Table of Contents

Chapter 8

Quadrilaterals

8.1 Introduction

You have studied many properties of a triangle in Chapters 6 and 7 and you know that on joining three non-collinear points in pairs, the figure so obtained is a triangle. Now, let us mark four points and see what we obtain on joining them in pairs in some order.

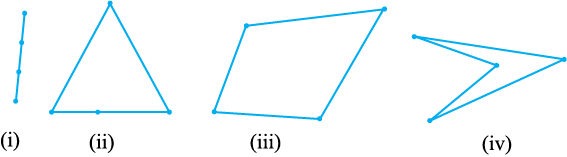

Fig. 8.1

Note that if all the points are collinear (in the same line), we obtain a line

segment [see Fig. 8.1 (i)], if three out of four points are collinear, we get a triangle

[see Fig. 8.1 (ii)], and if no three points out of four are collinear, we obtain a closed figure with four sides [see Fig. 8.1 (iii) and (iv)].

Such a figure formed by joining four points in an order is called a quadrilateral. In this book, we will consider only quadrilaterals of the type given in Fig. 8.1 (iii) but not as given in Fig. 8.1 (iv).

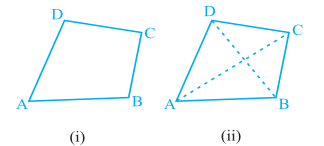

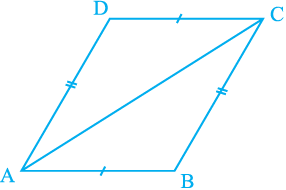

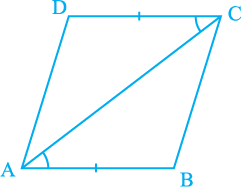

A quadrilateral has four sides, four angles and four vertices [see Fig. 8.2 (i)].

Fig. 8.2

In quadrilateral ABCD, AB, BC, CD and DA are the four sides; A, B, C and D are the four vertices and ∠ A, ∠ B, ∠ C and ∠ D are the four angles formed at the vertices.

Now join the opposite vertices A to C and B to D [see Fig. 8.2 (ii)].

AC and BD are the two diagonals of the quadrilateral ABCD.

In this chapter, we will study more about different types of quadrilaterals, their properties and especially those of parallelograms.

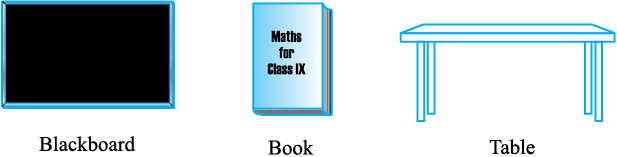

You may wonder why should we study about quadrilaterals (or parallelograms) Look around you and you will find so many objects which are of the shape of a quadrilateral - the floor, walls, ceiling, windows of your classroom, the blackboard, each face of the duster, each page of your book, the top of your study table etc. Some of these are given below (see Fig. 8.3).

Fig. 8.3

Although most of the objects we see around are of the shape of special quadrilateral called rectangle, we shall study more about quadrilaterals and especially parallelograms because a rectangle is also a parallelogram and all properties of a parallelogram are true for a rectangle as well.

8.2 Angle Sum Property of a Quadrilateral

Let us now recall the angle sum property of a quadrilateral.

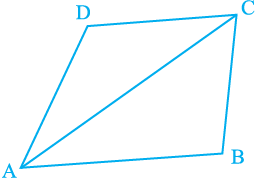

The sum of the angles of a quadrilateral is 360º. This can be verified by drawing a diagonal and dividing the quadrilateral into two triangles.

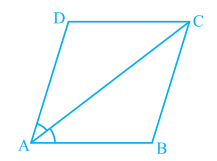

Let ABCD be a quadrilateral and AC be a diagonal (see Fig. 8.4).

Fig. 8.4

What is the sum of angles in ∆ ADC?

You know that

∠ DAC + ∠ ACD + ∠ D = 180° (1)

Similarly, in ∆ ABC,

∠ CAB + ∠ ACB + ∠ B = 180° (2)

Adding (1) and (2), we get

∠ DAC + ∠ ACD + ∠ D + ∠ CAB + ∠ ACB + ∠ B = 180° + 180° = 360°

Also, ∠ DAC + ∠ CAB = ∠ A and ∠ ACD + ∠ ACB = ∠ C

So, ∠ A + ∠ D + ∠ B + ∠ C = 360°.

i.e., the sum of the angles of a quadrilateral is 360°.

8.3 Types of Quadrilaterals

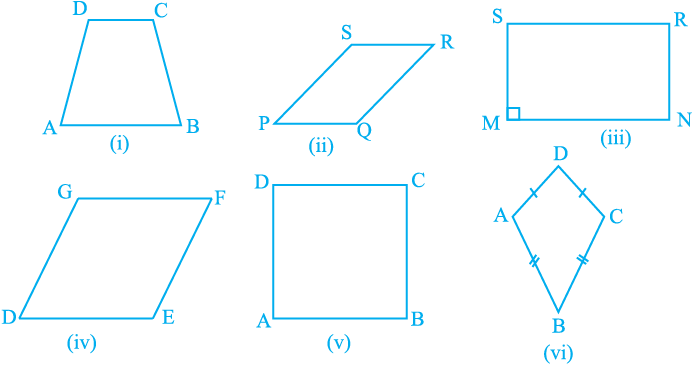

Look at the different quadrilaterals drawn below:

Fig. 8.5

Observe that :

- One pair of opposite sides of quadrilateral ABCD in Fig. 8.5 (i) namely, AB and CD are parallel. You know that it is called a trapezium.

- Both pairs of opposite sides of quadrilaterals given in Fig. 8.5 (ii), (iii) , (iv) and (v) are parallel. Recall that such quadrilaterals are called parallelograms.

So, quadrilateral PQRS of Fig. 8.5 (ii) is a parallelogram.

Similarly, all quadrilaterals given in Fig. 8.5 (iii), (iv) and (v) are parallelograms.

- In parallelogram MNRS of Fig. 8.5 (iii), note that one of its angles namely∠ M is a right angle. What is this special parallelogram called? Try to recall. It is called a rectangle.

- The parallelogram DEFG of Fig. 8.5 (iv) has all sides equal and we know that it is called a rhombus.

- The parallelogram ABCD of Fig. 8.5 (v) has ∠ A = 90° and all sides equal; it is called a square.

- In quadrilateral ABCD of Fig. 8.5 (vi), AD = CD and AB = CB i.e., two pairs of adjacent sides are equal. It is not a parallelogram. It is called a kite.

Note that a square, rectangle and rhombus are all parallelograms.

- A square is a rectangle and also a rhombus.

- A parallelogram is a trapezium.

- A kite is not a parallelogram.

- A trapezium is not a parallelogram (as only one pair of opposite sides is parallel in a trapezium and we require both pairs to be parallel in a parallelogram).

- A rectangle or a rhombus is not a square.

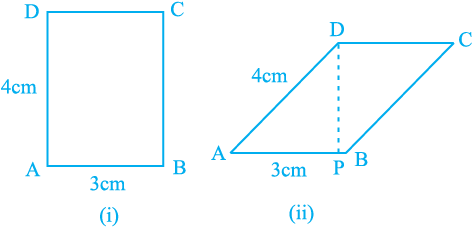

Look at the Fig. 8.6. We have a rectangle and a parallelogram with same perimeter 14 cm.

Fig. 8.6

Here the area of the parallelogram is DP × AB and this is less than the area of the rectangle, i.e., AB × AD as DP < AD. Generally sweet shopkeepers cut ‘Burfis’ in the shape of a parallelogram to accomodate more pieces in the same tray (see the shape of the Burfi before you eat it next time!).

Let us now review some properties of a parallelogram learnt in earlier classes.

8.4 Properties of a Parallelogram

Let us perform an activity.

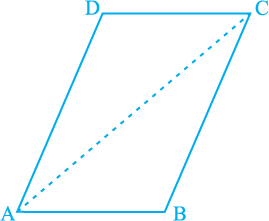

Cut out a parallelogram from a sheet of paper and cut it along a diagonal (see Fig. 8.7).You obtain two triangles. What can you say about these triangles?

Fig. 8.7

Place one triangle over the other. Turn one around, if necessary. What do you observe?

Observe that the two triangles are congruent to each other.

Repeat this activity with some more parallelograms. Each time you will observe that each diagonal divides the parallelogram into two congruent triangles.

Let us now prove this result.

Theorem 8.1 : A diagonal of a parallelogram divides it into two congruent triangles.

Proof : Let ABCD be a parallelogram and AC be a diagonal (see Fig. 8.8).

Fig. 8.8

Observe that the diagonal AC divides parallelogram ABCD into two triangles, namely, ∆ ABC and ∆ CDA. We need to prove that these triangles are congruent.

In ∆ ABC and ∆ CDA, note that BC || AD and AC is a transversal.

So, ∠ BCA = ∠ DAC (Pair of alternate angles)

Also, AB || DC and AC is a transversal.

So, ∠ BAC = ∠ DCA (Pair of alternate angles)

and AC = CA (Common)

So, ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ CDA (ASA rule)

or, diagonal AC divides parallelogram ABCD into two congruent

triangles ABC and CDA.

Now, measure the opposite sides of parallelogram ABCD. What do you observe?

You will find that AB = DC and AD = BC.

This is another property of a parallelogram stated below:

Theorem 8.2 : In a parallelogram, opposite sides are equal.

You have already proved that a diagonal divides the parallelogram into two congruent triangles; so what can you say about the corresponding parts say, the corresponding sides? They are equal.

So, AB = DC and AD = BC

Now what is the converse of this result? You already know that whatever is given in a theorem, the same is to be proved in the converse and whatever is proved in the theorem it is given in the converse. Thus, Theorem 8.2 can be stated as given below :

If a quadrilateral is a parallelogram, then each pair of its opposite sides is equal. So its converse is :

Theorem 8.3 : If each pair of opposite sides of a quadrilateral is equal, then it is a parallelogram.

Can you reason out why?

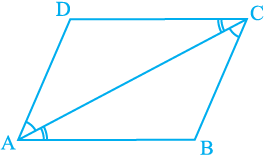

Let sides AB and CD of the quadrilateral ABCD be equal and also AD = BC (see Fig. 8.9).Draw diagonal AC.

Fig. 8.9

Clearly, ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ CDA (Why?)

So, ∠ BAC = ∠ DCA

and ∠ BCA = ∠ DAC (Why?)

Can you now say that ABCD is a parallelogram? Why?

You have just seen that in a parallelogram each pair of opposite sides is equal and conversely if each pair of opposite sides of a quadrilateral is equal, then it is a parallelogram. Can we conclude the same result for the pairs of opposite angles?

Draw a parallelogram and measure its angles. What do you observe?

Each pair of opposite angles is equal.

Repeat this with some more parallelograms. We arrive at yet another result as given below.

Theorem 8.4 : In a parallelogram, opposite angles are equal.

Now, is the converse of this result also true? Yes. Using the angle sum property of a quadrilateral and the results of parallel lines intersected by a transversal, we can see that the converse is also true. So, we have the following theorem :

Theorem 8.5 : If in a quadrilateral, each pair of opposite angles is equal, then it is a parallelogram.

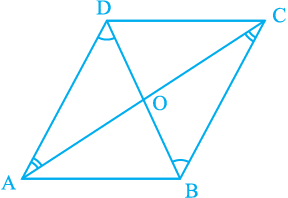

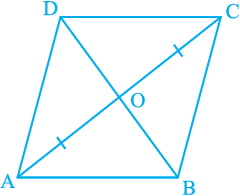

There is yet another property of a parallelogram. Let us study the same. Draw a parallelogram ABCD and draw both its diagonals intersecting at the point O

(see Fig. 8.10).

Measure the lengths of OA, OB, OC and OD.

What do you observe? You will observe that

OA = OC and OB = OD.

or, O is the mid-point of both the diagonals.

Repeat this activity with some more parallelograms.

Each time you will find that O is the mid-point of both the diagonals.

So, we have the following theorem :

Theorem 8.6 : The diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other.

Now, what would happen, if in a quadrilateral the diagonals bisect each other? Will it be a

parallelogram? Indeed this is true.

This result is the converse of the result of Theorem 8.6. It is given below:

Theorem 8.7 : If the diagonals of a quadrilateral bisect each other, then it is a parallelogram.

Fig. 8.10

You can reason out this result as follows:

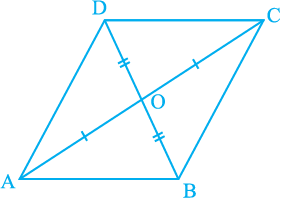

Note that in Fig. 8.11, it is given that OA = OC and OB = OD.

So, ∆ AOB ≅ ∆ COD (Why?)

Therefore, ∠ ABO = ∠ CDO (Why?)

From this, we get AB || CD

Similarly, BC || AD

Therefore ABCD is a parallelogram.

Let us now take some examples.

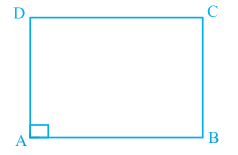

Example 1 : Show that each angle of a rectangle is a right angle.

Solution : Let us recall what a rectangle is.

Fig. 8.11

A rectangle is a parallelogram in which one angle is a right angle.

Let ABCD be a rectangle in which ∠ A = 90°.

We have to show that ∠ B = ∠ C = ∠ D = 90°

We have, AD || BC and AB is a transversal

(see Fig. 8.12).

Fig. 8.12

So, ∠ A + ∠ B = 180° (Interior angles on the same

ide of the transversal)

But, ∠ A = 90°

So, ∠ B = 180° – ∠ A = 180° – 90° = 90°

Now, ∠ C = ∠ A and ∠ D = ∠ B

(Opposite angles of the parallellogram)

So, ∠ C = 90° and ∠ D = 90°.

Therefore, each of the angles of a rectangle is a right angle.

Example 2 : Show that the diagonals of a rhombus are perpendicular to each other.

Solution : Consider the rhombus ABCD (see Fig. 8.13).

You know that AB = BC = CD = DA (Why?)

Now, in ∆ AOD and ∆ COD,

OA = OC (Diagonals of a parallelogram

bisect each other)

OD = OD (Common)

AD = CD

Therefore, ∆ AOD ≅ ∆ COD

(SSS congruence rule)

This gives, ∠ AOD = ∠ COD (CPCT)

But, ∠ AOD + ∠ COD = 180° (Linear pair)

So, 2∠ AOD = 180°

or, ∠ AOD = 90°

Fig. 8.13

So, the diagonals of a rhombus are perpendicular to each other.

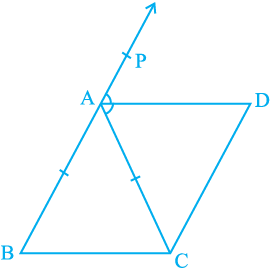

Example 3 : ABC is an isosceles triangle in which AB = AC. AD bisects exterior angle PAC and CD || AB (see Fig. 8.14). Show that

(i) ∠ DAC = ∠ BCA and (ii) ABCD is a parallelogram.

Solution : (i) ∆ ABC is isosceles in which AB = AC (Given)

So, ∠ ABC = ∠ ACB (Angles opposite to equal sides)

Also, ∠ PAC = ∠ ABC + ∠ ACB

(Exterior angle of a triangle)

or, ∠ PAC = 2∠ ACB (1)

Now, AD bisects ∠ PAC.

So, ∠ PAC = 2∠ DAC (2)

Therefore,

2∠ DAC = 2∠ ACB [From (1) and (2)]

or, ∠ DAC = ∠ ACB

Fig. 8.14

(ii) Now, these equal angles form a pair of alternate angles when line segments BC and AD are intersected by a transversal AC.

So, BC || AD

Also, BA || CD (Given)

Now, both pairs of opposite sides of quadrilateral ABCD are parallel.

So, ABCD is a parallelogram.

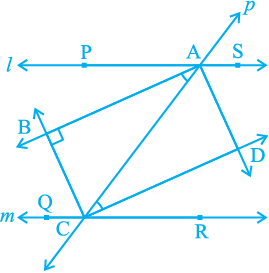

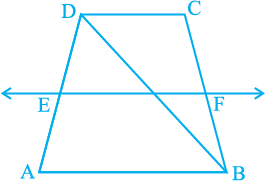

Example 4 : Two parallel lines l and m are intersected by a transversal p

(see Fig. 8.15). Show that the quadrilateral formed by the bisectors of interior angles is a rectangle.

Fig. 8.15

Solution : It is given that PS || QR and transversal p intersects them at points A and C respectively.

The bisectors of ∠ PAC and ∠ ACQ intersect at B and bisectors of ∠ ACR and

∠ SAC intersect at D.

We are to show that quadrilateral ABCD is a rectangle.

Now, ∠ PAC = ∠ ACR

(Alternate angles as l || m and p is a transversal)

So,  ∠ PAC =

∠ PAC =  ∠ACR

∠ACR

i.e., ∠ BAC = ∠ ACD

These form a pair of alternate angles for lines AB and DC with AC as transversal and they are equal also.

So, AB || DC

Similarly, BC || AD (Considering ∠ ACB and ∠ CAD)

Therefore, quadrilateral ABCD is a parallelogram.

Also, ∠ PAC + ∠ CAS = 180° (Linear pair)

So,  ∠ PAC +

∠ PAC + ∠ CAS =

∠ CAS =  × 180° = 90°

× 180° = 90°

or, ∠ BAC + ∠ CAD = 90°

or, ∠ BAD = 90°

So, ABCD is a parallelogram in which one angle is 90°.

Therefore, ABCD is a rectangle.

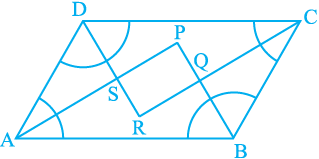

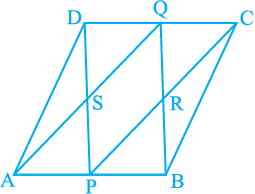

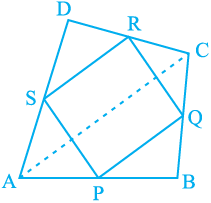

Example 5 : Show that the bisectors of angles of a parallelogram form a rectangle.

Solution : Let P, Q, R and S be the points of intersection of the bisectors of ∠ A and ∠ B, ∠ B and ∠ C, ∠ C and ∠ D, and ∠ D and ∠ A respectively of parallelogram ABCD (see Fig. 8.16).

Fig. 8.16

In ∆ ASD, what do you observe?

Since DS bisects ∠ D and AS bisects ∠ A, therefore,

∠ DAS + ∠ ADS =  ∠ A +

∠ A +  ∠ D

∠ D

=  (∠ A + ∠ D)

(∠ A + ∠ D)

=  × 180° (∠ A and ∠ D are interior angles on the same side of the transversal)

× 180° (∠ A and ∠ D are interior angles on the same side of the transversal)

= 90°

Also, ∠ DAS + ∠ ADS + ∠ DSA = 180° (Angle sum property of a triangle)

or, 90° + ∠ DSA = 180°

or, ∠ DSA = 90°

So, ∠ PSR = 90° (Being vertically opposite to ∠ DSA)

Similarly, it can be shown that ∠ APB = 90° or ∠ SPQ = 90° (as it was shown for

∠ DSA). Similarly, ∠ PQR = 90° and ∠ SRQ = 90°.

So, PQRS is a quadrilateral in which all angles are right angles.

Can we conclude that it is a rectangle? Let us examine. We have shown that

∠ PSR = ∠ PQR = 90° and ∠ SPQ = ∠ SRQ = 90°. So both pairs of opposite angles are equal.

Therefore, PQRS is a parallelogram in which one angle (in fact all angles) is 90° and so, PQRS is a rectangle.

8.5 Another Condition for a Quadrilateral to be a Parallelogram

You have studied many properties of a parallelogram in this chapter and you have also verified that if in a quadrilateral any one of those properties is satisfied, then it becomes a parallelogram.

We now study yet another condition which is the least required condition for a quadrilateral to be a parallelogram.

It is stated in the form of a theorem as given below:

Theorem 8.8 : A quadrilateral is a parallelogram if a pair of opposite sides is equal and parallel.

Fig. 8.17

Look at Fig 8.17 in which AB = CD and

AB || CD. Let us draw a diagonal AC. You can show that ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ CDA by SAS congruence rule.

So, BC || AD (Why?)

Let us now take an example to apply this property of a parallelogram.

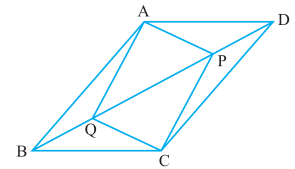

Example 6 : ABCD is a parallelogram in which P and Q are mid-points of opposite sides AB and CD(see Fig. 8.18).

Fig. 8.18

If AQ intersects DP at S and BQ intersects CP at R, show that:

(i) APCQ is a parallelogram.

(ii) DPBQ is a parallelogram.

(iii) PSQR is a parallelogram.

Solution : (i) In quadrilateral APCQ,

AP || QC (Since AB || CD) (1)

AP =  AB, CQ =

AB, CQ =  CD (Given)

CD (Given)

Also, AB = CD (Why?)

So, AP = QC (2)

Therefore, APCQ is a parallelogram [From (1) and (2) and Theorem 8.8]

(ii) Similarly, quadrilateral DPBQ is a parallelogram, because

DQ || PB and DQ = PB

(iii) In quadrilateral PSQR,

SP || QR (SP is a part of DP and QR is a part of QB)

Similarly, SQ || PR

So, PSQR is a parallelogram.

Exercise 8.1

1. The angles of quadrilateral are in the ratio 3 : 5 : 9 : 13. Find all the angles of the quadrilateral.

2. If the diagonals of a parallelogram are equal, then show that it is a rectangle.

3. Show that if the diagonals of a quadrilateral bisect each other at right angles, then it is a rhombus.

4. Show that the diagonals of a square are equal and bisect each other at right angles.

5. Show that if the diagonals of a quadrilateral are equal and bisect each other at right angles, then it is a square.

6. Diagonal AC of a parallelogram ABCD bisects

∠ A (see Fig. 8.19).Show that

Fig. 8.19

(i) it bisects ∠ C also,

(ii) ABCD is a rhombus.

7. ABCD is a rhombus. Show that diagonal AC bisects ∠ A as well as ∠ C and diagonal BD bisects ∠ B as well as ∠ D.

8. ABCD is a rectangle in which diagonal AC bisects ∠ A as well as ∠ C. Show that:

(i) ABCD is a square (ii) diagonal BD bisects ∠ B as well as ∠ D.

9. In parallelogram ABCD, two points P and Q are taken on diagonal BD such that DP = BQ (see Fig. 8.20). Show that:

Fig. 8.20

(i) ∆ APD ≅ ∆ CQB

(ii) AP = CQ

(iii) ∆ AQB ≅ ∆ CPD

(iv) AQ = CP

(v) APCQ is a parallelogram

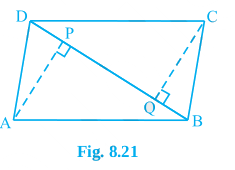

10. ABCD is a parallelogram and AP and CQ are perpendiculars from vertices A and C on diagonal BD (see Fig. 8.21). Show that

(i) ∆ APB ≅ ∆ CQD

(ii) AP = CQ

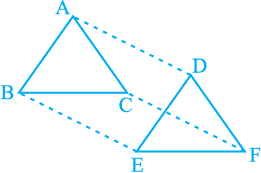

11. In ∆ ABC and ∆ DEF, AB = DE, AB || DE, BC = EF and BC || EF. Vertices A, B and C are joined to vertices D, E and F respectively (see Fig. 8.22). Show that

Fig. 8.22

(i) quadrilateral ABED is a parallelogram

(ii) quadrilateral BEFC is a parallelogram

(iii) AD || CF and AD = CF

(iv) quadrilateral ACFD is a parallelogram

(v) AC = DF

(vi) ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ DEF.

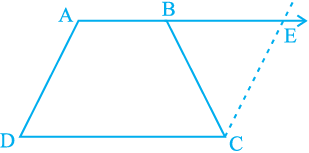

12. ABCD is a trapezium in which AB || CD and AD = BC (see Fig. 8.23). Show that

Fig. 8.23

(i) ∠ A = ∠ B

(ii) ∠ C = ∠ D

(iii) ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ BAD

(iv) diagonal AC = diagonal BD

[Hint : Extend AB and draw a line through C parallel to DA intersecting AB produced at E.]

8.6 The Mid-point Theorem

You have studied many properties of a triangle as well as a quadrilateral. Now let us study yet another result which is related to the mid-point of sides of a triangle. Perform the following activity.

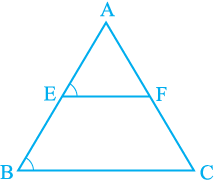

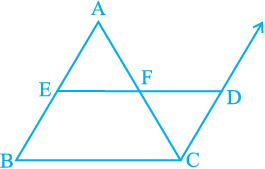

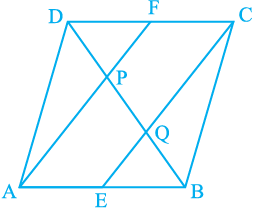

Draw a triangle and mark the mid-points E and F of two sides of the triangle. Join the points E and F (see Fig. 8.24).

Fig. 8.24

Measure EF and BC. Measure ∠ AEF and ∠ ABC.

What do you observe? You will find that :

EF =  BC and ∠ AEF = ∠ ABC

BC and ∠ AEF = ∠ ABC

so, EF || BC

Repeat this activity with some more triangles.

So, you arrive at the following theorem:

Theorem 8.9 : The line segment joining the mid-points of two sides of a triangle is parallel to the third side.

You can prove this theorem using the following clue:

Observe Fig 8.25 in which E and F are mid-points of AB and AC respectively and CD || BA.

Fig. 8.25

∆ AEF ≅ ∆ CDF (ASA Rule)

So, EF = DF and BE = AE = DC (Why?)

Therefore, BCDE is a parallelogram. (Why?)

This gives EF || BC.

In this case, also note that EF =  ED =

ED =  BC.

BC.

Can you state the converse of Theorem 8.9? Is the converse true?

You will see that converse of the above theorem is also true which is stated as below:

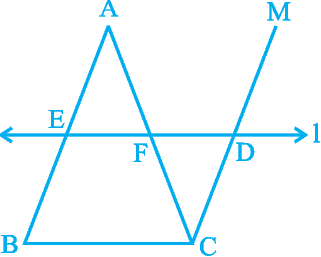

Theorem 8.10 : The line drawn through the mid-point of one side of a triangle, parallel to another side bisects the third side.

In Fig 8.26, observe that E is the mid-point of AB, line l is passsing through E and is parallel to BC and CM || BA.

Fig. 8.26

Prove that AF = CF by using the congruence of ∆ AEF and ∆ CDF.

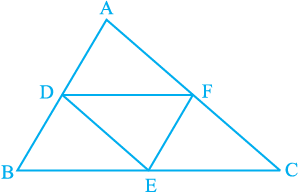

Example 7 : In ∆ ABC, D, E and F are respectively the mid-points of sides AB, BC and CA (see Fig. 8.27).

Fig. 8.27

Show that ∆ ABC is divided into four congruent triangles by joining D, E and F.

Solution : As D and E are mid-points of sides AB and BC of the triangle ABC, by Theorem 8.9,

DE || AC

Similarly, DF || BC and EF || AB

Therefore ADEF, BDFE and DFCE are all parallelograms.

Now DE is a diagonal of the parallelogram BDFE,

therefore, ∆ BDE ≅ ∆ FED

Similarly ∆ DAF ≅ ∆ FED

and ∆ EFC ≅ ∆ FED

So, all the four triangles are congruent.

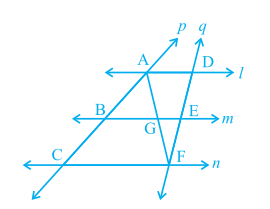

Example 8 : l, m and n are three parallel lines intersected by transversals p and q such that l, m and n cut off equal intercepts AB and BC on p (see Fig. 8.28). Show that l, m and n cut off equal intercepts DE and EF on q also.

Fig. 8.28

Solution : We are given that AB = BC and have to prove that DE = EF.

Let us join A to F intersecting m at G..

The trapezium ACFD is divided into two triangles; namely ∆ ACF and ∆ AFD.

In ∆ ACF, it is given that B is the mid-point of AC (AB = BC)

and BG || CF (since m || n).

So, G is the mid-point of AF (by using Theorem 8.10)

Now, in ∆ AFD, we can apply the same argument as G is the mid-point of AF,

GE || AD and so by Theorem 8.10, E is the mid-point of DF,

i.e., DE = EF.

In other words, l, m and n cut off equal intercepts on q also.

Exercise 8.2

1. ABCD is a quadrilateral in which P, Q, R and S are mid-points of the sides AB, BC, CD and DA

(see Fig 8.29). AC is a diagonal. Show that :

(i) SR || AC and SR =  AC

AC

(ii) PQ = SR

(iii) PQRS is a parallelogram.

Fig. 8.29

2. ABCD is a rhombus and P, Q, R and S are the mid-points of the sides AB, BC, CD and DA respectively. Show that the quadrilateral PQRS is a rectangle.

3. ABCD is a rectangle and P, Q, R and S are mid-points of the sides AB, BC, CD and DA respectively. Show that the quadrilateral PQRS is a rhombus.

4. ABCD is a trapezium in which AB || DC, BD is a diagonal and E is the mid-point of AD. A line is drawn through E parallel to AB intersecting BC at F (see Fig. 8.30). Show that F is the mid-point of BC.

Fig. 8.30

5. In a parallelogram ABCD, E and F are the mid-points of sides AB and CD respectively (see Fig. 8.31). Show that the line segments AF and EC trisect the diagonal BD.

6. Show that the line segments joining the mid-points of the opposite sides of a quadrilateral bisect each other.

7. ABC is a triangle right angled at C. A line through the mid-point M of hypotenuse AB and parallel to BC intersects AC at D. Show that

(i) D is the mid-point of AC (ii) MD ⊥ AC

(iii) CM = MA =  AB

AB

8.7 Summary

In this chapter, you have studied the following points :

1. Sum of the angles of a quadrilateral is 360°.

3. In a parallelogram,

(i) opposite sides are equal (ii) opposite angles are equal

(iii) diagonals bisect each other

4. A quadrilateral is a parallelogram, if

(i) opposite sides are equal or (ii) opposite angles are equal

or (iii) diagonals bisect each other

or (iv) a pair of opposite sides is equal and parallel

5. Diagonals of a rectangle bisect each other and are equal and vice-versa.

6. Diagonals of a rhombus bisect each other at right angles and vice-versa.

7. Diagonals of a square bisect each other at right angles and are equal, and vice-versa.

8. The line-segment joining the mid-points of any two sides of a triangle is parallel to the third side and is half of it.

9. A line through the mid-point of a side of a triangle parallel to another side bisects the third side.

10. The quadrilateral formed by joining the mid-points of the sides of a quadrilateral, in order, is a parallelogram.