Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Number Systems

1.1 Introduction

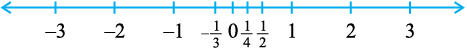

In your earlier classes, you have learnt about the number line and how to represent various types of numbers on it (see Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1 :The number line

Just imagine you start from zero and go on walking along this number line in the positive direction. As far as your eyes can see, there are numbers, numbers and numbers!

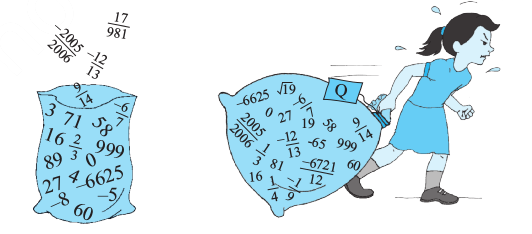

Fig. 1.2

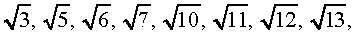

Now suppose you start walking along the number line, and collecting some of the numbers. Get a bag ready to store them!

You might begin with picking up only natural numbers like 1, 2, 3, and so on. You know that this list goes on for ever. (Why is this true?) So, now your bag contains infinitely many natural numbers! Recall that we denote this collection by the symbol N

You might begin with picking up only natural numbers like 1, 2, 3, and so on. You know that this list goes on for ever. (Why is this true?) So, now your bag contains infinitely many natural numbers! Recall that we denote this collection by the symbol N

Now turn and walk all the way back, pick up zero and put it into the bag. You now have the collection of whole numbers which is denoted by the symbol W.

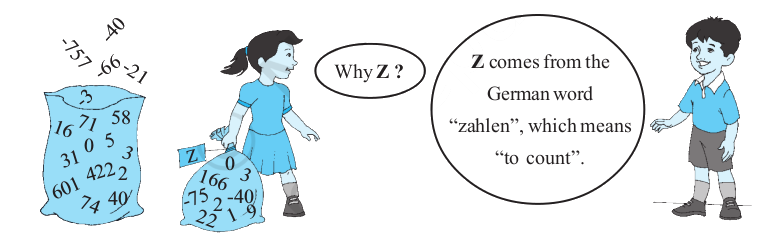

Now, stretching in front of you are many, many negative integers. Put all the negative integers into your bag. What is your new collection? Recall that it is the collection of all integers, and it is denoted by the symbol Z.

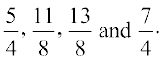

Are there some numbers still left on the line? Of course! There are numbers like  , or even

, or even  . If you put all such numbers also into the bag, it will now be the collection of rational numbers. The collection of rational numbers is denoted by Q. ‘Rational’ comes from the word ‘ratio’, and Q comes from the word ‘quotient’.

. If you put all such numbers also into the bag, it will now be the collection of rational numbers. The collection of rational numbers is denoted by Q. ‘Rational’ comes from the word ‘ratio’, and Q comes from the word ‘quotient’.

You may recall the definition of rational numbers:

A number ‘r’ is called a rational number, if it can be written in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0. (Why do we insist that q ≠ 0?)

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0. (Why do we insist that q ≠ 0?)

Notice that all the numbers now in the bag can be written in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0. For example, –25 can be written as

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0. For example, –25 can be written as  here p = –25 and q = 1. Therefore, the rational numbers also include the natural numbers, whole numbers and integers.

here p = –25 and q = 1. Therefore, the rational numbers also include the natural numbers, whole numbers and integers.

You also know that the rational numbers do not have a unique representation in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0. For example,

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0. For example,  =

=  =

=  =

=  =

=  , and so on. These are equivalent rational numbers (or fractions). However, when we say that

, and so on. These are equivalent rational numbers (or fractions). However, when we say that  is a rational number, or when we represent

is a rational number, or when we represent  on the number line, we assume that q ≠ 0 and that p and q have no common factors other than 1 (that is, p and q are co-prime). So, on the number line, among the infinitely many fractions equivalent to

on the number line, we assume that q ≠ 0 and that p and q have no common factors other than 1 (that is, p and q are co-prime). So, on the number line, among the infinitely many fractions equivalent to  , we will choose

, we will choose  to represent all of them.

to represent all of them.

Now, let us solve some examples about the different types of numbers, which you have studied in earlier classes.

Example 1 : Are the following statements true or false? Give reasons for your answers.

(i) Every whole number is a natural number.

(ii) Every integer is a rational number.

(iii) Every rational number is an integer.

Solution : (i) False, because zero is a whole number but not a natural number.

(ii) True, because every integer m can be expressed in the form  , and so it is a rational number.

, and so it is a rational number.

(iii) False, because  is not an integer.

is not an integer.

Example 2 : Find five rational numbers between 1 and 2.

We can approach this problem in at least two ways.

Solution 1 : Recall that to find a rational number between r and s, you can add r and s and divide the sum by 2, that is  lies between r and s. So,

lies between r and s. So,  is a number between 1 and 2. You can proceed in this manner to find four more rational numbers between 1 and 2. These four numbers are

is a number between 1 and 2. You can proceed in this manner to find four more rational numbers between 1 and 2. These four numbers are

Solution 2 : The other option is to find all the five rational numbers in one step. Since we want five numbers, we write 1 and 2 as rational numbers with denominator 5 + 1, i.e., 1 =  and 2 =

and 2 =  . Then you can check that

. Then you can check that  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are all rational numbers between 1 and 2. So, the five numbers are

are all rational numbers between 1 and 2. So, the five numbers are  .

.

Remark: Notice that in Example 2, you were asked to find five rational numbers between 1 and 2. But, you must have realised that in fact there are infinitely many rational numbers between 1 and 2. In general, there are infinitely many rational numbers between any two given rational numbers.

Let us take a look at the number line again. Have you picked up all the numbers? Not, yet. The fact is that there are infinitely many more numbers left on the number line! There are gaps in between the places of the numbers you picked up, and not just one or two but infinitely many. The amazing thing is that there are infinitely many numbers lying between any two of these gaps too!

So we are left with the following questions:

1. What are the numbers, that are left on the number line, called?

2. How do we recognise them? That is, how do we distinguish them from the rationals (rational numbers)?

These questions will be answered in the next section.

EXERCISE 1.1

1. Is zero a rational number? Can you write it in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0?

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0?

2. Find six rational numbers between 3 and 4.

3. Find five rational numbers between  and

and  .

.

4. State whether the following statements are true or false. Give reasons for your answers.

(i) Every natural number is a whole number.

(ii) Every integer is a whole number.

(iii) Every rational number is a whole number.

1.2 Irrational Numbers

We saw, in the previous section, that there may be numbers on the number line that are not rationals. In this section, we are going to investigate these numbers. So far, all the numbers you have come across, are of the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0. So, you may ask: are there numbers which are not of this form? There are indeed such numbers.

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0. So, you may ask: are there numbers which are not of this form? There are indeed such numbers.

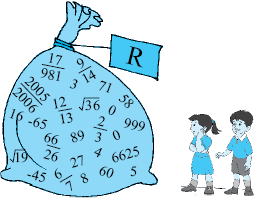

The Pythagoreans in Greece, followers of the famous mathematician and philosopher Pythagoras, were the first to discover the numbers which were not rationals, around 400 BC. These numbers are called irrational numbers (irrationals), because they cannot be written in the form of a ratio of integers. There are many myths surrounding the discovery of irrational numbers by the Pythagorean, Hippacus of Croton.

Fig. 1.3

In all the myths, Hippacus has an unfortunate end, either for discovering that  is irrational or for disclosing the secret about

is irrational or for disclosing the secret about  to people outside the secret Pythagorean sect!

to people outside the secret Pythagorean sect!

Let us formally define these numbers.

A number ‘s’ is called irrational, if it cannot be written in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

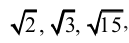

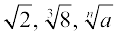

You already know that there are infinitely many rationals. It turns out that there are infinitely many irrational numbers too. Some examples are:

π, 0.10110111011110...

π, 0.10110111011110...

Remark: Recall that when we use the symbol  , we assume that it is the positive square root of the number. So

, we assume that it is the positive square root of the number. So  = 2, though both 2 and –2 are square roots of 4.

= 2, though both 2 and –2 are square roots of 4.

Some of the irrational numbers listed above are familiar to you. For example, you have already come across many of the square roots listed above and the number π.

The Pythagoreans proved that  is irrational. Later in approximately 425 BC, Theodorus of Cyrene showed that

is irrational. Later in approximately 425 BC, Theodorus of Cyrene showed that

and

and  are also irrationals. Proofs of irrationality of

are also irrationals. Proofs of irrationality of  ,

,  ,

,  , etc., shall be discussed in Class X. As to π, it was known to various cultures for thousands of years, it was proved to be irrational by Lambert and Legendre only in the late 1700s. In the next section, we will discuss why 0.10110111011110... and π are irrational.

, etc., shall be discussed in Class X. As to π, it was known to various cultures for thousands of years, it was proved to be irrational by Lambert and Legendre only in the late 1700s. In the next section, we will discuss why 0.10110111011110... and π are irrational.

Let us return to the questions raised at the end of the previous section. Remember the bag of rational numbers. If we now put all irrational numbers into the bag, will there be any number left on the number line? The answer is no! It turns out that the collection of all rational numbers and irrational numbers together make up what we call the collection of real numbers,

Let us return to the questions raised at the end of the previous section. Remember the bag of rational numbers. If we now put all irrational numbers into the bag, will there be any number left on the number line? The answer is no! It turns out that the collection of all rational numbers and irrational numbers together make up what we call the collection of real numbers,

which is denoted by R. Therefore, a real number is either rational or irrational. So, we can say that every real number is represented by a unique point on the number line. Also, every point on the number line represents a unique real number. This is why we call the number line, the real number line.

Fig. 1.4

In the 1870s two German mathematicians, Cantor and Dedekind, showed that : Corresponding to every real number, there is a point on the real number line, and corresponding to every point on the number line, there exists a unique real number.

Let us see how we can locate some of the irrational numbers on the number line.

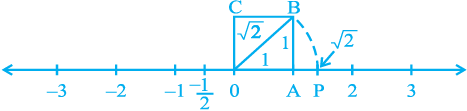

Example 3 : Locate  on the number line.

on the number line.

Solution : It is easy to see how the Greeks might have discovered  . Consider a square OABC, with each side 1 unit in length (see Fig. 1.6). Then you can see by the Pythagoras theorem that

. Consider a square OABC, with each side 1 unit in length (see Fig. 1.6). Then you can see by the Pythagoras theorem that

OB =  . How do we represent

. How do we represent  on the number line?

on the number line?

This is easy. Transfer Fig. 1.6 onto the number line making sure that the vertex O coincides with zero (see Fig. 1.7).

Fig. 1.7

We have just seen that OB =  . Using a compass with centre O and radius OB, draw an arc intersecting the number line at the point P. Then P corresponds to

. Using a compass with centre O and radius OB, draw an arc intersecting the number line at the point P. Then P corresponds to  on the number line.

on the number line.

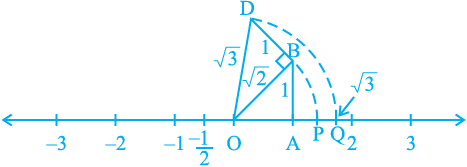

Example 4 : Locate  on the number line.

on the number line.

Solution : Let us return to Fig. 1.7.

Fig. 1.8

Construct BD of unit length perpendicular to OB (as in Fig. 1.8). Then using the Pythagoras theorem, we see that OD =  . Using a compass, with centre O and radius OD, draw an arc which intersects the number line at the point Q. Then Q corresponds to

. Using a compass, with centre O and radius OD, draw an arc which intersects the number line at the point Q. Then Q corresponds to  .

.

In the same way, you can locate  for any positive integer n, after

for any positive integer n, after  has been located.

has been located.

EXERCISE 1.2

1. State whether the following statements are true or false. Justify your answers.

(i) Every irrational number is a real number.

(ii) Every point on the number line is of the form  , where m is a natural number.

, where m is a natural number.

(iii) Every real number is an irrational number.

2. Are the square roots of all positive integers irrational? If not, give an example of the square root of a number that is a rational number.

3. Show how  can be represented on the number line.

can be represented on the number line.

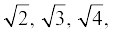

4. Classroom activity (Constructing the ‘square root spiral’) : Take a large sheet of paper and construct the ‘square root spiral’ in the following fashion. Start with a point O and draw a line segment OP1 of unit length. Draw a line segment P1P2 perpendicular to OP1 of unit length (see Fig. 1.9). Now draw a line segment P2P3 perpendicular to OP2. Then draw a line segment P3P4 perpendicular to OP3. Continuing in this manner, you can get the line segment Pn–1Pn by drawing a line segment of unit length perpendicular to OPn–1. In this manner, you will have created the points P2, P3,...., Pn,... ., and joined them to create a beautiful spiral depicting  ...

...

Fig. 1.9 : Constructing square root spiral

1.3 Real Numbers and their Decimal Expansions

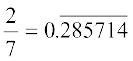

In this section, we are going to study rational and irrational numbers from a different point of view. We will look at the decimal expansions of real numbers and see if we can use the expansions to distinguish between rationals and irrationals. We will also explain how to visualise the representation of real numbers on the number line using their decimal expansions. Since rationals are more familiar to us, let us start with them. Let us take three examples :  .

.

Pay special attention to the remainders and see if you can find any pattern.

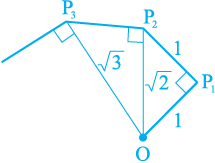

Example 5 : Find the decimal expansions of,

and

and  .

.

Solution :

What have you noticed? You should have noticed at least three things:

(i) The remainders either become 0 after a certain stage, or start repeating themselves.

(ii) The number of entries in the repeating string of remainders is less than the divisor (in  one number repeats itself and the divisor is 3, in

one number repeats itself and the divisor is 3, in  there are six entries 326451 in the repeating string of remainders and 7 is the divisor).

there are six entries 326451 in the repeating string of remainders and 7 is the divisor).

(iii) If the remainders repeat, then we get a repeating block of digits in the quotient (for  , 3 repeats in the quotient and for

, 3 repeats in the quotient and for  , we get the repeating block 142857 in the quotient).

, we get the repeating block 142857 in the quotient).

Although we have noticed this pattern using only the examples above, it is true for all rationals of the form  (q ≠ 0). On division of p by q, two main things happen – either the remainder becomes zero or never becomes zero and we get a repeating string of remainders. Let us look at each case separately.

(q ≠ 0). On division of p by q, two main things happen – either the remainder becomes zero or never becomes zero and we get a repeating string of remainders. Let us look at each case separately.

Case (i) : The remainder becomes zero

In the example of  , we found that the remainder becomes zero after some steps and the decimal expansion of

, we found that the remainder becomes zero after some steps and the decimal expansion of  = 0.875. Other examples are

= 0.875. Other examples are  = 0.5,

= 0.5,  = 2.556. In all these cases, the decimal expansion terminates or ends after a finite number of steps. We call the decimal expansion of such numbers terminating.

= 2.556. In all these cases, the decimal expansion terminates or ends after a finite number of steps. We call the decimal expansion of such numbers terminating.

Case (ii) : The remainder never becomes zero

In the examples of  and

and  , we notice that the remainders repeat after a certain stage forcing the decimal expansion to go on for ever. In other words, we have a repeating block of digits in the quotient. We say that this expansion is non-terminating recurring. For example,

, we notice that the remainders repeat after a certain stage forcing the decimal expansion to go on for ever. In other words, we have a repeating block of digits in the quotient. We say that this expansion is non-terminating recurring. For example,  = 0.3333... and

= 0.3333... and  = 0.142857142857142857...

= 0.142857142857142857...

The usual way of showing that 3 repeats in the quotient of  is to write it as

is to write it as  . Similarly, since the block of digits 142857 repeats in the quotient of

. Similarly, since the block of digits 142857 repeats in the quotient of  , we write

, we write  as

as  , where the bar above the digits indicates the block of digits that repeats. Also 3.57272... can be written as

, where the bar above the digits indicates the block of digits that repeats. Also 3.57272... can be written as  . So, all these examples give us non-terminating recurring (repeating) decimal expansions.

. So, all these examples give us non-terminating recurring (repeating) decimal expansions.

Thus, we see that the decimal expansion of rational numbers have only two choices: either they are terminating or non-terminating recurring.

Now suppose, on the other hand, on your walk on the number line, you come across a number like 3.142678 whose decimal expansion is terminating or a number like 1.272727... that is,  , whose decimal expansion is non-terminating recurring, can you conclude that it is a rational number? The answer is yes!

, whose decimal expansion is non-terminating recurring, can you conclude that it is a rational number? The answer is yes!

We will not prove it but illustrate this fact with a few examples. The terminating cases are easy.

Example 6 : Show that 3.142678 is a rational number. In other words, express 3.142678 in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

Solution : We have 3.142678 =  , and hence is a rational number.

, and hence is a rational number.

Now, let us consider the case when the decimal expansion is non-terminating recurring.

Example 7 : Show that 0.3333... =  can be expressed in the form

can be expressed in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

Solution : Since we do not know what  is , let us call it ‘x’ and so

is , let us call it ‘x’ and so

x = 0.3333...

Now here is where the trick comes in. Look at

10 x = 10 × (0.333...) = 3.333...

Now, 3.3333... = 3 + x, since x = 0.3333...

Therefore, 10 x = 3 + x

Solving for x, we get

9x = 3, i.e., x =

Example 8 : Show that 1.272727... =  can be expressed in the form

can be expressed in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

Solution : Let x = 1.272727... Since two digits are repeating, we multiply x by 100 to get

100 x = 127.2727...

So, 100 x = 126 + 1.272727... = 126 + x

Therefore, 100 x – x = 126, i.e., 99 x = 126

i.e., x =

You can check the reverse that  =

=  .

.

Example 9 : Show that 0.2353535... =  can be expressed in the form

can be expressed in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

Solution : Let x =  . Over here, note that 2 does not repeat, but the block 35 repeats. Since two digits are repeating, we multiply x by 100 to get

. Over here, note that 2 does not repeat, but the block 35 repeats. Since two digits are repeating, we multiply x by 100 to get

100 x = 23.53535...

So, 100 x = 23.3 + 0.23535... = 23.3 + x

Therefore, 99 x = 23.3

i.e., 99 x =  , which gives x =

, which gives x =

You can also check the reverse that  =

=  .

.

So, every number with a non-terminating recurring decimal expansion can be expressed in the form  (q ≠ 0), where p and q are integers. Let us summarise our results in the following form :

(q ≠ 0), where p and q are integers. Let us summarise our results in the following form :

The decimal expansion of a rational number is either terminating or non-terminating recurring. Moreover, a number whose decimal expansion is terminating or non-terminating recurring is rational.

So, now we know what the decimal expansion of a rational number can be. What about the decimal expansion of irrational numbers? Because of the property above, we can conclude that their decimal expansions are non-terminating non-recurring.

So, the property for irrational numbers, similar to the property stated above for rational numbers, is

The decimal expansion of an irrational number is non-terminating non-recurring. Moreover, a number whose decimal expansion is non-terminating non-recurring is irrational.

Recall s = 0.10110111011110... from the previous section. Notice that it is non-terminating and non-recurring. Therefore, from the property above, it is irrational. Moreover, notice that you can generate infinitely many irrationals similar to s.

What about the famous irrationals  and π? Here are their decimal expansions up to a certain stage.

and π? Here are their decimal expansions up to a certain stage.

= 1.4142135623730950488016887242096...

= 1.4142135623730950488016887242096...

π = 3.14159265358979323846264338327950...

(Note that, we often take  as an approximate value for π, but π ≠

as an approximate value for π, but π ≠  .)

.)

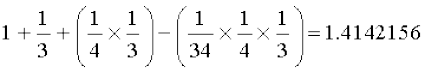

Over the years, mathematicians have developed various techniques to produce more and more digits in the decimal expansions of irrational numbers. For example, you might have learnt to find digits in the decimal expansion of  by the division method. Interestingly, in the Sulbasutras (rules of chord), a mathematical treatise of the Vedic period (800 BC - 500 BC), you find an approximation of

by the division method. Interestingly, in the Sulbasutras (rules of chord), a mathematical treatise of the Vedic period (800 BC - 500 BC), you find an approximation of  as follows:

as follows:

=

=

Notice that it is the same as the one given above for the first five decimal places. The history of the hunt for digits in the decimal expansion of π is very interesting.

The Greek genius Archimedes was the first to compute digits in the decimal expansion of π. He showed 3.140845 < π < 3.142857. Aryabhatta (476 – 550 AD), the great Indian mathematician and astronomer, found the value of π correct to four decimal places (3.1416). Using high speed computers and advanced algorithms, π has been computed to over 1.24 trillion decimal places!

Archimedes (287 BCE – 212 BCE)

Fig. 1.10

Now, let us see how to obtain irrational numbers.

Example 10 : Find an irrational number between  and

and  .

.

Solution : We saw that  =

=  . So, you can easily calculate

. So, you can easily calculate  . To find an irrational number between

. To find an irrational number between  and

and  , we find a number which is

, we find a number which is

non-terminating non-recurring lying between them. Of course, you can find infinitely many such numbers.

An example of such a number is 0.150150015000150000...

EXERCISE 1.3

1. Write the following in decimal form and say what kind of decimal expansion each has :

(i)  (ii)

(ii)  (iii)

(iii)

(iv)  (v)

(v)  (vi)

(vi)

2. You know that  =

=  . Can you predict what the decimal expansions of

. Can you predict what the decimal expansions of  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  are, without actually doing the long division? If so, how?

are, without actually doing the long division? If so, how?

[Hint : Study the remainders while finding the value of  carefully.]

carefully.]

3. Express the following in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

(i)  (ii)

(ii)  (iii)

(iii)

4. Express 0.99999 .... in the form  . Are you surprised by your answer? With your teacher and classmates discuss why the answer makes sense.

. Are you surprised by your answer? With your teacher and classmates discuss why the answer makes sense.

5. What can the maximum number of digits be in the repeating block of digits in the decimal expansion of  ? Perform the division to check your answer.

? Perform the division to check your answer.

6. Look at several examples of rational numbers in the form  (q ≠ 0), where p and q are integers with no common factors other than 1 and having terminating decimal representations (expansions). Can you guess what property q must satisfy?

(q ≠ 0), where p and q are integers with no common factors other than 1 and having terminating decimal representations (expansions). Can you guess what property q must satisfy?

7. Write three numbers whose decimal expansions are non-terminating non-recurring.

8. Find three different irrational numbers between the rational numbers  and

and  .

.

9. Classify the following numbers as rational or irrational :

(i)  (ii)

(ii)  (iii) 0.3796

(iii) 0.3796

(iv) 7.478478... (v) 1.101001000100001...

1.4 Representing Real Numbers on the Number Line

In the previous section, you have seen that any real number has a decimal expansion. This helps us to represent it on the number line. Let us see how.

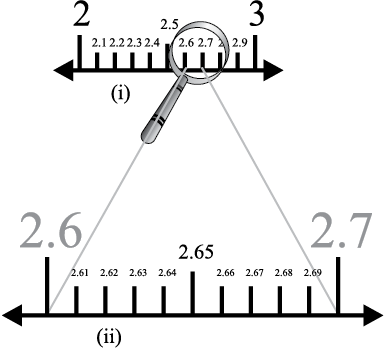

Suppose we want to locate 2.665 on the number line. We know that this lies between 2 and 3.

So, let us look closely at the portion of the number line between 2 and 3. Suppose we divide this into 10 equal parts and mark each point of division as in Fig. 1.11 (i). Then the first mark to the right of 2 will represent 2.1, the second 2.2, and so on. You might be finding some difficulty in observing these points of division between 2 and 3 in Fig. 1.11 (i).

Fig. 1.11

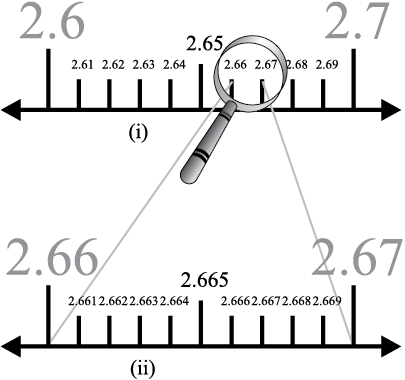

To have a clear view of the same, you may take a magnifying glass and look at the portion between 2 and 3. It will look like what you see in Fig. 1.11 (ii). Now, 2.665 lies between 2.6 and 2.7. So, let us focus on the portion between 2.6 and 2.7 [See Fig. 1.12(i)]. We imagine to divide this again into ten equal parts. The first mark will represent 2.61, the next 2.62, and so on. To see this clearly, we magnify this as shown in Fig. 1.12 (ii).

Fig. 1.12

Again, 2.665 lies between 2.66 and 2.67. So, let us focus on this portion of the number line [see Fig. 1.13(i)] and imagine to divide it again into ten equal parts. We magnify it to see it better, as in Fig. 1.13 (ii). The first mark represents 2.661, the next one represents 2.662, and so on. So, 2.665 is the 5th mark in these subdivisions.

Fig. 1.13

We call this process of visualisation of representation of numbers on the number line, through a magnifying glass, as the process of successive magnification.

So, we have seen that it is possible by sufficient successive magnifications to visualise the position (or representation) of a real number with a terminating decimal expansion on the number line.

Let us now try and visualise the position (or representation) of a real number with a non-terminating recurring decimal expansion on the number line. We can look at appropriate intervals through a magnifying glass and by successive magnifications visualise the position of the number on the number line.

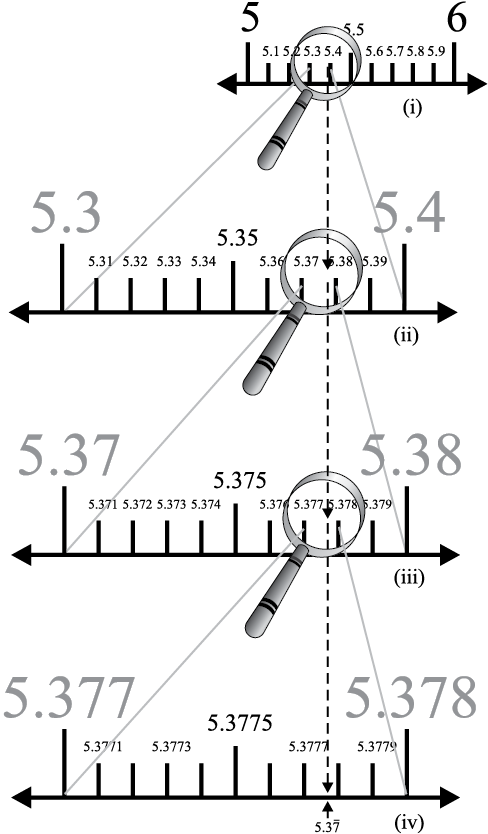

Example 11 : Visualize the representation of  on the number line upto 5 decimal places, that is, up to 5.37777.

on the number line upto 5 decimal places, that is, up to 5.37777.

Solution : Once again we proceed by successive magnification, and successively decrease the lengths of the portions of the number line in which  is located. First, we see that

is located. First, we see that  is located between 5 and 6. In the next step, we locate

is located between 5 and 6. In the next step, we locate  between 5.3 and 5.4. To get a more accurate visualization of the representation, we divide this portion of the number line into 10 equal parts and use a magnifying glass to visualize that

between 5.3 and 5.4. To get a more accurate visualization of the representation, we divide this portion of the number line into 10 equal parts and use a magnifying glass to visualize that  lies between 5.37 and 5.38. To visualize

lies between 5.37 and 5.38. To visualize  more accurately, we again divide the portion between 5.37 and 5.38 into ten equal parts and use a magnifying glass to visualize that

more accurately, we again divide the portion between 5.37 and 5.38 into ten equal parts and use a magnifying glass to visualize that  lies between 5.377 and 5.378. Now to visualize

lies between 5.377 and 5.378. Now to visualize  still more accurately, we divide the portion between 5.377 an 5.378 into 10 equal parts, and visualize the representation of

still more accurately, we divide the portion between 5.377 an 5.378 into 10 equal parts, and visualize the representation of  as in Fig. 1.14 (iv). Notice that

as in Fig. 1.14 (iv). Notice that  is located closer to 5.3778 than to 5.3777 [see Fig 1.14 (iv)].

is located closer to 5.3778 than to 5.3777 [see Fig 1.14 (iv)].

s

s

Fig. 1.14

Remark: We can proceed endlessly in this manner, successively viewing through a magnifying glass and simultaneously imagining the decrease in the length of the portion of the number line in which  is located. The size of the portion of the line we specify depends on the degree of accuracy we would like for the visualisation of the position of the number on the number line.

is located. The size of the portion of the line we specify depends on the degree of accuracy we would like for the visualisation of the position of the number on the number line.

You might have realised by now that the same procedure can be used to visualise a real number with a non-terminating non-recurring decimal expansion on the number line.

In the light of the discussions above and visualisations, we can again say that every real number is represented by a unique point on the number line. Further, every point on the number line represents one and only one real number.

EXERCISE 1.4

1. Visualise 3.765 on the number line, using successive magnification.

2. Visualise  on the number line, up to 4 decimal places.

on the number line, up to 4 decimal places.

1.5 Operations on Real Numbers

You have learnt, in earlier classes, that rational numbers satisfy the commutative, associative and distributive laws for addition and multiplication. Moreover, if we add, subtract, multiply or divide (except by zero) two rational numbers, we still get a rational number (that is, rational numbers are ‘closed’ with respect to addition, subtraction, multiplication and division). It turns out that irrational numbers also satisfy the commutative, associative and distributive laws for addition and multiplication. However, the sum, difference, quotients and products of irrational numbers are not always irrational. For example,  ,

, and

and  are rationals.

are rationals.

Let us look at what happens when we add and multiply a rational number with an irrational number. For example,  is irrational. What about

is irrational. What about and

and  ? Since

? Since  has a non-terminating non-recurring decimal expansion, the same is true for

has a non-terminating non-recurring decimal expansion, the same is true for  and

and  . Therefore, both

. Therefore, both  and

and  are also irrational numbers.

are also irrational numbers.

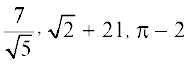

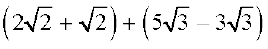

Example 12 : Check whether  ,

,  are irrational numbers or not.

are irrational numbers or not.

Solution :  = 2.236... ,

= 2.236... ,  = 1.4142..., π = 3.1415...

= 1.4142..., π = 3.1415...

Then  = 15.652...,

= 15.652...,  =

=  = 3.1304...

= 3.1304...

+ 21 = 22.4142..., π – 2 = 1.1415...

+ 21 = 22.4142..., π – 2 = 1.1415...

All these are non-terminating non-recurring decimals. So, all these are irrational numbers.

Now, let us see what generally happens if we add, subtract, multiply, divide, take square roots and even nth roots of these irrational numbers, where n is any natural number. Let us look at some examples.

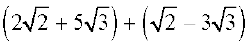

Example 13 : Add  and

and  .

.

Solution :  =

=

=

Example 14 : Multiply  by

by  .

.

Solution :  ×

×  = 6 × 2 ×

= 6 × 2 ×  ×

×  = 12 × 5 = 60

= 12 × 5 = 60

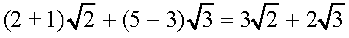

Example 15 : Divide  by

by  .

.

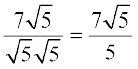

Solution :

These examples may lead you to expect the following facts, which are true:

(i) The sum or difference of a rational number and an irrational number is irrational.

(ii) The product or quotient of a non-zero rational number with an irrational number is irrational.

(iii) If we add, subtract, multiply or divide two irrationals, the result may be rational or irrational.

sWe now turn our attention to the operation of taking square roots of real numbers. Recall that, if a is a natural number, then  means b2 = a and b > 0. The same definition can be extended for positive real numbers.

means b2 = a and b > 0. The same definition can be extended for positive real numbers.

Let a > 0 be a real number. Then  = b means b2 = a and b > 0.

= b means b2 = a and b > 0.

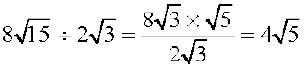

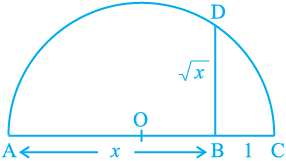

In Section 1.2, we saw how to represent  for any positive integer n on the number line. We now show how to find

for any positive integer n on the number line. We now show how to find  for any given positive real number x geometrically. For example, let us find it for x = 3.5, i.e., we find

for any given positive real number x geometrically. For example, let us find it for x = 3.5, i.e., we find  geometrically.

geometrically.

Fig. 1.15

Mark the distance 3.5 units from a fixed point A on a given line to obtain a point B such that AB = 3.5 units (see Fig. 1.15). From B, mark a distance of 1 unit and mark the new point as C. Find the mid-point of AC and mark that point as O. Draw a semicircle with centre O and radius OC. Draw a line perpendicular to AC passing through B and intersecting the semicircle at D. Then, BD =  .

.

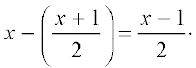

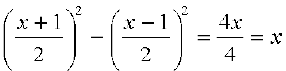

More generally, to find  , for any positive real number x, we mark B so that AB = x units, and, as in Fig. 1.16, mark C so that BC = 1 unit. Then, as we have done for the case x = 3.5, we find BD =

, for any positive real number x, we mark B so that AB = x units, and, as in Fig. 1.16, mark C so that BC = 1 unit. Then, as we have done for the case x = 3.5, we find BD =  (see Fig. 1.16). We can prove this result using the Pythagoras Theorem.

(see Fig. 1.16). We can prove this result using the Pythagoras Theorem.

Notice that, in Fig. 1.16, ∆ OBD is a right-angled triangle. Also, the radius of the circle is  units.

units.

Therefore, OC = OD = OA =  units.

units.

Now, OB =

So, by the Pythagoras Theorem, we have

BD2 = OD2 – OB2 =  .

.

This shows that BD =  .

.

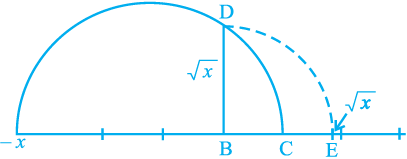

This construction gives us a visual, and geometric way of showing that  exists for all real numbers x > 0. If you want to know the position of

exists for all real numbers x > 0. If you want to know the position of  on the number line, then let us treat the line BC as the number line, with B as zero, C as 1, and so on. Draw an arc with centre B and radius BD, which intersects the number line in E

on the number line, then let us treat the line BC as the number line, with B as zero, C as 1, and so on. Draw an arc with centre B and radius BD, which intersects the number line in E

(see Fig. 1.17). Then, E represents  .

.

Fig. 1.17

We would like to now extend the idea of square roots to cube roots, fourth roots, and in general nth roots, where n is a positive integer. Recall your understanding of square roots and cube roots from earlier classes.

What is  ? Well, we know it has to be some positive number whose cube is 8, and you must have guessed

? Well, we know it has to be some positive number whose cube is 8, and you must have guessed  = 2. Let us try

= 2. Let us try  . Do you know some number b such that b5 = 243? The answer is 3. Therefore,

. Do you know some number b such that b5 = 243? The answer is 3. Therefore,  = 3.

= 3.

From these examples, can you define  for a real number a > 0 and a positive integer n?

for a real number a > 0 and a positive integer n?

Let a > 0 be a real number and n be a positive integer. Then  = b, if bn = a and

= b, if bn = a and

b > 0. Note that the symbol ‘ ’ used in

’ used in  , etc. is called the radical sign.

, etc. is called the radical sign.

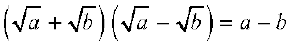

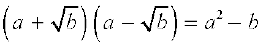

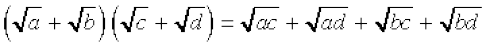

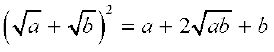

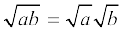

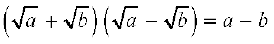

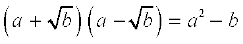

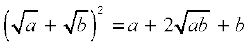

We now list some identities relating to square roots, which are useful in various ways. You are already familiar with some of these from your earlier classes. The remaining ones follow from the distributive law of multiplication over addition of real numbers, and from the identity (x + y) (x – y) = x2 – y2, for any real numbers x and y.

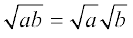

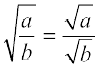

Let a and b be positive real numbers. Then

(i)  (ii)

(ii)

(iii)  (iv)

(iv)

(v)

(vi)

Let us look at some particular cases of these identities.

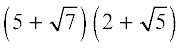

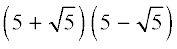

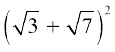

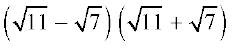

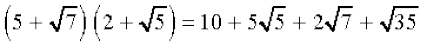

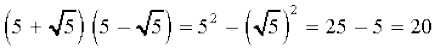

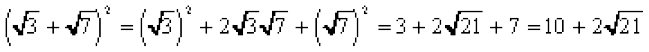

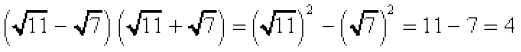

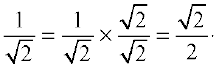

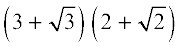

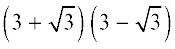

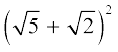

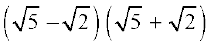

Example 16 : Simplify the following expressions:

(i)  (ii)

(ii)

(iii)  (iv)

(iv)

Solution : (i)

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

Remark : Note that ‘simplify’ in the example above has been used to mean that the expression should be written as the sum of a rational and an irrational number.

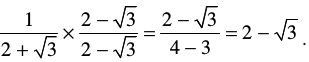

We end this section by considering the following problem. Look at  Can you tell where it shows up on the number line? You know that it is irrational. May be it is easier to handle if the denominator is a rational number. Let us see, if we can ‘rationalise’ the denominator, that is, to make the denominator into a rational number. To do so, we need the identities involving square roots. Let us see how.

Can you tell where it shows up on the number line? You know that it is irrational. May be it is easier to handle if the denominator is a rational number. Let us see, if we can ‘rationalise’ the denominator, that is, to make the denominator into a rational number. To do so, we need the identities involving square roots. Let us see how.

Example 17 : Rationalise the denominator of

Solution : We want to write  as an equivalent expression in which the denominator is a rational number. We know that

as an equivalent expression in which the denominator is a rational number. We know that  .

. is rational. We also know that multiplying

is rational. We also know that multiplying  by

by  will give us an equivalent expression, since

will give us an equivalent expression, since  = 1. So, we put these two facts together to get

= 1. So, we put these two facts together to get

In this form, it is easy to locate  on the number line. It is half way between 0 and

on the number line. It is half way between 0 and  .

.

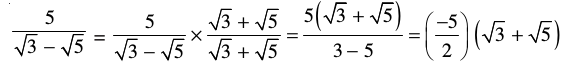

Example 18 : Rationalise the denominator of

Solution : We use the Identity (iv) given earlier. Multiply and divide  by

by  to get

to get  .

.

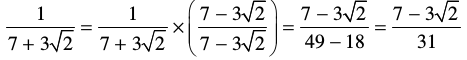

Example 19 : Rationalise the denominator of

Solution : Here we use the Identity (iii) given earlier.

So,

Example 20 : Rationalise the denominator of

Solution :

So, when the denominator of an expression contains a term with a square root (or a number under a radical sign), the process of converting it to an equivalent expression whose denominator is a rational number is called rationalising the denominator.

EXERCISE 1.5

1. Classify the following numbers as rational or irrational:

(i)  (ii)

(ii)  (iii)

(iii)

(iv)  (v) 2π

(v) 2π

2. Simplify each of the following expressions:

(i)  (ii)

(ii)

(iii)  (iv)

(iv)

3. Recall, π is defined as the ratio of the circumference (say c) of a circle to its diameter (say d). That is, π =  This seems to contradict the fact that π is irrational. How will you resolve this contradiction?

This seems to contradict the fact that π is irrational. How will you resolve this contradiction?

4. Represent  on the number line.

on the number line.

5. Rationalise the denominators of the following:

(i)  (ii)

(ii)

(iii)  (iv)

(iv)

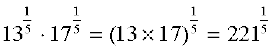

1.6 Laws of Exponents for Real Numbers

Do you remember how to simplify the following?

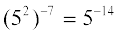

(i) 172 . 175 = (ii) (52)7 =

(iii)  = (iv) 73 . 93 =

= (iv) 73 . 93 =

Did you get these answers? They are as follows:

(i) 172 . 175 = 177 (ii) (52)7 = 514

(iii)  (iv) 73 . 93 = 633

(iv) 73 . 93 = 633

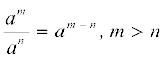

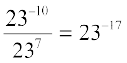

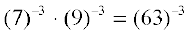

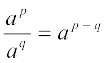

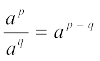

To get these answers, you would have used the following laws of exponents, which you have learnt in your earlier classes. (Here a, n and m are natural numbers. Remember, a is called the base and m and n are the exponents.)

(i) am . an = am + n (ii) (am)n = amn

(iii)  (iv) ambm = (ab)m

(iv) ambm = (ab)m

What is (a)0? Yes, it is 1! So you have learnt that (a)0 = 1. So, using (iii), we can get  We can now extend the laws to negative exponents too.

We can now extend the laws to negative exponents too.

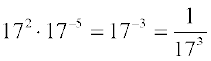

So, for example :

(i)  (ii)

(ii)

(iii)  (iv)

(iv)

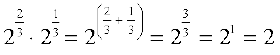

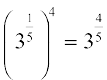

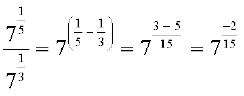

Suppose we want to do the following computations:

(i)  (ii)

(ii)

(iii)  (iv)

(iv)

How would we go about it? It turns out that we can extend the laws of exponents that we have studied earlier, even when the base is a positive real number and the exponents are rational numbers. (Later you will study that it can further to be extended when the exponents are real numbers.) But before we state these laws, and to even make sense of these laws, we need to first understand what, for example  is. So, we have some work to do!

is. So, we have some work to do!

In Section 1.4, we defined  for a real number a > 0 as follows:

for a real number a > 0 as follows:

Let a > 0 be a real number and n a positive integer. Then  = b, if bn = a and

= b, if bn = a and

b > 0.

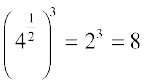

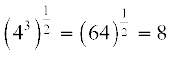

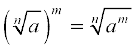

In the language of exponents, we define  =

=  . So, in particular,

. So, in particular,  . There are now two ways to look at

. There are now two ways to look at  .

.

=

=

=

=

Therefore, we have the following definition:

Let a > 0 be a real number. Let m and n be integers such that m and n have no common factors other than 1, and n > 0. Then,

=

=

We now have the following extended laws of exponents:

Let a > 0 be a real number and p and q be rational numbers. Then, we have

(i) ap . aq = ap+q (ii) (ap)q = apq

(iii)  (iv) apbp = (ab)p

(iv) apbp = (ab)p

You can now use these laws to answer the questions asked earlier.

Example 21 : Simplify (i)  (ii)

(ii)

(iii)  (iv)

(iv)

Solution :

(i)  (ii)

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

EXERCISE 1.6

1. Find : (i)  (ii)

(ii)  (iii)

(iii)

2. Find : (i)  (ii)

(ii)  (iii)

(iii)  (iv)

(iv)

3. Simplify : (i)  (ii)

(ii)  (iii)

(iii)  (iv)

(iv)

1.7 Summary

In this chapter, you have studied the following points:

1. A number r is called a rational number, if it can be written in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

2. A number s is called a irrational number, if it cannot be written in the form  , where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

3. The decimal expansion of a rational number is either terminating or non-terminating recurring. Moreover, a number whose decimal expansion is terminating or non-terminating recurring is rational.

4. The decimal expansion of an irrational number is non-terminating non-recurring. Moreover, a number whose decimal expansion is non-terminating non-recurring is irrational.

5. All the rational and irrational numbers make up the collection of real numbers.

6. There is a unique real number corresponding to every point on the number line. Also, corresponding to each real number, there is a unique point on the number line.

7. If r is rational and s is irrational, then r + s and r – s are irrational numbers, and rs and  are irrational numbers, r ≠ 0.

are irrational numbers, r ≠ 0.

8. For positive real numbers a and b, the following identities hold:

(i)  (ii)

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

(v)

9. To rationalise the denominator of  we multiply this by

we multiply this by  where a and b are integers.

where a and b are integers.

10. Let a > 0 be a real number and p and q be rational numbers. Then

(i) ap . aq = ap + q (ii) (ap)q = apq

(iii)  (iv) apbp = (ab)p

(iv) apbp = (ab)p