Table of Contents

Chapter 9

Areas of Parallelograms and Triangles

9.1 Introduction

In Chapter 5, you have seen that the study of Geometry, originated with the measurement of earth (lands) in the process of recasting boundaries of the fields and dividing them into appropriate parts. For example, a farmer Budhia had a triangular field and she wanted to divide it equally among her two daughters and one son. Without actually calculating the area of the field, she just divided one side of the triangular field into three equal parts and joined the two points of division to the opposite vertex. In this way, the field was divided into three parts and she gave one part to each of her children. Do you think that all the three parts so obtained by her were, in fact, equal in area? To get answers to this type of questions and other related problems, there is a need to have a relook at areas of plane figures, which you have already studied in earlier classes.

You may recall that the part of the plane enclosed by a simple closed figure is called a planar region corresponding to that figure. The magnitude or measure of this planar region is called its area. This magnitude or measure is always expressed with the help of a number (in some unit) such as 5 cm2, 8 m2, 3 hectares etc. So, we can say that area of a figure is a number (in some unit) associated with the part of the plane enclosed by the figure.

We are also familiar with the concept of congruent figures from earlier classes and from Chapter 7. Two figures are called congruent, if they have the same shape and the same size.

Fig. 9.1

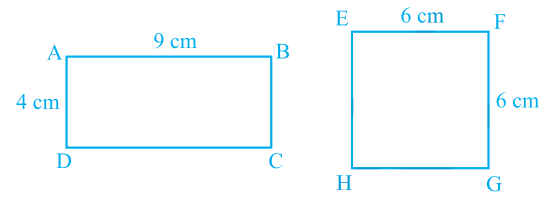

Fig. 9.2

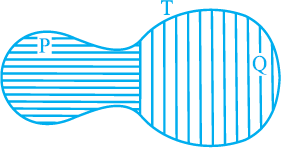

Now let us look at Fig. 9.3 given below:

Fig. 9.3

You may observe that planar region formed by figure T is made up of two planar regions formed by figures P and Q. You can easily see that

Area of figure T = Area of figure P + Area of figure Q.

You may denote the area of figure A as ar(A), area of figure B as ar(B), area of figure T as ar(T), and so on. Now you can say that area of a figure is a number

(in some unit) associated with the part of the plane enclosed by the figure with the following two properties:

(1) If A and B are two congruent figures, then ar(A) = ar(B);

and (2) if a planar region formed by a figure T is made up of two non-overlapping planar regions formed by figures P and Q, then ar(T) = ar(P) + ar(Q).

You are also aware of some formulae for finding the areas of different figures such as rectangle, square, parallelogram, triangle etc., from your earlier classes. In this chapter, attempt shall be made to consolidate the knowledge about these formulae by studying some relationship between the areas of these geometric figures under the condition when they lie on the same base and between the same parallels. This study will also be useful in the understanding of some results on ‘similarity of triangles’.

9.2 Figures on the Same Base and Between the Same Parallels

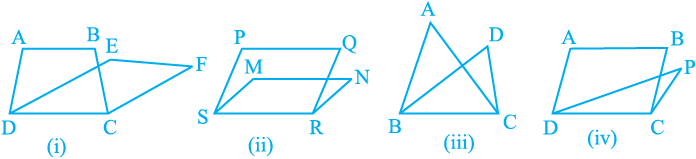

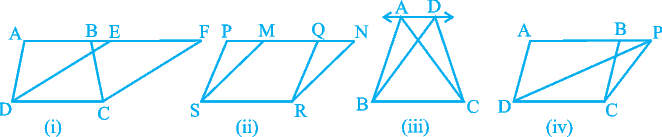

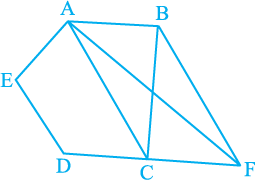

Look at the following figures:

Fig. 9.4

In Fig. 9.4(i), trapezium ABCD and parallelogram EFCD have a common side DC. We say that trapezium ABCD and parallelogram EFCD are on the same base DC. Similarly, in Fig. 9.4 (ii), parallelograms PQRS and MNRS are on the same base SR; in Fig. 9.4(iii), triangles ABC and DBC are on the same base BC and in

Fig. 9.4(iv), parallelogram ABCD and triangle PDC are on the same base DC.

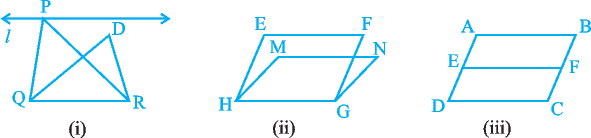

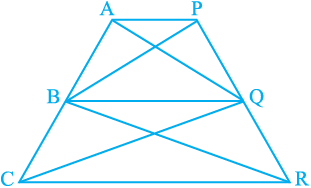

Now look at the following figures:

Fig. 9.5

In Fig. 9.5(i), clearly trapezium ABCD and parallelogram EFCD are on the same base DC. In addition to the above, the vertices A and B (of trapezium ABCD) opposite to base DC and the vertices E and F (of parallelogram EFCD) opposite to base DC lie on a line AF parallel to DC. We say that trapezium ABCD and parallelogram EFCD are on the same base DC and between the same parallels AF and DC. Similarly, parallelograms PQRS and MNRS are on the same base SR and between the same parallels PN and SR [see Fig.9.5 (ii)] as vertices P and Q of PQRS and vertices M and N of MNRS lie on a line PN parallel to base SR.In the same way, triangles ABC and DBC lie on the same base BC and between the same parallels AD and BC [see Fig. 9.5 (iii)] and parallelogram ABCD and triangle PCD lie on the same base DC and between the same parallels AP and DC [see Fig. 9.5(iv)].

So, two figures are said to be on the same base and between the same parallels, if they have a common base (side) and the vertices (or the vertex) opposite to the common base of each figure lie on a line parallel to the base.

Keeping in view the above statement, you cannot say that  PQR and

PQR and  DQR of Fig. 9.6(i) lie between the same parallels l and QR. Similarly, you cannot say that

DQR of Fig. 9.6(i) lie between the same parallels l and QR. Similarly, you cannot say that

Fig. 9.6

parallelograms EFGH and MNGH of Fig. 9.6(ii) lie between the same parallels EF and HG and that parallelograms ABCD and EFCD of Fig. 9.6(iii) lie between the same parallels AB and DC (even though they have a common base DC and lie between the parallels AD and BC). So, it should clearly be noted that out of the two parallels, one must be the line containing the common base.Note that ∆ABC and ∆DBE of Fig. 9.7(i) are not on the common base. Similarly, ∆ABC and parallelogram PQRS of Fig. 9.7(ii)are also not on the same base.

Fig. 9.7

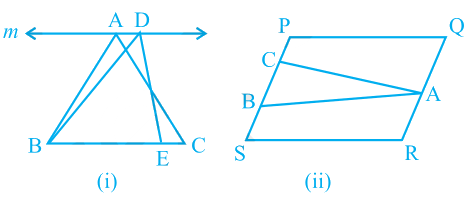

Exercise 9.1

1. Which of the following figures lie on the same base and between the same parallels. In such a case, write the common base and the two parallels.

Fig. 9.8

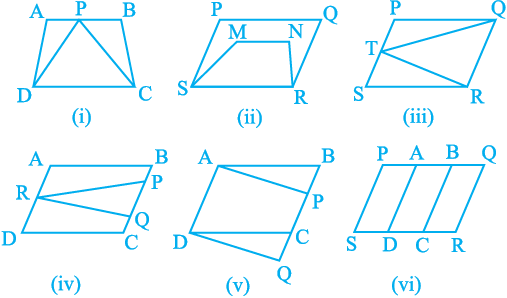

9.3 Parallelograms on the same Base and Between the same Parallels

Now let us try to find a relation, if any, between the areas of two parallelograms on the same base and between the same parallels. For this, let us perform the following activities:

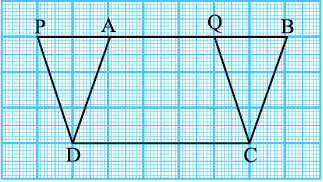

Activity 1 : Let us take a graph sheet and draw two parallelograms ABCD and PQCD on it as shown in Fig. 9.9.

Fig. 9.9

The above two parallelograms are on the same base DC and between the same parallels PB and DC. You may recall the method of finding the areas of these two parallelograms by counting the squares.

In this method, the area is found by counting the number of complete squares enclosed by the figure, the number of squares a having more than half their parts enclosed by the figure and the number of squares having half their parts enclosed by the figure. The squares whose less than half parts are enclosed by the figure are ignored. You will find that areas of both the parallelograms are (approximately) 15 cm2. Repeat this activity* by drawing some more pairs of parallelograms on the graph sheet. What do you observe? Are the areas of the two parallelograms different or equal? If fact, they are equal. So, this may lead you to conclude that parallelograms on the same base and between the same parallels are equal in area. However, remember that this is just a verification.

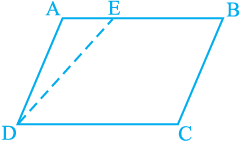

Activity 2 : Draw a parallelogram ABCD on a thick sheet of paper or on a cardboard sheet. Now, draw a line-segment DE as shown in Fig. 9.10.

Fig. 9.10

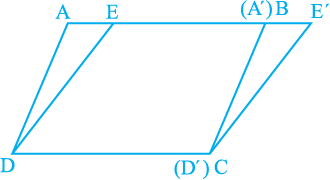

Next, cut a triangle A′ D′ E′ congruent to triangle ADE on a separate sheet with the help of a tracing paper and place A′ D′ E′ in such a way that A′ D′ coincides with BC as shown in Fig 9.11.Note that there are two parallelograms ABCD and EE′ CD on the same base DC and between the same parallels AE′ and DC. What can you say about their areas?

Fig. 9.11

As ∆ ADE ≅ ∆ A′ D′ E′

Therefore ar (ADE) = ar (A′ D′ E′ )

Also ar (ABCD) = ar (ADE) + ar (EBCD)

= ar (A′ D′ E′ ) + ar (EBCD)

= ar (EE′ CD)

So, the two parallelograms are equal in area.

Let us now try to prove this relation between the two such parallelograms.

*This activity can also be performed by using a Geoboard.

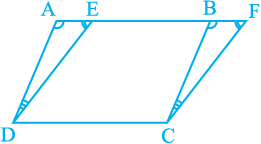

Theorem 9.1 : Parallelograms on the same base and between the same parallels are equal in area.

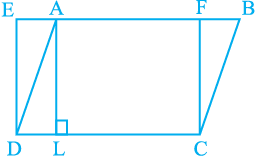

Proof : Two parallelograms ABCD and EFCD, on the same base DC and between the same parallels AF and DC are given (see Fig.9.12).

Fig. 9.12

We need to prove that ar (ABCD) = ar (EFCD).

In ∆ADE and ∆BCF,

∠ DAE =∠ CBF (Corresponding angles from AD || BC and transversal AF) (1)

∠ AED =∠ BFC (Corresponding angles from ED || FC and transversal AF) (2)

Therefore, ∠ ADE = ∠ BCF (Angle sum property of a triangle) (3)

Also, AD = BC (Opposite sides of the parallelogram ABCD) (4)

So, ∆ADE≅ ∆BCF [By ASA rule, using (1), (3), and (4)]

Therefore, ar (ADE) = ar (BCF) (Congruent figures have equal areas) (5)

Now, ar (ABCD) = ar (ADE) + ar (EDCB)

= ar (BCF) + ar (EDCB) [From(5)]

= ar (EFCD)

So, parallelograms ABCD and EFCD are equal in area.

Let us now take some examples to illustrate the use of the above theorem.

Example 1 : In Fig. 9.13, ABCD is a parallelogram and EFCD is a rectangle.

Also, AL  DC. Prove that

DC. Prove that

(i) ar (ABCD) = ar (EFCD)

(ii) ar (ABCD) = DC × AL

Fig. 9.13

Solution : (i) As a rectangle is also a parallelogram,

therefore, ar (ABCD) = ar (EFCD) (Theorem 9.1)

(ii) From above result,

ar (ABCD) = DC × FC (Area of the rectangle = length × breadth) (1)

As AL DC, therefore, AFCL is also a rectangle

DC, therefore, AFCL is also a rectangle

So, AL = FC (2)

Therefore, ar (ABCD) = DC × AL [From (1) and (2)]

Can you see from the Result (ii) above that area of a parallelogram is the product of its any side and the coresponding altitude. Do you remember that you have studied this formula for area of a parallelogram in Class VII. On the basis of this formula, Theorem 9.1 can be rewritten as parallelograms on the same base or equal bases and between the same parallels are equal in area.

Can you write the converse of the above statement? It is as follows: Parallelograms on the same base (or equal bases) and having equal areas lie between the same parallels. Is the converse true? Prove the converse using the formula for area of the parallelogram.

Example 2 : If a triangle and a parallelogram are on the same base and between the same parallels, then prove that the area of the triangle is equal to half the area of the parallelogram.

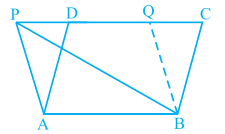

Solution : Let ∆ABP and parallelogram ABCD be on the same base AB and between the same parallels AB and PC (see Fig. 9.14).

Fig9.14

You wish to prove that ar (PAB) =  ar(ABCD)

ar(ABCD)

Draw BQ || AP to obtain another parallelogram ABQP. Now parallelograms ABQP and ABCD are on the same base AB and between the same parallels AB and PC.

Therefore, ar (ABQP) = ar (ABCD) (By Theorem 9.1) (1)

But PAB ≅ BQP (Diagonal PB divides parallelogram ABQP into two congruent triangles.)

So, ar (PAB) = (BQP) (2)

Therefore, ar (PAB) =  ar (ABQP) [From (2)] (3)

ar (ABQP) [From (2)] (3)

This gives ar (PAB) = ar(ABCD) [From (1) and (3)]

ar(ABCD) [From (1) and (3)]

ExerCise 9.2

1. In Fig. 9.15, ABCD is a parallelogram, AE  DC and CF

DC and CF  AD. If AB = 16 cm, AE = 8 cm and CF = 10 cm, find AD.

AD. If AB = 16 cm, AE = 8 cm and CF = 10 cm, find AD.

Fig. 9.15

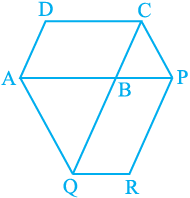

2. If E,F,G and H are respectively the mid-points of the sides of a parallelogram ABCD, show that

ar (EFGH) =  ar(ABCD).

ar(ABCD).

3. P and Q are any two points lying on the sides DC and AD respectively of a parallelogram ABCD. Show that ar (APB) = ar (BQC).

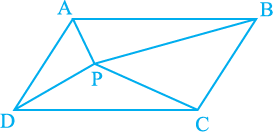

4. In Fig. 9.16, P is a point in the interior of a parallelogram ABCD. Show that

(i) ar (APB) + ar (PCD) =  ar(ABCD)

ar(ABCD)

(ii) ar (APD) + ar (PBC) = ar (APB) + ar (PCD)

[Hint : Through P, draw a line parallel to AB.]

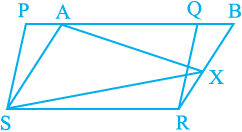

5. In Fig. 9.17, PQRS and ABRS are parallelograms and X is any point on side BR. Show that

Fig. 9.17

(i) ar (PQRS) = ar (ABRS)

(ii) ar (AX S) =  ar(PQRS)

ar(PQRS)

6. A farmer was having a field in the form of a parallelogram PQRS. She took any point A on RS and joined it to points P and Q. In how many parts the fields is divided? What are the shapes of these parts? The farmer wants to sow wheat and pulses in equal portions of the field separately. How should she do it?

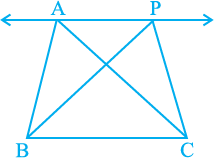

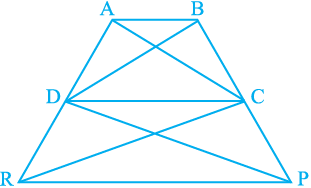

9.4 Triangles on the same Base and between the same Parallels

Let us look at Fig. 9.18. In it, you have two triangles ABC and PBC on the same base BC and between the same parallels BC and AP. What can you say about the areas of such triangles? To answer this question, you may perform the activity of drawing several pairs of triangles on the same base and between the same parallels on the graph sheet and find their areas by the method of counting the

squares. Each time, you will find that the areas of the two triangles are (approximately) equal. This activity can be performed using a geoboard also. You will again find that the two areas are (approximately) equal.

Fig. 9.18

To obtain a logical answer to the above question, you may proceed as follows:

In Fig. 9.18, draw CD || BA and CR || BP such that D and R lie on line AP(see Fig.9.19).

Fig. 9.19

From this, you obtain two parallelograms PBCR and ABCD on the same base BC and between the same parallels BC and AR.

Therefore, ar (ABCD) = ar (PBCR) (Why?)

Now ∆ABC ≅ ∆CDA and ∆PBC ∆ ≅ CRP (Why?)

So, ar (ABC) =  ar(ABCD)and ar (PBC) =

ar(ABCD)and ar (PBC) =  ar(PBCR) (Why?)

ar(PBCR) (Why?)

Therefore, ar (ABC) = ar (PBC)

In this way, you have arrived at the following theorem:

Theorem 9.2 : Two triangles on the same base (or equal bases) and between the same parallels are equal in area.

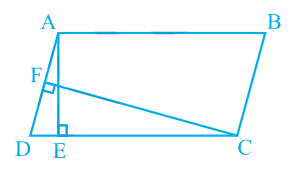

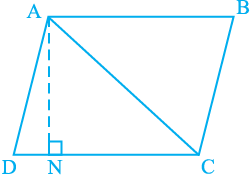

Now, suppose ABCD is a parallelogram whose one of the diagonals is AC

(see Fig. 9.20).Let AN | DC. Note that

Fig. 9.20

∆ADC ≅ ∆CBA (Why?)

So, ar (ADC) = ar (CBA) (Why?)

Therefore, ar (ADC) =  ar(ABCD)

ar(ABCD)

=  (DC x AN) (Why?)

(DC x AN) (Why?)

So, area of ∆ADC =  × base DC × corresponding altitude AN

× base DC × corresponding altitude AN

In other words, area of a triangle is half the product of its base (or any side) and the corresponding altitude (or height). Do you remember that you have learnt this formula for area of a triangle in Class VII ? From this formula, you can see that two triangles with same base (or equal bases) and equal areas will have equal corresponding altitudes.

For having equal corresponding altitudes, the triangles must lie between the same parallels. From this, you arrive at the following converse of Theorem 9.2 .

Theorem 9.3 : Two triangles having the same base (or equal bases) and equal areas lie between the same parallels.

Let us now take some examples to illustrate the use of the above results.

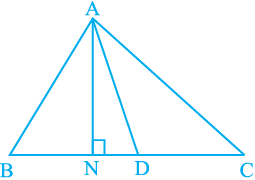

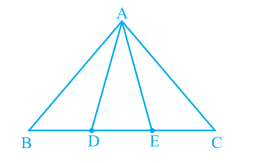

Example 3 : Show that a median of a triangle divides it into two triangles of equal areas.

Solution : Let ABC be a triangle and let AD be one of its medians (see Fig. 9.21).

Fig. 9.21

You wish to show that

ar (ABD) = ar (ACD).

Since the formula for area involves altitude, let us draw AN | BC.

Now ar(ABD) =  × base × altitude (of ∆ABD)

× base × altitude (of ∆ABD)

=  x BD xAN

x BD xAN

=  x CD x AN (As BD = CD)

x CD x AN (As BD = CD)

=  × base × altitude (of ∆ACD)

× base × altitude (of ∆ACD)

= ar(ACD)

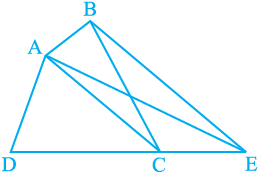

Example 4 : In Fig. 9.22, ABCD is a quadrilateral and BE || AC and also BE meets DC produced at E. Show that area of ∆ADE is equal to the area of the quadrilateral ABCD.

Fig. 9.22

Solution : Observe the figure carefully .

∆BAC and ∆EAC lie on the same base AC and between the same parallels AC and BE.

Therefore, ar(BAC) = ar(EAC) (By Theorem 9.2)

So, ar(BAC) + ar(ADC) = ar(EAC) + ar(ADC) (Adding same areas on both sides)

or ar(ABCD) = ar(ADE)

Exercise 9.3

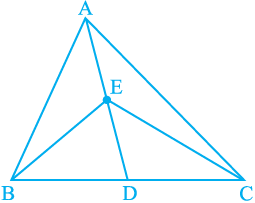

1. In Fig.9.23, E is any point on median AD of a ∆ABC. Show that ar (ABE) = ar (ACE).

Fig. 9.23

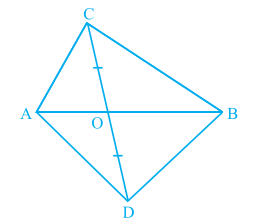

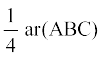

2. In a triangle ABC, E is the mid-point of median AD. Show that ar (BED) =  .

.

3. Show that the diagonals of a parallelogram divide it into four triangles of equal area.

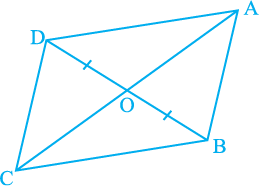

4. In Fig. 9.24, ABC and ABD are two triangles on the same base AB. If line- segment CD is bisected by AB at O, show that ar(ABC) = ar (ABD).

Fig. 9.24

5. D, E and F are respectively the mid-points of the sides BC, CA and AB of a ∆ABC. Show that

(i) BDEF is a parallelogram. (ii) ar (DEF) =

(iii) ar (BDEF) =  ar (ABC)

ar (ABC)

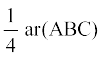

6. In Fig. 9.25, diagonals AC and BD of quadrilateral ABCD intersect at O such that OB = OD.

Fig. 9.25

If AB = CD, then show that:

(i) ar (DOC) = ar (AOB)

(ii) ar (DCB) = ar (ACB)

(iii) DA || CB or ABCD is a parallelogram.

[Hint : From D and B, draw perpendiculars to AC.]

7. D and E are points on sides AB and AC respectively of ∆ABC such that

ar (DBC) = ar (EBC). Prove that DE || BC.

8. XY is a line parallel to side BC of a triangle ABC. If BE || AC and CF || AB meet XY at E and F respectively, show that

ar (ABE) = ar (ACF)

9. The side AB of a parallelogram ABCD is produced to any point P. A line through A and parallel to CP meets CB produced at Q and then parallelogram PBQR is completed (see Fig. 9.26). Show that

ar (ABCD) = ar (PBQR).

Fig. 9.26

[Hint : Join AC and PQ. Now compare ar (ACQ) and ar (APQ).]

10. Diagonals AC and BD of a trapezium ABCD with AB || DC intersect each other at O. Prove that ar (AOD) = ar (BOC).

11. In Fig. 9.27, ABCDE is a pentagon. A line through B parallel to AC meets DC produced at F. Show that

(i) ar (ACB) = ar (ACF)

(ii) ar (AEDF) = ar (ABCDE)

Fig. 9.27

12. A villager Itwaari has a plot of land of the shape of a quadrilateral. The Gram Panchayat of the village decided to take over some portion of his plot from one of the corners to construct a Health Centre. Itwaari agrees to the above proposal with the condition that he should be given equal amount of land in lieu of his land adjoining his plot so as to form a triangular plot. Explain how this proposal will be implemented.

13. ABCD is a trapezium with AB || DC. A line parallel to AC intersects AB at X and BC

at Y. Prove that ar (ADX) = ar (ACY).

[Hint : Join CX.]

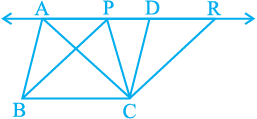

14. In Fig.9.28, AP || BQ || CR. Prove that

ar (AQC) = ar (PBR).

Fig. 9.28

15. Diagonals AC and BD of a quadrilateral ABCD intersect at O in such a way that

ar (AOD) = ar (BOC). Prove that ABCD is a trapezium.

16. In Fig.9.29, ar (DRC) = ar (DPC) and ar (BDP) = ar (ARC). Show that both the quadrilaterals ABCD and DCPR are trapeziums.

Exercise 9.4 (Optional)*

1. Parallelogram ABCD and rectangle ABEF are on the same base AB and have equal areas. Show that the perimeter of the parallelogram is greater than that of the rectangle.

2. In Fig. 9.30, D and E are two points on BC

such that BD = DE = EC. Show that

ar (ABD) = ar (ADE) = ar (AEC).

Fig. 9.30

Can you now answer the question that you have left in the ‘Introduction’ of this chapter, whether the field of Budhia has been actually divided into three parts of equal area?

[Remark: Note that by taking BD = DE = EC, the triangle ABC is divided into three triangles ABD, ADE and AEC of equal areas. In the same way, by dividing BC into n equal parts and joining the points of division so obtained to the opposite vertex of BC, you can divide ∆ABC into n triangles of equal areas.]

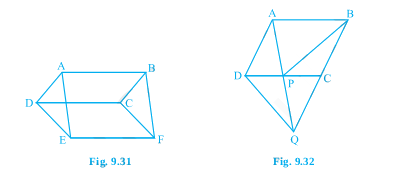

3. In Fig. 9.31, ABCD, DCFE and ABFE are parallelograms. Show that

ar (ADE) = ar (BCF).

4. In Fig. 9.32, ABCD is a parallelogram and BC is produced to a point Q such that

AD = CQ. If AQ intersect DC at P, show that ar (BPC) = ar (DPQ).

[Hint : Join AC.]

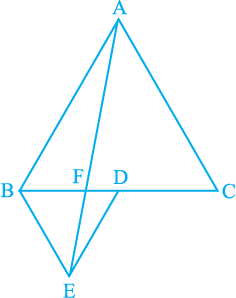

5. In Fig.9.33, ABC and BDE are two equilateral triangles such that D is the mid-point of BC. If AE intersects BC at F, show that

Fig. 9.33

(i) ar (BDE) =

(ii) ar (BDE) =  ar (BAE)

ar (BAE)

(iii) ar (ABC) = 2 ar (BEC)

(iv) ar (BFE) = ar (AFD)

(v) ar (BFE) = 2 ar (FED)

(vi) ar (FED) =  ar (AFC)

ar (AFC)

[Hint : Join EC and AD. Show that BE || AC and DE || AB, etc.]

6. Diagonals AC and BD of a quadrilateral ABCD intersect each other at P. Show that

ar (APB) × ar (CPD) = ar (APD) × ar (BPC).

[Hint : From A and C, draw perpendicular to BD.]

7. P and Q are respectively the mid-points of sides AB and BC of a triangle ABC and R is the mid-point of AP, show that

(i) ar (PRQ) =  ar (ARC) (ii) ar (RQC) =

ar (ARC) (ii) ar (RQC) =  ar (ABC)

ar (ABC)

(iii) ar (PBQ) = ar (ARC)

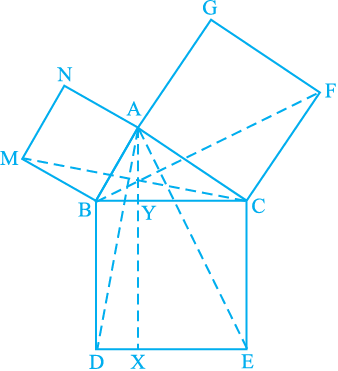

8. In Fig. 9.34, ABC is a right triangle right angled at A. BCED, ACFG and ABMN are squares on the sides BC, CA and AB respectively. Line segment AX DE meets BC at Y. Show that:

DE meets BC at Y. Show that:

Fig. 9.34

(i) ∆MBC ≅ ∆ABD (ii) ar (BYXD) = 2 ar (MBC)

(iii) ar (BYXD) = ar (ABMN) (iv) ∆FCB ≅ ∆ACE

(v) ar (CYXE) = 2 ar (FCB) (vi) ar (CYXE) = ar (ACFG)

(vii) ar (BCED) = ar (ABMN) + ar (ACFG)

Note : Result (vii) is the famous Theorem of Pythagoras. You shall learn a simpler proof of this theorem in Class X.

*These exercises are not from examination point of view.

9.5 Summary

In this chapter, you have studied the following points :

1. Area of a figure is a number (in some unit) associated with the part of the plane enclosed by that figure.

2. Two congruent figures have equal areas but the converse need not be true.

3. If a planar region formed by a figure T is made up of two non-overlapping planar regions formed by figures P and Q, then ar (T) = ar (P) + ar (Q), where ar (X) denotes the area of figure X.

4. Two figures are said to be on the same base and between the same parallels, if they have a common base (side) and the vertices, (or the vertex) opposite to the common base of each figure lie on a line parallel to the base.

5. Parallelograms on the same base (or equal bases) and between the same parallels are equal in area.

6. Area of a parallelogram is the product of its base and the corresponding altitude.

7. Parallelograms on the same base (or equal bases) and having equal areas lie between the same parallels.

8. If a parallelogram and a triangle are on the same base and between the same parallels, then area of the triangle is half the area of the parallelogram.

9. Triangles on the same base (or equal bases) and between the same parallels are equal in area.

10. Area of a triangle is half the product of its base and the corresponding altitude.

11. Triangles on the same base (or equal bases) and having equal areas lie between the same parallels.

12. A median of a triangle divides it into two triangles of equal areas.