shop had a certain quiet distinction. There was no sign upon it other than the name of Gessler Brothers; and in the window a few pairs of boots. He made only what was ordered, and what he made never failed to fit. To make boots—such boots as he made—seemed to me then, and still seems to me, mysterious and wonderful.

I remember well my shy remarks, one day, while stretching out to him my youthful foot. “Isn’t it awfully hard to do, Mr Gessler?” And his answer, given with a sudden smile from out of the redness of his beard: “Id is an ardt!’’

“It is an art.” (said with a German accent)

lasted terribly: lasted very long

It was not possible to go to him very often—his boots lasted terribly, having something beyond the temporary, some essence of boot stitched into them.

One went in, not as into most shops, but restfully, as one enters a church, and sitting on the single wooden chair, waited. A guttural sound, and the tip-tap of his slippers beating the narrow wooden stairs and he would stand before one without coat, a little bent, in leather apron, with sleeves turned back, blinking—as if awakened from some dream of boots.

And I would say, “How do you do, Mr Gessler? Could you make me a pair of Russian-leather boots?”

Without a word he would leave me retiring whence he came, or into the other portion of the shop, and I would continue to rest in the wooden chair inhaling the incense of his trade. Soon he would come back, holding in his hand a piece of gold-brown leather. With eyes fixed on it he would remark, “What a beaudiful biece!” When I too had admired it, he would speak again. “When do you wand dem?” And I would answer, “Oh! As soon as you conveniently can.” And he would say, “Tomorrow fordnighd?” Or if he were his elder brother: “I will ask my brudder.”

incense: The smell of leather is compared to the smell of incense in a church.

“What a beautiful piece!”

“When do you want them?”

“fortnight”

“brother”

Then I would murmur, ‘’Thank you! Good morning, Mr Gessler.” “Good morning’” he would reply, still looking at the leather in his hand. And as I moved to the door, I would hear the tip-tap

of his slippers going up the stairs: to his

dream of boots.

I cannot forget that day on which I had occasion to say to him, “Mr Gessler, that last pair of boots creaked, you know.”

He looked at me for a time without replying, as if expecting me to withdraw or qualify the statement, then said,“ld shouldn’d’ave greaked.’’

“It did, I’m afraid.”

“You god dem wed before dey found demselves.”

“I don’t think so.”

“At that he lowered his eyes, as if hunting for memory of those boots and I felt sorry I had mentioned this grave thing. “Zend dem back,” he said, “I will look at dem.”

“Zome boods,” he continued slowly, “are bad from birdt. If I can do noding wid dem I take dem off your bill.”

Once (once only) I went absent-mindedly into his shop in a pair of boots bought in an emergency at some large firm. He took my order without showing me any leather and I could feel his eyes penetrating the inferior covering of my foot. At last he said, “Dose are nod my boods.”

The tone was not one of anger, nor of sorrow, not even of contempt, but there was in it something quiet that froze the blood. He put his hand down and pressed a finger on the place where the left boot was not quite comfortable.

“It shouldn’t

have creaked.”

“You got them wet before they found themselves.”

“Send them back. I will look at them”

“Some boots are bad from birth. If I can do nothing with them, I take them off your bill.”

“Those are not my boots.”

“It hurts you there. Those big firms have no self- respect.”

“Id ’urds’ you dere,” he said, “Dose big virms ’ave no self-respect.” And then, as if something had given way within him, he spoke long and bitterly. It was the only time I ever heard him discuss the conditions and hardships of his trade.

“Dey get id all,” he said, “dey get id by advertisement, nod by work. Dey take id away from us, who lofe our boods. Id gomes to dis—bresently I haf no work. Every year id gets less. You will see.” And looking at his lined face I saw things I had never noticed before, bitter things and bitter struggle and what a lot of grey hairs there seemed suddenly in his red beard!

As best I could, I explained the circumstances of those ill-omened boots. But his face and voice made so deep an impression that during the next few minutes I ordered many pairs. They lasted longer than ever. And I was not able to go to him for nearly two years.

It was many months before my next visit to his shop. This time it appeared to be his elder brother, handling a piece of leather.

“Well, Mr Gessler,” I said, “how are you?” He came close, and peered at me. “I am breddy well,” he said slowly “but my elder brudder

is dead.”

“They get it all. They get it by advertisement, not by work. They take it away from us, who love our boots. It comes to this — presently I have no work. Every year it gets less.”

“I am pretty well, but my elder brother is dead.”

“Do you want any boots?”

“It’s a beautiful piece.”

And I saw that it was indeed himself but how aged and wan! And never before had I heard him mention his brother. Much shocked, I murmured, “Oh! I am sorry!”

“Yes,” he answered, “he was a good man, he made a good bood. But he is dead.” And he touched the top of his head, where the hair had suddenly gone as thin as it had been on that of his poor brother, to indicate, I suppose, the cause of his death. “Do you wand any boods?” And he held up the leather in his hand. “ld’s a beaudiful biece.”

I ordered several pairs. It was very long before they came—but they were better than ever. One simply could not wear them out. And soon after that I went abroad.

It was over a year before I was again in London. And the first shop I went to was my old friend’s. I had left a man of sixty; I came back to one of seventy-five, pinched and worn, who genuinely, this time, did not at first know me.

“Do you wand any boods?” he said. “I can make dem quickly; id is a zlack dime.”

I answered, “Please, please! I want boots all around—every kind.”

I had given those boots up when one evening they came. One by one I tried them on. In shape and fit, in finish and quality of leather they were the best he had ever made. I flew downstairs, wrote a cheque and posted it at once with my own hand.

A week later, passing the little street, I thought I would go in and tell him how splendidly the new boots fitted. But when I came to where his shop had been, his name was gone.

“I can make them quickly; it is a slack time.”

given ... up: thought they would never come

I went in very much disturbed. In the shop, there was a young man with an English face.

“Mr Gessler in?” I said.

“No, sir,” he said. “No, but we can attend to anything with pleasure. We’ve taken the shop over.”

“Yes. yes,” I said, “but Mr Gessler?”

“Oh!” he answered, “dead.”

“Dead! But I only received these boots from him last Wednesday week.”

“Ah!” he said, “poor old man starved himself. Slow starvation, the doctor called it! You see he went to work in such a way! Would keep the shop on; wouldn’t have a soul touch his boots except himself. When he got an order, it took him such a time. People won’t wait. He lost everybody. And there he’d sit, going on and on. I will say that for him—not a man in London made a better boot. But look at the competition! He never advertised! Would have the best leather too, and do it all himself. Well, there it is. What could you expect with his ideas?”

“But starvation!”

“That may be a bit flowery, as the saying is—but I know myself he was sitting over his boots day and night, to the very last you see, I used to watch him. Never gave himself time to eat; never had a penny in the house. All went in rent and leather. How he lived so long I don’t know. He regularly let his fire go out. He was a character. But he made good boots.”

“Yes,” I said, “he made good boots.”

John Galsworthy

[simplified and abridged]

Working with the Text

Answer the following questions.

1. What was the author’s opinion about Mr Gessler as a bootmaker?

2. Why did the author visit the shop so infrequently?

3. What was the effect on Mr Gessler of the author’s remark about a certain pair of boots?

4. What was Mr Gessler’s complaint against “big firms”?

5. Why did the author order so many pairs of boots? Did he really need them?

Working with Language

I. Study the following phrases and their meanings. Use them appropriately to complete the sentences that follow.

look after: take care of

look down on: disapprove or regard as inferior

look in (on someone): make a short visit

look into: investigate

look out: be careful

look up: improve

look up to: admire

(i) After a very long spell of heat, the weather is  at last.

at last.

(ii) We have no right to  people who do small jobs.

people who do small jobs.

(iii) Nitin has always  his uncle, who is a self-made man.

his uncle, who is a self-made man.

(iv) The police are  the matter thoroughly.

the matter thoroughly.

(v) If you want to go out, I will  the children for you.

the children for you.

(vi) I promise to  on your brother when I visit Lucknow next.

on your brother when I visit Lucknow next.

(vi)  when you are crossing the main road.

when you are crossing the main road.

2. Read the following sets of words loudly and clearly.

cot — coat

cost — coast

tossed — toast

got — goat

rot — rote

blot — bloat

knot — note

3. Each of the following words contains the sound ‘sh’ (as in shine) in the beginning or in the middle or at the end. First speak out all the words clearly. Then arrange the words in three groups in the table on page 80.

sheep trash marsh fashion

anxious shriek shore fish

portion ashes sure nation

shoe pushing polish moustache

initial medial final

4. In each of the following words ‘ch’ represents the same consonant sound as in ‘chair’. The words on the left have this sound initially. Those on the right have it finally. Speak each word clearly.

choose bench

child march

cheese peach

chair wretch

charming research

Underline the letters representing this sound in each of the following words.

(i) feature (iv) reaching (vii) riches

(ii) archery (v) nature (viii) batch

(iii) picture (vi) matches (ix) church

Speaking

1. Do you think Mr Gessler was a failure as a bootmaker or as a competitive businessman?

2. What is the significance of the title? To whom or to what does it refer?

3. • Notice the way Mr Gessler speaks English. His English is influenced by his mother tongue. He speaks English with an accent.

• When Mr Gessler speaks, p,t,k, sound like b,d,g. Can you say these words as Mr Gessler would say them?

It comes and never stops. Does it bother me? Not at all. Ask my brother, please.

4. Speak to five adults in your neighbourhood. Ask them the following questions (in any language they are comfortable in). Then come back and share your findings with the class.

(i) Do they buy their provisions packed in plastic packets at a big store, or loose, from a smaller store near their house?

(ii) Where do they buy their footwear? Do they buy branded footwear, or footwear made locally? What reasons do they have for their preference?

(iii) Do they buy ready-made clothes, or buy cloth and get their clothes stitched by a tailor? Which do they think is better?

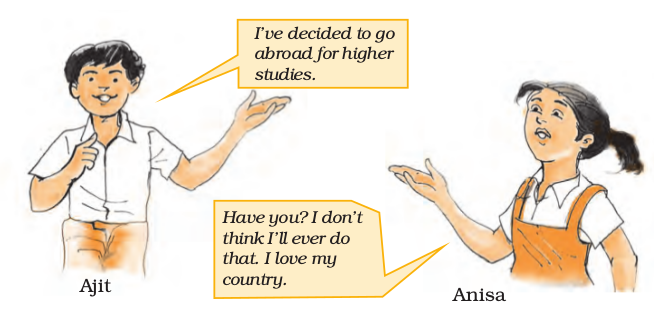

5. Look at the picture.

Let pairs of students talk to each other about leaving the country. One student repeats Ajit’s statement. The other gives a reason for not agreeing with Ajit. The sentence openings given below should be used.

• If I leave this country, I’ll miss...

• There are some things which you can get only here, for example...

• There are some special days I’ll miss, particularly...

• Most of all I’ll miss...because...

• I think it’s impossible for me to leave my country because...

• How can you leave your own country except when...?

• Depends on one’s intention. I can’t leave for good because...

• Maybe for a couple of years...

Writing

I. Based on the following points write a story.

• Your aunt has gone to her mother’s house.

• Your uncle does his cooking.

• He is absent-minded.

• He puts vegetables on the stove.

• He begins to clean his bicycle outside.

• The neighbour calls out saying something is burning.

• Your uncle rushes to the kitchen.

• To save vegetables, he puts some oil on them.

• Unfortunately, it’s machine oil, not cooking oil.

• What do you think happens to the vegetables?

Begin like this:

Last month my aunt decided to visit her parents...

Trees

Take a few minutes to tell one another the names of trees that you know or have heard of. Mention the things trees give us. Then read this poem about trees.

Trees are for birds.

Trees are for children.

Trees are to make tree houses in.

Trees are to swing swings on.

Trees are for the wind to blow through.

Trees are to hide behind in ‘Hide and Seek.’

Trees are to have tea parties under.

Trees are for kites to get caught in.

Trees are to make cool shade in summer.

Trees are to make no shade in winter.

Trees are for apples to grow on, and pears;

Trees are to chop down and call, “TIMBER-R-R!”

Trees make mothers say,

“What a lovely picture to paint!”

Trees make fathers say,

“What a lot of leaves to rake this fall !”

Shirley Bauer

Working with the Poem

1. What are the games or human activities which use trees, or in which trees also ‘participate’?

2. (i) “Trees are to make no shade in winter.” What does this mean? (Contrast this line with the line immediately before it.)

(ii) “Trees are for apples to grow on, or pears.” Do you agree that one purpose of a tree is to have fruit on it? Or do you think this line is humorous?

3. With the help of your partner, try to rewrite some lines in the poem, or add new ones of your own as in the following examples.

Trees are for birds to build nests in.

Trees are for people to sit under.

Now try to compose a similar poem about water, or air.

‘Mangrove’ is the name commonly used for varieties of shrubs or trees growing in the muddy swamps of tropical coasts and estuaries. Mangroves produce tangled roots that grow above the ground. They produce new trunks and thus rapidly form a dense growth. Mangrove timber is impervious to water and is resistant to marine worms.